Composition Forum 37, Fall 2017

http://compositionforum.com/issue/37/

Genre, Reflection, and Multimodality: Capturing Uptake in the Making

Abstract: Scholarship on metacognition in the composition classroom shows how asking students to create reflective texts can help cue, analyze, and assess transfer. By following the composition processes of 13 students doing a remixing assignment, this project examines how genre mediates reflection. I use Rhetorical Genre Studies’ conception of uptake—focusing on the selection process of choosing a genre and the eventual genre production—to examine students’ reflective practice within this assignment. Tracing the students’ uptake selection processes and comparing them to what students reflect about in their reflective texts reveals how reflection is mediated through genre. I argue that reflective practice should take place through a variety of genres throughout the composition process, rather than just retrospectively on the finished product. Asking students to do multi-genred reflective writing throughout the composition process could allow students to map their uptake selection processes more effectively when moving across multimodal genres.

Introduction

Within Composition Studies, there is a growing interest in how to best help students transfer knowledge across media and temporal boundaries, and metacognition has been recognized as a crucial practice in aiding students’ transfer (Beach; Beaufort, Writing in the World, College Writing and Beyond). Given the way metacognition can be practiced through reflection (Yancey et al), many scholars promote assigning reflective texts. In Reflection in the Writing Classroom, Kathy Yancey delineates three domains of reflection: reflection-in-action, or the “means of writing with text-in process”; constructive reflection, or the “generalizing and identity-formation processes that accumulate over time, with specific reference to writing and learning”; and perhaps the most common, reflection-in-presentation, or “formal reflective text written for an ‘other’ often in a rhetorical situation invoking assessment” (13). More recently, multimodal composition scholars argue for incorporating reflective texts alongside multimodal project production, in part for students to practice metacognition but also in response to the difficulty in assessing multimodal texts (Lutkewitte; McKee and DeVoss; Shipka, “Negotiating Difference”; Sorapure). Jody Shipka, in particular, advocates for these kinds of reflective texts, introducing an activity based framework in which students create visual depictions of their composition process (“Digital Mirrors”) and a mediated framework in which students write a Statement of Goals and Choices (Toward a Composition Made Whole). Reflective texts produced alongside multimodal projects might be considered reflection-in-action because they have the potential to capture reflection on students’ rhetorical choices as they are drafting the multimodal project, but also might be considered reflection-in-presentation because students might curate a narrative of their rhetorical choices for the teacher as a means of guiding assessment.

Using reflective texts to aid assessment of multimodal projects has become popular because of the difficulty of assessing multimodal texts. Yancey’s 2004 CCCC keynote, Made Not Only in Words: Composition in a New Key, which was later reprinted in CCC in the December 2004 issue, called for the field to take up multimodal composition in their teaching and consider how it might be assessed in their scholarship. As Yancey explained in another article, assessment practices traditionally used with writing-only texts could not be transferred unilaterally in multimodal contexts (Yancey, Looking for Sources), so assessment of multimodal student work has continued to be a topic of concern amongst teachers and scholars. Emerging multimodal scholarship called for teachers to use peer review, journaling, and student/teacher co-authored rubrics attuned to rhetorical considerations of specific projects (Borton and Huot). In 2009, Shipka called for more assessment strategies to be developed because there was a “dearth of scholarship devoted to the assessment of multimodal and new media texts” (Negotiating Difference 346), and those that were discussing assessment were largely focusing on how to assess a project where all students produced the same type of multimodal project (Sorapure; Zoetewey and Staggers). Shipka announced her framework of assessment: an extended reflective text called a Statement of Goals and Choices (SOGC), which seemingly builds upon Yancey’s reflection work. As such, some multimodal scholarship advocates adding companion reflective texts to multimodal projects as means of aiding assessment of the multimodal projects or as a space for students to do metacognitive rhetorical knowledge work (see, for example, DePalma; Reiss and Young; Shipka, Toward a Composition Made Whole).

Because the reflective texts serving as companion pieces to aid in multimodal project assessment are SOGCs or adaptations of those like artist’s statements, writer’s memos, or heads up statements, and tend to be done retrospectively, it is imperative that we become more critical about how these assigned reflective genres mediate the reflection that students do. This is especially true given the lofty goals of such assignments as doing transfer work. Cheryl Ball, who once assigned written reflections with multimodal work, no longer does because she sees the written reflection as a “school-based genre that doesn’t have any context outside of a particular writing class” (28). Though Ball’s students wrote convincing and detailed reflections, Ball saw them as a “mutt genre” (Wardle), which led her to see the reflective text as something that did not necessarily facilitate transfer.

Ball’s wariness about genres used to do reflective work is not new: in 1998 Yancey urged us to investigate the genres students enact to produce reflective work. She stated, “If the point, ultimately, of reflection is to encourage reflective writers, and if we expect those writers to work in various genres, then it might make sense to ask for more than one kind of reflective text, whether they be independent documents or within portfolios” (154). Here, Yancey puts forth the premise of my argument: we must be cognizant of the genres that mediate reflective practice because they shape students’ potential metacognitive practices. Yancey comments on this in Reflection in the Writing Classroom, announcing that “reflection is rhetorical” (12), a concept she and the other authors explore further in her 2016 edited collection A Rhetoric of Reflection. Claiming that “reflection is rhetorical” means that it typically emerges from a context, has an author with a purpose, and affects an audience. This is important for us to consider as composition teachers because, like Joddy Murray explains, “[reflection and self-assessment are] only effective as long as the writing teacher realizes that the reflections they are getting are also rhetorical” (187). The rhetorical nature of reflection makes it inherently entangled with ideologies, and therefore, as Kara Poe Alexander’s work on reflection in literacy narratives demonstrated, “we may in fact be asking [students] to perform particular subjectivities that they may or may not be prepared (or willing) to perform” (47). At a time when reflective texts are playing an increasingly important role in composition pedagogy, I join the chorus of voices asking us to recognize the ways in which reflective practice is rhetorical, mediated by genre, and steeped in ideology. Further, I push us to consider how genres mediate students’ articulations of reflective practice by documenting the effects reflective genres have on students’ self-selection of what to reflect about. I hope this recognition and awareness will allow us to strategically assign a variety of genres for reflective practice, encouraging different types of metacognitive work suited to our pedagogical goals.

To better understand how genres mediate reflective texts, I turn to “uptake,” a term used in Rhetorical Genre Studies (RGS) to explain the complicated selection process of creating and moving across genres. As I discuss in the next section, research on uptake has drawn attention to the complex factors that shape when, why, and how individuals take up genres. Given how many influential factors are at work in the uptake selection process, a single reflective text is likely unable to capture it. Reflective texts, especially those that are mono-modal and pre-determined, tend to provide constructed snapshots, presenting choice-making in static, stable ways instead of the ongoing, in-flux, and multi-variable entanglement of the composing process involved in uptake. Reflection-in-presentation texts, in particular, typically focus on the writer and their rhetorical choices in a particular writing situation, prompting the student-author into performing a narrative of success. The performative articulation of reflection can provide glimpses of fixed moments, which is problematic for capturing metacognition about selection processes in action. Tracing uptakes allows insight into “how novice writers select for themselves the relevant genre for a new writing situation” (Rounsaville). It can provide insight into students’ reflective practice and how multiplex forces in their composition process are reflected upon (or not) in their reflective texts. To better understand how genres mediate reflective work, I conducted a pilot study that documented thirteen students’ composition processes, comparing their reported uptake selection process to what was captured in reflective texts of various genres. This pilot study can provide insight into the types of choices that students are making when composing, which of those choices reflective texts capture (and which they do not), and how we might want to change our pedagogy accordingly.

Theoretical Underpinnings: What is Uptake?

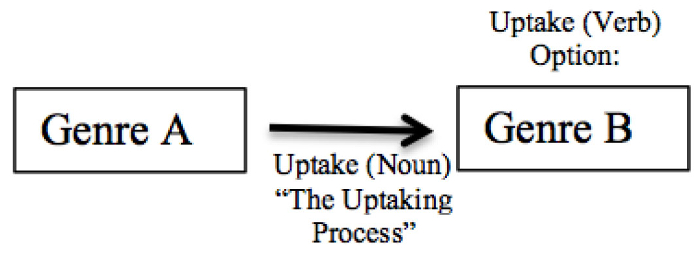

When a genre is produced, uptake occurs. Uptake is integral in our understanding of genre knowledge because uptake explains why producing a genre is not a simple cause and effect relationship (Freadman), as depicted in Figure 1. Despite its usefulness as a concept, the word “uptake” can be difficult to conceptualize because scholars have used it to mean a variety of different things. Dylan Dryer, for instance, distinguished five different ways that uptake has been used: uptake artifacts, the produced genre; uptake enactment, or the repurposing of a genre; uptake affordances, or the ways that scholars have discussed the affordances of a produced genre; uptake capture, or the processes of uptake; and uptake residue, lasting effects from previous selection processes on the current selection process.

Figure 1. Cause and Effect Understanding of Uptake.

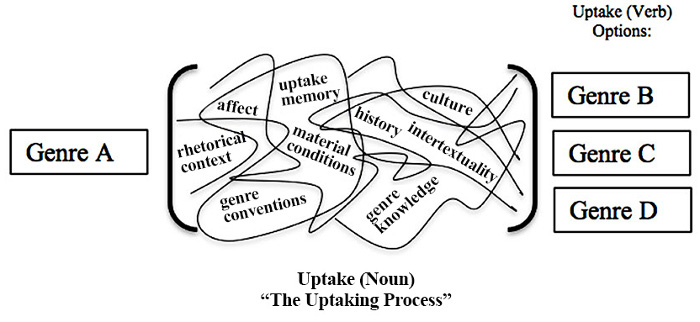

Figure 2. Depiction of Uptake.

To simplify the explanation of these various uses of uptake, I will describe two umbrella categories for the various ways that it has been used as a verb—or Dryer’s distinction of uptake artifacts, enactments, and affordances—and as a noun—or Dryer’s distinction of uptake capture and residue. Uptake typically has been thought of as the verb: the perlocution of the genre. It is seen as the active effect, as in “my student had the uptake of creating a brochure when asked to remix her assignment.” Yet, uptake also can be thought of as a noun—the uptaking process—or the negotiations involved in the possibility of becoming. It is in this—for lack of a better word—space that a myriad of factors are negotiated: material conditions, medium, history, culture, uptake memory, rhetorical context, genre conventions, previous genre knowledge, intertextual generic relationships, affect of the social agent, and so many more than can be named here (Bastian; Bawarshi; Dryer; Emmons; Reiff and Bawarshi). These factors layer together to present different trajectories for genre uptakes, symbolized by the swirling lines in Figure 2 to represent the complicated and convoluted negotiation of factors that shape what gets taken up, how, and why. Some scholars theorize this negotiation of the selection process of uptake in a human-centric way (Rounsaville; Tachino). For instance, as Bastian explains, “uptake, ultimately, depends on the act of selection, which, as these scholars point out, relies on people and their action” (emphasis added). In saying that uptake “relies on people,” Bastian puts the control of uptake in the hands of the social agent. To a degree, this human-centered selection process is accurate: social agents deploy their knowledges to navigate the selection process, insofar as it is in their control. Yet, some factors, particularly material conditions, are not human-controlled and channel uptakes in ways that are unintended by the social agent (Bawarshi). Like Spinuzzi demonstrated in his case study of Telecorp, agency is distributed amongst a variety of materials and humans within activity systems, or “the complex relations within and between genre systems” (Bawarshi and Reiff 102). In the school setting, for instance, the amount of time available for a student to work on an assignment or the fact that their computer malfunctions are uncontrollable factors to the social agent but affect the uptake. Thus, a variety of factors, both human-controlled and otherwise, work together within the uptake process and can result in a variety of uptakes.

Multimodal scholars, particularly Shipka, have recommended reflective texts to prompt consideration of materiality’s effect on rhetorical choices, such that students account for space, time, modalities, bodily actions, technological choices, and social interactions. My use of uptake in this study further situates this pilot study to understand the dynamic, complex uptake processes that are mediated through various reflective genres. Using the theoretical framework of uptake to compare what students name as uptake selection factors, or considerations negotiated in the creation of a project, to what decisions are reflected on (or not) in their corresponding reflective texts can illuminate how genres mediate reflection. The results of this pilot study indicate the affordances of various reflection genres, all of which allow students to map their uptake selection processes but do so in different ways. Because all the reflective texts collected in this study were produced upon completion of their genre remix assignment, there is a risk of students manufacturing maps of their composition process and selecting only pieces of the complex uptake processes they have just navigated. Targeted questions and triangulation of reflective texts mitigate this risk, but the findings also encourage the use of reflection-in-action texts in the classroom and a shift in future reflection research methodologies.

Context and Methodology

The context of this pilot study was a first year composition class, a class that fulfilled the composition requirement at a large research university. One class session per week was scheduled in a computer lab, and the other was in a traditional classroom. I taught this class twice a week in Spring 2015 to a total of 23 students. Because I am the data collector and the teacher in this research context, my position gives me insight into the curriculum and a rapport with students, both of which could aid data collection. Yet, this position as a researcher and teacher could change what students felt comfortable reporting. I mitigated these potential drawbacks by assuring students that participating in the study would not impact their grade in the course and informing them all recorded data would remain anonymous when reported.

Our particular first year composition course also had a service-learning requirement, so each student volunteered consistently with their choice of a community partner, which included five different non-profit organizations working to alleviate poverty and homelessness in the city in which our university is located.{1} We focused on multimodal genre analysis and multimodal genre production because students were analyzing and creating texts for their community partner, and most of those texts were public-facing genres that employed multiple modes.{2} For the purposes of this pilot study, I focus my data collection on one assignment in our class: a re-mix assignment (see, for example, Dubisar and Palmeri; Johnson-Eiola and Selber; Ray; Rice). The prompt for this assignment (provided in Appendix 1) asks students to do a remix and a writer’s memo about their composition process. It presents students with two options for their original artifact: 1) their Major Paper 1 (MP1), an argument paper about the rhetorical effectiveness of their community partner that students had completed in the first half of the course, or 2) one of the sources used as evidence in their MP1. Once the students picked the artifact of their choice, the prompt requests that they recast that artifact into a new “multimodal creation” of their choice, with a purpose and audience different from the original artifact.

To be eligible for this pilot study, each participant had to be a member of the class, consent to the research methodology, and complete all aspects of the data collection. Thirteen students participated in the study: 7 men and 6 women, all of whom were 18-20 years of age and first- or second-year students. The students were selected based on interest in being involved in the study, along with eligibility of being in the study. Of the thirteen students, one student was an intended humanities major, three were intended engineering majors, four were intended social science majors, and five were intended science/math majors.

In this pilot study, I traced what Anne Freadman calls “intergeneric uptakes”, or the relationships between texts, which in this research context consisted of: the assignment prompt, a summary of the student’s free write about the initial reaction to the prompt, the original source that was remixed, the writer’s report on their favorite idea from the in-class group brainstorming of how to remix a course text, the remixed artifact produced in response to the prompt, the writer’s memo about their choices in composing the artifact, the comic about the composing process of that artifact, and the survey about their composition process (see the survey, Appendix 2).{3} I chose to focus on intergeneric uptakes because they allowed me to understand what reflective texts captured. Reflection is a cognitive activity, but evidence of it can be found in texts students produce. I studied this series of intergeneric uptakes to better understand the role of genre in reflective activity and articulation.

I modeled my methodology after Bastian’s study of individual uptake, triangulating data gathered from various sources: observation of classroom activities and three reflective texts—a writer’s memo, a survey, and a comic—all of which were selected because they have all been used in the composition classroom to articulate students’ reflective practice. The writer’s memo and comic were inspired largely by Shipka’s work because she has asked students to write a Statement of Goals and Choices and create visual representations of their composition processes. The survey was inspired by Yancey’s choice to interview students about their composition processes, making the interview function like a reflective text. Kevin Roozen, more recently, has argued that interviews can indeed be considered reflective texts. The survey format used here was done for convenience because it was given as a homework assignment, but worked in similar ways: to use targeted questions and responses to those questions in order to function as a reflective text. I chose to use the combination of a writer’s memo, comic, and surveys after students had turned in their final project because then they were one type of reflection: reflection-in-presentation. By only choosing one type of reflection, I could narrow the scope of this study to focus on the genres used to do reflection-in-presentation, which is arguably the most researched and assigned type of reflection (see the types of texts studied in Yancey, A Rhetoric of Reflection, for example). The genres I chose to study in this pilot study also utilize a range of modalities for communication—linguistic and visual—to initiate investigation into how modal affordances of genres mediate reflection articulation, but still limit the scope of the modalities explored, which is important given the nature of this pilot study.

To conduct this research, I first observed the interaction students had with understanding the constructed exigency for the assignment. Both my verbal description of the assignment and the prompt of this assignment were specifically tailored not to use the word “genre” anywhere because I wanted students to decide whether they would pick generic remixes or not. Students next completed a free write responding to their initial reactions of how they would uptake the prompt. The survey later asked them to summarize what was in their initial free write. Then, students were tasked to get in groups of three to four participants to brainstorm 30 hypothetical remixes of one of our course texts. After the activity, all students named their favorite idea for remixing the course text, which I recorded. With their assignment, students were tasked with creating a written writer’s memo. Two days after the remix assignment and writer’s memo were turned-in, students composed a hand-drawn comic documenting their uptake selections for the assignment. Finally, students completed a survey using Bastian’s survey as a guide for what information would be important in capturing uptake selection processes—student disposition, interpretation of the assignment, and genre knowledge—while also including questions about non-human factors that contributed to their uptake process, which helped overcome any potential human-centric focus of uptake selection factors in what students were asked to reflect upon (See Appendix 2). I used the observations and the survey to gain a broad understanding of each student’s uptake selection process, which is provided in the section entitled Uptake Selection Process.

Then, after all the documents were gathered, I conducted qualitative textual analysis on all of the reflective texts—the writer’s memos, the comics, and the survey—all of which is detailed in a later section, Trying to Capture Uptake in the Making: How Genres Mediate Reflection. I began by creating a table that overviewed key moments in students’ composition process: original artifact, initial idea, favorite brainstorm idea, and final project. The original artifact selected, initial idea for the remix that students wrote about originally in a free write, and the genre of the final remix were all disclosed in the survey. The favorite brainstorm idea was observed and recorded when students shared them during class. To find out what factors influenced these decisions throughout the students’ composition processes, I used grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss) to develop a coding schema for uptake selection factors. I selected this methodology because of the nature of this study: uptake is not a closed set variable, and during the time this project was conducted, uptake did not have agreed upon coding variables. Therefore, I used a methodology that would allow all potential variables to emerge from the data. All of the categories represented in the tables below materialized from student survey responses, which asked students questions about influential factors in their process. To do the coding, I first read through the data to find selection factors that they named, then created categories that were representative of those factors, and finally tallied the instances of each category across all students. For instance, when asked about what influenced their final decision of what to create, one student said, “Time and experience were both large factors in the decision process of what to create for SA2” and another said, “I think time, or lack there of, had the biggest influence on my deciding to create a meme… Other than time, previous experience played a roll in my deciding to create a meme.” Both of these students were recorded as having “time” and “previous genre experience” as uptake selection factors. Even though this is a small sample size of thirteen and therefore is not generalizable to larger populations, the pilot data works to show how we might investigate uptake selection processes and use that investigation to better understand what kind of metacognitive work is done in various reflective texts.

Uptake Selection Factors

In what follows, I first provide an overview of the data, which suggest that, overall, student interpretation of the prompt, the modes of the original text, students’ comfort with genres, and the mode of assignment submission are instrumental in students’ ultimately remixed texts. Then I investigate the perceived uptake factors in play throughout the composition process, demonstrating how these factors are constantly in flux and time-specific. The last part of this section pulls together all of the data, using the snapshots to construct an overall narrative of student uptake and how that relates to their reflective texts.

The assignment itself explained that students needed to either take their argument paper or a source used in their argument paper and then remix that genre to a new “multimodal creation.” I purposefully did not use “genre” in referring to what students would create because I wanted students to think more broadly about the potential uptakes of this assignment. Due to the prompt’s ambiguous wording along with my own vague description of possible uptakes of this assignment, students interpreted this prompt in a variety of ways. According to survey responses, six students of the 13 saw the purpose of the assignment as creating a multimodal project with a similar purpose to the original artifact. This is likely because of the focus on multimodal composition in the class, along with the use of “multimodal creation” in the prompt. Only two students actually named the purpose of the assignment a “remix.” The remaining three students all had unique interpretations: one saw it as a practice for their future Major Project 2, which asked them to create something for the organization; another student saw the prompt as asking them to create something for the community partner they worked with for their service learning component of our course; and the last student saw it as a way to learn more about the social issue that their community partner aimed to alleviate. This shows the complexity of uptake processes: students have a range of interpretations about the purpose of the assignment.

The interpretation of the prompt was relatively student-centered. In survey responses, students documented how they felt agency in this assignment and that they felt safe in making their projects because the prompt seemed open to interpretation and had low stakes, given its status of a “short assignment” rather than a “major paper or project”.{4} Many students, like Mike,{5} document that the guidelines for this prompt were not overtly prescriptive; it was a “fun and easy” assignment. Ken recognizes that he felt comfortable remixing his work because he knew I expected it to have a “limited” scope given its status as a “short assignment.” Four students admitted that they were not really concerned about my goals of the assignment but instead were more focused on what they wanted to create. The remaining nine students who were concerned with “what the teacher wanted” still saw this as an assignment that invited a more open-ended response. As Dan explained in his survey response, “I figured that all you were looking for in this assignment was just a remix of a genre. I think I gave you exactly that. I did not feel limited to any type of genre, and so I was allowed to be creative.” In saying that he “gave [me] exactly [what I wanted],” Dan clearly states that one of the uptake selection process features was his disposition towards me as a teacher. Yet, that is not the only, or main, factor. The type of assignment influenced his uptake process: “If this was a major paper or a large assignment I would not have been so bold. The leeway of this being a short assignment allowed me to experiment and try new things. I also lack very many other talents, especially with visual art. I decided that although I am not very good at it, poetry is something that anybody could write. Speaking is something anybody could do.” It appears from the survey responses that students saw this assignment as open-ended and creative, an assignment that deviated from their expectations of what is “normal.” Given this perception of the assignment, along with its status as a “short assignment,” students felt more comfortable engaging in play during their uptake selection process.

To better understand more factors at play than students’ interpretation of the prompt, it is important to see their overall uptakes, which I followed using one of the reflective texts: the students’ survey responses. With these survey responses, I mapped the surface level trajectories of students’ uptakes, which are detailed below in Table 1. This surface level mapping is useful because it provides an overview of the composition processes, which can be compared to what students reflected on in two other reflective texts—the writer’s memos and comics—giving insight into how genres can mediate reflection. The data from Table 1 demonstrates that the students’ trajectories throughout their composition processes are more complex than what can be captured in a single-genre reflection. It suggests that multiple reflection assignments throughout the composition process might be better suited than waiting to do a retroactive reflective assignment. Also, it is important to consider what kinds of genres might work together to capture the incredibly complicated, nuanced decision-making that happens throughout the uptake selection process. Exploring students’ composition process has the added benefit of illuminating common uptake trends, which can inform pedagogy, particularly of remixing projects.

Table 1. Composition Process Overview.

|

Name of Student |

Original Artifact Chosen to Remix |

Initial Idea |

Favorite Brainstorm Idea |

Final Project |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ari |

MP1 |

Spoken Word Poetry |

Poster Campaign (on campus) |

Tumblr |

|

Brett |

Photo |

Rap (or something artistic) |

Theatre Performance |

Meme |

|

Charlie |

MP1 |

PowerPoint |

Cake |

Short Story |

|

Dan |

Photo |

Spoken Word Poetry |

Rap |

Spoken Word Poetry |

|

Eric |

All Artifacts |

Video |

Mixed Tape |

Brochure |

|

Fiona |

MP1 |

Children’s Book |

Theatre Performance |

Flyer |

|

Gary |

Quote from Website |

T-shirt |

T-shirt (wear on campus) |

Poem |

|

Hailey |

Banner |

Video |

FB Challenge |

FB Challenge |

|

Isabelle |

All Artifacts |

|

Memes |

|

|

Juliana |

Logo |

Spoken Word Poetry |

Workout Routine |

Photo Essay |

|

Ken |

MP1 |

Logo |

Interviews |

Poem |

|

Lilly |

Photo |

Lollipop |

Public Awareness Event |

Taffy |

|

Mike |

Mission Statement |

Poem |

Displayed Art |

Poem |

The table above provides an overview of the pilot study students’ composition processes. It uses a color-coding schema to indicate if there were similar primary genres between the original artifact and the final project. Green represents projects that completely changed modalities, purple represents projects that added a new modality, and blue represents similar modes and primary genres between the original artifact and the final project. Bolding is also used to emphasize if a potential uptake selection repeats itself within the timeline established in the table. Italics indicate that students reported in the survey that the brainstorm activity that they did in class was helpful in their eventual final project uptake.

First, this table can give insight into how students chose to remix projects: most students made relatively “safe choices.” Eight of the thirteen students, who were color coded in blue, used the same mode(s) of their original artifact in their final project. Brett, color-coded in purple to indicate that he added a new modality, took the primary genre of a photo and added an utterance to make the secondary genre of a meme. In all of the reflective texts—the writer’s memo, the comic, and the survey—students did not reflect on why they decided to remix their projects to genres that used similar modes of communication and thus the same modal affordances. These types of “safe choices” were not just made with the modalities utilized in final projects, but were also present in looking at what kinds of projects were created. All students created a text that could be identified easily as a genre, which is interesting because the prompt strategically avoided the word “genre,” and remixing projects lend themselves just as well to hybrid or mixed generic uptakes.

Another factor that was integral in the types of genres chosen was the medium used. All of the students’ final projects, except Lilly’s, used a digital medium and were produced with a computer. This could be because this assignment, along with all assignments in this course, was submitted online. I had specifically instructed students that they were welcome to turn in three-dimensional objects. To submit, they would need to take a picture of their multimodal creation and upload that to our course management system, and then they would bring the object to class. Only Lilly took up a kind of project that responded to this suggestion, raising a question—that not one student reflected upon in any of the reflective texts—about the seemingly pre-conditioned uptake, under the given circumstance and conditions, of a computer-generated text. This seems to suggest that reflections can focus merely on the individual author and their choices rather than on the material considerations, which appear to be unconscious or at the very least, not worth mentioning. Perhaps students do not see technological considerations as part of their uptake processes, which limits their reflections.

Table 1 also gives a snapshot of various points throughout the students’ uptake selection processes. Given the trajectory of students’ uptakes, it is clear that having a consistent uptake plan is uncommon with these students: none of the thirteen students have the same intended final project across all steps of the composition process. This suggests that it is important to ask students throughout the composition process to produce reflective texts. Utilizing metacognitive work throughout could allow students to think through how and why factors change over time—something that likely was not practiced amongst these students because of when the reflective texts were produced in this study. The free write and the brainstorming were done at the beginning of their composition process, and the survey, comic, and writer’s memo were completed at the end.

Asking students to produce reflective texts throughout the process could help students reflect upon why and how their plan shifts over time. For example, three of the thirteen students use their initial idea of what they would like to create as what they ultimately create for the final project, but even they oscillate to another uptake plan in one recorded instance: the brainstorm activity. Also, the italics on the table indicate that seven of the students saw the brainstorming as instrumental in deciding what they ultimately produced. Yet of those seven, only one used her reported favorite brainstorming idea as the final uptake, so it is clear that many students saw thinking about the range of possibilities useful but did not make their favorite brainstorming idea their final uptake. In fact, one student, Mike, saw the brainstorming as helpful, but he reverted back to his original idea from the free write (a poem) for his final uptake. The evidence for why students shifted final uptake plans throughout their uptake selection process is not clear in students’ writer’s memo. This is not because they are unable to do reflective work upon their entire composition processes: students just do this in the survey, a genre that allows for targeted question and response work to be done. However, the writer’s memo, which students used as a means of justifying their rhetorical choices, did not usually document the composition process longitudinally but rather focused on uptake factors within the final project. If we want students to reflect on the whole process, it is imperative, just as Yancey (Reflection) reminds us, that we consider the questions we are asking in our reflection prompts and the timing in which we do them. In only asking students to consider the rhetorical choices of their project, they tend to create a success narrative, only pointing out how the choices in their final project are rhetorically effective rather than examining potential failures or acknowledging how material conditions like ease of composing, time, and genre knowledge played a role in their decision making. If we want students to reflect on these types of choices, then we must both ask the questions in our own writing prompts and consider using a genre that encourages students to construct something other than an argument about their work.

The survey results of the thirteen students also were used to distinguish some of the uptake factors at play in deciding what project to do. The survey asked students to list reasons for the intended initial idea and for the final project that they chose. Using grounded theory (Glaser and Strauss), I developed codes to capture different uptake factors, or factors at play when students navigated the uptake selection space. Of course, given that these are factors self-reported from students, they surely are not all of the factors present in the selection process; they are just the ones that students were aware of, remembered, and reported. In Table 2, it is clear that there are a variety of factors: students’ disposition, genre familiarity, intended purpose, and material concerns. Bolding in this table is done to draw attention to uptake factors that most dramatically change from the initial idea to the final idea.

Table 2. Uptake Factors.

|

Uptake Influencing Factors |

For Initial Idea Frequency/Participants |

For Final Idea Frequency/Participants |

|---|---|---|

|

Easy |

0 |

4 |

|

Fun |

4 |

3 |

|

Genre Knowledge |

0 |

2 |

|

Money |

0 |

2 |

|

No reason stated |

1 |

0 |

|

Not being good at another thing |

0 |

1 |

|

Previous Experience |

3 |

4 |

|

Something about the original artifact |

2 |

1 |

|

Tailored for intended purpose |

1 |

3 |

|

Time |

0 |

6 |

|

Trying something new |

2 |

3 |

|

Wanting to help the organization |

3 |

0 |

|

Wanting to gain mastery |

1 |

0 |

Table 2 demonstrates that uptake selection process factors are not static: they are in flux throughout the composition process. It seems, then, that we should potentially vary the times we ask students to produce reflective texts; if we only wait until the end of the process, they might not reflect on this change in uptake factors because they may only remember the most recent factors. The bolding on this table indicates the factors that shift significantly over time, and it is clear that there is one uptake factor that is initially important to some students but then is not discussed when asking students about their final uptakes: wanting to help the organization with which they do their service learning. Three students—Charlie, Eric, and Fiona—had a desire to create an artifact that helped the organization when brainstorming their first ideas for this assignment. Even though none of them produced their initial idea for their final project, they also did not name a concern for what their community project needed as an uptake factor again at any other point in their composition process. Fiona removes the factor of helping the organization all together for the final uptake because she re-read the prompt after her initial idea and interpreted it as a genre re-mix, not intended to help the organization, which caused her to re-interpret her MP1 (survey). For both Eric and Charlie, this is likely because they re-interpreted their specific way of helping the community developed in their initial day to be the “purpose” in their final project. When responding to what influenced his uptake of his final project, Eric stated,

I ended up creating a brochure instead with similar purposes as the video. The brochure is basically the same thing but in a different genre. I also made the topic a bit more broad. I advertised [my community partner] as a whole. I also thought about how effective this project would be if I were to actually put it in effect…Also thinking about who the main audience is, it wouldn't make sense to create a video. How would most people who have financial problems have the resources to view an advertisement that requires technology? A brochure seemed more practical if this was for an actual real cause. (Survey)

In this description, Eric made it clear that his eventual uptake is about better achieving his purpose—along with some material concerns—and this shows how he has narrowed his original idea of helping the organization to be a more specific purpose.

Four new uptake factors occurred when students considered their final uptake: genre knowledge, money, easiness, and time. Genre knowledge is a rhetorical and material consideration. Money, easiness, and time seem to be more about the material considerations of the project, considerations that would be fruitful to reflect over in order to transfer this knowledge to new composing contexts. This kind of reflection—how knowledge, disposition, real world issues affect the composition—is not always going to be welcome in a reflective text, particularly when the genre picked has a purpose of aiding teachers in assessment. Students explained that they realized their project would not be feasible given honest assessments of themselves as learners in this particular rhetorical situation. Brett said, “I believe if I didn't have a bad habit of procrastinating then I would have created the rap” (Survey). In this excerpt, Brett acknowledged that his disposition, combined with the due date, create a trajectory that is somewhat out of his control. Gary discussed how factors outside of his control also influence his project uptake: “I was originally contemplating creating a T-shirt but I didn't want to spend the money, plus it would have taken a week to get here” (Survey). Both Brett’s and Gary’s insight work to confirm the theoretical understanding that uptake can be influenced by factors uncontrollable from the social agent. Students were not as apt to reflect upon these material considerations in their writer’s memo, which targets rhetorical considerations, whereas the survey prompts reflection on these material factors in their decision-making.

In Table 3, all of the data collected from the survey is displayed such that it is possible to trace the uptake of the students from when they received the prompt to when the final project was turned in to me. Two uptake factors were largely consistent across the students: disposition and enjoyment. All students except Charlie self-identified as creative students (despite none of them being intended art majors), and all students except Hailey, who claimed that she wished she had more guidance, reported on enjoying the assignment. The vast majority of the students changed their uptake plan each of the steps along the way. These changes in uptake plan were a result of a variety of uptake factors that differed from student to student.

Table 3. Uptake Overview.

|

Name |

Disposition |

Prompt |

Original Artifact |

Initial Idea |

Initial Idea Factors |

Favorite Brainstorm Idea |

Final Idea Factors |

Final Project |

Enjoyment |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Ari |

Creative |

Multimodal, Student’s Choice |

MP1 |

Spoken Word |

Fun, Personal Enjoyment |

Poster Campaign (on campus) |

Time |

Tumblr |

Yes |

|

Brett |

Creative |

Multimodal |

Photo |

Rap |

Fun |

Theatre Performance |

Previous genre knowledge, Time |

Meme |

Yes |

|

Charlie |

Writer |

Student’s Choice |

MP1 |

PowerPoint |

Helping the CP |

Cake |

Better for achieving intended purpose |

Short Story |

Yes |

|

Dan |

Creative |

Remix |

Photo |

Spoken Word |

Something about the original artifact, Personal Enjoyment |

Rap |

Trying something new, Not being good at another thing |

Spoken Word |

Yes |

|

Eric |

Creative |

Preparation for MP2 |

All Artifacts |

Video |

Helping the CP |

Mixed Tape |

Easy, Time |

Brochure |

Yes |

|

Fiona |

Creative |

Create for their CP{6} |

MP1 |

Children’s Book |

Helping the CP |

Theatre Performance |

Personal Enjoyment |

Flyer |

Yes |

|

Gary |

Creative |

Student’s Choice |

Quote from Website |

T-shirt |

No reason stated |

T-shirt (wear on campus) |

Easy, Money, Time |

Poem |

Yes |

|

Hailey |

Creative |

Remix |

Banner |

Video |

No reason stated |

FB Challenge |

Easy, Personal enjoyment |

FB Challenge |

No |

|

Isabelle |

Creative |

Student’s Choice |

All Artifacts |

|

Gaining mastery of genre |

Memes |

Easy, Personal Enjoyment |

|

Yes |

|

Juliana |

Creative |

Multimodal |

Logo |

Spoken Word |

Fun, Personal Enjoyment |

Workout Routine |

Fun, Personal Enjoyment, Money, Time |

Photo Essay |

Yes |

|

Ken |

Creative |

Multimodal |

MP1 |

Logo |

Trying something new |

Interviews |

Trying something new, Time |

Poem |

Yes |

|

Lilly |

Creative |

Multimodal, Learn about social issue |

Photo |

Lollipop |

Something about the original |

Public Awareness Event |

Better for achieving intended purpose |

Candy Making |

Yes |

|

Mike |

Creative |

Multimodal |

Mission Statement |

Poem |

Fun, Try something new |

Displayed Art |

Fun, Trying something new |

Poem |

Yes |

The fluctuating uptake plans and varying uptake factors were influenced from student interpretations of the prompt, which varied widely. Five students saw the prompt as asking them to create something multimodal, four students saw the prompt as asking them to create whatever they wanted, and only two saw the project as a remixing. The interpretation of the prompt—or re-interpretation as discussed earlier in the case of Fiona—led to different uptake factors. Because all of the students picked generic uptakes and most of the students used the same modalities as their original artifact, it seems that original genres do in fact guide students’ uptakes. Starting with genres made it less likely for students to consider hybrid genres as final uptakes. For all students except Lilly, the original genre limited the types of genres they considered: genres that used linguistic and/or visual modalities, all of which could be produced digitally. None of the students reflected on why they did not consider non-conforming or hybrid generic uptakes, despite them discussing why they chose that specific genre to achieve their purpose. For some students, they began with considering which artifact they would like to remix and then their uptake factors changed based on that. Lilly, for instance, chose a picture of a child with a lollipop at her community partner, which was a food bank, and thus re-mixed the artifact to be candy she created with ingredients from the food bank. Other students began with what they wanted their final project to do rather than the original artifact, and their purpose shaped what uptake features they considered. For example, two of the students, Eric and Isabelle, combined a multitude of artifacts (which was, in fact, not “allowed” by the prompt) because of their intended purpose. These examples work together to show the dynamic nature of uptake selection processes. Uptake selection factors vary depending on the students’ dispositions and goals, material considerations, and the timing within the composition process. Understanding what students consider in reflective texts, why they make those considerations, and how they articulate them in reflective texts can help illuminate the ways genre plays a role in students’ reflective practices.

Trying to Capture Uptake in the Making: How Genres Mediate Reflection

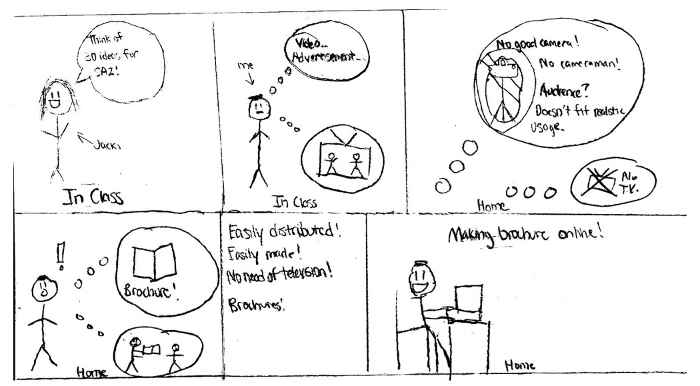

Figure 3. Eric’s Comic.

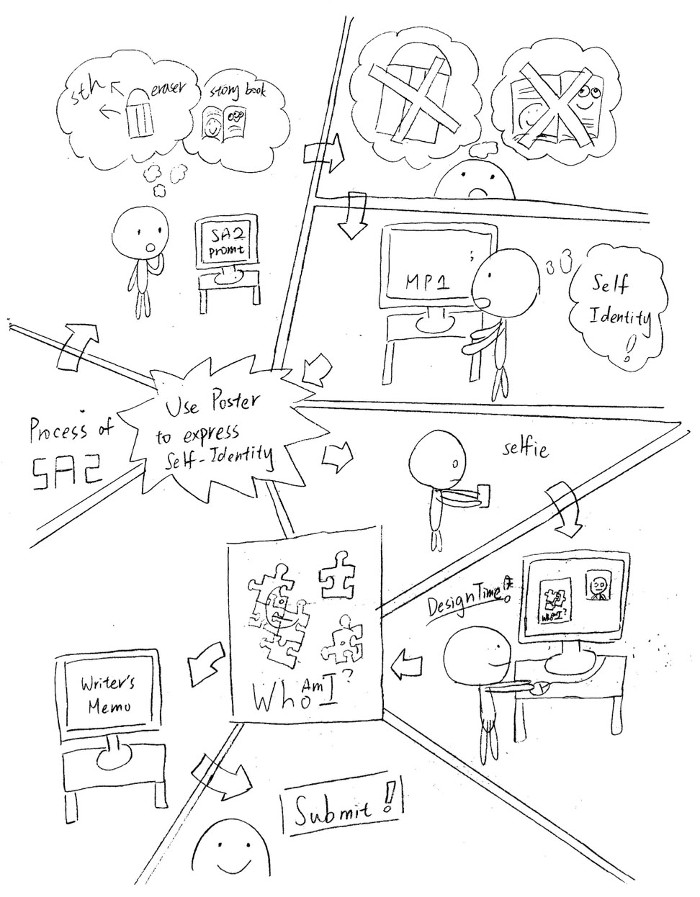

As the survey data suggested in the previous section, student text production is not as simple as them reading the prompt and deciding what to do; students’ plans shift throughout the uptake selection process depending on outside factors, like materials available and time, and internal factors, like project goals, genre knowledge, and student dispositions. Though students were capable of recounting choices made throughout their composition processes in the survey, all of the writer’s memos focused solely on the choices made in the composing of the final project. The surveys, on the other hand, tended to articulate reflection on the entire processes. For instance, Eric had reflected thoroughly about his final choice of a brochure. Eric indicated in his writer’s memo that the audience of his brochure is future members of his community partner, and his “intended purpose is to inform people in poverty and hunger that [my community partner] is a place to get help.” Because Eric was so clear on his purpose and his audience, he could dissect his design choices concretely. He wrote in his writers memo, “Brochures with a lot of writing may seem unappealing to many due to long readings. Pictures help the audience visualize what the brochure is saying with short sentences guiding them. Especially since many of the people reading are not first-language English speakers, pictures speak out better to this audience” (Writer’s Memo). This detailed reflection allows Eric to practice the work of dissecting his own design choices in the final product, but he does not use this genre to reflect upon why he picked a brochure itself. In his comic, which is captured in Figure 3, he does the important work of reflecting on uptake selection factors that occurred throughout his composition process. He considers the role of classroom activity of brainstorming initial ideas for how to respond to this prompt, along with material conditions like technology and time into his eventual choice of the brochure. This is in part because of the genre of the reflection: comics tend to do the work of telling stories, and Eric took up that generic purpose in his reflection. Writer’s memos tend to record, but they usually do so for the sake of aiding in assessment of the final product, which appears to have influenced the scope of the reflection provided.

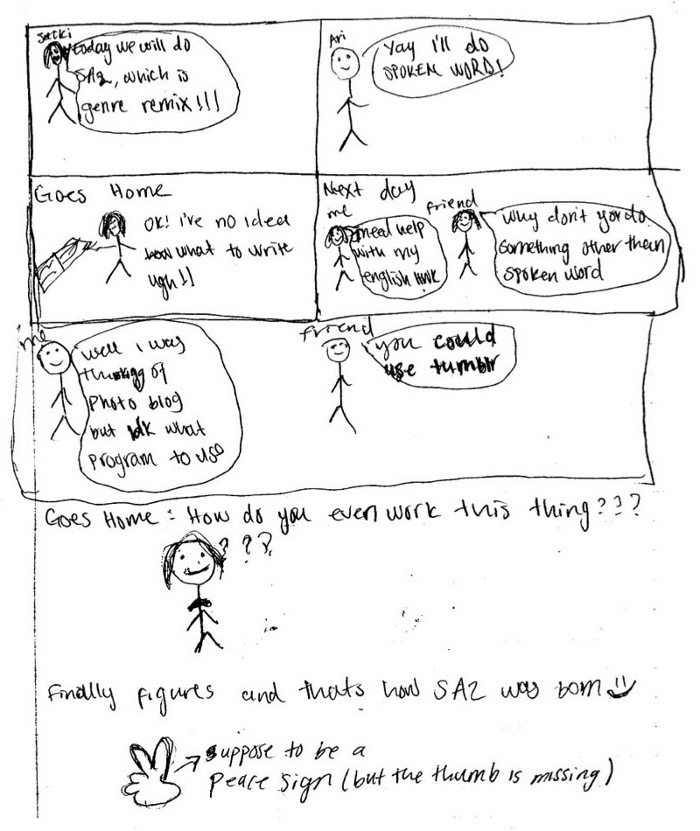

Figure 4. Ari’s Comic.

Likewise, Ari reflects upon her entire composition process in her comic, including moments not discussed in her writer’s memo. The comic, with each frame utlilizing visual and linguistic modalities, appears to encourage a holistic narrative of the composition processes. According to her comic, which is seen in Figure 4, Ari initially planned on a spoken word project and still intended on doing that project, but writer’s block deterred her from doing so. Ari ultimately chose tumblr, a genre she had never used before, based on a suggestion by her friend. In her writer’s memo, Ari neglected to reflect on why she chose the order of the artifacts in the tumblr post. This is likely because, in the survey, Ari explained how unfamiliarity with the genre made her unaware that she would not be able to change the order of her posts once she posted them. The low stakes nature of the survey, along with its evaluative approach, seems to have influenced what Ari was willing to disclose and reflect upon within that text. The genre of the writer’s memo, on the other hand, has the potential to mediate reflection such that authors focus on the finished project, crafting their reflection into a narrative of success, and therefore create an argument justifying the rhetorical effectiveness of the piece.

Figure 5. Fiona’s Comic.

Similarly, in her writer’s memo, Fiona only focused on the rhetorical choices within her final project. She wrote, “The background color is black which constructs a mysterious consciousness and facilitates the audience to think about who they are and the issue. The text is white, which is a strong contrast to the black background and draws the audience’s attention. The font is typical and conservative but the organization of the words make a point” (Writer’s Memo). In this writer’s memo, Fiona did a good job of being clear about what choices she is making, but she vaguely reflects on what the rhetorical purpose of those choices are. Nowhere in her writer’s memo did she name her intended audience—despite using the term throughout—and this made it more difficult for Fiona to be metacognitive about her work. It was not until I viewed her comic (Figure 5) that it became clear how she saw this assignment as a remix and thus changed her plans in a way that made her purpose less clear to herself, and later, me. In the survey, Fiona clarified, “I found that I should choose the sources from [my community paper] or from my MP1, but neither of my previous ideas are from [my community partner] or my MP1. Hence, I decided to use my MP1 as the original source, which is about self-identity. I have abundant experience and skills of digital image production, so I decided to make a poster, which is an effective media for conveying messages” (Survey).{7} In the survey, it is clear that Fiona shifted her purpose from doing something for the organization to just responding to the prompt. Interestingly, the comic captures this information rather than the writer’s memo. It seems comics mediated reflection such that Fiona told her whole story, from her initial ideas, to what she decided upon, and finally the decision-making she engaged once she settled on her final idea. The play she engages in with the splintered frames on her comic keeps the final project as the central focus, which she signals by its central location and zig-zag thought bubble that surrounds the text. Her arrows between frames show the connections Fiona makes between each moment she reflects upon, and how those moments culminate in her final decision of the poster. The arrows then show how this decision leads to further rhetorical choices within the project. The genre of the comic, and her play with genre of conventions, gave Fiona the space to reflect on her composition process longitudinally, and therefore prompted reflection on more of the composition process rather than only on the finished product, which suggests that reflective texts should vary genres and modalities.

Figure 6. Isabelle’s Comic.

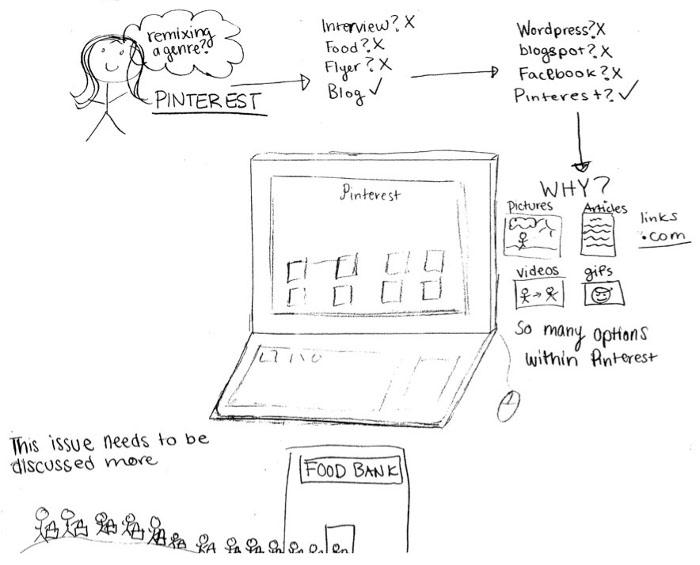

In general, assigning multiple reflective texts (across multiple genres and modalities) worked together as layers of reflective activity; one text often filled in missing information, added more detail, or expanded the scope of reflection. For example, Isabelle used her writer’s memo to reflect upon how her desire of the project being a form of social activism led her to pick Pinterest as a means of giving her audience information about her community partner and the social issue. The survey added reflection that it was in the initial brainstorming that Isabelle first thought to create a Pinterest board, a fact that she did not include in her writer’s memo. In the comic, she reflects upon how and why she first thought of Pinterest, through the questions and the check or x’s that follow them. Therefore, these pilot study results do not suggest that one genre of reflection is the “best” reflective genre, but rather that genre selection can indeed mediate what is reflected about, the depth of that reflection, and the scope of that reflection. Each reflective text had its affordances: the surveys allowed for targeted questions about material considerations that students might not consider as crucial factors of their composition processes and honest, critical reflection; the writer’s memos gave space for detailed, specific reflection on the final product; and the comics involved the interplay of visual and linguistic modalities, which led to the inclusion of a more holistic reflection from initial ideas to final products. These findings indicate the ways in which genres mediate reflection and its articulation.

Conclusion

This pilot study has pedagogical and research implications. The genre of the writer’s memo and the modalities employed within it as a written, linguistic-based form of communication tend to lend themselves to a narrative of success of a final project. Because students know this type of reflection articulation aids the instructor in assessment, students seem to see the purpose of this genre as justifying their design choices, and as such, the reflection is reminiscent of the academic argument genres students produce often in the college context. This type of reflection-in-presentation text becomes an argument about why their final product is exemplary rather than giving space for reflection on the many moments throughout the composition process. Future research on writer’s memos and similar reflective texts could employ corpus linguistics to see if this preliminary finding is consistent with a larger sample size. Corpus linguistic analysis could illuminate what types of clauses and morphemes are common in these genres and how those compare to the frequency of those found in first year writing argument papers.

Preliminary findings in this pilot study illuminate the ways comics and surveys might mediate reflection differently than the writer’s memo. The data suggests that the purpose of the genre and the modalities used within them might mediate reflection differently. As this pilot study demonstrates, uptake selection processes are incredibly complicated. DePalma and Alexander echo these findings; their case study about multimodal composition illuminates how students can struggle with the various rhetorical choices they have to make, particularly when they have to account for the interaction of multiple semiotic resources that they do not have experience controlling. Reflective texts can capture different parts of the composition process, and as we saw in this pilot study, each reflective text had different affordances. These affordances included the scope of what was reflected upon, the depth of the reflection articulated, and what reflection could be solicited. It is important, then, that composition instructors consider assigning varied reflective texts, in multiple genres and modalities, to more effectively mediate students’ reflections on these complex, multimodal processes.

Given the findings of this pilot study, future research on genre mediation of reflection should broaden the scope of texts gathered to include reflection-in-action texts. The time-sensitive and dynamic nature of uptake might call for the texts used here—the comic and/or writer’s memo, for instance—to be assigned before the project was due or might call for data-collection like participant directed video reflections, which would allow student authors to reflect as they were making choices. Alternatively, conversation analysis of collaborative reflection in group conversations, like Pamela Flash’s research on reflection on faculty conversations, might also be useful. Regardless of what genres are studied, I argue that researchers need to consider how genres incorporating non-linguistic modes allow for different types of mediated reflection. Another thing to consider when designing research studies of reflection is to think about what work genres tend to do and how that typified rhetorical response might have generic expectations that encourage some reflection selection processes over others, allowing for different types of metacognitive work. Also, it is imperative that we consider what questions we are asking when we ask students to reflect, regardless of which genre we ask them to use in doing that reflection. In this pilot study, the survey itself became a reflective text, asking students to retroactively map their uptake selection processes. The low-stakes nature of the assignment, along with what it asked students to reflect on, allowed students to reflect on factors they may have otherwise skimmed over.

When we ask students to reflect at the end of their project, some students use this opportunity as a means of making an argument for the effectiveness of their final uptake. The findings of this study encourage composition teachers to consider when reflective activities should be done. In this study, nearly all of the reflective activities were reflection-in-presentation texts. The free write and brainstorming sessions that students did in the beginning of their composition processes were both the first time students articulated reflection but also played a role in their eventual final project uptake. Neither of these activities were as strong of reflective activities as they could have been because the purpose of these in-class moments, as framed by me and taken up by students, was just to think of ideas—not to consider why they might have thought of them. When doing similar activities in the future, I would consider framing them as reflective moments, not designed just for articulation but also awareness and monitoring of what was articulated. The remaining reflective activities done in this assignment sequence—the writer’s memo, survey, and comic—were all due either alongside the final project or after they had submitted it. Though this was done to narrow the scope of this pilot study, the analysis of these texts suggest we consider the timing of when we assign reflective texts, including some reflection-in-action texts. Only assigning reflection-in-presentation texts allows students to “clean up” their reflections to highlight mostly (if not only) the successes, and in doing so, do metacognitive work mainly with things they think they did well. Because reflective genres used to aid in assessment tend to focus just on the finished project—their final uptake—rather than other moments in the composition process or even the composition process more holistically, students are not doing the metacognitive work of slowing down and dissecting their recursive revision strategies. Consequently, it is possible that students are missing an opportunity to engage in metacognitive work alongside different parts of their own complicated composition processes.

The importance of producing reflective texts goes beyond just doing metacognitive work about the choices within the final draft; it also can allow students to learn the intertextual nature of genres. As Russell and Fisher explain, “genres migrate in and out of the web, in and out of activity systems, resonating, inviting us to re-cognize them in relation to other systems, other possible motives and futures” (188). Given this intertextual relationship of genres, having students reflect on their own uptake selection processes while they are undergoing those choices can give them insight into what kinds of relationships exist between genres. Brian Ray explains, “studying [genres] through the concept of uptake allows us to trace paths between dissimilar genres and provide students with a clear sense of how ideas can circulate among them within larger ecologies or ceremonials” (191). This pilot study, then, does not just give us insight into how reflective texts are mediated through genres, but also works to help our pedagogy: it encourages us to consider how we might use multiple genres throughout the composition process such that students can map how their own work relates to other genres around them or the interconnectedness of genres more generally. In other words, reflection-in-presentation texts alone do not necessarily help students be metacognitive about the ways they mapped the rhetorical ecologies of their writing contexts, which may very well have been challenging to do and beneficial to reflect on in the hopes of transferring that skill to a future situation.

Perhaps most importantly, this study shows the complicated and nuanced decision-making that students undergo in composing a project. The factors at play in their uptake selection processes are both in and outside their control and they are constantly in-flux and changing importance levels. Therefore, reflection needs to be done throughout the composition process. If we want students to map their rhetorical choices throughout their composition processes, it might not be enough to wait until the end of the project to ask student “why” they created what they did; they might not remember all of the factors in their composition processes, which are not the same or constant throughout the process. Since Yancey’s groundbreaking work on reflection in the composition classroom, reflection has been used to cue, analyze, and assess transfer, specifically through asking students to write reflective texts (Brendt; DePalma; Read and Michaud; Rounsaville; Taczak; Yancey et al), but this pilot study makes it clear that we need to be more cognizant about what these texts can show us, always remembering how these reflective texts only show glimpses of the metacognitive work being done by our students. Given these preliminary results, future research should be done on how different reflective texts allow a variety of metacognitive practices. In the meantime, this pilot study gives us insight into how uptakes are occurring in dynamic ways throughout students’ composition process, and therefore we should provide a variety of reflection opportunities interspersed throughout students’ composition process, using a variety of genres and modes and asking a wide range of questions.

Appendices

Appendix 1

SA2: Genre Re-Mix

Background: This project is meant to prepare you for the 2nd Sequence. So far, we have practiced doing multimodal rhetorical analysis. In this assignment, we will transfer that analysis to design. You have two options for this assignment: 1) re-mix an artifact that you chose as evidence for MP1, or 2) re-mix your own MP1. What do I mean by “re-mix”? Once you pick your artifact, you will “re-mix” it by making your own multimodal creation. You may choose to have the same or a different purpose/audience as the original artifact. After you re-mix your original, you will write a brief (minimum 500 word) writer’s memo explaining your choices and experience with re-mixing your text. Remember, this is a short assignment, so that means that you should limit the scope of your project.

Format/Audience: Your choice!

Tasks for Remix:

-

Pick an artifact (from your community partner or your own MP1). (outcome 2)

-

Use modal affordances in your re-mixed multimodal creation to achieve your purpose to your audience. (outcome 1)

Tasks for Writer’s memo:

-

Pick an intended purpose, way of composing (must be different than original!), and audience—and tell me what those choices are – in the writer’s memo. Then, explain why you made the choices you did and what you did purposefully to achieve your purpose given your audience and design goals. Also, consider if you decided to create an easily recognizable genre, and if so, if you adhered to all genre conventions (or not) given your purpose/audience. (outcome 1)

Guided Questions:

What artifact do I want to choose? What is its purpose, genre, audience, and rhetorical strategies used?

How else can I imagine this projects purpose being represented?

How does this new representation modify the purpose, genre, audience, and rhetorical strategies used?

What is the piece of this project that I want of focus on? In other words, how can I create an artifact that is inspired by the original but potentially narrows the scope of what it is trying to do? What about the content do I leave out and what do I be sure to incorporate?

|

Short Assignment 2 Rubric |

Outstanding |

Strong |

Good |

Adequate |

Inadequate |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Pick an artifact (from your community partner or your own MP1). (outcome 2) |

|||||

|

Use modal affordances in your re-mixed multimodal project creation to achieve your purpose to your audience. (outcome 1) |

|||||

|

Pick an intended purpose, project design, and audience—and tell me what those choices are—in the writer’s memo. Then, explain why you made the choices you did and what you did purposefully to achieve your purpose given your audience/multimodal project. Also, consider if you decided to use a recognizable genre, and if so, if you adhered to all genre conventions (or not) given your purpose/audience. (outcome 1) |

Appendix 2

Survey Instructions: Please answer the following questions. This is a low stakes reflection activity due by tomorrow’s class.

- What did you originally think you were going to do for SA2? Why? If you still have a copy of the free write we did in class, write what you wrote here. If you no longer have the free write, then reiterate what you remember that you wrote here.

- What did you end up creating for SA2?

- What factors influenced what you decided to create for SA2? Time? Materials? Previous experience? Etc. And how did those factors influence your creation?

- Did you think of what you would create for SA2 during our class activity where we brainstormed how to remix a class text? Or how did you come up with this idea?

- Do you typically tend to enjoy creating something different than the “typical” writing assignment? Or do you typically prefer to write papers? Did you enjoy creating this assignment? Why or why not?

- What did you think I was looking for in this assignment? Were you trying to do what you thought I wanted? Or did you create something that you thought would be interesting, fun, or easy to create? Why?

- Any other things that you want to mention to me so I can understand how you decided to create the SA2:

Notes

- Within this article, each organization is unilaterally referred to as “community partner” for anonymity. (Return to text.)

- Arguably, all texts are multimodal. The New London Group, for instance, writes, “in a profound sense, all meaning-making is Multimodal” (p. 29). Though I agree with their sentiment, I am also emphasizing that the texts analyzed and produced in this course strategically used more than one mode to do meaning making work (e.g. brochures, websites, advertisements, promotional videos, etc.) (Return to text.)

- The survey was as homework assignment for all students in the class, but only the research participants had their responses used. (Return to text.)

- According to the writing program standards that this study took place in, students had both short assignments (2-3 double spaced pages or work equivalent) and major papers (5-7 double spaced or work equivalent). (Return to text.)

- All student names in this article are pseudonyms to protect the anonymity of the students. (Return to text.)

- CP stands for Community Partner, or the anonymous organization with which students did their service learning. (Return to text.)

- As a reminder, MP1 stands for Major Paper 1, or the 5-7 page paper that the students wrote before the remix project. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Alexander, Kara. From Story to Analysis: Reflection and Uptake in the Literacy Narrative Assignment. Composition Studies, vol. 43, no. 2, 2015, pp. 43-71.

Ball, Cheryl. Genre and Transfer in a Multimodal Composition Class. Multimodal Literacies and Emerging Genres, edited by Tracey Bowen and Carl Whithaus, U of Pittsburgh, 2013, pp. 15-36.

Bastian, Heather. Capturing Individual Uptake: Toward a Disruptive Research Methodology. Composition Forum, vol. 31, 2015, p. r.

Bawarshi, Anis. Accounting for Genre Performances: Why Uptake Matters. Genre Studies Around the Globe: Beyond the Three Traditions, edited by Natasha Artemeva and Aviva Freedman, Inkshed Publications, 2015, pp. 186-206.

Bawarshi, Anis and Mary Jo Reiff. Genre: an introduction to history, theory, research, and pedagogy. West Lafayette, Parlor Press, 2010.

Beach, King. Consequential Transitions: A Development View of Knowledge Propagation through Social Organizations. Between School and Work: New Perspectives on Transfer and Boundary-crossing, edited by Terttu Tuomi-Grohn and Yrjo Engstrom. Emerald Group Publishing, 2003, pp. 39-62.

Beaufort, Anne. Writing in the Real World: Making the Transition from School to Work. New York, Teachers College Press, 1999.

---. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Logan: Utah State UP, 2007.

Borton, Sonya and Brian Huot. Responding and Assessing. Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers, edited by Cynthia Selfe. Cresskill, NJ, Hampton, 2007, pp. 99-112.

Brent, Doug. Transfer, Transformation, and Rhetorical Knowledge. Journal of Business and Technical Communication, vol. 25, no. 4, 2011, pp. 396-420.

DePalma, Michael-John. Tracing Transfer across Media: Investigating Writers&Apos; Perceptions of Cross-Contextual and Rhetorical Reshaping in Processes of Remediation. College Composition and Communication, vol. 66, no. 4, 2015, pp. 615-642.

DePalma, Michael-John, and Alexander, Kara Poe. A Bag Full of Snakes: Negotiating the Challenges of Multimodal Composition. Computers and Composition: An International Journal, vol. 37, 2015, pp. 182-200.

Dryer, Dylan. Disambiguating Uptake: Toward a Tactical Research Agenda on Citizen’s Writing. Genre and the Performance of Publics, edited by Mary Jo Reiff and Anis Bawarshi. Logan: Utah State Press, 2016, pp. 60-80.

Dubisar, Abby, and Jason Palmeri. Palin/Pathos/Peter Griffin: Political Video Remix and Composition Pedagogy. Computers and Composition, vol. 27, no. 2, 2010, pp. 77-93.

Emmons, Kimberly. Uptake and the Biomedical Subject. Genre in a Changing World, edited by Charles Bazerman, Adair Bonini, and Débora Figuerido. West Lafayette, IN, Parlor Press, 2009, pp. 134-57.

Flash, Pamela. From Apprised to Revised: Faculty in the Disciplines Change What They Never Knew They Knew. A Rhetoric of Reflection, edited by Kathy Yancey. Logan, Utah State UP, 2016, pp. 237-249.

Freadman, Anne. Where is the subject? Rhetorical genre theory and the question of the writer. Journal of Academic Language & Learning, vol. 8, no. 3, 2014, pp. A1-A11.

Glaser, Barney, and Anslem Strauss. The Discovery of Grounded Theory—Strategies for Qualitative Research. London, Weidenfeld and Nicolson, 1967.

Gonzales, Laura. Multimodality, Translingualism, and Rhetorical Genre Studies. Composition Forum, vol. 31, 2015, p. r.

Johnson-Eilola, Johndan, and Stuart Selber. Plagiarism, originality, assemblage. Computers and Composition, vol. 24, no. 2, 2007, pp. 375-403.

Lutkewitte, Claire. Multimodal Composition : A Critical Sourcebook. Boston, Bedford/St Martin's, 2014.

McKee, Heidi, and Danielle DeVoss. Digital Writing: Assessment and Evaluation. Utah State UP/ Computers and Composition Digital, 2012.

Murray, Joddy. Nondiscursive Rhetoric: Image and Affect in Multimodal Composition. Ithaca, NY, State University of New York Press, 2009.

Ray, Brian. More than Just Remixing: Uptake and New Media Composition. Computers and Composition, vol. 30, 2013, pp. 183-196.

Read, Sarah, and Michael J. Michaud. Writing about Writing and the Multimajor Professional Writing Course. College Composition and Communication, vol. 66, no. 3, 2015, pp. 427-57.

Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition. Written Communication, vol. 28, no. 3, 2011, pp. 312-37.

Reiss, Donna, and Art Yong. Multimodal Composing, Appropriation, Remediation and Reflection: Writing, Literature, and Media. Multimodal Literacies and Emerging Genres, edited by Tracey Bowen and Carl Whithaus. Pittsburgh, University of Pittsburgh Press, 2013, pp. 164-182.

Rice, Jeff. The making of ka-knowledge: Digital Aurality. Computers and Composition, vol. 23, no. 3, 2006, pp. 266-279.

Roozen, Kevin. Reflective Interviewing: Methodological Moves for Tracing Tacit Knowledge and Challenging Chronotopic Representations. A Rhetoric of Reflection, edited by Kathy Yancey. Logan, Utah State UP, 2016, pp. 250-268.

Rounsaville, Angela. Selecting Genres for Transfer: The Role of Uptake in Students' Antecedent Genre Knowledge. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, p. r.

Russell, David and David Fisher. Online, multimedia case studies for professional education: Revisioning concepts of genre recognition. Genres in the Internet: Issues in the Theory of Genre, edited by Janet Giltrow and Dieter Stein. Amsterdam, John Benjamins Publishing Company, 2009, pp. 163-191.

Shipka, Jody. Digital mirrors: multimodal reflection in the composition classroom. Multimodal Composition: A Critical Sourcebook, edited by Claire Lutkewitte. Boston, Bedford/St Martin's, 2014, pp. 358-360.

---. Toward a Composition Made Whole. U of Pittsburgh, 2011.

---. Negotiating Rhetorical, Material, Methodological, and Technological Difference: Evaluating Multimodal Designs. College Composition and Communication, vol. 61, no. 1, 2009, pp. 343-366.