Composition Forum 26, Fall 2012

http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/

Mapping the Questions: The State of Writing-Related Transfer Research

Abstract: The following article maps the questions, methods, contexts, and theories presented in published scholarship on writing-related transfer. While not exhaustive, this review attempts to capture representative samples with a focus on recent publications. The article then highlights a multi-institutional research initiative that aims to flesh out the field’s “map” and suggests additional areas for exploration.

Early maps of the American West were notoriously incomplete; while charting the rivers and pathways that had been explored, cartographers could only make (often incorrect) inferences about the (often vast) spaces in-between. Rivers that appeared to branch in one spot and rejoin each other in another might actually be completely different bodies of water; similarly, mountain cuts that seemed from a distance like viable paths through mountain ranges might reveal other barriers from different perspectives. As more people explored and claimed new uses for the land, maps gained more detail: territorial boundaries, tributaries to previously mapped rivers, viable routes through mountain ranges, section boundaries, railroad lines, and other markers of the three-dimensional details the maps attempted to represent. With new land survey methods, these maps became more comprehensive and better predictors of what subsequent explorers would find.

Like early maps of the American West, mapping the research on writing transfer reveals both pockets of detail and gaps in disciplinary knowledge. Even the pockets of detail often come with the limitations inherent in mapping; they typically reveal one moment in one “season” of a writing program, or the path of only a few students in their writing lives, or an assessment of a unique situation that might not be replicable at other institutions. Yet the growing amount of research exploring writing-related transfer does begin to offer a lay-of-the-land to understand where the discipline’s understanding of transfer is and where it might go.

What has rhetoric and composition asked about transfer, and what new questions might guide the field’s exploration of writing-related transfer? In the following pages, I map the questions, methods, contexts, and theories presented in published scholarship on writing-related transfer. While not exhaustive, this review attempts to capture representative samples with a focus on recent publications. I then highlight a multi-institutional research initiative that aims to flesh out the field’s “map” and suggest additional areas for exploration.

Existing Literature on Writing-Related Transfer

Although the title of this article suggests that the field has settled on “transfer” as the preferred term to describe applying knowledge or skills learned in one context to an alternate context, rhetoric and composition continues to use an array of terms, including transfer, transitions, integration, and generalizations. In part, the varied nomenclature stems both from the range of foundational theories borrowed from other disciplines and from rhetoric and composition’s early applications of those theories.

Borrowed Legends for Describing Transfer

Rhetoric and composition scholars studying transfer typically have borrowed from work by David N. Perkins and Gavriel Salomon, King Beach, Terttu Tuomi-Gröhn and Yrjö Engeström, Jan Meyer and Ray Land, or David Russell to provide a key or legend for discussing writing-related transfer. In Teaching for Transfer, Perkins and Salomon discuss the concepts of “high road” and “low road” transfer; low road transfer relies on a new context triggering practiced habits to facilitate transfer, while high road transfer requires “mindful abstraction” of knowledge from one context to another (25). Perkins and Salomon further distinguish between forward reaching and backward reaching high road transfer. In forward reaching, high road transfer, the learner considers how to apply the knowledge to future situations and alternate contexts, anticipating a future need; in backward reaching, high road transfer, the learner abstracts important characteristics of the current situation and looks to the past for relevant experiences and applicable knowledge.

Perkins and Salomon’s terms “near transfer” and “far transfer” also show up in writing-related transfer research. Near transfer refers to carrying knowledge or skill across similar contexts (their often cited example is driving a truck when you already have experience driving a car), while far transfer refers to carrying knowledge across different contexts (Teaching for Transfer 22). In the same article, the authors use “hugging” and “bridging” to label teaching activities that support low road and high road transfer, respectively.

Notably, Perkins and Salomon emphasize equipping learners with their own hugging and bridging strategies so that students can take an active role in their own learning and transfer of skills and knowledge. In Are Cognitive Skills Context-Bound? they extend this thread, emphasizing that transfer must be “cued, primed, and guided” (19), giving shape to their teacher as Good Shepard theory in a later piece (The Science and Art of Transfer).

Beach, in contrast, critiques the notion of transfer and instead examines generalization as knowledge propagation, suggesting that generalization is informed by social organization and acknowledges change by both the individual and the organization. Generalization as propagation further emphasizes associations across social organizations as active constructions, not just the application of knowledge to a new task. Beach extends his discussion by introducing the concept of consequential transition, which he explains as follows:

Transition, then, is the concept we use to understand how knowledge is generalized, or propagated, across social space and time. A transition is consequential when it is consciously reflected on, struggled with, and shifts the individual’s sense of self or social position. Thus, consequential transitions link identity with knowledge propagation. (42)

Several rhetoric and composition studies on writing-related transfer echo Beach’s emphasis on conscious reflection, even if they do not cite his work, suggesting that the field might benefit from revisiting his scholarship. To summarize here, though, Beach identifies four types of consequential transition: lateral, collateral, encompassing, and mediational. Lateral transition is a unidirectional movement from a preparatory activity to a related, developmentally advanced activity. Collateral transitions are multi-directional movements between concurrent activities, such as the daily transition from school to a part-time job. Encompassing transitions occur within social activities that are undergoing change and reflect adaptations to those transformations, and mediational transitions occur in simulations of future activities, mediating the participants’ developmental progress.

Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström summarize several conceptualizations of transfer, including Beach’s, comparing other theorists’ bases and modes of transfer and, in essence, providing a map of classical, cognitive, situated, sociocultural and activity-theory views of transfer that inform their own explorations of transfer. Their understanding of learning environments in which transfer can occur builds on activity theory; learners are intertwined with activity systems, and expansive learning occurs when learners question the existing practice of the collective activity. Briefly, testing and reflecting on new practices, and recruiting other participants to the redesigned process, leads to new activity systems. Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström advocate preparing learners to be boundary-crossers and change agents, exploring workplace activity systems and contributing to them.

Most recently, writing scholars have turned to the theory of threshold concepts to examine transfer. Jan Meyer and Ray Land describe threshold concepts as transformative; once students understand them, the concepts have the potential to transform how students identify with a discipline because the students begin to recognize the centrality of these concepts to the discipline. Threshold concepts are not simply key ideas, but rather the core of the disciplinary world view. Therefore until students grasp threshold concepts, these concepts could be barriers to transfer. Linda Adler-Kassner, John Majewski, and Damian Koshnick offer more discussion of threshold concepts in this issue.

While these are not the only theories of transfer that writing scholars pull across disciplinary borders, they are perhaps the most prominent, providing a shared key for labeling types of transfer and describing student journeys. Closer to home, scholars also draw from David Russell’s articulation of activity theory. Russell connects Vygotskian activity theory, as extended by Engeström and Aleksei Leont’ev, to genre theory, drawing from Charles Bazerman’s work. Russell describes school as an activity system with modified genres that are meaningful within that activity system but that do not adequately approximate the genres of professional activity systems. As students become more involved in a professional activity system, they begin to explore the system and its tools, including its genres, both learning more about the system and eventually reconceptualizing it in concert with other activity system members. Internships and other field experiences can facilitate this transition from school-based activity system to professional activity system, but Russell cautions that the movement is not anxiety-free or unproblematic. Students must reconfigure their identities as they straddle activity systems, including the activity systems beyond their disciplinary activity systems.

Individually and collectively, these pieces inform much of the recent scholarship on writing-related transfer. The following sections focus on that disciplinary research.

Questions about Writing-Related Transfer

While previous longitudinal studies touched on transfer, it was not their main theme, and rhetoric and composition research that focuses explicitly on writing-related transfer is still sparse. Nevertheless, some themes emerge from the limited studies.

Several studies (Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick; Beaufort; Bergmann and Zepernick; Clark and Hernandez; Driscoll; McCarthy; Nelms and Dively; Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey; Wardle Mutt Genres; and Wardle Understanding Transfer) focus on students’ transitions from first-year composition (FYC) to subsequent or concurrent contexts. Lucille McCarthy was one of the first to inquire about students’ writing experiences as they move from course to course. In Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC, Elizabeth Wardle asks, “What do students feel they learned and did in FYC? . . . Do students perceive FYC as helping them with later writing assignments across the university?” (70), questions Linda Bergmann and Janet Zepernick extend as they explore why students assume FYC knowledge will not transfer to writing in the disciplines. Dana Driscoll also pursues this line of questioning by asking how students’ perceptions of the applicability of FYC to writing in their majors change throughout FYC and the semester after they complete the course. Driscoll connects her inquiry to Perkins and Salomon’s work, asking how “concepts of forward reaching and backward reaching knowledge impact perceptions of writing transfer.” Nelms and Dively pursue a parallel question, exploring what writing-in-the-disciplines faculty think students have transferred to their classes from FYC.

Wardle (Understanding Transfer) and Anne Beaufort build on these questions about students’ perceptions by also asking about students’ subsequent writing experiences. Beaufort asks, “What knowledge domains—or mental schema—do writers need to invoke for analyzing new writing tasks in new discourse communities?” as she examines a student’s writing in FYC, two majors, and his first two years of post-graduation employment (17). Similarly, Liane Robertson, Kara Taczak, and Kathleen Blake Yancey (this issue) explore how students use prior knowledge in both FYC and a subsequent semester, and Wardle examines the writing that students do in classes beyond FYC in their first two years of college.

Yet writing-related transfer studies are not limited to FYC; other studies focus on students’ transitions to professional contexts. Chris Anson and Lee Forsberg investigate students’ transitions from academic to non-academic internship settings, and Nora Bacon inquires about students’ generalizations from writing in composition classes to writing for community-service agencies. Bacon’s questions highlight the complexity of examining these transitions:

What exactly is the relationship between the knowledge students develop in school and the knowledge they need in other settings? Do the skills and knowledge we value here have value in the community and the workplace as well? Do students learn them well enough to make use of them? Do they transfer automatically, or with effort, or not at all? (53)

Not only do teacher-scholars need to consider what knowledge is needed in each context, but they also must assess how that knowledge is valued. Once these (perhaps conflicting) priorities are addressed, scholars still face the question of how knowledge transfers—if it even does.

Other studies focus on genres in relation to transfer. Wardle’s ‘Mutt Genres’ and the Goal of FYC examines the “difficulties of teaching genres out of context” (767), while questioning whether general knowledge about genres will help students with writing for other courses. Irene Clark and Andrea Hernandez investigate whether a curriculum that helps students acquire genre awareness will enable them to make connections between FYC writing and writing in the disciplines. Rebecca Nowacek asks about students’ knowledge of genres and how they make use of prior knowledge when encountering new genres. Similarly, Angela Rounsaville (this issue) examines the role of uptake in students’ use of prior genre knowledge. While not focusing exclusively on transfer, Marilyn Sternglass asks a corresponding question about how feedback on previous assignments affects students’ future writing.

All of these questions are encompassed by questions about institutional structures. Nelms and Dively explicitly ask if the structure of educational experiences at their school facilitates transfer, Nowacek asks how “institutional structures affect student and instructor perceptions of transfer” (8), and Beaufort asks if universities could use their budgets more wisely than they currently do by investing in FYC. Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick (this issue) extend this line of questioning by prompting reflection on how the discipline’s expanding map of writing-related transfer and threshold concepts could inform institutional decisions about general education.

Disciplinary Methods for Studying Writing-Related Transfer

To explore these questions, writing-related transfer research includes both longitudinal studies (ranging from two to seven years) with a limited number of participants (ranging from one to nine focal students) and short-term studies (i.e., one or two semesters) with a greater number of participants. In both cases, the research tends to focus on a single institutional site, although student participants might be connecting with professionals in community organizations or workplaces. Rhetoric and composition researchers primarily work with student participants in writing-related transfer research, but most studies (e.g., Bacon, Beaufort, McCarthy, Nelms and Dively, Nowacek, Sternglass, and Wardle Mutt Genres) add the additional perspective of faculty or disciplinary experts through direct (e.g., interviews or surveys) and indirect (e.g., faculty comments) methods. Research methods with these and other participants include:

- Surveys of faculty (Nelms and Dively, Wardle Mutt Genres)

- Surveys of students (Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick; Clark and Hernandez; Driscoll; Nowacek; Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey; Sternglass; Wardle Mutt Genres; Wardle Understanding Transfer)

- Focus groups with faculty (Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick; Nelms and Dively; Wardle Mutt Genres)

- Focus groups with students (Bergmann and Zepernick, Nowacek, Wardle Mutt Genres, Wardle Understanding Transfer)

- Interviews with faculty (Bacon, Beaufort, McCarthy, Nowacek, Wardle Mutt Genres)

- Interviews with students (Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick; Anson and Forsberg; Bacon; Beaufort; Driscoll; McCarthy; Nowacek; Rounsaville; Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey; Sternglass; Wardle Understanding Transfer)

- Interviews with workplace or community organization supervisors (Bacon)

- Classroom observations (Bacon, Beaufort, McCarthy, Nowacek, Sternglass)

- Composing-aloud protocols (McCarthy)

Scholars analyze course materials, including group discussion logs (Anson and Forsberg), course journals (Anson and Forsberg), students’ class notes (Nowacek), student reflections (Anson and Forsberg, Bacon, Clark and Hernandez), and student writing samples (Anson and Forsberg; Bacon; Beaufort; McCarthy; Nowacek; Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey; Sternglass; Wardle Mutt Genres; Wardle Understanding Transfer). Beaufort, Nowacek, and Sternglass also examine faculty comments on students’ writing assignments.

The vast majority of writing-related transfer studies begin when student participants are first-year students, and they often focus on students who are taking or have recently completed a writing class, but some studies stray from this trend. Bergmann and Zepernick, for instance, intentionally sought “snapshots of students in various departments and years of study” (126). Similarly, Nowacek examined student writing in three linked courses in a single semester in an effort to add “detail-rich context” and “a thick synchronous slice of student life” (3). These snapshots and slices ultimately add detail to the writing-related transfer map, albeit in small sections.

Contexts of Writing-Related Transfer Studies

Most writing-related transfer studies have been conducted in the Midwest United States, often at research intensive institutions or mid-size schools with a heavy emphasis on science and technology. More recent studies have increased representation of the United States’ East Coast (e.g., Beaufort, Nowacek) and West Coast (e.g., Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick; Clark and Hernandez), and a few studies (e.g., Nowacek, Wardle Understanding Transfer) take place at private, Catholic institutions with emphases on liberal arts. While this geographic distribution does not necessarily reflect the geographical span of student participants’ hometowns or their educational backgrounds, it does highlight that, unlike some other foci of rhetoric and composition research, writing-related transfer research is not yet wide-spread. Further, this research—at least as cited in the field—has been confined within U.S. boundaries, with little, if any, carryover from other countries.

This context mapping additionally discloses that writing-related transfer research often occurs in the framework of other institutional initiatives. Wardle’s (Mutt Genres) participants are members of learning communities, as are the students in two sections of FYC included in Driscoll’s research. Nowacek’s participants are enrolled in linked courses, as are Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick’s students. Both Nowacek’s and Wardle’s (Understanding Transfer) students are members of honor programs. Bergmann and Zepernick situate their research within Writing Emphasized and Writing Intensive requirements, and Nelms and Dively were inspired to pursue their research based on their shared experiences on a Communication across the Curriculum task force. Anson and Forsberg study students’ transitions in writing internships, and Bacon focuses on a community service writing program. These contexts and initiatives might be inspiring more immediate questions about writing-related transfer, or program administrators in these contexts might be supporting transfer research as a way to learn about their courses/programs, but the field’s transfer publications rarely comment on these connections.

Research Outcomes and Writing-Related Transfer Theories

Unfortunately, reoccurring themes across many of these studies suggest that transfer is limited and students do not expect their writing in FYC, or even in classes in their majors, to transfer to other coursework or to professional contexts. Wardle (Mutt Genres), for instance, notes that transfer from FYC is complicated by “mutt genres” which “mimic genres that mediate activities in other activity systems, but within the FYC system their purposes and audiences are vague or even contradictory” (774). Without the authentic exigencies of these other activity systems, the genres cannot function realistically in FYC. Bacon provides a parallel outcome for upper-level writing classes. In her study of students transitioning to community service writing, students’ academic writing success often correlated with success in community writing, but school writing experiences could cause negative transfer if students were not rhetorically aware of the new context.

Bergmann and Zepernick suggest that students’ shared preconceptions about writing limit their generalizations of writing knowledge and strategies. Like Dave in McCarthy’s study, Bergmann and Zepernick’s participants interpreted writing for the disciplines as different from writing for FYC. They found that students view writing in English classes “as personal and expressive rather than academic or professional” so they question the relevance of strategies they learn in English writing classes to other disciplinary contexts (129). Students were more likely to accept disciplinary conventions in writing and to identify writing strategies as generalizable if they learned the strategies in writing in the disciplines (WID) courses. Bergmann and Zepernick emphasize, “The attitudes expressed by our respondents suggest that the primary obstacle to such transfer is not that students are unable to recognize situations outside FYC in which those skills can be used, but that students do not look for situations because they believe that skills learned in FYC have no value in any other setting” (139). Driscoll’s results echo this sentiment, as her student participants became less optimistic about the transferability of FYC material as the semester progressed. Driscoll identifies four categories of student perceptions of transfer: “explicitly connected, implicitly connected, uncertain, and disconnected.” Students in the “explicitly connected” category articulate connections between FYC and their future writing, while students in the “implicitly connected” category articulate only general values of what they are learning. Nearly half of Driscoll’s participants, though, fall in the “disconnected” or “uncertain” categories, which Driscoll hypothesizes is an outcome of the lack of connection students see between FYC and disciplinary writing. “Disconnected” students see no writing in their futures or anticipate no usefulness of what they are learning to their futures.

Clark and Hernandez offer a slight counter-point to Driscoll’s results, although their smaller sample size limits generalization. The students they surveyed continued to value the five-paragraph essay (which was not a focus of the FYC class) and the academic argument essay (a course assignment), and at the end of the semester, students indicated that their understanding of genre made them less anxious about writing. In essence, students’ experiences in FYC probably did not change their valuation of genre. Clark and Hernandez share student reflections that suggest other individual takeaways from the course, though, and FYC may have lessened students’ writing anxiety. Given their results, Clark and Hernandez propose that genre awareness might be a threshold concept (see Meyer, Land, and Baillie) that students need to master to facilitate transfer to writing in the disciplines.

Genre knowledge alone is not sufficient, though, according to Beaufort. She uses her longitudinal study results to illustrate the need for five overlapping knowledge domains: writing process knowledge, subject matter knowledge, rhetorical knowledge, and genre knowledge, all of which are encompassed by the fifth domain, discourse community knowledge (18-19). Beaufort concludes that identifying and reflecting on discourse communities is necessary for positive transfer. Since students are novices moving among multiple discourse communities during their academic studies, they need university-wide, sequenced instruction of socially-situated writing conventions.

Nelms and Dively suggest that students are not the only ones questioning transfer from FYC to the disciplines. Writing Intensive faculty in their study expressed concern about lack of transfer, even though some strategies (understanding of thesis and support, text analysis, citation) did transfer. Like the Cell Biology professor in McCarthy’s study, faculty indicated that they have limited time for writing assignments and writing instruction in their content courses, and they perceive a lack of student motivation regarding writing. These responses highlight the challenges of achieving Beaufort’s desired university-wide instruction. Plus, Nelms and Dively note that instructors in FYC used different terminology than faculty in writing in the discipline classes. Even when instructors identify threshold concepts that could transfer between linked classes, Adler-Kassner, Majewski, and Koshnick found that instructors might not make their own transition to a postliminal stage of teaching the threshold concepts they they’ve identified. Collectively, these results suggest a lack of Perkins and Salomon’s desired “bridging” or Beaufort’s hoped-for explicit sequencing of writing conventions instruction.

Perhaps because of faculty’s perception that they cannot make time for writing, Wardle’s (Understanding Transfer) participants came across minimal need beyond FYC for writing knowledge and strategies in their first two years of college; when they were assigned writing projects, students typically encountered summary tasks that required minimal research. As a result, the school activity system was not prompting generalization or transfer, and rare instances of generalization were not conscious, instead identified after subsequent reflection.

Similarly, when students in Nowacek’s study applied knowledge or strategies from one linked course to another, faculty often did not recognize the attempt at transfer, leaving students to sort through why some knowledge and strategies could cross courses and others could not. As in Nelms and Dively’s study, different terminology—or different disciplinary understandings of the same term—sometimes compromised transfer. Yet when faculty discussions highlighted disciplinary differences during co-taught portions of the linked courses in Nowacek’s study, the experience was jarring for students, particularly if they identified the exchanges as interruptions by one faculty member rather than as a dialogue among the faculty. Since the vast majority of Nowacek’s participants were first-year students, they might not be developmentally ready to navigate both the subject matter differences and the genre knowledge differences among the three discourse communities represented in their linked courses, again reiterating the potential value of Beaufort’s call for sequenced instruction.

Nevertheless, several studies do offer a degree of optimism centered around “bridging” structures and instruction. Nelms and Dively, for instance, speculate that reflection inherent in other studies might have facilitated transfer that otherwise would not have happened. In Wardle’s Understanding Transfer study, the exception to students’ dearth of opportunities for transfer was meta-awareness about writing. Consistent with this finding, Wardle (Mutt Genres) advocates shifting gears with FYC and exploring the impact of a writing about writing curriculum that would increase students’ meta-awareness.

Anson and Forsberg suggest that students’ transitions to professional writing follow a developmental path with stages of expectation, disorientation and struggle, and finally, transition and resolution. This path illustrates the messiness that Russell describes when he discusses students’ experiences moving between activity systems. Students’ success with this developmental transition depends on their ability to acquire strategies for adapting, also emphasizing the importance of students taking an active role in “bridging,” as Perkin and Salomon suggest.

Nowacek offers a theory for understanding how students might take this ownership of their own transfer. As “agents of integration,” students “perceive as well as … convey effectively to others connections between previously distinct contexts” (38, emphases in original). The theory’s emphasis on students refocuses attention on the agents in the activity system and on students’ ability to reshape the activity system. Nowacek also uses the term integration to distinguish between unconscious transfer and intentional, meta-aware transfer (i.e., integration), emphasizing the importance for some types of transfer (e.g., high road transfer) of the meta-awareness Wardle discusses, even while acknowledging that meta-awareness is not necessary for all instances of transfer.

Finally, building on genre theory, Nowacek situates students as agents of integration within a theory of transfer as recontextualization, which she unpacks with five principles. She suggests that transfer as recontextualization recognizes that:

- “multiple avenues of connection [exist] among contexts, including knowledge, ways of knowing, identities, and goals” (21),

- “transfer is not only mere application; it is also an act of reconstruction” (25),

- “transfer can be both positive and negative and … there is a powerful affective dimension of transfer” (26),

- “written and spoken genres associated with these contexts provide an exigence for transfer” (28), and

- “meta-awareness is an important, but not a necessary, element of transfer” (30).

Echoes of Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström’s and Russell’s conceptualizations of activity theory run through these principles, as transfer becomes a means of reshaping complex activity systems and as recontextualization acknowledges that students often inhabit multiple – and sometimes conflicting—activity systems. Further, within this matrix of types of transfer, Nowacek keeps the student as agent – as central to and the center of explorations of integration.

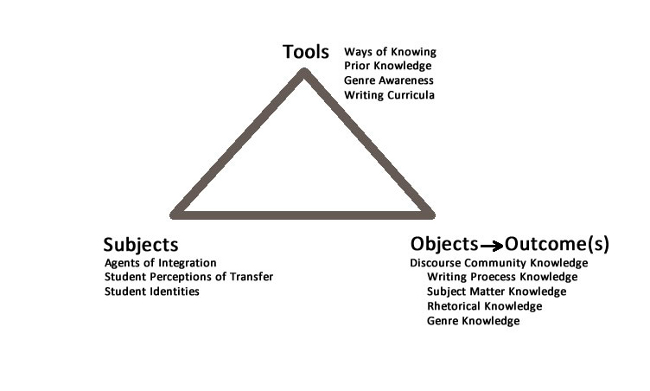

Collectively, then, these studies of writing-related transfer suggest a growing emphasis on examining the complexity of transfer through the lens of activity systems, with the result of different studies adding knowledge to different portions of an activity system map. In Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis, Russell offers a visual representation of an activity system, labeling the tip of a triangle as “Mediational Means (Tools)” and the base angles as “Subject(s)” and “Object/Motive Outcome(s)” (5). Although Figure 1 admittedly is oversimplified, it borrows these labels to illustrate the ways in which the transfer studies have focused on varied aspects of writing-related transfer as activity.

Figure 1. Foci of Writing-Related Transfer Research

Several shorter-term studies add depth to our understanding of student perceptions of transfer (e.g., Bergmann and Zepernick), lending insight to the subjects in the activity system. Others focus on writing curricula (e.g., Robertson, Taczak, and Yancey) or to students’ genre awareness (e.g., Clark), highlighting tools in the activity system. Many suggest desired outcomes, like discourse community knowledge (e.g., Beaufort), that would facilitate transfer between activity systems. Longitudinal studies often flesh out more than one area, but with fewer participants. Therefore, we learn that Nowacek’s focus students attempted to use prior knowledge as a tool to advance their positioning within a discourse community. Similarly, Wardle (Understanding Transfer) examines both students’ perceptions and their use (or non-use) of tools like prior writing process knowledge. Of course, what complicates the representation above is that once students acquire specific types of knowledge as an achieved outcome, they can reshape the activity system—or move to another activity system—and use that now prior knowledge as a tool for achieving new outcomes. Thus discourse community knowledge, an outcome of participation in one activity system, could shift to prior knowledge, a tool in the new or reshaped activity system.

This mapping of the existing research is not comprehensive, but it is intended to offer a lay of the land as scholars move forward with research on writing-related transfer. It also draws attention to the limits of our disciplinary knowledge on transfer and emphasizes the need for continued research. For instance, while some scholars (i.e., Beaufort, Nelms and Dively, and Nowacek) explicitly question the structure of the holistic, educational activity system (e.g., FYC as a university requirement or the institutional structures that promote or inhibit writing transfer), none of these studies are able to examine the holistic system; to do so even with a focus on only one subject would be daunting because researchers cannot observe their subjects in every class, every study session, and every peripheral activity system (i.e., extracurricular activities, social activities, work activities, etc.). Yet scholars can continue to add detail to sections of the map by: studying writing-related transfer at other types of institutions and in other geographic regions; recruiting student participants with underrepresented identities; continuing to examine the tools students use for transfer and integration; examining the overlapping, intersecting, and disparate activity systems that students move among; and (re)examining students’ intended goals and outcomes. Some of this detail already is being added via projects conducted through the Elon Research Seminar on Critical Transitions.

Extending Writing-Related Transfer Research Through the Elon Research Seminar

In an effort to flesh out more of this writing-related transfer mapping, the Elon University and AAC&U Research Seminar on Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer{1} supports campus-based and multi-institutional research addressing and surrounding this theme over a two-year period. Forty participants from five countries and over 20 institutions are gathering for two one-week summer meetings on the Elon University campus, as well as a culminating conference in the third summer.

Working with multi-institutional teams formed by seminar leaders (Chris Anson of North Carolina State University, Randy Bass of Georgetown University, and this author of Elon University) and adjusted by participants early in the seminar, scholars met in June 2011 to develop and plan research projects to be conducted throughout the following year at the participants’ own institutions. Participants have reconvened in June 2012 to share their initial results and to plan more sharply focused research agendas for their research cohorts for year two. These research cohorts afford inter-institutional collaborations that enable larger scale studies and explorations of the impact of different institutional contexts. Finally, in summer 2013, participants will reconvene to share their year two results, to plan continuations of their work, and to host a conference on writing-related transfer.

The Elon Research Seminar’s large application pool and 22% acceptance rate emphasize the growing interest in understanding writing-related transfer. Likewise, the interdisciplinarity of several of the cohorts reflects a desire to cross disciplinary boundaries as these scholars learn more about writing across critical transitions. Some cohort members have disciplinary homes in foreign languages, sociology, and geography and environmental studies, to identify just a few of the cross-disciplinary connections supported by the research seminar.

Although the ERS cohorts are only in the first year of their collaborations, their research foci already hint at the ways these projects will deepen the disciplines’ understanding of transfer. ERS cohorts are concentrating on writing-related transfer across eight critical transitions: first-year writing to general education, first-year writing to other upper-level writing, general education to the major, high school to college, college to workplace, first language to second language, writing about writing to real-life contexts, and informal to formal learning spaces (and vice versa). Within these areas, researchers are examining the effect of using specific tools, including technologies, writing about writing curricula, and prior knowledge from writing in another language. Others are examining what students carryover from informal activity systems to more formal academic activity systems and how faculty can facilitate metacognitive reflection to promote integration (or conscious transfer).{2} Furthermore, the participant pool pushes the geographic boundaries of writing-related transfer research, bridging studies throughout the United States with studies in Denmark, South Africa, Ireland, and Australia.

Adding Detail and Exploring Uncharted Areas

Even with the work of these multi-institutional ERS teams, the map of writing-related transfer research has vast areas of uncharted territory. Existing studies primarily focus on academic contexts, overlooking students’ many non-academic activity systems. How do complementary, parallel, and intersecting activity systems impact students’ shifts among concurrent activity systems, as well as from school to professional activity systems? Do students have access to other tools acquired in other activity systems that faculty should encourage students to access to facilitate transfer in the academic activity system?

While several longitudinal studies referenced above begin to explore other disciplinary sub-systems of students’ educational experience, rhetoric and composition scholars need to engage in more boundary-crossing just as Tuomi-Gröhn and Engeström advocate for learners. Collaborations with other disciplines could result in deeper exploration of how students’ movement among different school activity systems impacts their self-identity and tool appropriation in each. Can teachers integrate more bridges and transitional strategies if they know more about the other disciplines and discourse communities students encounter? Is it possible to answer Beaufort’s call for university-wide, sequenced instruction of socially-situated writing conventions? Beyond addressing these questions, boundary-crossing also might introduce new research methods.

Finally, even in the Elon Research Seminar, research-intensive universities play a dominant role as cartographers of writing-related transfer maps. How do institutional characteristics shape activity systems? To test the validity of the disciplinary mapping of writing-related transfer, scholars will need to replicate it with other “travelers” from other institution types, geographic regions, and identity groups. While not always as highly valued as explorations into uncharted lands, these types of replications will improve the validity of the mapping and ultimately make disciplinary and curricular responses to the collective research more meaningful.

Notes

- Visit http://www.elon.edu/e-web/academics/teaching/ers/writing_transfer/ to learn more about the Elon Research Seminar on Writing Transfer. (Return to text.)

- When scholarship related to these studies is published, it will be inventoried on the Elon Research Seminar website. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Adler-Kassner, Linda, John Majewski, and Damian Koshnick. The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum 26 (2012). Web.

Anson, Chris M., and L. Lee Forsberg. Moving Beyond the Academic Community: Transitional Stages in Professional Writing. Written Communication 7.2 (1990): 200-31. Print.

Bacon, Nora. The Trouble with Transfer: Lessons from a Study of Community Service Writing. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning 6 (1999): 53-62. Print.

Beach, King. Consequential Transitions: A Developmental View of Knowledge Propagation Through Social Organizations. Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-crossing. Ed. Terttu Tuomi-Gröhn and Yrjö Engeström. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group, 2003. 39-61. Print.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, 2007. Print.

Bergmann, Linda S, and Janet Zepernick. Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students’ Perceptions of Learning to Write. Writing Program Administration 31.1-2 (2007): 124-49. Print.

Clark, Irene L., and Andrea Hernandez. Genre Awareness, Academic Argument, and Transferability. The WAC Journal 22 (2011). Web. 15 January 2012. <http://wac.colostate.edu/journal/vol22/clark.pdf>.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn. Connected, Disconnected, or Uncertain: Student Attitudes about Future Writing Contexts and Perceptions of Transfer from First Year Writing to the Disciplines. Across the Disciplines 8.2 (2011). Web. 15 January 2012. <http://wac.colostate.edu/atd/articles/driscoll2011/index.cfm>.

McCarthy, Lucille Parkinson. A Stranger in Strange Lands: A College Student Writing across the Curriculum. Research in the Teaching of English 21.3 (1987): 233-65. Print.

Meyer, Jan H. F., and Ray Land. Introduction. Overcoming Barriers to Student Understanding: Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge. Ed. Jan H. F. Meyer and Ray Land. London: Routledge, 2006. 3-18. Print.

Meyer, Jan H. F., Ray Land, and Caroline Baillie, eds. Threshold Concepts and Transformation Learning. Rotterdam, the Netherlands: Sense, 2010. Print.

Nelms, Gerald, and Ronda Leathers Dively. Perceived Roadblocks to Transferring Knowledge from First-Year Composition to Writing-Intensive Major Courses: A Pilot Study. Writing Program Administration 31.1-2 (2007): 214-40. Print.

Nowacek, Rebecca S. Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois UP, 2011. Print.

Perkins, David N., and Gavriel Salomon. Are Cognitive Skills Context-Bound? Educational Researcher 18.1 (1989): 16-25. Print.

---. Teaching for Transfer. Educational Leadership 46.1 (1988): 22-32. Print.

---. The Science and Art of Transfer. Web. 15 January 2012. <http://learnweb.harvard.edu/alps/thinking/docs/trancost.htm>.

Robertson, Liane, Kara Taczak, and Kathleen Blake Yancey. A Theory of Prior Knowledge and Its Role in College Composers’ Transfer of Knowledge and Practice. Composition Forum 26 (2012). Web.

Rounsaville, Angela. Selecting Genres for Transfer: The Role of Uptake in Students’ Antecedent Genre Knowledge. Composition Forum 26 (2012). Web.

Russell, David. Rethinking Genre in School and Society: An Activity Theory Analysis. Written Communication 14.4 (1997): 504-54. Print.

Sternglass, Marilyn S. Time to Know Them: A Longitudinal Study of Writing and Learning at the College Level. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1997. Print.

Tuomi-Gröhn, Terttu, and Yrjö Engeström. Conceptualizing Transfer: From Standard Notions to Developmental Perspectives. Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-crossing. Ed. Terttu Tuomi-Gröhn and Yrjö Engeström. Bingley, UK: Emerald Group, 2003. 19-38. Print.

Wardle, Elizabeth. ‘Mutt Genres’ and the Goal of FYC: Can We Help Students Write the Genres of the University? College Composition and Communication 60.4 (2009): 765-89. Print.

---. Understanding ‘Transfer’ from FYC: Preliminary Results from a Longitudinal Study. Writing Program Administration 31.1/2 (2007): 65-85. Print.

Mapping the Questions from Composition Forum 26 (Fall 2012)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/26/map-questions-transfer-research.php

© Copyright 2012 Jessie Moore.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 26 table of contents.