Composition Forum 27, Spring 2013

http://compositionforum.com/issue/27/

Material Affordances: The Potential of Scrapbooks in the Composition Classroom

Abstract: A multiliteracies pedagogy has renewed our interest in materiality, or how the physical text interacts with the author’s choices and the context to contribute to the message, yet little attention has been paid to materiality in analog texts, such as the scrapbook, even though this medium contains affordances (capabilities and limitations) that encourage active engagement with the materiality of composition. This essay demonstrates the pedagogical value of the scrapbook for how it encourages student composers to select, appropriate, and redesign external cover materials to communicate the message inside the book and how it emphasizes the haptic sense (touch). In short, the scrapbook assignment is pedagogically important because it teaches students the concept of affordances and demonstrates to them how materiality impacts design, composition, and rhetorical choices; it also provides a low-tech, low-stakes entry into multimodal composing and reflexivity on the rhetorical decision-making process.

During my first semester as an assistant professor, I integrated a multimodal assignment into my first-year writing classrooms. I explained to students that a multimodal composition was one that incorporated multiple semiotic modes, such as audio, video, alphabetic text, or still images, to convey meaning. I had assigned multimodal projects as a graduate teaching assistant and had been pleased with how students negotiated the writing according to their audience, purpose, and rhetorical strategies. I had also recently created multimodal audio and video essays myself as part of a graduate course and was familiar with the process and some issues that may arise when integrating multimodal assignments (regarding access, time, revision, assessment). I was teaching in a traditional classroom at the time (it did not even have a projector), and I knew it would be a challenge to require students to create digital projects where some of these issues existed. I thus decided to allow students to create their multimodal essay in whatever medium they wanted (video essay, collage, comic strip, etc.) and to use whatever modes they chose (alphabetic text, still or moving images, sound, etc.). The main requirement was that students combined at least two modes (audio and video, text and image, etc.) into their composition. In this particular assignment, students were asked to interview and observe a person, place, activity, or future career and then compose a multimodal profile essay on this subject.

Students created both digital and non-digital, or analog, essays. Digital projects ranged from video documentaries to audio essays, while analog essays included collages, scrapbooks, comic strips, and typed essays with images. As I assisted students throughout the creation and production of their multimodal compositions, one medium used by several students caught my attention: the scrapbook. The scrapbook is a somewhat common assignment in composition classrooms (e.g., Goodburn and Camp; Shipka, Sound) and composition textbooks (Faigley, George, Palchik, and Selfe). The scrapbook assignment is perceived as less intimidating than large-scale audio and video projects, which makes it attractive to composition instructors interested in introducing multimodal composition into the classroom but who may not have the technical expertise, technological resources, or time to assign digital compositions. Scrapbooks also fit into the multi-genre/media/disciplinary/cultural research project that Robert Davis and Mark Shadle advocate as an alternative to the traditional “modernist” research paper (418), thus extending their appeal.

Although familiar with the scrapbook genre, I had never assigned one in the classroom. However, when working with students throughout the composing process and assessing their final products, I made several observations that emphasized the pedagogical value of the scrapbook. First, these scrapbooks moved beyond the traditional genre and extended the definition of a scrapbook. As an avid scrapbooker myself, I knew what scrapbooks were supposed to look like. I even appreciated the extra embellishments you can buy to adorn your scrapbook (stickers, die cuts, stencils, corner punchers, journal pens, etc.). Yet, these students did not go to the craft store and buy a pre-made album like I always had done; instead, they constructed their own. They remixed, reshaped, and reformed materials into their own version of a scrapbook, thus expanding the meaning of what counted as a scrapbook and using the medium innovatively. Second, students seemed to understand their choices in relation to the materiality of the text by utilizing the external cover to convey the message inside the book. Students fashioned and constructed the album cover to assist the inside pages of the book in representing meaning, thus underscoring the message and highlighting the materiality of the piece to readers. Finally, these students added materials that called attention to the haptic, or tactile, mode. The texture, surface, and feel of the material functioned as a rhetorical device to connect to readers and reinforce the message they wanted to send. In short, scrapbooks contain unique affordances{1} (capabilities and limitations) that allow students with or without technical skills to actively engage the materiality of the composition. Unlike the view of some who hold that scrapbooks are not rigorous enough and “may be remote from any improvement of writing” (Gorrell 266), I argue that scrapbooks highlight materiality and can benefit students in their rhetorical awareness, critical thinking, literacy skills, and transfer of writing concepts from one domain to another. As such, the scrapbook is a pedagogically and rhetorically appropriate assignment for the composition classroom.

In this essay, I use three illustrative examples to demonstrate how both teachers and students can benefit from the inclusion of a scrapbook assignment in writing classes. I argue that scrapbooks lead student composers to consider how materiality works with message and audience. By emphasizing the material dimensions of composing, the scrapbook emerges as a medium that can actually convey its message through its materiality, which makes it an extremely valuable medium for teaching about materiality and affordances. Furthermore, the scrapbook draws attention to the often-overlooked haptic mode: not only do students have another modal composing choice, but they can also utilize the haptic mode to represent and communicate meaning. Finally, the scrapbook assignment is pedagogically appropriate because it emphasizes non-digital multimodal composing, which Shipka argues is lacking in our discussions on multimodality (Toward),{2} and it provides students and instructors with a low-tech, low-stakes entry into multimodal composing. Ultimately, this essay establishes the pedagogical significance of scrapbooks by underscoring how scrapbooks serve as a lens to teach materiality, affordances, the haptic mode, and rhetorical choices.

Materiality in Theory

Multimodal composition provides unique opportunities for writers to consider how semiotic modes (such as visual, verbal, aural, tactile) and media (or the technology on which information is delivered or stored) work together to convey meaning (see Cope and Kalantzis; Jewitt; New London Group; Selfe). What makes multimodal composition especially distinctive from traditional alphabetic print writing is its emphasis on the “material dimensions of literacy” (Shipka, Toward 5). Materiality refers to (a) the diverse contexts surrounding writing—such as the “social, cultural, political, educational, religious, economic, familial, ecological, political, artistic, affective, and technological webs (Wysocki, Opening 2)—and (b) how these contexts contribute to the message (Kress, Design; Kress and van Leeuwen; Manovich).{3} Materiality is thus an “emergent property” that appears when the physical text interacts with the author’s choices and contributes to the message (Hayles 33). Materiality “occurs in all texts we consume, whether print or digital, research essay or technical instruction set. . . . [It also] occurs when we produce any text as well” (Wysocki, Opening 7). This attention to materiality has encouraged scholars to examine it in relation to a variety of areas, including writing centers (Sheridan), copyright law (Burk), distance education (DePew, Fishman, Romberger, and Ruetenik), infrastructure (DeVoss, Cushman, and Grabill), billboards (Sheridan-Rabideau), students’ new media projects (Sorapure), and the print medium (Bernhardt; Bolter; Trimbur).

The results of examining writing in terms of its materiality are numerous, especially for student composers. First, materiality affords students a wide range of possibilities for conveying and representing their meaning (Haas; Kress, Gains). As Debray reminds us, “[A]spects of layout and design are constitutive of the message itself” (75). Instructors now better understand and attend to “the layers and patterns behind the products of new-media composing” (DeVoss, Cushman, and Grabill 37), which makes materiality an essential concept to include in our curriculum. Second, materiality merges form and content so that student writers understand how the material form of the composition impacts the message. Through materiality, they come to recognize that even the choice of page alignment, layout, spacing, and typeface contribute to the meaning of a composition and learn how to make deliberate choices about materials, content, modes, and media so they will convey the message they intend. Another result of emphasizing materiality is that student composers come to understand the media and modes in which they are learning, writing, and communicating (DePew et al. 63) and thus become more ethical and thoughtful about the ways these choices impact their message and audience (Wysocki, Opening 7, 13). A fourth effect of materiality is that students realize the “dynamic interactivity” between themselves, their work, and their readers (Hayles 130). One final result is that materiality brings attention to often-overlooked semiotic modes, such as the haptic. Lawrence Frank points out how tactile communication often gets displaced by other, more visible, modes of communication, even though it is a primary communication form (38-39). Pedagogies that emphasize materiality, however, foreground these semiotic modes and make them more noticeable, thus providing students with even more modal choices when composing.

In short, materiality leads students to consider how form and content work together to convey and represent meaning. When students consider materiality, they create artistic, provocative texts that meet their own rhetorical purposes and extend the medium of the scrapbook. Such awareness supplies student composers with the potential to create additional meanings in their compositions and to better understand the choices they make in both traditional and non-traditional writing assignments. Materiality is thus an extremely valuable addition to the composition classroom.

Materiality and the Scrapbook

In order to better understand the ways students use the medium of the scrapbook in the classroom, it is important to first situate the scrapbook as a cultural, historical, and embodied artifact so that readers will better understand the ways students draw from and extend scrapbooks to meet their own rhetorical ends, particularly in terms of materiality. Scrapbooks, like other genres, draw on “available designs” (New London Group) that link them to the design and production of similar texts that have been created, changed, restructured, and passed down from generations of scrapbook makers.{4} In their earliest embodiment, in the late seventeenth century, scrapbooks were much like commonplace books (Ott, Tucker, and Buckler), mostly used by educated men to record and list quotations, proverbs, and achievements (Moss 1). Throughout the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, as cheap printing, chromolithography, and advertising emerged, scrapbooks began to emphasize personal expression more so than recording or listing. During this time, scrapbooks were “a material manifestation of memory—the memory of the compiler and the memory of the cultural moment in which they were made” (Ott, Tucker, and Buckler 3), and they symbolized the authors’ personal and cultural identity (Bronner 130). Scrapbookers selected and arranged trade cards, newspaper clippings, personal art and mementoes, and actual “scraps” mass-produced by publishers explicitly for the purpose of collecting (Buckler and Leeper; Ott, Tucker, and Buckler; Tucker). Scrapbooks even contained elaborately designed covers, engraved clasps, brass locks, and exquisite paper (Allen and Hoverstadt 16; Robinson xxxi).

As scrapbooks were more closely linked to individual expression, they also became more associated with women, a trend that continues today. Viewed as an “acceptable” female activity (Gear; Tucker 3, 10), they were especially appealing to adolescent girls and upper- and middle-class women (Buckler and Leeper 1). The idea of “womanhood” often dominated these scrapbooks, particularly in the artwork that depicted domesticity, family, and the female form (Buckler and Leeper 6). The female scrapbooker “pursued feminine identity through feminine means, making individualized use of the material commonly manipulated by women of her background and upbringing” (Buckler and Leeper 6). Unlike men, whose scrapbooks mostly included public documents, such as newspaper clippings, published poems, and letters to the editor (see Marsh), women focused on self-representation and feminine identity. In sum, scrapbook composers historically used the medium to define and understand one’s self, express emotion, be creative, and offer social, historical, and personal commentary on life and culture in a given place and time (Buckler and Leeper 1-2; Bunkers 8).

Scrapbooks today still construct identities through their scrapbooks and are mostly used as a personal or family artifact that involves arranging photos, clippings, and other memorabilia into an album. Scrapbooking continues to thrive as a commercial business. Craft stores sell supplies including albums, decorative paper, stamps, scissors, and cut-outs; they even encourage scrapbookers to construct their albums together in their stores. Most scrapbookers, like me, use “readymade” albums where we buy the scrapbook at the store and merely fill up the inside pages. However, scrapbooks do afford an additional level of physicality to them when scrapbookers construct or redesign scrapbooks in ways that emphasize materiality and help convey the meaning inside the book. Much like medieval and early modern books in which authors, editors, and publishers took great pains to ensure that the text’s materiality was showcased (see Olsen; Petrucci), scrapbooks, as a material object, have the potential “to mirro[r] and reinforce[e] the message of the text” (Richardson 88, 89). Primarily because of the extra choice of cover design and binding material, scrapbooks afford an additional level of physicality to convey the message, thus offering a way to represent the message through the physical medium. These distinctive affordances merge form and content and make the scrapbook a unique medium for emphasizing materiality.

This overview of materiality and its application to the scrapbook medium underscores the scrapbook’s potential in emphasizing materiality and the unique affordances offered through this medium, including conveying the message through the medium itself and emphasizing the haptic mode. In the next section, I explain the methods of my rhetorical analysis of student scrapbooks and then use three case studies to highlight what students learned from the scrapbook assignment. I ultimately argue that scrapbooks encourage students to consider how materiality impacts the design of the composition, the message, and the reader. I end this essay by giving specific recommendations on how instructors can enhance the learning experience when using scrapbooks or other multimodal assignments in the classroom.

Methodological Approach

To examine what students learned about materiality and affordances in multimodal composing, I examined scrapbooks and reflective letters composed by eighteen first-year composition students who came from three different institutions. Thirteen of the participants self-identified as white, two as African-American, two as Hispanic, and one as Asian-American. All scrapbooks were composed by females, and the three examples shown here were my own students. The same written assignment prompt was used in all courses. This assignment asked students to profile a person, place, activity, or future career and compose a multimodal essay combining at least two modes (audio and video, visual and print, etc.) (See the Appendix for a copy of the assignment.) Students conducted primary research of interviews and observation on their subject. Students also determined their audience, modes, and media (students were not asked or required to compose scrapbooks).{5} When they submitted their final drafts, they also submitted a reflective letter analyzing the rhetorical objectives and decisions they made concerning message, medium, modes, audience, purpose, context, and design. All instructors introduced several concepts to students during the invention and composing process, including the following: rhetorical principles; the genre of profiling; principles of visual design; and concepts regarding multimodality, including mode, medium, materiality, available designs, and affordances. Students understood that they were being asked to compose a multimodal project as a way to apply those ideas. All policies regarding human subjects at each university were followed.{6}

Scrapbooks were analyzed by a rhetorical analysis approach, which provided a lens through which I could better understand what was happening in these scrapbooks and determine some properties that made them unique. Specifically, I examined rhetorical elements of the compositions, including material, textual, multimodal, and audience decisions. Reflective letters were analyzed through discourse analysis methods. The three examples I include were chosen as case studies because they are representative of the ways students confront materiality when deciding upon medium and message in scrapbooks and because they were my own students.{7} They also demonstrate the creative and rhetorical flexibility students establish throughout the creation process, as well as the important connections they make about the relationship between their work and their readers, specifically in terms of materiality, affordances, and the haptic mode. Though scrapbooks are a limiting medium, I include snapshots of these scrapbooks and describe them so that the material and tactile nature the authors sought to embody and communicate may be visualized and experienced by the reader.

The Scrapbook Compositions: Material Design, Message, and Readers

These scrapbooks emphasize the ways students use the material form in rhetorically effective ways, thus bringing value to the scrapbook assignment in composition classrooms. Specifically, in their scrapbook compositions, students consider material, modal, and rhetorical choices that highlight how materiality, medium, and message interact to make meaning, thereby heightening the possibilities for readers to recognize the material and sensory aspects of the scrapbook compositions as well.

Evelyn’s Flipbook

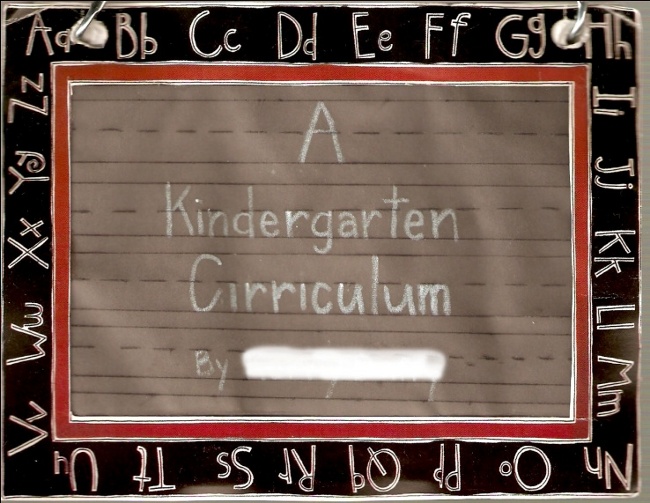

For her scrapbook, Evelyn, an aspiring kindergarten teacher, profiled a kindergarten classroom. Her scrapbook contains a cover, binding, and multiple pages, but what makes it unique is how she constructed it. Evelyn bought index cards with pre-punched holes at the top and two silver rings, and then affixed them together to make her own scrapbook (Figure 1). She fashioned her scrapbook in the form of a flipbook, an item commonly used by teachers in elementary schools to teach, reinforce lessons, and read stories. In fact, from the external cover to the inside pages, Evelyn’s entire scrapbook is crafted to reflect kindergarten. She even uses simple concepts and basic facts typical of what kindergarteners learn to convey her message. Her design choices on the cover and the interior pages give readers the sense that teaching is fun, creative, and dynamic and that children of this age are original, imaginative, and artistic. She conveys these ideas through color, font style, and art. Even the misspelled word in her title, albeit an error, allows readers to engage with the scrapbook and wonder if this, too, is a strategic choice made by the author to take us back to those days of spelling tests. Her flipbook becomes a visual representation of elementary school, and each aspect ties into the school theme. Evelyn’s decision to craft her scrapbook in the form of a flipbook indicates how she is thinking critically about materiality and the affordances of a scrapbook.

Figure 1. The cover to Evelyn's flip chart.

Evelyn’s flipbook cover also exemplifies the rhetorical and design choices she makes, choices that align with her purposes to profile a kindergarten classroom. She foreshadows her topic by framing the cover with the lower- and upper-case letters of the English alphabet, which illustrates the way we write when we learn to recite and trace letters as children. She also fastens grey paper resembling a chalkboard to the back of the page, uses chalk to compose her title, and writes her name in print (rather than cursive), correctly, between the lines, choices that not only communicate the theme of her scrapbook but that also show thoughtful planning and reflection on her subject: kindergarten. In short, Evelyn uses the physical and material features of the scrapbook medium, including the title, illustrations, pasted materials, binding orientation, and the flipbook as a representative object, to communicate the content of her text in an unusual and creative way.

In addition to designing her material cover in rhetorically sophisticated ways, she also learns to compose a creative and aesthetic cover that appeals to readers, drawing them in and making them excited to read this book. The cover of her flipbook functions almost like an introduction in a print essay: it provides a hook for readers and incites our curiosity. However, it does more than a print introduction: the visual and material features actually encourage readers to make meaning before ever opening the book, to ponder and wonder what we might find when we open the book. Not only does the cover provide a hook, but it also reflects her subject matter. Her cover is fashioned in the same way good teachers should make instructional lessons stimulating for students. Evelyn writes, “One of a teacher’s responsibilities is to make things engaging, and even though a flipbook is a really simple form of engagement, it is reflective of the notion that teachers should inspire and motivate students and encourage them to be creative.” In reflecting on why she constructed the cover in this way, she wrote that she viewed “[o]riginality and imagination [as] characteristics valued and encouraged in elementary school” and wanted her cover to convey the same. Evelyn’s choices indicate that she considers how her material medium interacts with the message to communicate.

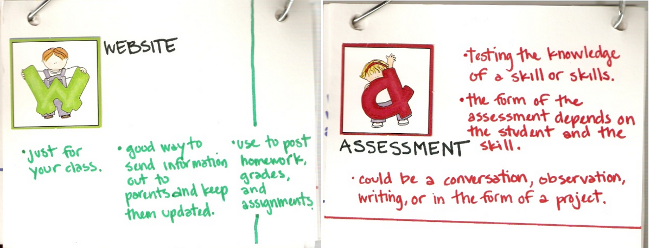

Evelyn’s flipbook cover is not the only part of the book that emphasizes materiality—the inside does as well. The interior pages are designed to be reminiscent of another learning tool commonly used in schools—flashcards. These pages utilize a question-answer format and are arranged in alphabetical order, with one letter designated to each page from A-Z. Each page then corresponds to the first letter of the word-theme for that page, as in Figure 2 where “A” represents “Assessment” and “W” represents “Website.” The bulleted points further elaborate on that specific word-theme. In my conversations with her in class, Evelyn explained that she chose these material representations for her external cover and interior pages because she wanted to connect readers to materials and objects that were most likely part of their own educational histories. In short, Evelyn’s compositional and rhetorical choices indicate that she is consciously and actively trying to construct meaning that is significant and profound.

Figure 2. Sample pages inside Evelyn's scrapbook.

In addition to emphasizing materiality, Evelyn’s scrapbook indicates that she learned to invite readers to make meaning through a variety of modes. While most of the genres and mediums we teach and assign in our classrooms emphasize the verbal and, more recently, the visual, the scrapbook has the potential to highlight oral and haptic modes as well. The flash cards in Evelyn’s scrapbook, for instance, point to the oral mode through their evocation of recitation and memorization. As readers notice the alphabetic letters located throughout the project, the alphabet song may come to mind, which also evokes an oral component. Readers are also invited to construct meaning tactilely. The cover, for example, invites us to explore the various textures and materials with our fingers and to make meaning through memory and touch. Perhaps we smudge the chalk-based title or touch the brad binding and recall the times we used these objects in school. Through the senses of touch and hearing (and sight), we return to our own memories and compare them to what we are reading/experiencing. We become personally invested in the project because of our own fond memories of elementary school. What makes Evelyn’s scrapbook especially valuable is how readers are invited—encouraged even—to draw on multiple senses to interpret the scrapbook. Using all of our senses to read a text brings an added level of investment and attachment to the composition. Scrapbooks as a medium tend to encourage this level of reader participation.

All in all, Evelyn’s creation of this flipbook indicates she is aware of materiality’s role in composing a scrapbook. As her comments, external cover, and interior pages suggest, Evelyn’s stylistic and material choices are no accident; they are rhetorically and visually placed to give readers a sense of the message of her flipbook. She materially, multimodally, and rhetorically fashions the outside of her scrapbook to convey her subject matter and carry some of the meaning contained within it. She also encourages readers to make meaning by drawing on experiences many of us have had. In fact, her material choices indicate that she realizes how valuable this aspect is to composing a rhetorically successful scrapbook. In addition, Evelyn’s composing decisions that utilize multiple senses to make meaning add another level to what it means to consider readers in the invention stage of composing. As I will elaborate later, such awareness of materiality and readers enriches the pedagogical experience by showing students and instructors the many different ways that scrapbooks can be envisioned and designed, thus demonstrating the endless possibilities and affordances available when composing scrapbooks.

Katy’s Wooden Book

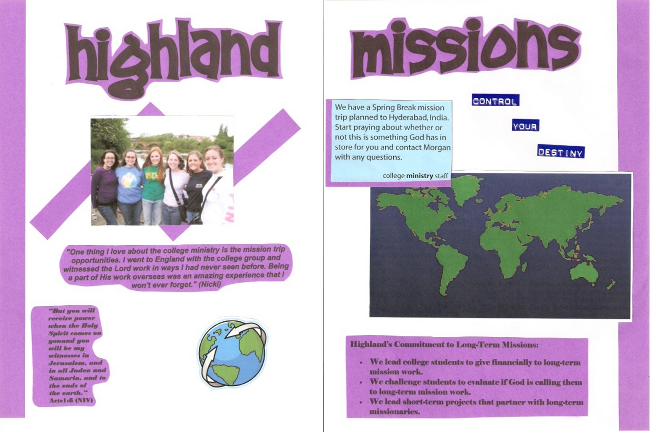

Like Evelyn, Katy also considers how materiality interacts with modes, message, and media in her scrapbook composition. As a new college student, Katy used the assignment as an avenue to learn more about the college ministry at her church. Katy’s goal is twofold: to inform readers—her college peers at a private religious school looking for church homes —about the college ministry and persuade them to visit. Through a combination of words and images, she claims that the church provides a wonderful place to praise and worship God, make wonderful friends, and engage in service activities that help others. One section, for instance, informs readers of the college ministry’s involvement with foreign missions and then invites them to consider participating (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Katy’s description of the mission work at her church.

By utilizing various available designs of scrapbooking, including, but not limited to, a range of colors, interesting fonts, unique cut-outs, aesthetic images, and creative textual descriptions, Katy informs readers about the church and urges them to visit. She ends her scrapbook with an original poem in which she makes one final attempt to persuade readers to visit the church (Figure 4). This conclusion leaves the decision to visit up to the reader, but Katy has worked diligently to influence it.

Figure 4. Katy's closing poem.

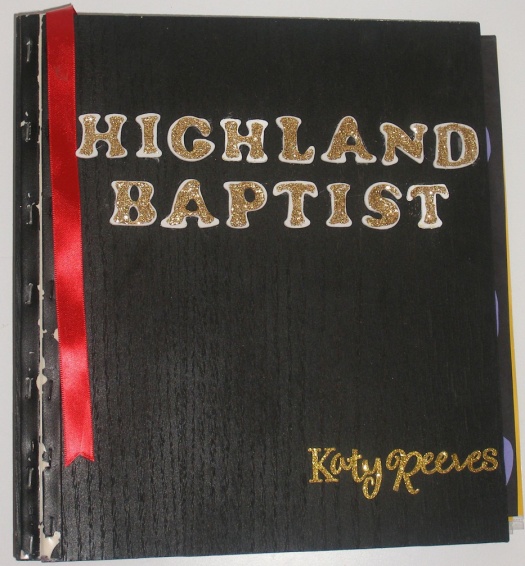

The scrapbook itself is more traditional than Evelyn’s: it is a conventional book held together in a three-ring binder. What makes Katy’s scrapbook compelling, however, is how she builds a scrapbook to reflect her subject matter in a stimulating way. Rather than buying a pre-made scrapbook at a craft store, she constructed her own. She worked with her dad to cut, nail, and staple wooden material together to form a book. She painted the book black, inscribed her name—italicized and in gold—on the bottom right cover (which coincides with the personalized engraving practice on Bibles), and used embossed gold and white stickers to arrange the title Highland Baptist (representing Holy Bible). She even attached a red satin ribbon to the binding (Figure 5), thus creating a “wooden Bible,” as she liked to call it. Katy’s intended audience will immediately make associations between Katy’s scrapbook cover and traditional Protestant Bibles. In my conversations with her during the design process, Katy expressed how she wanted readers to get a sense of the subject matter before they opened the book, so she planned out how she would craft a wooden Bible scrapbook to convey this meaning. Her ongoing reflections during the design process and her consideration of various rhetorical elements demonstrate how Katy uses the material medium of the scrapbook to further her purposes and her message; the outside cover actually assists in conveying the message.

Figure 5. Katy's “wooden Bible” scrapbook.

Katy’s choice to use wood for the cover material was an important rhetorical and artistic choice as well. By encasing her essay in wood, Katy connects two major aspects of the Christian life: stability and the cross. First, according to Katy, the wooden material represents a “solid foundation,” sturdy and strong enough to endure “bad weather” and hardships: “Since God is the solid foundation of a Christian life, I wanted a solid, durable foundation used on my medium to represent this permanent aspect as well.” Secondly, Katy views the physical cross on which Jesus died to be “a huge part of Christianity” and wants the reader to be able to touch this same type of material while reading and holding her book, perhaps allowing them to contemplate the cross on which Jesus was crucified and make meaning materially. Because her readers (peers at a religious institution) would most likely know the story of Jesus on the cross, this association of wood to Christianity would hopefully occur when these readers engaged with the material scrapbook.

Katy’s decision to construct a wooden scrapbook indicates a sophisticated awareness of her subject matter and her audience. In fact, these physical materials invite the reader to interact with the scrapbook composition in ways not necessarily accomplished with printed books or digital texts, even the digitized scrapbook. As readers, we are impelled to linger over the cover, running our hands along the different surfaces, textures, and materials, pausing before opening it to contemplate its meaning. We are also encouraged to make connections to our previous knowledge about Bibles, church, and wood before considering how Katy’s own design choices align with and extend these meanings. In addition, because some readers recognize the values embedded in the object, its materiality, specifically through touch, works to persuade. Now that we are feeling this wooden Bible, we, too, are part of this church in a small way. We are holding this Bible in much the same way that churchgoers carry their Bibles to church, which connects us to others who take their Bibles to church or who read their Bibles at home. Katy implies that one only need open this wooden Bible to learn more about this place, not forgetting to use the red bookmark as we do so. Katy’s rhetorical decisions indicate how much she is learning about rhetorical principles, materiality, and affordances of the scrapbook medium. Her numerous strategic decisions during and throughout the composing process point to the potential pedagogical significance an assignment like the scrapbook has for the composition classroom in teaching students these important concepts.

In sum, Katy’s selection of a wooden Bible signifies a representative medium most apt for her purposes, a visual and aesthetic reflection of her profile of the college ministry at her church. In this instance, the physical materiality of the scrapbook works together with our own understandings of what a Bible looks like to convey meaning: The inscription of Highland Baptist in the same gold font typical of some Bibles, the red ribbon, the black color, the wooden texture, and the embossed name provide evidence of how Katy conveys her message by using physical materials. The project’s material form appears to reflect its author’s understanding of what a Bible looks like and brings another layer to the message Katy conveys in the inner pages of her scrapbook. Scrapbooks such as Katy’s highlight how the material medium of the scrapbook can assist in conveying meaning and how materiality becomes one of the many rhetorical decisions students can make when composing. They also show how students are not limited by conventional scrapbook forms but instead envision and create scrapbooks that align with their rhetorical goals and purposes.

Sana’s Patient Chart

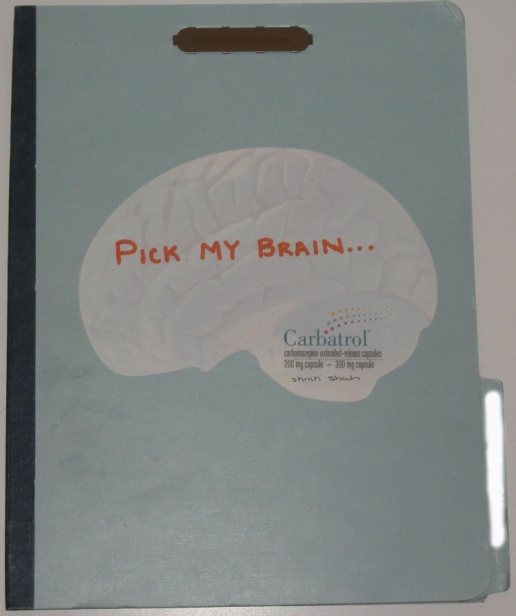

Like Evelyn and Katy, Sana also recognizes how the material medium interacts with the message, modes, and reader in her scrapbook composition. Sana profiled a psychiatrist for her multimodal essay and chose to use an actual patient chart as the physical form for her scrapbook essay (Figure 6). Standard in doctors’ offices, patient charts allow medical professionals to keep track of symptoms, diagnoses, and medications. Sana’s selection of a patient chart as her representational scrapbook form shows how she extended the medium by choosing an object that best reinforced and represented her subject matter.

Figure 6. Sana’s patient chart profiling a psychiatrist’s job.

In addition to the material form itself, the external cover to Sana’s scrapbook functions rhetorically as well. She designs her scrapbook cover to “captivate the reader’s attention” and give readers a hint as to the topic of the essay. She writes in her reflective letter that she chose the title, Pick My Brain, because of the nature of psychiatric appointments, stating, “Since doctors ask endless questions, especially in the first few sessions, many people feel as though their brains have been picked by the end. I thought ‘Pick My Brain’ would be a rhetorically appropriate title.” Sana also writes her name on the folder’s tab, which serves the dual function of showing authorship and indicating to readers that the name might represent a patient’s name listed on a real patient chart. Overall, the material cover is constructed and bound together in rhetorical ways, communicating a message through its physical medium, one that adds to and extends the one she promotes within the book. Her design choices in the external cover supplement the patient chart scrapbook and allow readers to understand what this essay is about well before they open the book. Her rhetorical awareness of materiality and its impact on the ways readers interact with the text is evident in the material design choices of her scrapbook.

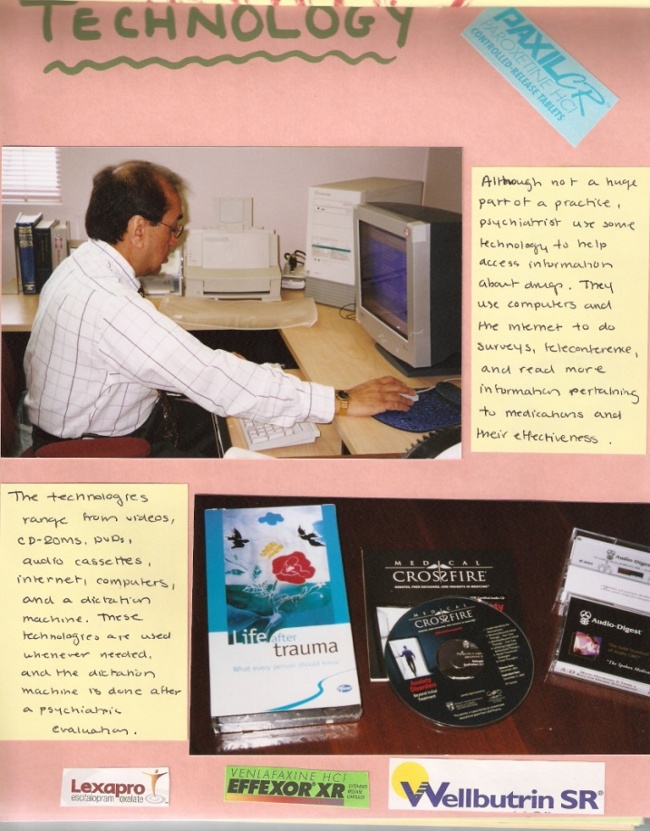

Sana also understands that her material choices encourage readers to use multiple senses to interpret the scrapbook. As we read the patient chart, we participate in the same act professionals in this field do every day. We open and close the chart and interpret what is written there. We notice the blue color and feel the firmness of the binding material. We manipulate the interior pages by opening the brad and inserting and extracting pages as we see fit (see Figure 7 for an example of the inside of the book). In addition, we may even recall the smell of a doctor’s office or the feel of the couch we sat on during a consultation. Furthermore, because of the way Sana invites readers to use and experience the patient chart both materially and physically, we can even pretend we are the doctor reading an actual patient’s chart and making sense of what is contained within the pages. At the same time, however, we also put ourselves in the position of the patient, as if this was our own patient chart and we get to read what is written about us. In sum, the materials and medium Sana selects for her project indicate that she is actively considering how materiality works in conjunction with medium, audience, and modes, including the haptic, to communicate a message. Her rhetorical awareness of materiality and its impact on the ways readers interact with the text is evident in the material design choices of her scrapbook.

Figure 7. Sample page in Sana’s patient chart describing technologies used by psychiatrists.

Materiality, Message, and Audience: A Discussion of the Scrapbook

The three projects highlighted here indicate the myriad ways student scrapbook composers combine physical materials with the scrapbook medium to reflect the message. Even in their choice to use the scrapbook as their composing medium, they draw on available designs yet extend the possibilities as well. Additionally, these projects emphasize how the rhetorical choices scrapbook composers make regarding materiality, modes, and media situate readers in specific ways by encouraging them to engage with the material medium in multiple ways. In this section, I flesh out these results and point toward why the scrapbook assignment is valuable in the composition classroom. I end by giving specific pedagogical recommendations for how instructors can use the scrapbook assignment to teach materiality and affordances and thus enhance the learning experience for students.

Rhetorical Decisions of Materiality and Message

As these projects emphasize, student scrapbook composers design their compositions so that the material medium and everything it entails helps convey the message. Through an emphasis on materiality, these projects make explicit the New London Group’s metaphor of Design by highlighting the multiple semiotic resources afforded by scrapbooks. These semiotic resources show us how physical and material features of mediums—even the illustrations, title, images, book format, and binding orientation (left-side like a traditional book or top-side like Evelyn’s and Sana’s)—represent the message. Student authors consciously decide how to physically design their scrapbooks so that the text’s materiality communicates additional meanings to the argument already occurring within the composition itself. They consider how material choice and binding decisions work so that the material medium assists in reflecting the message, which is a unique affordance of scrapbooks. These projects bring together material design (or form) with message (or content) so that “form does not override content” but “is, in fact, understood as itself part of content” (Wysocki, Sticky 149). In short, through the process of constructing a scrapbook, students engage in complex rhetorical decision-making about how the medium and the material form function rhetorically and then use the available semiotic resources to envision, design, and create that composition in rhetorically effective ways. These modal affordances make the scrapbook a particularly beneficial assignment for composition classes.

The examples presented here also demonstrate that the scrapbook medium distinguishes itself from digital and other analog texts such as books and readymade scrapbooks in that it encourages composers to consider materiality and message in a tangible way: by highlighting notable affordances such as using the material cover to reflect the message and attending to the haptic sense. Certainly, the scrapbook medium is not the only medium that emphasizes materiality, but it does so in an extremely obvious way. Particularly through the extra design choices of the cover and the binding material of the book itself, scrapbooks afford an additional level of physicality to convey the message, thus offering a way to represent the message through the physical medium. Print and digital texts no doubt attend to issues of materiality and message. In fact, desktop publishing and printing capabilities provide writers with the materials and software to design every aspect of their compositions to fit their message and to do so at a high level of quality. These compositions also invite user participation and manipulation of the mediums’ affordances. Just consider how mobile phones, touchscreens, tablets, websites, and digital books do so. What is different, however, is that the composer of these texts is still somewhat limited by the constraints of the medium. Think about, for instance, a print research paper, an audio public service announcement, or a video essay. These mediums are more physically and materially “fixed” in that the message conveyed in these mediums is constrained within the medium itself. While scrapbooks face similar constraints, they do offer the potential for writers to manipulate the medium for their own purposes and consider rhetorical choices of material design. Scrapbooks allow authors to choose how to physically portray their message by both using and extending the available designs as they create such scrapbooks as a flipbook, wooden Bible, or patient chart. They highlight “the complex and highly distributed processes associated with the production of texts” (Shipka, Toward 13). When writers can decide which physical medium best represents their message, they respond in rhetorically, visually, and linguistically sophisticated ways and are truly able to choose the best available means of persuasion.

This study also reveals how students make use of the available designs of scrapbooks by ascribing new meaning to the scrapbook genre. Students here were not limited to traditional definitions of scrapbooks. To them, a scrapbook did not just signify a readymade album with empty pages; it did not even entail being sold in stores. Rather, scrapbooks—at least as envisioned in the writing classroom—included homemade books and remixed items fashioned out of materials relevant to the purpose of their essay, thus broadening the definition of what counts as a scrapbook. They might also be comprised of binding material not typically associated with scrapbooks but nonetheless purposeful and rhetorical, such as Evelyn’s flipbook or Sana’s patient chart. Students, moreover, even extended the function of the artifact so that meaning is not only conveyed within the interior pages but also through the external features of the medium chosen, as in Katy’s wooden Bible. In sum, these students appropriated a wide and consciously chosen array of established objects—flipbook, Bible, patient file—and redesigned them to fit their own goals, purposes, and contexts. These decisions thus extended what was possible for the medium and showed us the endless material choices for scrapbook composers.

Finally, students also reshaped their identities by seeing themselves as meaning-makers, as active contributors of knowledge. Students were not merely passive but rather took control of the composing process, going beyond the assignment to become active producers of creative, innovative texts that extend and expand the medium’s conventions and possibilities. They were able to see “how agency and materiality are entwined as they compose” (Wysocki, Opening 6). Consequently, the scrapbook assignment provides unique opportunities for authors to consider how design, message, and materiality contribute to identity construction. It also encourages development of specific rhetorical and multimodal skills that will be useful as students participate in a wide range of literate activities in both their professional and personal lives.

Authors and Audience

The specific attention to the material design of scrapbooks also suggests that students can become rhetorically aware of the impact their compositions can make on readers. Scrapbook compositions, in fact, invite students to think about the relationship between authorship and audience in meaningful ways. As a medium that engages materiality and form, readers are encouraged to engage fully in the semiotic modes utilized. We are reminded through these projects that we become “active designers of meaning” (Cope and Kalantzis 7). Since every authorial decision contributes to the way readers perceive meaning, students must consider the various semiotic modes at work as they design their texts. These decisions about the crafting of a text help determine readers’ interpretations concerning the text’s meaning, the author, and themselves. A scrapbook utilizing, for instance, the haptic mode, might be more persuasive for an audience who considers church more than just an intellectual argument or for people who respond physically to a church service. Scrapbooks can thus encourage readers to synthesize and interpret the content and the form; readers can be engaged not only in the physical nature of holding the text but also in deciphering the meaning. Scrapbook authors are thus “depicting” the world rather than “telling” the world, leaving room for multiple and varied interpretations (Kress, Gains 16). Because of their emphasis on materiality, scrapbooks call attention to the ways that rhetorical decisions position readers and encourage them to engage with the composition, thus illuminating the importance of analyzing an audience.

One particular mode highlighted through the scrapbook is the haptic. Students implicitly understand that touch impacts how readers make meaning, and, consequently, they use this knowledge to add additional textures and fabrics to their scrapbooks. They use the haptic mode “consciously and deliberately for purposes of representation and communication” (Kress, Multimodality 185). Scrapbook compositions thus answer Ron Fortune’s call “to help [students] learn to become comfortable with a range of semiotic modes and to match effectively verbal and visual [and also haptic] resources with rhetorical circumstance” (52). The addition of tactile interpretation to the range of senses used to make meaning through these compositions engages readers in tangible ways. Since tactile modes are viewed as an intimate mode of communication (see Frank)—consider how society views touch in a private and personal manner— in ways that other modes are not, when readers make sense of the text in tactile ways, they connect with the text and the message in a physical and personal manner. These various material surfaces thus contribute to the meaning-making already occurring. Designing the cover, then, became a rhetorical act for these authors: their choices determine how the reader engages with the text. This physical closeness between reader, text, and author provides unique communicative possibilities for scrapbooks as well as distinctive pedagogical value in the classroom. Instructors can use the scrapbook as an avenue to teach students to better understand the haptic mode, including a discussion of ways this mode might be incorporated into other mediums. Further research might investigate the ways readers engage this haptic sense as they process the meanings of scrapbooks and other mediums and what additional communicative possibilities exist.

Pedagogical Recommendations

Scrapbooks offer unique potentials to the composition classroom by highlighting materiality and giving students new opportunities to represent their purposes, message, and audience. I end this essay with pedagogical recommendations for using the scrapbook as an avenue into better understanding the concepts of materiality, affordances, and modes.

- Emphasize the scrapbook’s potential for the medium to convey the message. While the scrapbook may not be the first genre one might consider when looking for alternative modes to teach or use in the classroom, it does separate itself from print, digital, and other analog assignments, particularly in what it can teach students about merging material design and message, form and content. Oftentimes, our instruction focuses on content without paying as much attention to matters of form. These scrapbooks, however, seamlessly integrated the two so that the material form actually participated in meaning conveyance. This affordance of the scrapbook medium to reflect its content is unique and profound. Virtually no other medium can do this in the same way that scrapbooks can. Highlighting the scrapbook’s potential for the medium to convey the message in both class instruction and throughout the composing process can provide students even more opportunity to develop new and creative approaches to this assignment.

- Use the scrapbook to teach the concept of affordances. The notion that modes and mediums have affordances—or capabilities and constraints that make possible or limit certain options—is one that cannot be overlooked when discussing multimodality. This study examined some affordances of the scrapbook, including material opportunities of the external cover, meaning conveyance through both form and content, remixing and refashioning the notion of what counts as a scrapbook, and attending to the haptic mode. Some of these capabilities are even unique to the scrapbook. The scrapbook medium also has some constraints as well. For one, a scrapbook is not as easy to revise as other mediums. The physical material is more fixed and permanent (for instance, you cannot un-paste a picture you have glued to a page without damaging the page). This limitation makes peer review more difficult and somewhat hinders global revision advocated through process writing. Yet, the assignment also offers students the potential to critically consider their rhetorical choices in advance. Knowing that revising for organization or remaking an entire book might be more difficult, students must plan ahead more during the invention stage. Such an understanding brings value to the assignment no matter the level (first-year to graduate) in which it is assigned. In short, the possibilities and constraints emphasized through scrapbooks provide instructors with a great example of teaching affordances in writing.

- Use the scrapbook as an entry into multimodality. The scrapbook can be assigned at the beginning of the semester as a way of introducing rhetorical and multimodal concepts like materiality, affordances, audience, and design. Students are probably already somewhat familiar with scrapbooks, which might make it less intimidating. Also, it can be considered a “low-tech” assignment, which reduces the number of issues that arise when incorporating digital assignments into the classroom. Perhaps the scrapbook assignment would also allow instructors who may not have much access to technology to try their hand at multimodal composition, or it might help students who are resistant to or less technologically literate in digital technologies to succeed. For these and other reasons, the scrapbook is a useful and valuable assignment for the composition course.

-

Incorporate formal and informal reflections throughout the composing process so students can further consider their rhetorical composing choices. Students became more aware of what was going on in their projects when they engaged in reflection with their instructors and peers during the composing process as well as when they wrote a reflective letter at the end. As students composed their scrapbooks, they made rhetorical decisions and engaged in reflective dialogue with their instructors and their peers over these decisions. They made decisions, reflected on these decisions, solicited feedback from peers and instructors, and revised their essays accordingly. These ongoing reflections throughout the process highlighted to students the multiple and complex decisions they must make as they planned and composed and led to greater rhetorical awareness during the composing process.

Asking students to write a reflective letter over their objectives and choices after the fact also offered them a chance to analyze the intentional and unintentional decisions they made and retroactively justify them. Through this type of reflection, students came to understand what they were doing and how their choices impacted their meaning. By “describing, evaluating, and sharing the purposes and potentials of their work” (Shipka, Toward 16), students realized that their words even became part of their assessment. Though students might not have been metacognitively aware of each and every decision throughout the composing stage, reflection enables them to see additional ways their compositions communicate meaning, a practice that brings in an artistic element of the meaning-making. Students even emphasized in their reflective letters a heightened level of awareness for their audience as they designed their books, which is an important skill we want students from all disciplines to develop. This practice of reflection is common in composition, but these projects remind us how important it is to encourage students to understand, explain, and justify their decisions so that they can better understand how decisions they make as they compose impact the message and the audience.

- Encourage students to pay attention to physical features of texts. This study highlights the important role material design plays in meaning and interpretation. When we solely focus on content, argument, organization—or, to extend the metaphor, the “inside” of the book—then we lose out on the role material features play in constructing and conveying meaning. As we as instructors tighten our own grasps on materiality, we should encourage students to pay attention to these physical features of texts so that they can extend the scrapbook medium even further. We should also continue to examine materiality’s role in other analog compositions.

- Use the scrapbook to teach students about the haptic mode. Although our writing classrooms emphasize verbal and visual modes, they do not typically pay as much attention to the haptic mode. As demonstrated here, the haptic mode’s importance in representing and communicating meaning in scrapbooks is evident. Today’s widespread use of touchscreen and mobile technologies has made such awareness another important component of communication. Although not a digital composition, the scrapbook could “disturb the marriage between comfortable writing pedagogies that form our disciplinary core and the entire range of new media for writing” (Faigley and Romano 49). The scrapbook’s illumination of the role of touch in making meaning highlights the importance a multimodal pedagogy has in our classrooms.

- Before assigning a multimodal project, be clear on the outcomes and how the assignment will be assessed. Assessing multimodal compositions can be more difficult because we are not as familiar with assigning or evaluating these projects. Likewise, students are less familiar composing multimodal projects, especially in an academic setting, and they worry about how they will be graded and assessed. We must, therefore, always keep our goals for the assignment in mind. It is easy to be so awed by what students can do with multimodal projects that we lose sight of the outcomes we established at the beginning. Therefore, I suggest writing out the outcomes on the assignment sheet and creating an evaluation rubric that clearly states how students will be assessed. Then, call students back to these criteria again and again throughout the composing process. Laying bare your assessment criteria will allow students to be more confident completing such projects.

- Include multimodal assignments that allow students to choose the modes and mediums that best fit their rhetorical purposes. For the most part, our assignments ask students to compose the same essay in the same mode using the same medium. For example, we ask students to write a literacy narrative, an audio public service announcement, a written proposal, or a research paper. Our textbooks are even divided into these genre types. However, if we are truly to embrace a multiliteracies classroom where “all available means of persuasion” are at the students’ disposal, then we might also try creating assignments where students choose the modes and mediums that will best meet their rhetorical purposes and audiences. As this study shows, when students are able to choose these aspects of composing, they respond in provocative ways.

In conclusion, this study presents an invitation for teachers to consider the numerous rhetorical possibilities of scrapbooks as a multimodal assignment in the composition classroom. Attending to materiality, affordances, and other aspects of multimodality as we teach can amplify and extend the rhetorical choices students have as they compose. As instructors assist students in becoming more rhetorically aware of the composing situations they confront, we can encourage them to think critically about the relationships between medium and message, form and content, and writer and reader, all in hopes of expanding compositional possibilities. If students embrace the notion that the medium can carry the message, they will come to understand the importance of and possibilities for all design choices, no matter how insignificant these choices might seem. By reflecting on the material aspects of the texts, such as binding material and orientation, cover material, color, images, and scripts/fonts, students might see the abundant representational and multimodal possibilities for many different multimodal compositions.

Appendix: Multimodal Profile Essay Assignment

Goals

- Analyze rhetorical elements (audience, purpose, genre, context, mode, medium, message, etc.) and integrate them successfully into your project.

- Employ the affordances (capabilities and limitations) of the medium in effective rhetorical ways.

- Apply the characteristics of description, narration, argument, and field research (interview and observation) into a multimodal composition.

Assignment Overview

For this assignment, you will compose a multimodal essay profiling a person, place, activity, or future career. Your multimodal profile essay will include primary research in which you observe and interview your subject, much like a reporter on an assignment. You will then compile this information into a multimodal composition that both informs and engages readers. A multimodal essay is one that combines two or more modes into a single composition (video, collage, scrapbook, audio public service announcement, comic strip, brochure, or hypertext website). An example of a multimodal essay might be a video that integrates still images, moving images, printed words, and sound, such as music and voice-overs.

A Few Cautions

- Choose a subject for your profile in which you are genuinely interested and about which you will enjoy learning more.

- Observations, visits, and interviews all require planning and note-taking. Don’t wait until the last minute. Have good, open-ended questions written out before your interview. Plan ahead! Be prepared to conduct follow-up interviews so your focus won’t have gaps in it.

Evaluation

I will evaluate your project based on the following criteria:

- Considers rhetorical elements that will impact the outcome of your project

- Employs the affordances of the medium in effective rhetorical ways

- Characterized by careful design that helps to convey meaning

- Has a specific focus or theme (creates a dominant impression of the subject)

- Effectively synthesizes information rather than presents a straight reporting of facts

- Reveals the writer’s attitude toward the subject and offers an interpretation of it

- Effectively incorporates the field research

- Has evidence of careful planning

- Considers how the modes you choose work together to convey meaning

- Effectively analyzes the audience

- Maintains a reflective focus

- Is creative and insightful

- Fulfills all criteria for the assignment

Notes

I am grateful to the students who participated in this study and helped me see the scrapbook differently. This study was supported in part by funds from the University Research Committee and the Vice Provost for Research at Baylor University.

- Affordances are the representational qualities of a semiotic mode that make it distinctive. They both enable and constrain and offer potentials and limitations, which make possible or exclude certain meaning-making possibilities (see Cope and Kalantzis; Kress and van Leeuwen). (Return to text.)

- As an analog composition, scrapbooks question our tendency “to equate terms like multimodal, intertextual, multi-media, or still more broadly speaking, composition with the production and consumption of computer-based, digitized, screen-mediated texts (Shipka, Toward 7-8). (Return to text.)

- In this essay, I borrow my conception of materiality from Anne Frances Wysocki (Opening) who bases her understanding on Bruce Horner’s explanation in Terms of Work for Composition: A Materialist Critique. Horner explains that the materiality of writing for writing teachers and in writing classrooms includes the following: writing technologies; socioeconomic conditions contributing to writing production; networks that distribute writing; publishing controls; global power relations; particular subjectivities; social relations; physical classroom conditions, faculty resources; working conditions; the teachers’ “lived experience;” and institutional relationships—both local and global (xviii-xix). (Return to text.)

- Available Designs suggests that composing is not completed in a vacuum but rather is “continuous with and a continuation of particular histories” (New London Group 75). It involves “the constant reshaping, the Redesign of the materials, which reflect the prior designs of others” (Kress, “Design” 158). (Return to text.)

- I did not require students to compose in a single medium or specific modes because I wanted to follow Shipka’s multimodal task-based composing framework (see “Multimodal”) and due to constraints of access and time. (Return to text.)

- This study was approved by the Institutional Review Board of each university, and formal written permission was obtained from each participant. All names used here are pseudonyms, except for Katy’s, who granted me permission to use her real name because deleting it would have altered the project’s meaning. All quotes, unless noted, come from the reflective letters students submitted with their projects. (Return to text.)

- Other students used such materials as artists’ sketch pads, poster board, and canvas to bind their scrapbooks and invite readers to interact with their compositions in specific ways. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Allen, Alistair, and Joan Hoverstadt. The History of Printed Scraps. London: New Cavendish Books, 1983. Print.

Bernhardt, Stephen A. Seeing the Text. College Composition and Communication 37.1 (1986): 66-78. Web. JSTOR. 7 Aug. 2007.

Bolter, Jay David. Writing Space: The Computer, Hypertext, and the History of Writing. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1991. Print.

Bronner, Simon. Visible Proofs: Material Culture Study in American Folkloristics. Material Culture: A Research Guide. Ed. Thomas Schlereth. Lawrence: U of Kansas P, 1985. 127-53. Print.

Buckler, Patricia P., and Kay C. Leeper. An Antebellum Woman’s Scrapbook: An Autobiographical Composition. Journal of American Culture 14 (1991): 1-8. Print.

Bunkers, Suzanne L. ‘Faithful Friend’: Nineteenth-Century Midwestern American Women’s Unpublished Diaries. Women’s Studies International Forum 10.1 (1987): 7-17. Print.

Burk, Dan L. Materiality and Textuality in Digital Rights Management. Computers and Composition 27 (2010): 225-34. Web. ScienceDirect. 16 March 2011.

Cope, Bill, and Mary Kalantzis, eds. Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. London: Routledge, 2000. Print.

Davis, Robert, and Mark Shadle. ‘Building a Mystery’: Alternative Research Writing and the Academic Act of Seeking. College Composition and Communication 51.3 (2000): 417-46. Print.

Debray, Régis. Media Manifestos. Trans. Eric Rauth. 1994. London: Verso. 1996. Print.

DePew, Kevin Eric, T. A. Fishman, Julia E. Romberger, and Bridget Fahey Ruetenik. Designing Efficiencies: The Parallel Narratives of Distance Education and Composition Studies. Computers and Composition 23 (2006): 49-67. Print.

DeVoss, Danielle, Ellen Cushman, and Jeffrey T. Grabill. Infrastructure and Composing: The When of New-Media Writing. College Composition and Communication 57.1 (2005): 14-44. Print.

Faigley, Lester, and Susan Romano. Going Electronic: Creating Multiple Sites for Innovation in a Writing Program. Resituating Writing: Constructing and Administering Writing Programs. Ed. Joseph Janangelo and Kristine Hansen. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1995. 46-58. Print.

Faigley, Lester, Diana George, Anna Palchik, and Cynthia L. Selfe. Picturing Texts: Composition in a Visual Age. New York, NY: Norton, 2003. Print.

Fortune, Ron. ‘You’re Not in Kansas Anymore’: Interactions Among Semiotic Modes in Multimodal Texts. Computers and Composition 22 (2005): 49-54. Web. ScienceDirect. 11 December 2009.

Frank, Lawrence K. Tactile Communication. The Rhetoric of Nonverbal Communication: Readings. Ed. Haig A. Bosmajian and Douglas Ehninger. Glenview, IL: Scott Foresman, 1971. 34-56. Print.

Gear, Josephine. The Baby’s Picture: Woman as Image Makers in Small-town America. Feminist Studies 13.2 (1987): 419-43. Web. JSTOR. 21 January 2011.

Goodburn, Amy, and Heather Camp. English 354: Advanced Composition: Writing Ourselves/Communities into Public Conversations. Composition Studies 32.1 (2004): 89-108. Web. Academic Research Complete. 15 Sept 2011.

Gorrell, Robert. The Traditional Course: When Old Hat Is New. College Composition and Communication 23.3 (1972): 264-70. Web. JSTOR. 3 May 2012.

Haas, Christina. Writing Technology: Studies on the Materiality of Literacy. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum, 1996. Print.

Hayles, N. Katherine. Writing Machines. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology P, 2002. Print.

Jewitt, Carey. Multimodality and New Communication Technologies. Discourse and Technology: Multimodal Discourse Analysis. Ed. Philip Levine and Ronald Scollon. Washington DC: Georgetown UP, 2004. 184-95. Print.

Kress, Gunther. Design and Transformation: New Theories of Meaning. Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. Ed. Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. London: Routledge, 2000. 153-61. Print.

---. Gains and Losses: New Forms of Texts, Knowledge, and Learning. Computers and Composition 22.1 (2005): 5-22. Web. ScienceDirect. 11 March 2010.

---. Multimodality. Multiliteracies: Literacy Learning and the Design of Social Futures. Ed. Bill Cope and Mary Kalantzis. London: Routledge, 2000. 182-202. Print.

Kress, Gunther, and Theo van Leeuwen. Multimodal Discourse: The Modes and Media of Contemporary Communication. London: Arnold, 2001. Print.

Manovich, Lev. The Language of New Media. Cambridge: Massachusetts Institute of Technology P, 2001. Print.

Marsh, Alec. Thaddeus Coleman Pound’s ‘Newspaper Scrapbook’ as a Source for The Cantos. Paideuma 24.2/3 (Fall/Winter 1995): 163-93. Print.

Moss, Ann. Commonplace-Books and the Structuring of Renaissance Thought. Oxford: Clarendon P, 1996. Print.

New London Group. A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures. Harvard Educational Review 66 (1996): 60-92. Print.

Olsen, Gary R. Eideteker: The Professional Communicator in the New Visual Culture. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication 34.1 (1991): 13-19. Print.

Ott, Katherine, Susan Tucker, and Patricia Buckler. An Introduction to the History of Scrapbooks. The Scrapbook in American Life. Ed. Susan Tucker, Katherine Ott, and Patricia Buckler. Philadelphia: Temple UP, 2006. 1-25. Print.

Petrucci, Armando. Writers and Readers in Medieval Italy: Studies in the History of Written Culture. Ed. and Trans. Charles M. Radding. New Haven: Yale UP, 1995. Print.

Richardson, Brian. Inscribed Meanings: Authorial Self-Fashioning and Readers’ Annotations in Sixteenth-Century Italian Printed Books. Reading and Literacy in the Middle Ages and Renaissance. Ed. Ian Frederick Moulton. Turnhout, Belgium: Brepols, 2004. 85-104. Print.

Robinson, William W. ‘This Passion for Prints’: Collecting and Connoisseurship in Northern Europe during the Seventh Century. Foreword. Printmaking in the Age of Rembrandt. By Clifford Ackley. Boston: Museum of Fine Arts and New York Graphic Society, 1981. xxvii-xlviii. Print.

Selfe, Cynthia L., ed. Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton P, 2007. Print.

Sheridan, David M. All Things to All People: Multiliteracy Consulting and the Materiality of Rhetoric. Multiliteracy Centers: Writing Center Work, New Media, and Multimodal Rhetoric. Ed. David M. Sheridan and James A. Inman. Cresskill, NJ: Hampton P, 2010. 75-107. Print.

Sheridan-Rabideau, Mary P. Kairos and Community Building: Implications for Literacy Researchers. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy. 11.3 (2007). Web. 4 October 2011.

Shipka, Jody. A Multimodal Task-Based Framework for Composing. College Composition and Communication 57.2 (2005): 277-306. Print.

---. Sound Engineering: Toward a Theory of Multimodal Soundness. Computers and Composition 23.3 (2006): 355-73. Print.

---. Toward a Composition Made Whole. Pittsburgh: U of Pittsburgh P, 2011. Print.

Sorapure, Madeleine. Five Principles of New Media: Or, Playing Lev Manovich. Kairos: A Journal of Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy. 8.2 (2003). Web. 18 Nov 2011.

Trimbur, John. Composition and the Circulation of Writing. College Composition and Communication 52.2 (2000): 188-219. Print.

Tucker, Susan. Reading and Re-reading: The Scrapbooks of Girls Growing into Women, 1900-1930. Defining Print Culture for Youth: The Cultural Work of Children’s Literature. Ed. Anne Lundin and Wayne Wiegand. Westport, CT: Greenwood P, 2003. 1-25. Print.

Wysocki, Anne Frances. Opening New Media to Writing: Openings and Justifications. Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for Expanding the Teaching of Composition. Ed. Anne Frances Wysocki, Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia L. Selfe, and Geoffrey Sirc. Logan: Utah State UP, 2004. 1-41. Print.

---. The Sticky Embrace of Beauty: On Some Formal Relations in Teaching about the Visual Aspects of Texts. Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for Expanding the Teaching of Composition. Ed. Anne Frances Wysocki, Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia L. Selfe, and Geoffrey Sirc. Logan: Utah State UP, 2004. 147-97. Print.

Material Affordances from Composition Forum 27 (Spring 2013)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/27/material-affordances.php

© Copyright 2013 Kara Poe Alexander.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 27 table of contents.