Composition Forum 35, Spring 2017

http://compositionforum.com/issue/35/

Welcoming Linguistic Diversity and Saying Adios to Remediation: Stretch and Studio Composition at a Hispanic-Serving Institution

Abstract: In this program profile, we describe the stretch/studio program recently implemented at the University of New Mexico. This program responds both to an institutional move away from remediation and to the large number of linguistically and racially diverse students at our institution. In this profile, we describe the new program’s curriculum, which focuses on and values the linguistic and cultural diversity of our students. We also share the initial results of our assessment of the program and our plans for the future. We offer this profile as a successful model for adaptation by other writing programs that are also implementing stretch/studio courses and/or that have a growing number of linguistically and culturally diverse students on their campus.

I am so glad…we were able to show that our potential is greater than the result of a standardized test.

– Student in Studio Composition Course

In the fall of 2012, we, Drs. Davila and Elder, were newly hired assistant professors in the Rhetoric and Writing Program at the University of New Mexico (UNM) who were appointed as assistant directors to the Core Writing Program, a series of 100- and 200-level composition courses that fulfill core curriculum requirements. Outside of our purview was the Introductory Studies (IS) “remedial” writing course offered to students with low ACT/SAT English placement scores (below 19/450) and taught by faculty from the local community college on UNM’s campus. Up until fall 2014, about 35% (and up to 45%) of incoming first-year UNM students placed into one or more of UNM’s IS remedial courses. Although the IS students were enrolled in a UNM course and paid UNM tuition, they were held at arm’s length from the university as they received neither graduation credit nor a curriculum that aligned with UNM’s core writing program. In short, UNM administrators sent a message that these developing writers were not theirs to “deal with.” Like many other scholar-educators committed to student success and developing writers, we were troubled with the message being sent to students as well as the unethical situation of accepting students into the university and charging them for tuition when they would not receive college credit for their efforts.

In response to the previous remediation approach at UNM, we turned to best practices in teaching developing writers: stretch and studio courses. Both course models offer additional support to students as they complete their required, credit-bearing, first-year composition courses and allow students to earn college credit in the process. Knowing that stretch and studio programs had been successful at other institutions (Adams, et al., Glau, Grego and Thompson, Soliday and Gleason), we prioritized the development and implementation of these courses at UNM. As of fall 2014, we have replaced 100% of the IS writing courses with two curricular options for students: ENGL 111/112: Composition I/II (stretch) and ENGL 113: Enhanced (studio) Composition.

We modeled our two-semester stretch course after that of Arizona State University (Glau) and stretched our traditional English 110 (Accelerated Composition) course across two semesters. Students can begin the stretch sequence in summer or fall. Our studio program, like many others, is a one-semester course that requires an additional class session per week with smaller student groups ranging from seven to twelve students (depending on the length of the class period). Both our stretch and studio courses address the same student learning outcomes of the traditional Accelerated Composition model and contribute to student success by a) reducing the negative effects of using an inherited placement model (ACT scores) and providing credit for these college-level writing classes, b) helping our diverse student body develop the writing skills they will need to succeed in future writing classes at UNM and improve their chances for academic success more broadly, and c) changing the campus culture with regard to supporting developing writers.

While stretch/studio courses aren’t new, elements of our program are unique. Specifically, we have created a first-year writing curriculum to support our student population—a student population that reflects the nationally growing multilingual student body that, if not already a major student demographic at most institutions in the country, soon will be. As is often said on UNM’s campus, we serve the emerging U.S. student demographic of tomorrow, today. This curriculum is used in both the stretch and studio models allowing us to offer both delivery methods while streamlining instructor training and program administration. Finally, we have used our experiences and successes in the stretch/studio program to influence the core writing program more broadly, including the curriculum content for the “traditional,” face-to-face accelerated first year composition course, which now aligns with that of the stretch/studio models. In the pages that follow, we describe our stretch/studio curriculum, and we argue that our program is both successful and a possible model for other institutions.

Stretch and Studio Composition at UNM: Valuing Students’ Linguistic Diversity and Expertise

In contrast to the previous IS “remedial” writing course, which followed a current-traditional approach—emphasizing developing a main idea, organizing ideas into and within paragraphs, and expressing oneself in “standard written English”—our stretch/studio curriculum works toward the same student learning outcomes as the rest of the core writing curriculum. As such, it uses a rhetorical genre approach to help students develop habits and approaches to writing. However, the stretch and studio courses also provide additional support (in different ways) to students throughout the writing process and recognize that stretch/studio students might be more likely to need help adjusting to academic writing and academic culture more broadly. Specifically, students whose home discourse communities overlap the least with academic discourse communities need help identifying and analyzing discourse community conventions in order to be able to succeed within them (Bartholomae; Bizzell; Gee). Additionally, the curriculum puts language and discourse at the forefront, positioning students as linguistic experts and inviting diversity into the classroom.

The University of New Mexico is a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) with large numbers of first-generation students (almost half of all undergraduates) and significant economic diversity among its students. According to UNM’s fall 2015 enrollment report, the three races/ethnicities that represent the majority of UNM’s undergraduate student population are Hispanic (46.5%), White (35%), and Native American (5.7%). The beginning first-year students comprise slightly higher percentages of Hispanic students (52%), and lower percentages of white students (32%) and Native American students (3%). While our institution does not (unfortunately) collect data about students’ linguistic diversity nor their self-identified status as native or non-native speakers of English, we know from census data that approximately 36% of New Mexicans speak a language other than English at home: 80% report that Spanish is used in their home and 10% report that Navajo is spoken (Ryan). Additionally, New Mexico recognizes both English and Spanish as official languages, publishing government documents in both languages. Given the fact that the majority of our undergraduate student population (84%) is comprised of in-state students, we feel confident in our assumption that our students are regularly exposed to linguistic diversity in their homes and communities regardless of whether they would characterize themselves as bilingual or non-native English speakers. Like Matsuda, we reject the notion that “the college composition classroom can be a monolingual space” and assert that “the presence of language differences is the default” (649).

In a 2006 article in WPA: Writing Program Administration, Ann Preto-Bay and Kristine Hansen argue that the percentage of linguistically diverse students in higher education institutions is rapidly increasing (38) and, in response to this changing student population, they call for a redesign of composition programs (43). Furthermore, they suggest that this redesign will require an “increased attention to language and cultural issues” (51) as “many or most [students of the near future]…will need further support in academic English and in their transition and adaptation to postsecondary academic culture” (49). Although Preto-Bay and Hansen are largely interested in the growing international student population, we argue that the projected growth of Hispanic students in higher education suggests that other kinds of multilingualism are likely to increase as well. Indeed, we argue that the racial and ethnic diversity as well as the multilingualism that we already see at UNM are likely to become more common at all US higher education institutions.

Like Matsuda and Preto-Bay and Hansen, many other scholars aim to improve writing instruction for multilingual students. As one recent example, scholars call for a translingual approach (Horner, et al.) that sees language difference as the norm and positions competence in multiple languages or language varieties as more advantageous than mastery in one, narrowly defined dialect. Other scholars (Young; Canagarajah) argue for the blurring of boundaries between languages and language varieties, noting that the more instructors and students see code-meshing—the use of multiple languages/language varieties in one utterance or occasion—as always already occurring, the more composition instructors can allow, acknowledge, and value linguistic diversity.

Our stretch/studio curriculum responds to these scholars’ call for translingualism, code-meshing, and/or curricula that acknowledges and values linguistic diversity. A central curricular component of our stretch/studio program is acknowledging and making space for the linguistic and cultural diversity of our students at UNM. As many of our students come from linguistically diverse, “non-traditional” backgrounds and are often the first in their families to enroll in college, we begin stretch and studio courses with a required unit on discourse communities. This unit encourages students to view the diversity they bring with them to campus as an advantage rather than a disadvantage. The major writing assignment for unit one asks students to create a website that profiles one of their discourse communities. Students analyze the reciprocal relationship between their identities, languages, and discourse communities from a position of “expert” when profiling a single discourse community and its unique language usage. (See Appendix 1 for a sample assignment prompt.) The assignment begins the semester by not only valuing students’ knowledge and introducing them to the affordances of multimodal composition but also by creating a welcoming space for students to bring their linguistic diversity into the classroom (though, they do not always choose to do so). Students’ understanding of discourse communities is carried forward into the curricular units that follow.

The second required unit (taught either as the first unit in the second semester of stretch or the second unit in studio) provides students the opportunity to explore the languages, cultures, and literacies of where they are now—at UNM—by writing about a campus resource. (See Appendix 2 for a sample assignment prompt.) The other units of the course vary across sections; however, assignments continue to help students explore the topic of discourse communities. For example, in some sections, students focus on where they are headed and perform a preliminary investigation of an academic major in preparation for the more in-depth examination of disciplinary genres they will perform in their next required composition course. Throughout these units, students are encouraged to view these new discourse communities or their new knowledge about literacy as adding to (rather than replacing or subtracting from) the literacies they bring with them to campus.

Using The “Extra” Time: The Pacing of Our Stretch/Studio Courses

Traditionally, our composition courses require three writing sequences per semester, and each sequence includes two low-stakes writing assignments that help students to practice and build to the major writing assignment. At the end of the semester, students produce a portfolio of their work, including two revisions of major writing assignments and a reflection on their learning across the semester. The stretch curriculum differs most notably from our traditional composition courses in the first semester when students complete two sequences (as opposed to three), allowing more time for drafting, workshopping and support throughout the writing process. (The third stretch sequence begins the second semester of the stretch course.) In addition, the end-of-the-first-semester portfolio hinges on a learner’s plan, which still reflects on students’ growth over the semester but also includes a plan for the next semester. In the learner’s plan, students set goals for themselves as writers, identify strategies to help them achieve those goals, and note how they will self-assess their progress toward those goals. The second semester of stretch follows the traditional pacing of composition classes at UNM with three sequences.

The use of the studio time varies by instructor. Some instructors prefer to use the studio time as student working time. In this case, students sign a contract about how they will use the time, and the instructor checks in with students individually and provides support depending on each student’s needs. Other instructors use the time to support students in the writing process through guided activities. For example, if students have just received a new assignment, the studio time might be spent annotating the assignment prompt and decoding the expectations as well as brainstorming topics. Most instructors use a mix of these two approaches over the course of a semester.

Like the Accelerated Learning Program (ALP model) implemented by Peter Adams and others at Baltimore Community College (Adams, Gearhart, Miller, and Roberts), our studio sessions meet directly after the main class session. However, our studio classes do not mix studio students with non-studio students. Although we acknowledge the benefits of the diverse classroom model in ALP (such as reducing stigma and the possibility of non-studio students serving as role models [Adams, et al. 62]), we worried that our studio students might feel embarrassed or “othered” within a heterogenous class because of the required 1-credit hour lab. Conversely, we were troubled that the non-studio students would miss out on important instruction and learning by not being able to attend the additional weekly class session offered to their studio counterparts.

All sections of stretch and studio composition are held in computer labs so students can work on assignments/course projects and receive feedback from instructors and peers throughout the writing process.

Removing Stigma

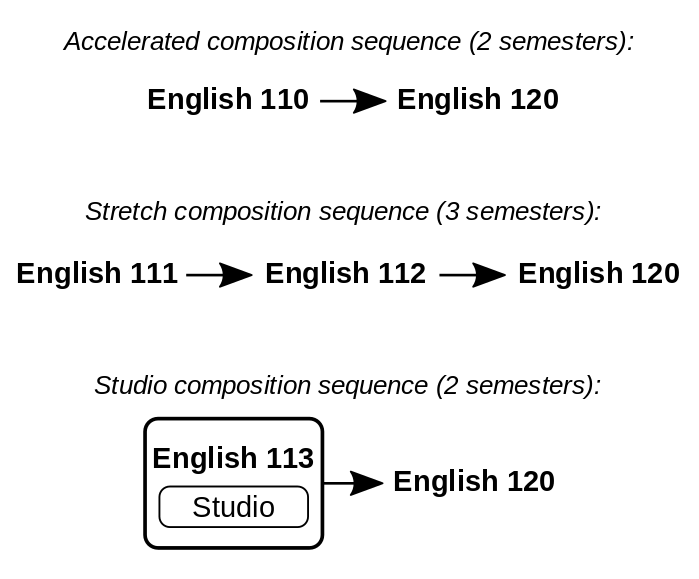

When we added stretch and studio composition to our first-year writing program, we carefully renamed and renumbered all of the composition courses in an effort to reduce the possible stigmatizing effect of being placed into stretch or studio. Our traditional composition course, in which students with the highest ACT/SAT scores (19-25/450-600) enroll, has been given the lowest course number (ENGL 110) and renamed Accelerated Composition. The two-semester stretch course (ENGL 111/112), for students with ACT/SAT placement scores below 15/380, has been given a higher course number and given the unmarked name Composition I and II. The studio course, for students with ACT/SAT placement scores between 15-18/380-440, has been numbered ENGL 113 and named Enhanced Composition. All students who take stretch, studio, or Accelerated Composition must also take Composition III (English 120) to complete their first-year writing requirement. See Figure 1 for a visual representation of the three different paths through first-year composition at UNM.

Figure 1. Three Pathways for First-Year Composition at UNM

Assessing the Curriculum

In order to assess the effectiveness of the stretch/studio program, in addition to pass rates, we collected, with IRB approval, the following student data: 1) student pre- and post-surveys measuring students’ attitudes about and confidence in writing, 2) end-of-semester, in-class, student focus groups, and 3) students’ final course grades. The success of the stretch/studio program at UNM thus far is clearly reflected in the stretch/studio students’ pass rates, which match or exceed those of students enrolled in UNM’s traditional composition course (English 110). Our combined stretch and studio pass rates are approximately 90%; the traditional composition course pass rate is 87%. Additionally, students who begin the composition sequence in stretch or studio pass the next required composition course (ENGL 120: Composition III) at about 93%, which is close to the 95% pass rate for students who first take ENGL 110.

Students’ responses to the survey following their completion of studio or the first and/or second semester of the two-course stretch curriculum clearly illustrate their overwhelmingly positive attitude about the course. All stretch and studio students reported feeling “confident” to “extremely confident” on 16 survey items related to their levels of confidence as writers, including the ability to organize and defend their ideas in writing, revise their papers, and use grammar and punctuation to clearly express their ideas. When asked how confident students were that the course had prepared them for the writing they will do in the next semester of the course, for the writing they will do in other university courses, and the writing they will need to do outside of school, stretch students’ responses averaged “very confident” and studio students’ responses ranged from “confident” to “extremely confident.” Students’ satisfaction with the stretch and studio courses in terms of content, the assignments, and the instructor ranged between “satisfied” to “extremely satisfied.”

Stretch and studio students’ open-ended responses offer representative, anecdotal evidence that supports the quantitative survey data shared above, while giving students a voice in the assessment of the program. As one student wrote,

I had a great experience with this course. I wasn't exactly confident in how well it was going to go. However I love my instructor and how she teaches. She provides examples for every assignment and doesn't continue teaching until everyone in the class understands. She gives great direction which makes it easier to do the assignments. Overall I would recommend this class/program to anyone. Stretch is definitely one of, if not my favorite class.

This sentiment was shared by a majority of respondents, including this student: “I really enjoyed [the course] and feel lucky to have been given the opportunity to take it. The instructor was always very helpful and the class discussions were always fun to have. I learned a lot and I'm looking forward to continuing the class next semester.” In addition, a number of students reported increased confidence in their skills as writers, as reflected in this student’s comment: “This program helped me a lot with my writing and understanding my skills as a writer. It was very helpful in the feedback that was given on each assignment and really helped to build my confidence.” Similarly, another student wrote, “I thought the program was really good for me. I feel more confident in my writing due to the program.” Finally, a number of students expressed their expectations that the writing skills they have developed in the stretch and studio program would transfer to their other courses: “This class helped me learn new and different strategies that I can now use throughout my college career.”; “This is a great course. It’s very helpful and it gets you prepared for your next courses.” Students completing the stretch program in fall 2014 and studio in spring 2015 showed increased satisfaction with the program on all accounts.

Ongoing Challenges, Moving Forward

We are pleased with our stretch/studio program and it’s recent success: as we mentioned, our pass rates are approximately 90%, meaning that, as of the end of spring 2015, more than 1,000 students have passed our stretch/studio course and earned credit that will count toward graduation. Just three years ago, those same students would have had to take a non-credit bearing “remedial” course first. Also, as our assessment has shown, students find stretch/studio to be rewarding and meaningful to their experiences at UNM.

However, we do face regular difficulties in maintaining this program. The first challenge is the high turnover in our instructor pool. Because we rely largely on graduate students to teach the first-year composition classes at UNM, we have many MA students who are only eligible to teach stretch/studio for one academic year after completing the stretch/studio practicum.{1} We are working to encourage more lecturers to take the practicum and teach for our program. However, even among the lecturer population there is high turnover as many lecturers do not have security of employment and choose to leave for other opportunities. Additionally, there are several other writing program initiatives (e.g., online writing classes, professional and technical communication, and linked courses) that graduate students and lecturers might choose to teach in, which means that even when we have trained teachers, they aren’t always available to continue to teach the stretch/studio courses as they seek out a variety of teaching opportunities.

In addition to the high turnover rate among our teachers, we also continue to struggle with our inherited placement system that relies solely on ACT scores. Although we know that placing students based on their ACT scores is ineffective, we have neither the human nor capital resources to explore other placement models at this time. Moving forward, an exploration of a directed self placement process will be a priority for the stretch and studio composition program coordinator.

Finally, our most frustrating challenge is that we have no recurring budget for the stretch/studio program (nor for the writing program more generally) despite repeated (and public) vocal support for the program from upper administration, including the dean, the provost, and the regents. While the teaching of the courses is covered by our department’s budget, there is no funding for the administration of the program and no guarantee that we will always be able to offer our stretch/studio practicum to train new instructors. This issue is compounded by the fact that we are assistant professors who need to amass publications to ensure tenure. While we both highly value the pedagogical and scholarly contributions of and the ethics addressed by the stretch/studio program, our department places the highest value on publications and counts program building as service work. As such, the development, assessment, revision, and coordination of this program does not count toward tenure and promotion and is currently uncompensated. To address this last issue—the budget—we are working with other administrators in the writing program to determine the feasibility of developing and publishing a required text designed to further support students in our first-year writing program. Though not perfect, this approach has been successful at other institutions and would allow us to move out of the Sisyphean cycle of devoting significant resources to pursuing a recurring budget year after year with no success.

Conclusion

In this profile, we argued that our stretch/studio program is a successful model of a writing program dedicated to valuing linguistic diversity and serving students who are often underrepresented in higher education. In addition to responding directly to the literature on linguistic diversity in our field, our stretch/studio program aligns with the national trend to reduce “remediation” in higher education. As other institutions follow this movement, we strongly encourage that they consider our model for making linguistic diversity the classroom norm. Beginning the undergraduate curriculum with a focus on the knowledge and expertise that students bring to the classroom works to position developing writers as students with unique strengths and resources who are fully capable of doing college-level work. As illustrated in our favorite student quote that begins this article (taken from an end-of-semester portfolio), students recognize this effort to position them as linguistically competent.

Certainly, there is room for improvement. We have found that our students regularly choose to create their discourse community profiles on high school social or athletic groups. As a result, their interrogation of the language of the community often doesn’t allow for a critique of the politics that lead to perceptions of monolingualism as both the norm and ideal. Nonetheless, we believe that the assignment—even when associated with a basketball team or TV fan group—helps students to grapple with the relationship between language and identity and begin to identify group values through an interrogation of language. This work creates a foundation on which the class can build when discussing politics and linguistic diversity at other points in the course.

Finally, we believe that a focus on students’ linguistic expertise will serve students and their instructors well across contexts and institutions. As such, we encourage other colleges and universities to turn to our program as a model that can be adapted to the student demographics, program outcomes, instructors’ training, and values of their institutions.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Sample Discourse Community Profile Prompt

Note: the full sequence includes a major writing assignment (MWA) and two small writing assignments (SWA) that lead up to and prepare students for the MWA. The prompt for the MWA, which references the two SWAs, is included here.

Major Writing Assignment (MWA): Discourse Community Profile

Instructor: (Adapted from) Soha Turfler

Our first Major Writing Assignment (MWA #1) is the Discourse Community Profile. For SWA (small writing assignment) 1, you created a guide to using the specialized language or genres of your discourse community. For SWA 2, you explored the social value of your discourse community and the role of the discourse community in shaping identity. For MWA #1, you will create a website profile of your discourse community. Your profile must include information about the role of language and/or genres within your discourse community.

Rhetorical Situation: This class is a discourse community, and we are all new to it. Every discourse community is influenced by its members and their experiences and expertise, and this class is no exception. This assignment gives you the opportunity to share some information about the expertise—especially language knowledge—that you bring with you as a result of your membership in other discourse communities. For this assignment, you are asked to create a website that will introduce the other members of the class to a discourse community of your choosing.

- Purpose: Your primary purpose is to inform your readers about your discourse community. However, you might also want to persuade your classmates to join the community. And you will likely strive to entertain them with humor, brief stories, rich descriptions and vivid details or images; all this makes reading the profile enjoyable and builds your ethos.

- Angle: Describe what’s interesting, important, or even essential about your discourse community, making sure to include information about this group’s unique use of language. For example, if you are profiling a discourse community of runners, you could describe the way that the language of the discourse community has shaped the way you see and interact with your surroundings or how it helps you to better interact with the main focus of the discourse community (running).

- Audience: Your classmates and I will be the primary audience for your website. We will use the sites to get to know each other’s interests and language expertise. The secondary audience might be future English students or other audiences interested in the UNM student body.

Description of the Genre: Profiles introduce and highlight the essential or noteworthy characteristics of an issue, person, community, product, service, or program. The essential purpose is to convey information and increase interest in the profiled topic. Profiles often incorporate anecdotes, quotes, and images to help illustrate the topic’s characteristics.

Writing Assignment Details: Using Weebly, create a website profiling a discourse community that you belong to outside of this class. In your website, you should include the following content: a creative title, an introduction to yourself and your discourse community, a description of your discourse community (including a focus on language and/or genres, a statement about the social value of your discourse community, and information about the social hierarchies in your discourse community), and links to other, relevant information.

Use of Modes: Keep in mind your audience’s expectations for websites. You are not only allowed but encouraged to use headings and subheadings in your website, to separate your content into more than one page within your website, and to incorporate images, videos, links, etc. when appropriate.

Reflection: In addition to your website, you must also submit a 1-2 page (single spaced) reflective commentary—in the form of a letter to me. The purpose of the reflective letter is to give you an opportunity to reflect on your writing, your writing process, and how you could improve your writing and/or process. In your reflective letter, you should address the following questions. Note that you do not need to address the questions in the order they are provided.

- What is the purpose of your website and how have you attempted to achieve this purpose?

- How did your intended audience influence your decisions as you composed your profile?

- What changes did you make in response to peer feedback? What peer feedback did you decide not to take into account during your revisions and why?

- What would you change about your website if you had more time, knowledge (about Weebly, for example) or resources?

- For each of the questions listed above, please give specific examples from your website.

- What Student Learning Outcome(s) do you understand better after having completed this assignment? What in the assignment helped you deepen your understanding?

- Choose two of the course Student Learning Outcomes and give specific examples of how this assignment helped you make progress toward those Student Learning Outcomes.

Your discourse community profile will be graded on the following: its attention to the genre of profile (30%), your response to the rhetorical situation described in this prompt (30%), the coherence of your website (25%), and the ethos you create within your profile (through tone, style, proofreading, citations, etc.) (15%).

Appendix 2: Sample UNM Resource Review Prompt

Note: the sequence includes a major writing assignment (MWA) and two small writing assignments (SWA) that lead up to and prepare students for the MWA. The prompt for the MWA, which references the two SWAs, is included here.

Major Writing Assignment (MWA): Review of a Campus Resource

Instructor: (Adapted from) Jeff Hunt

Points: 80 for the website, 20 for the reflection (100 total)

Purpose and Rhetorical Situation: This is the cumulative, MWA assignment in Sequence #2 and the assignment where you can show what you learned in your investigation of a UNM campus resource. For your SWA (small writing assignment) 1, you analyzed a document from your chosen resource in order to better understand that resource and to prepare questions before visiting the resource. For SWA 2, you completed an observation report in which you described your experience accessing or using the resource. In this assignment, you will demonstrate your understanding and developing mastery of the review genre by writing an informative and persuasive review of your chosen campus resource.

Your review should provide background information, though your primary aim should be to discuss what your experience has been like in using this resource. Think about common expectations and whether or not your resource meets, fails to meet, or exceeds those expectations. As with past assignments in this sequence, you are writing for your peers and instructors at UNM, though keep in mind a resource might also want to hear the feedback your review generates, or perhaps even administrators or organizers at the university would like to hear it, so please write accordingly.

Genre: Review

Angle: Approach this assignment from the angle of wanting to help people understand how to use this resource best. For example, if you feel that your resource has awkward hours, this is worth mentioning, but then your review should talk about how a student interested in this resource can best work around these hours (remember the constructive feedback aspect). Your review should never become an all-out attack, especially since you should be choosing a resource that you are somewhat familiar with or use successfully on a regular basis.

The Task: Construct a review of 750-1000 words that has a descriptive and enticing title, has an engaging introduction, explains aspects of the resource in informative and interesting ways, provides rich and vivid details, includes quoted or paraphrased material (if possible), includes anecdotes and graphics, and ends with distinct and appropriate conclusion.

Notes on Writing Your Review: If you are quoting materials in your review, make sure it is clear that you are borrowing someone else’s words—use quotation marks.

Reflection Guidelines:The purpose of the reflective letter is to give you an opportunity to reflect on your writing, your writing process, and how you could improve your writing and/or process. In your reflective letter, you should address the following questions:

- What is the purpose of your review and how have you attempted to achieve this purpose?

- How did your intended audience influence your decisions as you composed your review?

- What Student Learning Outcomes do you understand better after having completed this assignment? What in the assignment helped you deepen your understanding of them (write about at least three, and use specific examples from your paper)?

- What was easy about this assignment? What was difficult, and why?

Your review will be evaluated based on its title (5%), the introduction (5%), the rich description of your chosen resource (20%), the organization of your review (20%), the angle you offer that helps readers understand why this review is important to them (15%), the conclusion (5%), the style of the review (5%), the grammar and mechanics (5%) and, finally, your reflection (20%).

Notes

- For information about the required, 3-credit, graduate-level course that prepares our instructors to teach in the stretch/studio program, see Davila and Elder (2017) forthcoming in Composition Studies, fall 2017. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Adams, Peter, et. al. The Accelerated Learning Program: Throwing Open the Gates. Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 28, no. 2, Fall 2009, pp. 50-69.

Bartholomae, David. "Inventing the University." Cross-Talk in Comp Theory: A Reader, edited by Victor Villanueva, NCTE Press, 2003, pp. 623-53.

Bizzell, Patricia. Cognition, Convention, and Certainty: What We Need to Know about Writing. Cross-Talk in Comp Theory: A Reader, edited by Victor Villanueva, NCTE Press, 2003, pp. 387-411.

Canagarajah, A. Suresh. The Place of World Englishes in Composition: Pluralization Continued. CCC, vol. 57, no. 4, June 2006, pp. 586-619.

Davila, Bethany and Cristyn L. Elder. Stretch and Studio Composition: Creating a Culture of Support and Success for Developing Writers at a Hispanic Serving Institution. Composition Studies, vol. 45, no. 2, Fall 2017. Accepted May 8, 2015.

Gee, James P. "What Is Literacy?" Rewriting Literacy: Culture and the Discourse of the Other. Edited by Candace Mitchell and Kathleen Weiler, Begin & Garvey, 1992, pp. 3-11.

Glau, Gregory R. Stretch Courses, WPA-CompPile Research Bibliographies, No. 2. WPA-CompPile Research Bibliographies, 2010, pp. 1-4, http://comppile.org/wpa/bibliographies/Bib2/Glau.pdf.

Grego, Rhonda and Nancy Thompson. Repositioning Remediation: Renegotiating Composition’s Work in the Academy. CCC, vol. 47, no. 1, February 1996, pp. 62-84.

Horner, Bruce, et al. Opinion: Language Difference in Writing: Toward a Translingual Approach. College English, vol. 73, no. 3, Jan. 2011, pp. 303-21.

Matsuda, Paul Kei. The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition. College English, vol. 68, no. 6, July 2006, pp. 637-51.

Preto-Bay, Ann Maria and Kristine Hansen. Preparing for the Tipping Point: Designing Writing Programs to Meet the Needs of the Changing Population. WPA, vol. 30, no.1-2, Fall 2006, pp. 37-57.

Ryan, Camille. U.S. Census Bureau. Language Use in the United States: 2011. American Community Survey Reports, August 2013, https://www.census.gov/prod/2013pubs/acs-22.pdf.

Soliday, Mary, and Barbara Gleason. From Remediation to Enrichment: Evaluating a Mainstreaming Project. Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 16, no. 1, Spring 1997, pp. 64-78.

University of New Mexico Office of Institutional Analytics. Fall 2015 Official Enrollment Report Albuquerque Campus: As of Census Data, September 04, 2015. University of New Mexico, September 2015, http://oia.unm.edu/facts-and-figures/documents/Enrollment%20Reports/fall-15-oer.pdf.

Young, Vershawn A. Your Average Nigga: Performing Race, Literacy and Masculinity, Wayne State UP, 2007.

Stretch and Studio Composition at a Hispanic-Serving Institution from Composition Forum 35 (Spring 2017)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/35/new-mexico.php

© Copyright 2017 Bethany A. Davila and Cristyn L. Elder.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 35 table of contents.