Composition Forum 39, Summer 2018

http://compositionforum.com/issue/39/

Passageways and Betweenity: A Brenda Jo Brueggemann Retrospective

With Contributions From:

- Brenda Jo Brueggemann

- Patricia Dunn

- Rachel Gramer

- Chad Iwertz

- Christopher Krentz

- Ryann Patrus

- Margaret Price

- Katherine Sherwood

- Eddie Singleton

- Shannon Walters

Introduction: Welcome to the Museum of Brenda

Brenda Jo Brueggemann has made an astonishing impact on the field of rhetoric and composition, and she continues to do so, by bringing insights from disability studies to our understanding of texts, rhetors, and classrooms. Brenda’s impact comes in a variety of modes: through her uniquely creative prose in a multitude of books and articles; her warm, generous presence, both physical and digital; and her multimedia work, whether it is composing a video about her relationship to Deafness and composition, curating art exhibits that explore disability and communication, or creating documentaries about community engagement projects. Thus this retrospective aims to articulate the impact of both Brenda’s work and her person in our field. As we discovered while drafting this essay, in many ways, it is impossible to separate Brenda’s scholarly contributions from who she is—how she converses, collaborates, and embraces her colleagues. In other words, Brenda herself embodies much of what she has researched and theorized, particularly in the ways she opens up the field of rhetoric and composition in an effort to be as inclusive and accessible as possible.

Notes on Content, Modes, and Access

Organizationally, this retrospective thematically traces Brenda’s work throughout her career, eschewing chronology in favor of highlighting key concepts from her career that recursively re-emerge both in her writing and her professional relationships. This thematic tracing, in the spirit of Brenda’s own commitment to collaboration and multiple modes of communication, is both multi-voiced and multi-genre. The words of the authors (Elizabeth Brewer and Lauren Obermark) are not the only ones you will read; and indeed you will quickly realize that words alone cannot encompass Brenda’s contributions to the field. One voice we frequently integrate is that of Brenda herself, as we begin each section with an excerpt from one of her publications. These excerpts felt increasingly necessary as we composed this retrospective. Brenda’s style is so unique—it is complex yet clear, weighty yet whimsical. We want to offer a traditional introduction to some of her core conceptual contributions and maintain the cadence and tone of her always memorable, always thought-provoking prose. It is this rich prose that makes her work influential among disability studies scholars across many fields while also allowing her essays and books to be incredibly teachable in a variety of classrooms, from first-year writing to specialized graduate seminars.{1}

In addition to these excerpts from Brenda’s work that begin each section, we end each section with another set of voices: those of Brenda’s colleagues. When we began imagining this retrospective, we consulted with Brenda, who suggested that a retrospective about her work would ideally be a collective endeavor, and one that would be composed of much more than alphabetic text. In short, from the inception of this project, we wanted the retrospective to be inclusive of an array of voices and perspectives and designed with multiple modalities and access in mind. That means that the videos in this text are captioned and some have additional transcripts. All images include alternative text (or, alt-text) that can be read by a screen reader, and most of the images additionally include descriptions and transcripts in the essay itself. Furthermore, we have attempted to write using plain language that readers either new to or very familiar with rhetoric and disability studies will understand. In these ways, the retrospective, we hope, enacts many of the core commitments of Brenda’s career.

When we reached out to people to contribute to this piece, we suggested that they could send us “artifacts,” broadly defined, about their interactions with Brenda and/or her scholarship. In framing these contributions as artifacts, we propose that the retrospective overall be understood as a digital museum—a Museum of Brenda, if you will. Elizabeth and Lauren are the designers, curators, and guides at this museum. But the museum could not exist or communicate its ideas without the artifacts—texts, videos, photos, and art—and the artifacts in the Museum of Brenda come from many different people who have been influenced by Brenda in a variety of important ways.

Notes on Options for Navigation

Since our favorite museums allow for flexibility and choice among visitors, we have worked to create a similar atmosphere in this essay. While you may certainly navigate the article linearly, reading from beginning to end, we also encourage you to play around a bit. We have added hyperlinks throughout the article that will take you to other sections, so if a particular idea intrigues you, you can follow that link at that very moment. The themes of Brenda’s work are networked and entangled, not nearly as separate as our organizational scheme might imply. The links allow for a more organic, spontaneous jumping around through these themes, a productively messy exploration of the network.

Additionally, you will see a sticky menu designed to follow as you scroll through the text. At any point, you can use that menu to access certain themes and artifacts. We hope this menu gives you a helpful sense of the museum overall—the themes, the artifacts, and the contributors—and allows you to pick and choose certain areas that strike you as the most relevant to your needs and interests at the time of your visit. Then, perhaps, during another visit to the Museum of Brenda, you can use the menu to “pop in” to other areas. The beauty of a museum, and the same can be said of Brenda’s work, is that you can visit multiple times and always stumble across something new or understand something “old” in a fresh, surprising way.

Introductory Artifact: Meet Brenda Jo Brueggemann

The first artifact we include is one composed by Brenda herself. It is a video entitled Why I Mind; she frequently uses this video to introduce herself when leading workshops. This video briefly explains how Brenda came to understand her own identity as a Deaf woman and, even more, how she came to study the intersections across disability, especially deafness, rhetoric, and composition. Like so much of what Brenda has composed, this video is quite teachable, whether offering advanced students a glimpse into disability studies or serving as a model literacy narrative for first-year writing students.

Brueggemann's Why I Mind Video

Disability as Insight

“On the first day of my honors first-year composition course, after I had ... given a brief speech about why ‘Abilities in America’ was my chosen theme for this particular course ... ‘Your turn,’ I said. ‘Go ahead, pick one item on this list, grab a few classmates, and spend the next five minutes seeing if you can figure out a relation to disability.’ ... ‘Body piercing,’ offered one young man, the chosen spokesperson for a group of non-pierced bodies in the corner by the door. He shrugged. I jotted a quick note to myself: ‘What bodies can/can't do to themselves; crippling one's self; cf. Goffman's Stigma’ (Although I didn't tell them about it, I thought of sadomasochist Bob Flanagan, a performance artist with cystic fibrosis, and his profoundly transgressive film, Sick.) Body piercing and disability—I hadn't thought of that.”—Brenda Brueggemann, An Enabling Pedagogy 807-808.

Disability is related to every topic, which Brenda demonstrated for her class in the activity recounted above, and which she has argued persuasively in both An Enabling Pedagogy and Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities. Her point is much more consequential than the first-day game with her students suggests though; in fact, her larger argument is that “disability enables insight—critical, experiential, cognitive, sensory, and pedagogical insight. And it is this enabling, this insight, that I am after in all my classrooms, whether disability is the ‘subject’ or not” (An Enabling Pedagogy 795). Brenda’s play on the terms disable and enable upend readers’ expectations about what disability and ability mean because she demonstrates that disability makes the work of the humanities possible. That disability is a lens for understanding our world and position from which knowledge is created means that it is indispensable for the humanities.

The revolutionary idea that disability is critical insight, rather than lack or deficit, has laid the groundwork for all future applications to rhetoric and composition, among other disciplines. For example, Brenda’s central point that disability is a necessary and fruitful perspective has been followed by scholars including Jay Dolmage, Stephanie Kerschbaum, Margaret Price, and Melanie Yergeau. These writers have urged our field to re-figure the history of rhetoric to include disabled composers and to redesign our classrooms to be accessible, hospitable places for disabled students and faculty. Conversations about designing accessible webtexts by envisioning disabled people as both users and producers (see Yergeau et al.’s Multimodality in Motion), along with writing welcoming syllabus statements on accessibility (see Wood and Madden’s Suggested Practices for Syllabus Accessibility Statements) are just two examples of work that follows from Brenda’s point that disability is insight.

Furthermore, Brenda and her coauthors’ work in Disability Studies: Enabling the Humanities shows that disability is central to human experience (Snyder et al 1). Approximately 20% of the population in the United States has a disability of some sort, yet so often the “norm” is considered nondisabled. While disabled people are a huge subset of the population and of our culture (just think about the many examples of disabled characters and authors in canonical literature), Brenda argues that too often they are missing from our critical consciousness (3). A related take-away from the introduction of this collection is that disabled students and faculty are present in large numbers in our universities. And once disabled students get to college, they face an environment that ignores them or is even hostile because it was designed for normative, nondisabled bodies and minds. One of the first realities they encounter is that they no longer have the legal protections afforded to public school K-12 students (3). Brenda’s work not only illuminates the presence of disability, it suggests more equitable pedagogical practices for teaching writing to students with a range of different bodies and minds. Brenda’s mission of creating more accessible universities has been taken up by other scholars such as Jay Dolmage who, in his influential essay “Mapping Composition: Inviting Disability in the Front Door,” argues that despite our best intentions, “composition is not always an accessible space” because it relies on the deficit model (14).

One of the books that Brenda is best known for in rhetoric and composition is her co-edited sourcebook, Disability and the Teaching of Writing, published in 2008 (Brueggemann, Lewiecki-Wilson, and Dolmage). This book demonstrates concretely what insight a disability perspective brings to common practices in composition. In their introduction to this collection, Brenda and Cynthia Lewiecki-Wilson explain the productively complex atmosphere that comes when disability is a course theme in a writing class. They share from their own experiences that “the critical concepts of disability studies help us and our students examine language and images ... thereby improving literacy skills and leading writers to give greater consideration to their rhetorical choices and the effects their choices may have on people and practices” (4). But disability studies also encourages us, as teachers, to question our own reliance on “the norm” to place students based on their status as English language learners, learning disabled, or in need of basic writing. When we consider the power that assumptions have about what a “normal” student can do, we are forced to reconsider the ways our teaching practices may inadvertently be exclusionary. Brenda and Lewiecki-Wilson note that “the inclusion of students with disabilities and the topic of disability offer an opportunity to change teaching methods and content so that they provide more flexibility and choice for various kinds of students” (6). Disability and the Teaching of Writing, though now ten years old, still functions as an accessible way of introducing central concepts of disability studies to English Studies (and the humanities) more broadly, from freshmen to faculty.

Artifact on Disability as Insight

Shannon Walters’ narrative artifact, featured below, not only includes gratitude for Brenda’s support, but also demonstrates the profound impact that Brenda’s scholarship has had on our field. Walters notes many of Brenda’s most central concepts and publications, connecting these to her own life and work, and in the process demonstrating how disability studies has proven influential and insightful throughout her career so far.

I first met Brenda Brueggemann during my own “passageway” and “betweenity” when I was applying to PhD programs. I knew enough about my own project at that point to know that I’d be very lucky to work with her. Lend Me Your Ear was one of the first things I read that made me know what kind of project I wanted to tackle in rhetoric and disability studies. As it turned out, I didn’t end up going to the graduate program Brenda was a part of then. I agonized over this decision, but what made it easier was knowing that Brenda was interested in my work either way. She sent encouraging replies to my emails, and made me feel like no decision was the wrong one. In that I felt truly supported.

It strikes me now that Brenda has been with me at several passageways and betweenities in my life. I read about what she calls her own “‘academic woman’ balance narrative” as I started my first job (See Balliff et al., Women’s Ways of Making It in Rhetoric and Composition). Then, I read about her updates and reflections on that narrative in No Day at the Beach (See Brueggemann & Gramer) as I negotiated juggling family and work and moved onto a new stage in my career. I was also honored to have Brenda visit Temple University for a writing and disability symposium in 2012. At all of these critical junctures, it’s fair to say Brenda’s “enabling pedagogy” has critically influenced me and shaped me in ways that I continue to appreciate and discover. —Shannon Walters

The Will to Speech Meets the Will to Listen

“Throughout this book, then, I speculate on deafness as rhetoric, on what Lennard Davis has called ‘deafness and insight,’ and the way we might reconceive rhetoric by listening to deafness. I aim for conceiving a will to listen that is born, ironically enough, from listening to deafness. Here I speak (or rather, write—they are not, after all, the same) of concepts quite familiar to Western rhetoric—of ‘speaking subjects,’ ‘the good man [sic] speaking well,’ and the Aristotelian tradition of audience analysis. I question a tradition that places all the burden for understanding on listeners, but all the authority on speakers. In rhetoric, we have, for instance, no tradition for ‘listening,’ no ‘art of listening well’ to accompany 2,500 years of theory and practice in ‘speaking well.’ And, finally, coming from the constructions of deafness I have examined, I suggest space for a rhetoric of silence, [as] well as time for a rhetoric of responsive and responsible listening that matches our rhetorical responsibilities for speaking—time for a rhetoric that lends its ear” —Brenda Brueggemann, Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness, 17

As we have demonstrated in our discussion of disability as insight, over the course of nearly two decades, Brenda has made great strides in bringing important discussions about disability to bear on rhetoric and composition. Her first book, Lend Me Your Ear: Rhetorical Constructions of Deafness (1999) offers another central example of this bridge building. A central question circulates in this book: how does the rhetorical tradition overlook those who do not (orally) speak? Brenda questions rhetoric’s emphasis on the “will to speech,” pointing to Quintilian’s “good man speaking well” as one ancient and oft-cited example of this emphasis. She deftly interrogates the ways in which this emphasis on speech excludes many rhetorical subjects, especially D/deaf rhetors. What Brenda calls the “will to speech” is at the heart of the rhetorical tradition, and she voices concern that this puts great burden on listeners and all the authority with the speaker; there is no “art of listening well,” no “will to listen,” and Brenda advocates for a space for such theories as an ethical responsibility in the ongoing rhetorical tradition.

This interest in listening has now been thoroughly engaged in the discipline, particularly by feminist scholars like Cheryl Glenn (Unspoken: A Rhetoric of Silence) and Krista Ratcliffe (Rhetorical Listening: Identification, Gender, Whiteness). In short, early on, Brenda urged those of us in rhetoric and composition to pay as much attention to listening as we do to speaking, both in how we theorize and how we teach. And in this attention to rhetoric as a will to listen, Brenda makes the field more inclusive and equitable.

Artifacts on Listening and Inclusivity

The two artifacts we share to conclude this section illustrate how Brenda opens up the field with her own ability to listen and, accordingly, make colleagues feel welcomed into a community. Below is a video from Margaret Price. Price shares about what she calls “the quintessential Brenda gesture” of opening her arms and smiling widely, welcoming Price to a disability studies workshop the first time she attended the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC).

Video text transcript:

[First, Margaret speaks.]

I didn’t actually meet Brenda until later on, at my very first CCCC conference, which I attended in Minneapolis. And I was with my wife at the time, and I decided to attend at the last minute a half-day Wednesday workshop on the topic of disability studies. This would have been about in the year 2000. And my wife was urging me strongly to go to this workshop and I was you know sort of waffling and I was like I don’t know I’m too scared. And finally you know she sort of nudged me in there and I remember so vividly standing at the doorway of this ballroom where the workshop was held. It was an enormous ballroom, it was dimly lit, and the people at the workshop were clustered at some tables way over near the stage. And I think I almost turned around and left again. But I kind of pulled up my courage and went creeping into the room and I was crossing this enormous floor which was probably covered by a really garish carpet. And I was just crossing what felt like this enormous distance over to the scholars at the far side of the room. And Brenda was sitting at one of the tables in such a way that she had a view of the door I was coming in. She saw me. She had never met me in person before. And she looked at me and she smiled a huge smile and she opened her arms like this.

[Margaret opens her arms wide and smiles broadly.]

And I will never forget that gesture. She had no idea who this person was, or why this person might look so creeping or so timid and she just made this gesture that I think of as quintessentially Brenda.

[Margaret opens her arms again.]

And to me the gesture is so important because it says not only, I see that you’re here, I recognize that you’re here. It also says, I’m glad you’re here. So ...

[Margaret signs “thank you” in ASL.]

Both Price’s artifact and the next one from Patricia Dunn recall the early years of disability studies in rhetoric and composition and Brenda’s role in creating a community. Dunn writes specifically about her experience connecting with Brenda at CCCC in the late 1990s. This community that Brenda helped establish paved the ways for collaboration across many years, allowing disability studies to weave its way more firmly into composition, at the CCCC convention and in the pages of major journals. Brenda listened, collaborated, and, along with her co-panelists and co-authors, has been influentially heard throughout the discipline and beyond.

In the late '90s, I was having trouble getting my individual proposals on learning disabilities accepted to CCCC—though my other proposals hit. On the last day of the '98 conference, I mustered my courage and approached anybody I could find on the program that year doing anything related to disability—there weren’t many—and asked if they wanted to collaborate on a proposal for the next year. They all said yes. A year later, Brenda Jo Brueggemann, Linda Feldmeier White, Barbara A. Heifferon, Johnson Cheu, and I presented a session at CCCC in Atlanta called, “Challenging Constructions of Disability: How Writers with 'Disabilities' Contribute to Composition Praxis.” When it was over, Brenda said something like, “We should send our panel papers to CCCs [College Composition and Communication]” I thought, “Is that done? Do people do that?” Brenda had no doubt and went about organizing how we would tweak our papers in order to make them into a cohesive journal article. The result: Becoming Visible: Lessons in Disability, published in CCC in February, 2001—over 17 years ago. Eleven years after that first CCCC presentation, Brenda and I collaborated again, this time with Margaret Price, on a panel called, Disability Studies Meets Composition: New Questions for Theory, Practice, and Research. It was a Featured Session at the 2010 CCC. Brenda’s passion, enthusiasm, and humor continue to encourage collaborations among scholars in multiple disciplines.” —Patricia A. Dunn

Betweenity

“For some time now, I have been imagining a theory of ‘betweenity,’especially as it exists in Deaf culture, identity, and language ... whether deaf, disabled, or between—I’m finding I’m generally more interested in the hot dog than the bun, the cream filling than the Oreo (which, if you’ve noticed, has been changing a lot lately) than just the twinned chocolate sandwich cookies on the outside. Give me a hyphen any day. To be sure, the words on either side of the hyphen are interesting, too, but what is happening in that hyphen—that moment of magic artistry there in the half-dash—is what really catches my eye.” —Brenda Brueggemann, Deaf Subjects: Between Identities and Places, 9

Brenda consistently explores a theory of “betweenity,” what she sometimes calls “working the hyphens.” {2} In her book Deaf Subjects: Between Identities and Places, betweenity takes center stage. She offers varied case studies of deaf subjects and practices that fall in this space of betweenity. For instance, one chapter, crafted in an accessible and creative epistolary form, Brueggemann imagines herself writing letters to Mabel Hubbard Bell, Alexander Graham Bell’s deaf wife. Brenda writes of a kinship with Mabel, as both of them are women who engage with their deafness in different ways depending on their context and audience. In short, both Bell and Brenda complexly embody deafness as rhetoric and identity, thwarting clearly defined labels and moving between worlds; there is no clear division between personal-professional or hearing-deaf. They are instead women who “work the hyphens” of these binaries, and, as Brenda articulates it, it is in these hyphens where the magic happens, where the good stuff lives, the cream in the Oreo.

With betweenity, as Brenda both lives it and theorizes it, identity is far from stable, always fluid and shifting and, at the same time, central to one’s practices of language. Thus Brenda offers scholars and teachers of composition a new way to understand how their own identities inflect and affect their places in the field, as well as a thoughtful lens through which to better understand the identities of their students, disabled and otherwise.

Artifacts on Betweenity, Academic Work, and Vulnerability

Many artifacts contributed to this retrospective address betweenity, which speaks to its theoretical and pedagogical richness; you will note its emergence in artifacts in other sections as well. First, we share a video from Margaret Price, in which she speaks about how betweenity shapes all academic work because it is theory that values liminality and acknowledges humanity.

Text transcript of Price video:

[First, Margaret speaks.]

My first memories of Brenda are actually through her book, Lend Me Your Ear. I read it when I was just starting out my PhD program, and also taking an ASL class. And at that time, at my school, I was the only person in the English Department working in disability studies, graduate students or faculty. And I was also the only person learning ASL in the department. So I turned to books a lot for companionship, and Lend Me Your Ear spoke to me on so many levels. It talked about so many things that I had wanted to learn more about that that really had been my motivation for even going into rhetoric and composition. I wanted to learn more about language, and its connection to advocacy and disability.

More about deafness, more about language, more about connections between deafness and queerness. And Lend Me Your Ear had all of it. And also had tons of stuff that I had never studied before, had never done before, but I immediately wanted to do, like doing empirical research. When I read the book, I was compelled by every chapter and I remember how clearly and how beautifully the interludes, the pieces of creative nonfiction spoke to me through that book. I still teach the essay On (Almost) Passing just about every year to my undergraduates and they’re always amazed by it. And particularly this notion that Brenda has become very famous for, which is the notion of betweenity. And I feel as though I carried that idea forward into all virtually of my academic work—the notion of betweenity and liminality as an exciting, productive, creative space, but also a space where we are very vulnerable and very human and can be open to all kinds of things.

Next, we include a video from Ryann Patrus, who discusses the ways that Brenda’s theory of betweenity allowed her to better understand the complex lived experiences of Deaf and hard-of-hearing women in her own research.

Text transcript of Patrus video:

[Now Ryann speaks.]

Brenda's work on Betweenity has had a huge impact on my research with deaf and HOH women and was critical to articulating the nuances of these complex experiences. Her work helped me think through the many “in-betweens” that exist within communities and identities and provided a framework for thinking through how these “in-betweens" show up in the lived experiences of disabled and Deaf women.

Finally, we share a textual artifact from Rachel Gramer. Similar to Price, Gramer highlights the ways that vulnerability can be part of betweenity, particularly when a person is developing their identity as a as a scholar and teacher, as Gramer was when she first met Brenda. Gramer was in-between places and experiences, newness in the present (and future) bumping awkwardly, or even scarily, against one’s past. Brenda acknowledged this vulnerable betweenity with both safety and humor.

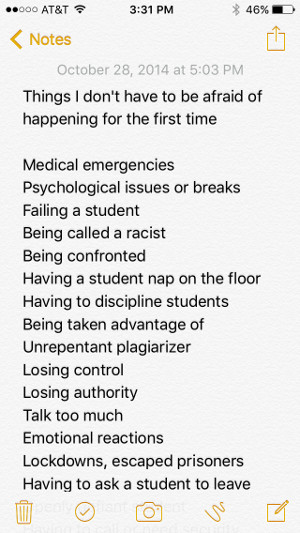

Open up: Scary Things

My first (and only) graduate course with Brenda was ENGL 602: Teaching College Composition (a.k.a. the practicum). It was my third version of the practicum in rhetoric and composition, and I entered with five years of high school teaching experience and one year of teaching at the two-year college level. During the week of Halloween, Brenda began class by asking us to make a list of “Scary Things” that we were concerned about as writing teachers in that moment. Then, she asked us to go around the room and individually share with the large group whatever we felt comfortable sharing. More than half of the graduate students in the course were first-time teachers who had a slew of concerns ranging from medical emergencies to student defiance.

As the new teachers in the room spoke, I realized that many of their fears had not made my own list of “Scary Things,” because I had already experienced so many of them. So I began to make a list of “Things I don’t have to be afraid of happening for the first time,” which I still have saved in the Notes in my phone to this day. (The list is a combination of others’ concerns and my own memories of my early teaching. For instance, having a student nap on the floor and school-wide lockdowns for escaped prisoners were two specific high school teaching experiences of mine.) I didn’t make the list because I wanted evidence of my experience or expertise, or others’ inexperience or fears. I made it because I realized I had already forgotten or internalized so many earlier teaching fears and concerns. Until the conversation that Brenda opened up (each year) with newcomers teaching for the first time.

Things I don’t have to be afraid of happening for the first time

- Medical emergencies

- Psychological issues or breaks

- Failing a student

- Being called a racist

- Being confronted

- Having a student nap on the floor

- Having to discipline students

- Being taken advantage of

- Unrepentant plagiarizer

- Losing control

- Losing authority

- Talk too much

- Emotional reactions

- Lockdowns, escaped prisoners

- Having to ask a student to leave

Each of the items on this list had its own story shared that day in a safe space for new teachers to open up and reveal not just what they feared, but what was underneath those fears: what they thought they should be prepared for and how they thought they should act and be in relation to their students. That safe space would not have worked with just any teacher-faculty member (I speak from experience there, too, as I’m sure we all do). Brenda had to do the work all semester to open up safe space for new teachers to feel comfortable speaking when any number of things do not feel safe (e.g., new job, new institution, new educational expectations of graduate school). Each of the stories shared there contributed to a felt sense of fear and uncertainty; yet in their collectiveness, our stories together created a safe opportunity to speak fears without judgment, acknowledged with Brenda’s “Yeaaaahhhh” and its humming reassurance.

On a scholarly level, the conversation Brenda opened and led helped me begin to consider how much my previous teaching experiences had shaped the kinds of stories I was telling about my teaching abilities and identities, which intersected with any number of other events and memories that pushed me down the path to my dissertation: a year-long narrative interview study eliciting stories of teaching and learning from five new graduate student teachers. On another level—deeper and broader—the structuring of “Scary Things” showed me how to be a kind of teacher and teacher-mentor I didn’t even know I wanted to be: one who cracks open fears by drawing them out and hearing them spoken in the voices of others, one who is the kind of person/teacher/scholar who is able to open up safe space for truths that don’t feel safe. Some may say this is part of the “science” or “art” of teaching, and there are certainly techniques for creating safe space; but in my experience, this is also very much part of the “magic” of teaching well when someone takes a deeply open stance toward collective vulnerability and voicing of that vulnerability. And does so on Halloween, and names it “Scary Things,” so that we can all laugh from the start. —Rachel Gramer

Multimodality and Interdisciplinarity

“Technology itself mediates, transforms, blends and enables a ‘bicultural’ life for modern deaf/hard-of-hearing people ... Writing itself has always been a technology—for both better and worse—in service or in strain with deaf people’s lives and their articulation of their self, selves, and community,” —Brenda Brueggemann, Articulating Betweenity: Literacy, Language, Identity and Technology in the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing Collection

Brenda’s scholarship tells meaningful stories exceptionally well, and often these stories illuminate a broader range of Deaf lives and rhetorical practices. Brenda has shown in particular how technologies of communication both facilitate and constrain everyday activities for Deaf individuals. As Dan Anderson et al. noted in 2006, the field of rhetoric and composition has realized that “the bandwidth of literacy practices and values on which our profession has focused during the last century may be overly narrow” (59). Brenda’s illumination of the ways in which Deaf people make meaning beyond spoken and written language is a valuable and unique contribution to the field’s understanding of multimodality and the importance of technology. In her own mediated webtext, Articulating Betweenity: Literacy, Language, Identity and Technology in the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing Collection, Brenda analyzes literacy narratives from Deaf and hard-of-hearing people, and she weaves these stories in with her own. One of her own video narratives within this webtext remarks on her time at Gallaudet University and the extraordinary pressure students in a basic writing class felt to communicate in Standard English; for many of these students, English must have been their second language after American Sign Language. In her reflection on this time at Gallaudet, Brenda notes that technologies, including writing, “can surely aid one’s literacy learning and interactions, [but] they can just as easily strip it away.” These Deaf students in basic writing learned the privilege the academy accords to essayistic literacy and Standard English, but they recognized they were on the margins of that power and that it grated against their identity and other forms of communication.

All of the narratives within this webtext demonstrate the complex relationships that Deaf people have with technology. Other videos Brenda analyzes include that by Warren Francis, a Deaf undergraduate student in Computer Science who wants to create technology to simulate what different deaf people hear and to better adapt audiologist’s tools to individual deaf people’s needs. Brenda’s analysis of this video emphasizes the important role that Deaf people should play in designing technology for their own needs, rather than in simply being the recipients of services. But in Brenda’s third analysis of an anonymous literacy narrative, the Deaf student author explains how technologies such as captions and the Internet have changed her life as a user/consumer in many positive ways, including increasing her occasions to communicate through written English. Importantly, Brenda’s choice to compose both a multimodal and an accessible text signals that she is not just recovering narratives about technology, but she has designed her own webtext with a broad audience in mind, rather than a presumed nondisabled reader.

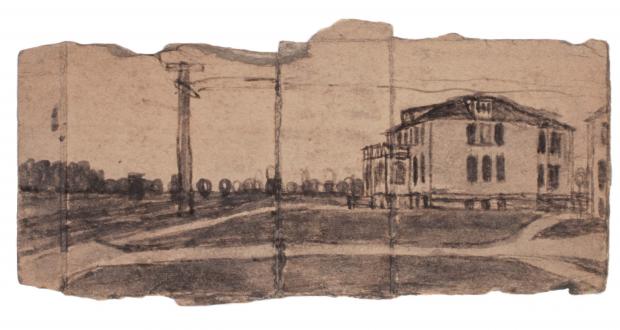

Brenda has worked across disciplinary boundaries to recover d/Deaf lives and communication practices that extend beyond text and into art. Her interest in technologies of communication reaches outside what we in rhetoric and composition might immediately think of, such as the Internet, and includes visual forms of communication. Probably the best example is her recovery project of deaf, self-taught artist, James Castle, which resulted in an art exhibition of his work. Even though Castle did not speak or use sign language, his artwork demonstrates play with language and a yearning for human connection. Brenda’s study of Castle’s work has helped him become a well-known folk artist, and it serves as a significant contribution to our field’s conception of multimodality and rhetoric.

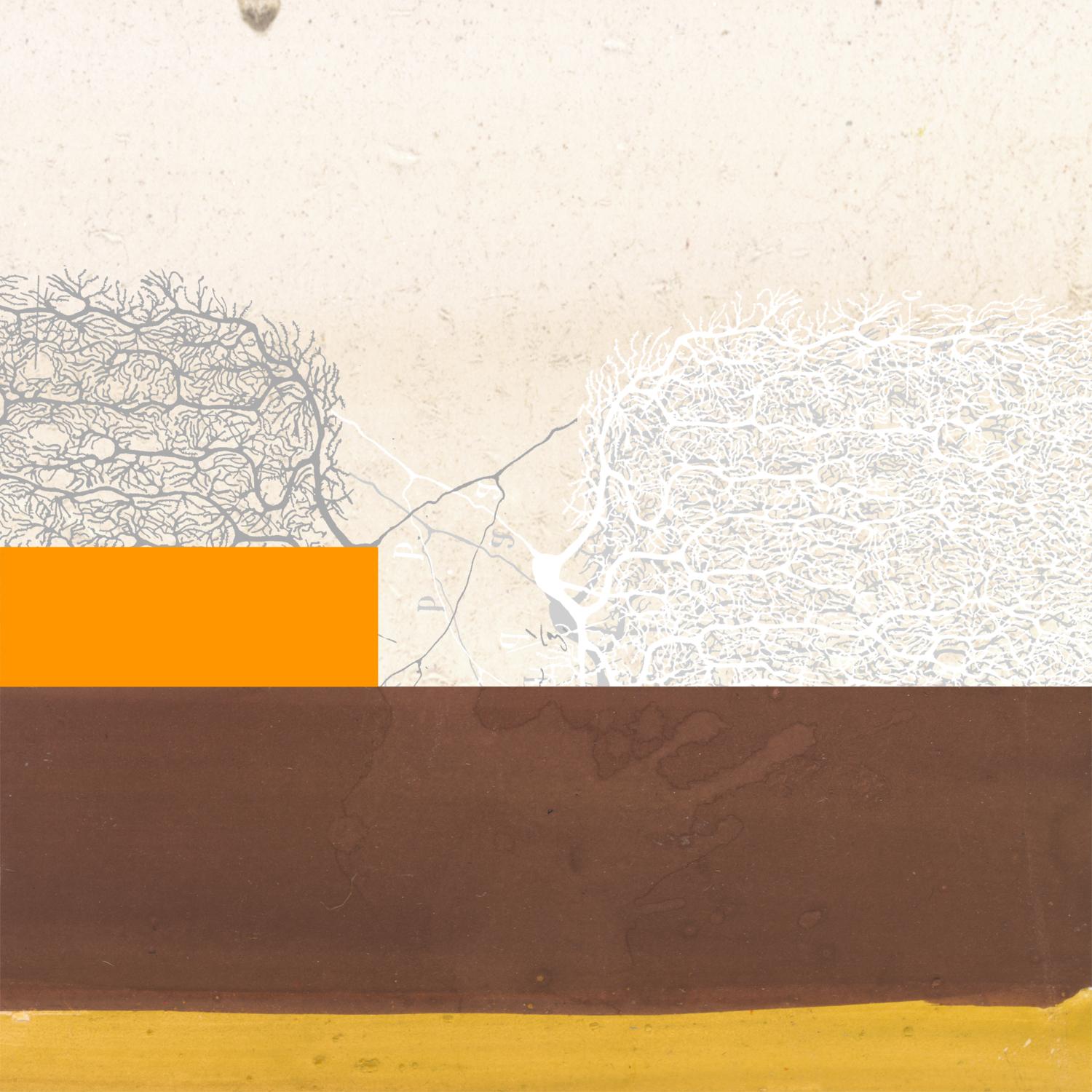

Artifacts on Multimodality and Rhetoric, With a Focus on deaf Artist James Castle

In the artifact below, Katherine Sherwood has paired a Castle illustration with one of her own works of art, titled Collaboration, as a way to visually represent the professional partnership that she has had with Brenda. The first picture is the Castle illustration, featuring the deaf school that he briefly attended. The second picture is the one created by Sherwood, featuring intertwining roots over bright brown and yellow blocks of color. Sherwood also includes a note with her artifact, thanking Brenda for their collaboration.

ABOVE: James Castle, Untitled, n.d., found paper, soot.

ABOVE: Katherine Sherwood, Collaboration, 2006, digital print.

THANK YOU BRENDA MY DEAREST COLLABORATOR IN ALL THINGS JAMES CASTLE. —Katherine Sherwood

We also include below a photo artifact, from the authors. This photo features Elizabeth, Lauren (with her one-year old son in a baby carrier), and Brenda at the opening of the James Castle exhibit in Columbus, Ohio, in 2012. They all smile widely, including the baby, enjoying the community-oriented event and Castle’s work, celebrating Brenda’s work as the curator. The photo speaks to the way that art as multimodal rhetoric, and indeed rhetoric that centers “disability as insight,” solidified the relationship between the three women.

Embodiment in the Classroom: On Passing and Coming Out

“My premier pedagogy for passing is, of course, writing. My students, even in the more literature-based classes, write a lot. They always keep journals; they always write too many papers (or so it seems when I’m reading and responding to all of them). And my students, for fourteen years now, are always amazed at how much I write in responding to their journals and papers (they tell me so in evaluations). For here is a place where I can have a conversation, unthreatened and unstressed by my listening limitations. They write and I write back. Writing is my passageway; writing is my pass; through writing, I pass.” —Brenda Jo Brueggemann, On (Almost) Passing, 659-60

“In our own cases, we have been able to perform normalized identities; we can pass in the usual sense of the word. It is, in part, this flexibility in performing our identities that we seek to theorize. For many years Brenda passed as able-bodied in the classroom, never publicly or pedagogically disclosing her hearing loss; similarly, for many years Debra passed for heterosexual (meaning that she identified her sexual orientation in this way), and then for several years she passed as heterosexual (meaning that she hid her lesbian orientation from her students). At about the same time in our teaching careers, however, we made the ethical choice that Caughie (1999: 247) refers to by seeing subjectivity as a ‘practice and a responsibility.’ We began performing our identities as disabled (Brenda) and lesbian (Debra) but also called attention to those performances as performances, compelling our students to engage not simply with our performed identities but with identity formation itself.” —Brenda Jo Brueggemann and Debra A. Moddelmog, Coming-Out Pedagogy: Risking Identity in Language and Literature Classrooms, 313-14

While many scholars discuss passing and coming out in relation to their identities, Brenda’s work specifically addresses how these concepts manifest for disabled people. Even more, she often writes about passing and coming out in a pedagogical context. In her essay On (Almost) Passing, she artfully describes moments in her own life where she passes in various ways: on dates with a high school boyfriend; at the movie theatre with her husband; at the grocery store in an awkward exchange with the cashier; and in her classroom, among her students. As she describes passing in the classroom, she shares her reliance on the use of writing, group activities, and student leadership during class time; specifically, she notes her voluminous feedback on papers, her use of breakout groups, and students co-leading class discussion. While readers likely view Brenda’s description of her pedagogy as part and parcel of being a committed and experienced teacher of writing, she also notes that her pedagogy is connected to “getting me past some of the more difficult aspects of teaching” (659). Writing is then positioned as a way to converse with students, to listen even when hearing is a struggle. As we note in the epigraph to this section, Brueggemann concludes her essay as follows: “For here is a place where I can have a conversation, unthreatened and unstressed by my listening limitations. They write and I write back. Writing is my passageway; writing is my pass; through writing, I pass” (659-60).

While Brenda connects acts of passing to writing, she also connects acts of coming out to performance in the classroom. In a piece co-authored with Debra A. Moddelmog, they discuss the risks and rewards—and oh-so-much more in-between—of disclosing disabled (Brenda) and lesbian (Moddelmog) identities in the classroom. In disclosing such identities, they note, knowledge is created and negotiated alongside students. More specifically, part of the act of coming out also entails an explicit discussion with students about what these identities mean, how they have been marginalized, why they traditionally might not be made public to students. In this way, a teacher’s embodied identity becomes part of the content of the course. At the same time, Brenda and Moddelmog also acknowledge that even claiming a “historically abject” (310) identity is complicated in practice because, for them, these identities are “largely invisible and provisional,” resulting in simultaneous and entangled passing and coming out (312).

Brenda often allows complex questions of identity to lay beside classroom practices, flowing through one another, informing each other, sometimes interweaving in honest, uncomfortable, yet entirely necessary ways. Her work illuminates identities as never separate from the work compositionists undertake with their students, as much as we might want them to be at times, and this is especially important to keep in mind in the case of disability and the teaching of writing. Through Brenda’s discussions of passing and coming out, the field can develop a stronger sense of how to allow disability to inform composition in difficult but profound ways.

Artifacts on Embodiment

The first artifact we include in this section is a text from Christopher Krentz, who discusses Brenda’s service and mentorship. Krentz notes that it was mentorship that was particularly important because of Brenda’s embodied identity as a tenured deaf professor—a rarity at hearing universities.

Brenda Brueggemann has been one of the shining stars in the emergence of disability studies as a recognized field. With incredible energy, enthusiasm, intelligence, and dedication, she has produced remarkable scholarship, taught countless students, generously mentored younger scholars, and done a dazzling amount of meaningful service, from working on the MLA’s Committee on Disability Issues in the Profession to serving as president of the Society of Disability Studies. She brings her characteristic wit to everything she does. As one of the few tenured deaf/hard of hearing scholars at a “hearing” university in the nation, she has served as an important model and mentor for me personally. We are lucky to have Brenda in our midst! —Christopher Krentz

The second artifact we share in this section is a video from Chad Iwertz. In this video, Chad discusses the influence that betweenity has on how he studies transcription. Through Brenda’s articulation of betweenity, he came to see access itself as embodied, especially in relation to captions, which, in his words are “living, embodied forms of access that write themselves among the bodies that design, read, and study them.” Iwertz demonstrates the possibilities for Brenda’s work to lead in a multitude of networked directions, from betweenity, to embodiment, to access.

Text transcript of Iwertz video:

[Next, Chad speaks.]

Articulating Betweenity had a big effect on my research and the approach I wanted to take to studying transcription. It was in that work I felt like Brenda specifically called attention to the many “in-betweens” that exist in both her presentation of Deaf and hard of hearing literacy narratives within the Digital Archives of Literacy Narratives and those narratives themselves. Early on in that piece she points to her work as a production created between both herself and “another guide,” who in this case was Julia Voss, and that naming of collaboration as a betweenity really affected me—I think in similar ways to how Tanya Titchkosky’s definition of access as “an interpretive relation between bodies” affects me (3). Both point to how access is interpretive, rhetorical, process-heavy, embodied. I think it can be tempting to think about access and captions (as a form of access, at least) as external from our bodies, as a cold technology that can be regulated and standardized and “right or wrong.” But Brenda’s work pushes me to think about captions as living, embodied forms of access that write themselves among the bodies that design, read, and study them.

“Follow the Love”: On Mentoring and Collaboration

“What women need are networks of allies, yes, but not just within academic institutions. We need to learn to make relationships beyond the familiar (especially when the familiar is so often unfriendly), to follow the love (one motto that we, Rachel and Brenda, used together in our shared writing program administrative work this year) wherever it leads and learn to make it work toward the kinds of change we want to see. Being open to and choosing love and friendship from a grounded position in an academic workplace, in wider networks of allies not assigned or officially ‘authorized,’ might get us even further outside of the one-to-one hierarchical power structures and get us, too, to make, see, and feel more substantive webs of support, comfort, and calm.” —Brenda Brueggemann and Rachel Gramer, No Day at the Beach: Women ‘Making It” in Academia, 311

A primary feature of Brenda’s work is its collaborative nature. Not only has Brenda mentored many graduate students and faculty members in our field, she is committed to jointly creating knowledge and publishing with others. The majority of her published work is collaboratively authored: of Brenda’s nine books, six are co-authored or co-edited. This is more than mere biography; it is a testament to Brenda’s career-long challenge to outmoded conceptions of how knowledge is constructed. As well-known collaborators Andrea Lunsford and Lisa Ede have written, “Since the mid-1980s ... we have been calling on scholars in rhetoric and composition, and in the humanities more generally, to enact contemporary critiques of the author and of the autonomous individual through a greater interest in and adoption of collaborative writing practices” (355-356). Brenda’s scholarship and administrative practice throughout her career have answered Lunsford and Ede’s call to move beyond the single authored text as the ideal, which we approach as a model of interdependence.

In her collaborative work, Brenda accounts for the labor of knowledge creation in its many forms, which is perhaps nowhere better exemplified than in her acknowledgement of her webtext designer for Articulating Betweenity: Literacy, Language, Identity and Technology in the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing Collection. As Iwertz mentions in his artifact, Brenda explicitly calls the reader’s attention to her nearly invisible collaborator on the webtext: “You will see (and maybe even ‘hear’) me throughout this textual road trip as we traverse some states of ‘Modern Deaf-World.’ You won’t much see—or hear—my collaborator and designer, Julia Voss. But she is the backseat driver without whom no destinations would have ever been reached.” While many authors might cling to distinctions between writer and designer in order to claim writerly autonomy, Brenda recognizes the different contributions that many parties bring, regardless of how they have been traditionally coded in academia.

As the artifacts throughout this retrospective illustrate, Brenda has been a mentor to many people in rhetoric and composition. Many of us, and we include ourselves in this statement, have benefitted immensely from Brenda’s guidance and example of how to carve out a life in academia that is true to our own identities. Even as we may have experienced being mentored by Brenda as the typical one-on-one apprenticeship (picture the ASL sign of one index finger held up in front of the other index finger), Brenda has questioned this traditional definition and pushed the field to consider mentorship as mutually beneficial and, in some cases, more of a network than an apprenticeship. In her 1997 article, On (Almost) Passing, Brenda shares the story of collecting case studies from D/deaf students as Gallaudet University, and recalls the personal impact that these relationships had on her, even when she was in the position of “model and mentor” for a struggling student, Lynne (654). Brenda recalls the “pain of trying to be Lynne’s inspiration, her role model, her fetish, her whatever” when she herself felt she “could barely pass as either clearly and securely ‘D/deaf’ or ‘H/hearing’” (655). This story breaks the traditional and too-tidy mentoring narrative we usually get, and it shows the complexity of the mentoring relationship and its effects that can move in multiple directions. As Brenda so eloquently describes her mentor-mentee relationships at Gallaudet: “We were trying out our mirrors on each other, trying to see if these multiple mirrors would help us negotiate the difficult passages we always encountered in relationships” (651). At the very least, these mirroring moves operated in two directions, if not in a network.

Much more recently, Brenda has shared insights on mentoring in her 2017 co-authored essay, No Day at the Beach: Women ‘Making It” in Academia, in which she claims the mutual benefits of mentoring relations. She explains that in a truly engaged relationship, the roles can swap, and “the mentor learns things she didn’t even know ... because of a mentee’s sometimes simple, sometimes profound questions of in-need-of-mentoring situation” (312). This example illustrates that especially as mentors and mentees work together on administrative projects, the apprentice model does not quite fit, but could be better described as a “recursive and toggling relationship ... within the space of learner-knower” that “swap[s] out positions as bow-paddler and stern-paddler from time to time” (313). And Brenda and her co-author of this essay, Rachel Gramer (who has contributed mightily to this retrospective, as well), encourage this concept of mutual mentoring to be expanded beyond a one-on-one relationship, and instead reimagined as a network of support and interdependence that extends beyond one’s own department and even discipline. We cherish the quote from Brenda and Gramer that begins this section because it urges such network creation to be based on love or tapping into that “felt sense” (365), as Sondra Perl calls it, that tells us where we should be headed and what will bring us joy in our work. We also understand Brenda’s unique mentorship style as her contribution to feminist ways of nurturing our colleagues and friends.

Artifacts on Mentoring and Collaboration

Chad Iwertz, in his video artifact that follows, describes the ways in which Brenda’s generosity with her time and expertise has helped him craft his dissertation project in rhetoric and disability studies. He expresses his gratitude for Brenda’s mentorship and personalized feedback on his ideas.

Text

transcript of Iwertz video:

[Now, Chad speaks.]

I feel like the moment I set out to do work in captioning for my dissertation, Brenda was there wanting to chat. We ended up meeting during the chaos that is DMAC (the digital media and composition institute at Ohio State), and even given the fast-paced nature of the institute, she met individually with me to talk about my work, her work in rhetorical captioning, and the stakes of real-time captioning. I’m actually still trying to find a better title than the one she originally gave me, but I think that’s going to be impossible. How do you find a better title than, “The Sound of Light”??

[The words appear like fireworks.]

Brenda has many gifts, and she brings them to her generosity in working with new scholars in ways that I hope I can continue on as my career continues in the field.

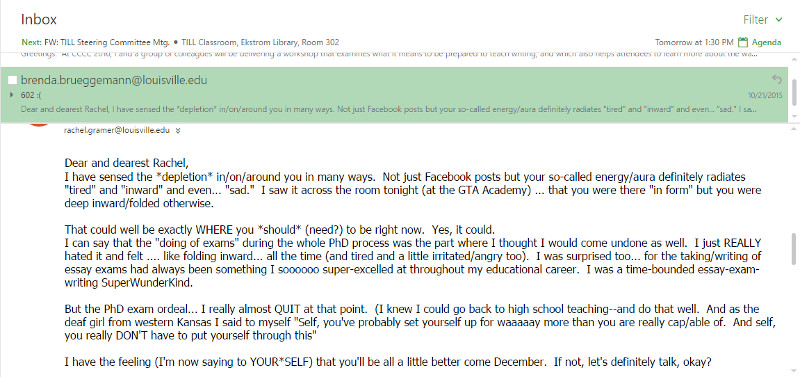

Rachel Gramer, in a textual artifact, also shares about Brenda’s generous mentorship. Gramer focuses on what she calls “a Brenda Email,” in which Brenda emanates warmth and love even via email, a mode that is usually considered professional at best and cold at worst. But, as Gramer puts it, Brenda takes email to “a whole other level.”

Open for: Doubt and Speaking Doubt

This last story starts with an email—and stays open for doubt. The first semester of my administrative work with Brenda was also the Dreaded Semester of Doctoral Exams (three, to be specific) for me. And when I emailed Brenda to say I would not be attending her practicum course that week (which I was observing to inform my dissertation study), she wrote back a reply that is representative—not a word I use lightly or typically at all—of a Brenda Email, taking your email to a whole other level, and of the kind of Seeing and Openness that I know I can always use more of in my everyday academic interactions:

The email reads:

Dear and dearest Rachel,

I have sensed the *depletion* in/on/around you in many ways. Not just Facebook posts but your so-called energy/aura definitely radiates “tired” and “inward” and even ... “sad.” I saw it across the room tonight (at the GTA academy) ... that you were “in form” but you were deep inward/folded otherwise.

That could well be exactly WHERE you *should* (need?) to be right now. Yes, it could.

I can say that the “doing of exams” during the whole PhD process was the part where I thought I would come undone as well. I just REALLY hated it and felt ... like folding inward ... all the time (and tired and a little irritated/angry too). I was surprised too ... for the taking/writing of essay exams had always been something I soooooo super-excelled at throughout my educational career. I was a time-bounded essay-exam-writing SuperWunderKind.

But the PhD exam ordeal ... I really almost QUIT at that point. (I knew I could go back to high school teaching—and do that well. And as the deaf girl from western Kansas I said to myself, “Self, you’ve probably set yourself up for waaaaay more than you are really cap/able of. And self, you really DON’T have to put yourself through this”

I have the feeling (I’m now saying to YOUR*SELF) that you’ll be all a little better come December. If not, let’s definitely talk, okay?

I received, processed, replied, and sat with this email the following morning; and I still (clearly) revisit it, sometimes in my interactions with other grad students. I have passed on this message to a friend/peer mentee: Even Brenda Brueggemann “really almost QUIT” during the “exam ordeal.” That statement is always met by an embodied response, an avalanche of tears waiting to be released or a drying up of those already flowing, usually accompanied by vigorous nodding and sincere laughter. This is what it is. It makes Everyone almost quit.

But what sticks with me and opens me up is the memory of reading this line: “And as the deaf girl from western Kansas, I said to myself, ‘Self, you’ve probably set yourself up for waaaaay more than you are really cap/able of. And self, you really DON’T have to put yourself through this’” (all of which is an open parenthetical that never closes—appropriately so). While the tone and tenor of the whole message (abridged here) could be read as infused with hope and belongingness (and those are both present), I still also read and remember this exchange as being full of, and open for, deep-seeded doubt and its partner, quiet certainty. But not about cap/ability to achieve and meet the PhD benchmarks—because despite Brenda’s own memory of doubting her cap/ability, she is clearly telling this story from a removed temporal and professional position from which she can look back and know that, of course, she was cap/able. She was living out an imposter syndrome story at the time—as we all do, were, are. But in retelling her story, I felt encouraged to live out another story: one in which I, too, got to say, “self, you really DON’T have to put yourself through this”—because maybe “this” just isn’t worth it even though you are cap/able of doing it. Because if Brenda Fucking Brueggemann didn’t think she was cap/able, then maybe this culture that structures in such continual doubt—even as it tries to support people in learning and growing as professionals—isn’t for you. And you, too, could go back to high school teaching and do that. So. Well. And that would be okay, too.

Of course, I’d like to say that I internalized Brenda’s email and terminated my relationship with imposter syndrome; but my revisiting of, my need to revisit, her message betrays that lie. Yet I still get to pay forward a story not beholden to the narrative groove of imposter syndrome: not just that we all have doubts, or that we all consider quitting at some point, but that we “really DON’T have” to do this academic life if we don’t want to put ourselves through it. And while this is certainly not new/s, it bears repeating and articulating both in our scholarship and in our everyday interactions with others, particularly newcomers. With an emphasis not on cap/ability, but on choice. Academia is a choice, as is doctoral education, and there should be no shame in choosing otherwise. This requires a different kind of openness for doubting than the imposter syndrome authorizes, the kind of openness for doubt even with a certainty of cap/ability, which this message of Brenda’s (along with so many others in my inbox) modeled in its vulnerability and honesty, sparked by her own seeing, sensing, and speaking into being. —Rachel Gramer

Disrupting Balance and Binaries

“On several pages in Women’s Ways of Making It in Rhetoric and Composition, I narrate the way that I worked with my spouse at that time, also an academic, to ‘balance’ our workloads while also sharing and raising two young children. Yet as I read that back now, I realize that, while I worked then to carefully narrate a Fairy Tale of Balance ... it was really not so. The tale was fractured from the outset, but I wanted, desperately, to imagine and render it as one of balance—to make balance BE the story that said, ‘I AM in balance.’ ... And from this decade-past vantage point, I must also then imagine and question at large: How many of us academic women tell ourselves the fairy-tale about the ‘balance’ in our lives? And what are the perceived advantages—and risks—in doing so? What is at stake in be/am-ing balance as The Thing We Must (we must!) achieve? Is ‘balance’ an act of ‘narrative normalcy’—an overdetermined narrative—that also limits other stories we might (and maybe even should) tell?” —Brenda Brueggemann and Rachel Gramer, No Day at the Beach: Women ‘Making It’ in Academia, 307-8

Throughout her scholarship, Brenda has rejected binaries in favor of triangulation that can lead to a deeper, more realistic understanding of any situation. Nowhere is this more true than in her challenge to the myth of balance between our personal and professional lives. The myth that balance means keeping binary forces in harmony and that it is attainable causes pain for many academics, particularly women. The quote beginning this section demonstrates Brenda’s own grappling with the “overdetermined balance narrative” as the ultimate “good” (308). In Brenda and Gramer’s essay, they encourage other ways of imagining a full professional and personal life by sharing examples of senior scholars in rhetoric and composition who enact balance differently. While Patricia Bizzell separates her home and work life clearly, Cheryl Glenn writes from home in the mornings and goes to campus in the afternoon; in other words, Glenn begins her day at home with her work (305-306). Cindy Selfe adopts what Brenda and Gramer describe as a “work-at-home and home-at-work approach,” about which Selfe freely admits “my work and my life are the same thing” (306). In a recent talk Elizabeth heard Brenda deliver about her piece, “No Day at the Beach,” she noted that she used to feel guilty for working so much when she had young children. She compared this guilt to an albatross that she carried around, but she shared that now she realizes work as a source of happiness and fulfillment too. She mentioned how much she loves the daily discussion and writing that she engages in, and the work/leisure binary simply does not apply. Those who have worked with Brenda likely see the joy she takes in her everyday tasks, as we do, through the whimsy she weaves into even the most mundane administrative tasks. Working near Brenda is a guarantee that a candy bowl and some fun, brightly colored office supplies are nearby.

Brenda’s refusal to accept the “fairy tale of balance” as the personal and professional having equal weight in one’s life is reminiscent of a move she makes throughout her scholarship. As we mentioned earlier in this essay, her interest in betweenity and in “working the hyphen” take up similar inquiries. As Brenda does in her critique of balance, she uses the complexities of identity to disrupt false dichotomies or roles that are thought to be in conflict, such as mother/professor or disabled/rhetor. She has masterfully shown in An Enabling Pedagogy that disability often shows these either/or categories to be false: “disability always begins (and probably ends, too) in its ambiguity, in its indeterminate boundaries” (793). When we understand that disability studies makes impossible any clean separation between ability and disability, we also see this same myth at work in other areas of our lives and our profession.

While some parts of Brenda’s personality may not come through in her scholarship, they characterize her approach to mentoring, teaching, writing, and administration. Her buoyancy, exuberance, and thoughtfulness deeply imbue these activities. In her own words, Brenda loves her work, and the artifacts below show some of the ways she infuses her days with joy that affects others.

Artifacts that Bring Joy and Love to the Academic Workplace

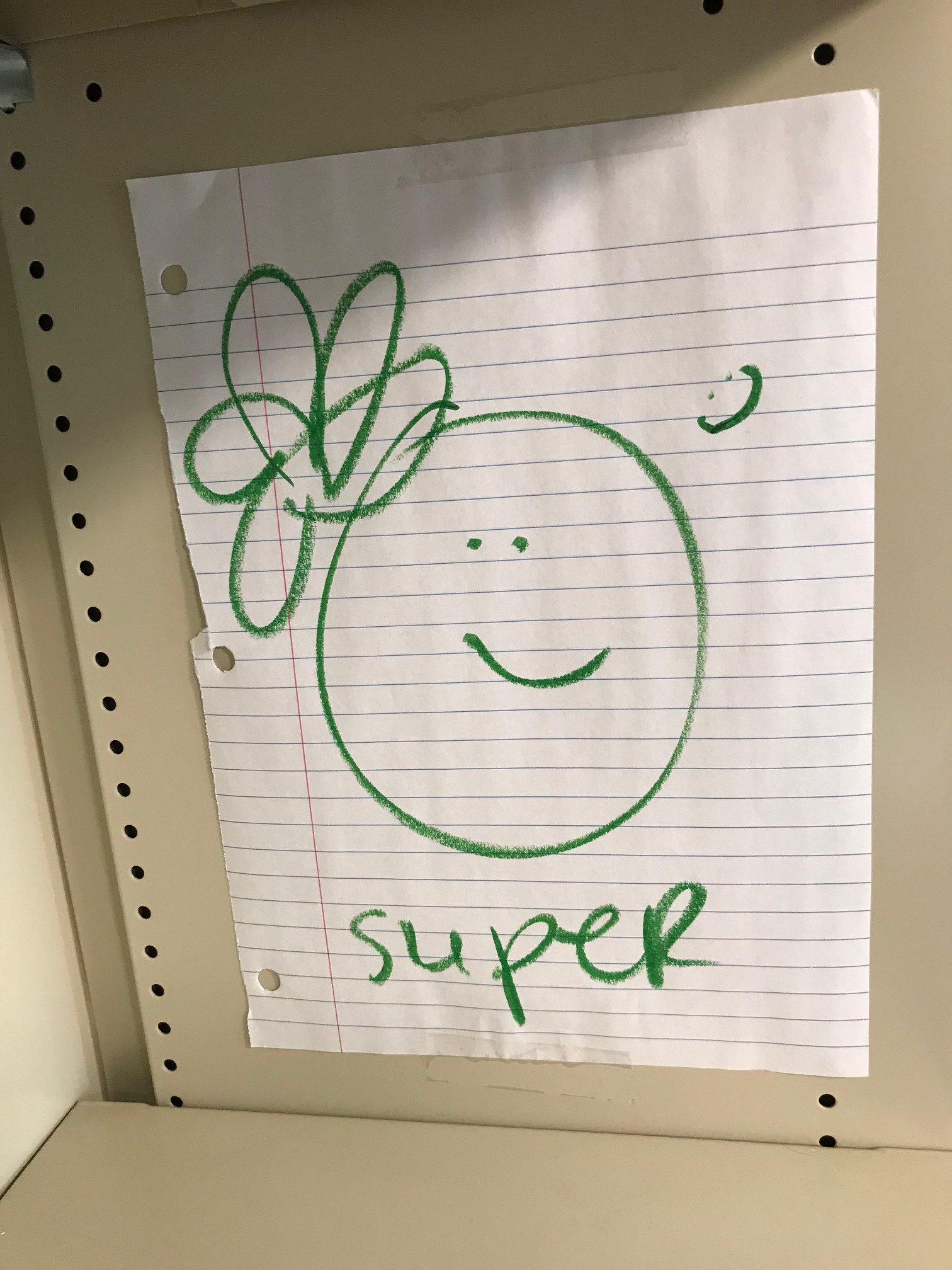

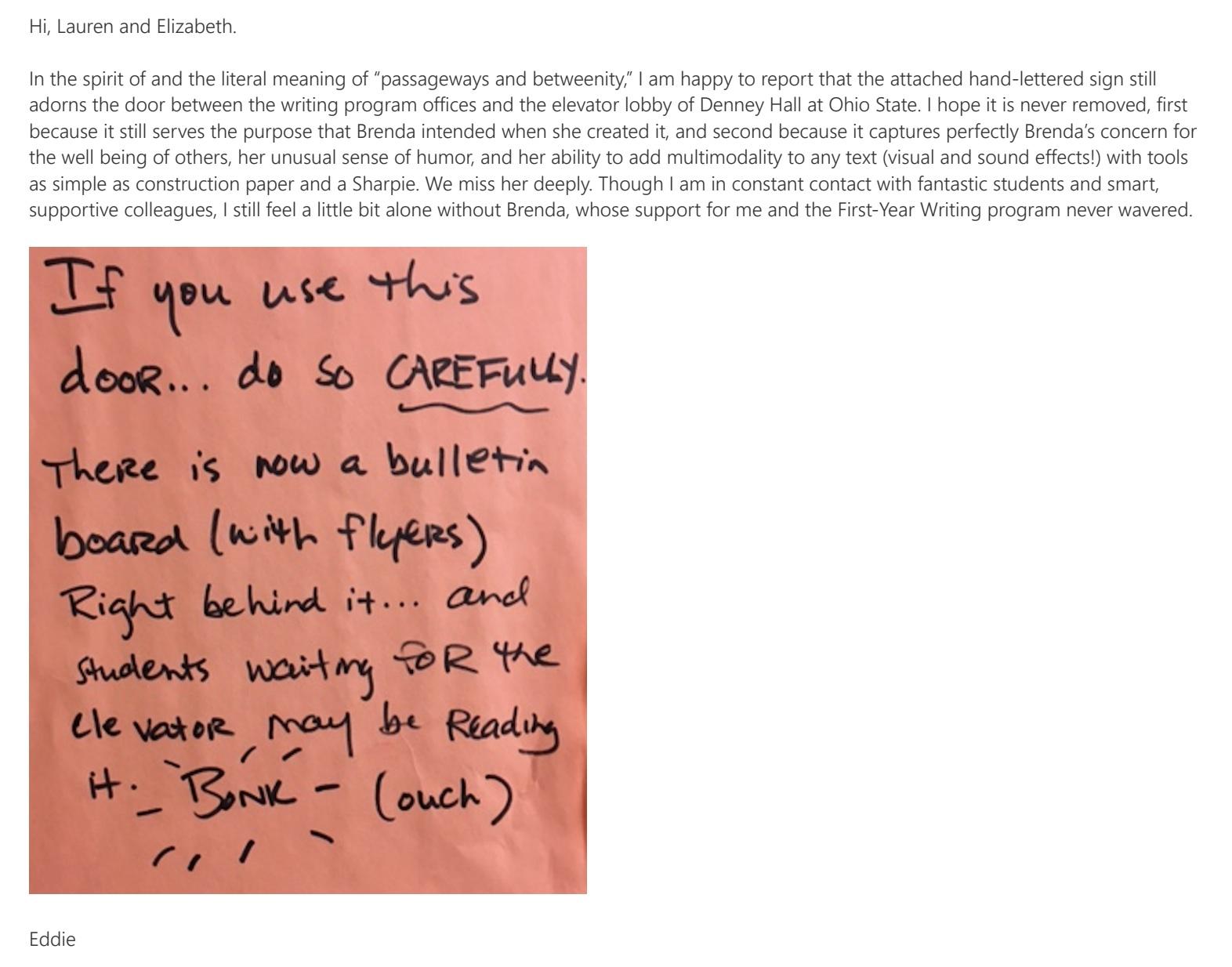

The first two artifacts are pictures from Elizabeth’s office that feature a drawing Brenda made for her years ago that she keeps as a reminder of Brenda’s positivity. It is a large smiley face with a flower and smaller smiley face to the side, with the word “super” written below. The second artifact is Elizabeth’s own candy dish, inspired by the one Brenda keeps in her own office. Finally, the third artifact is from Eddie Singleton, who cherishes the humorous and thoughtful sign that Brenda made years ago that still hangs on a door near his office.

The email from Eddie Singleton reads:

Hi, Lauren and Elizabeth.

In the spirit of and literal meaning of “passageways and betweenity,” I am happy to report that the attached hand-lettered sign still adorns the door between the writing program offices and the elevator lobby of Denney Hall at Ohio State. I hope it is never removed, first because it still serves the purpose that Brenda intended when she created it, and second because it captures perfectly Brenda’s concern for the well being of others, her unusual sense of humor, and her ability to add multimodality to any text (visual and sound effects!) with tools as simple as construction paper and a Sharpie. We miss her deeply. Though I am in constant contact with fantastic students and smart, supportive colleagues, I still feel a little bit alone without Brenda, whose support for me and the First-Year Writing program never wavered.

The sign reads:

If you use this door ... do so CAREFULLY. There is now a bulletin board (with flyers) right behind it ... and student waiting for the elevator may be reading it. BONK (ouch)

Dwelling in Wonder

“Yet we wonder. And that wonder is what makes us human. We fear that having a conversation about something like what Georgina can and can't see, what Brenda can and can't hear, what Rosemarie can and can't do is just too personal in a classroom space. Yet nothing should be more important in a classroom than that wonder.

“That wonder broke open in a recent class I taught too; finally one day they really wanted to talk about how I actually did lip read. ‘How do you do that?’ one student finally asked. It came up with one book we were reading, What's that Pig Outdoors—an autobiography by former Chicago Times book review editor, Henry Kisor. And when the wonder cracked open I felt, like you Georgina, sort of uncomfortable-how much of this do I want to give? To tell the truth, I don't fully know either how I do it! And it's not really what we were supposed to talking about either—‘Literary Analysis of Lipreading’ was not on the syllabus for that day.” —Brenda Jo Brueggemann, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and Georgina Kleege, What Her Body Taught (Or, Teaching about and with a Disability): A Conversation, 15

Wondrous, Whimsical Artifacts

The passage above, from a published “conversation” between Brenda, Rosemarie Garland-Thomson, and Georgina Kleege, highlights the centrality of wonder—to disability, to pedagogy, and to humanity. Wonder, in its deep and wide reach, in its push for complexity and nuance, and in its resistance to the idea of an “answer” or “ending” seemed like the most appropriate place to conclude this essay. Appropriate, of course, because we hope that this conclusion will not be the end of your visit to Brenda’s work or your exploration of disability studies. Instead, we hope the Museum of Brenda offers a space for visitors to dwell, to acknowledge disability, to ponder further questions, and to move toward fuller conversations.

We reverse the order we have been following in other sections as we conclude this retrospective. We first offer wondrous, whimsical artifacts, and then we (Elizabeth and Lauren) move to some brief synthesizing remarks to wrap up your visit to the Museum of Brenda.

The first artifact is a video from Ryann Patrus, who discusses Brenda’s mentorship and generosity. Ryann notes that Brenda offered her a framework for understanding her own experience, stating simply, “I wouldn’t be here without her influence.” Patrus’ articulation of this influence gets at one powerful result of instilling and promoting wonder; as also demonstrated in the email she sent to Rachel Gramer, this wonder is part of mentoring others, bringing new scholars into the field and helping them understand the value of their own experiences.

Text transcript of Patrus video:

[Now, Ryann speaks.]

Brenda's work has been incredibly influential in my development as a scholar and activist. She exposed me to the world of disability studies through a presentation on Deaf culture she put on at Antioch College where I completed my undergrad. Her talk helped me name the kind of work I wanted to do, disability and Deaf studies. Brenda presented me with a framework for understanding my own experience and the history of a community I was only just beginning to identify with. I credit her with ushering me into disability activism and disability studies scholarship, I certainly don't believe I would be in a disability studies program without her example. And she also helped to establish this program at OSU. So I literally wouldn’t be here without her influence. Thanks, Brenda!

The second artifact comes from Rachel Gramer. It is brief textual narrative that discusses the power of celebration and whimsy, wondrous aspects that are all too rare in academia, yet Brenda centers them, especially in her administrative work. Gramer’s narrative also includes a photo collage that visually illustrates Brenda’s commitment to wonder in her day-to-day professional life. The collage features a selfie of Brenda and Gramer smiling joyously with stuffed animals; a cake complete with sparkling unicorns; Brenda and a group of graduate students hovering over a projector to screen digital documentaries; and a set of red and black buttons with fun (and wondrous!) slogans like “Comp magic is everywhere!”

Open to: Collaboration and Celebration

When I began my doctoral education, I didn’t feel I could possibly be ready for administrative work before (or perhaps even after) I graduated; by my second year in the program, I couldn’t imagine not engaging in the intellectual, logistical, and community-building work of administration done well. Before I officially entered the position, Brenda and I had worked out a plan for a professional development event to open the following year’s orientation. During the entire process of this event, the Digital Composition Colloquium (DCC), from planning to end-of-year reflection, Brenda modeled—and I got to see and experience—being an administrator open to collaboration and celebration. And just as importantly, she shared her own articulation of the meaningfulness of that event, which caught me entirely by surprise.

The DCC was a 2-day intensive event that brought together 40 new and experienced writing instructors in our program to create digital texts and work together to discuss how to incorporate, assign, and assess digital projects in their first-year writing classrooms. With Brenda’s support as then-Director of Composition, the DCC was co-designed and led by a team of five doctoral students who wrote course syllabi and assignments, facilitated discussions and digital editing workshops, and created a website to deliver teaching materials and resources for digital composition. In just two days of the DCC, writing instructors participated in discussions on multimodal texts, assignments, and assessment; learned about copyright and Creative Commons licensing; and engaged in hands-on practice in using digital tools and searching for online resources. Even more importantly, participants created a 1-minute video in response to a (then) new (for us) program assignment that many of them were about to introduce in their writing courses that year: the Concept in 60 (C60) multimodal video project (with many thanks to Ohio State, the Digital Media and Composition Institute team, and Cindy Selfe who was our DCC visiting scholar). The Louisville version of the C60 specifically guided participants (and would guide their students) to create a video about a cultural diversity or community issue that matters to them; and instructors noted (in circulating conversation and by survey) that making a video themselves was both an expected and unanticipated challenge and that the greatest benefit (outside of this making) was collective struggle and working through struggle with other instructors in the time-space of the DCC.

One of Brenda’s self-appointed tasks throughout this event was to structure in celebration and whimsy for the whole group—not standard protocol for often weighty, not whimsical professional development. There were pins that proclaimed we were “Doin’ It Digital,” there was BBQ, and there was much-needed laughter and celebrating of the videos people created during a two-day crash course in digital production. (And of course Brenda brought the whimsy in addition to advocating for the value and financial support of the event and acting as mentor for the heavier/headier stuff of digital composition-meets-administration-and-collaboration for the five graduate student leaders—no small feats to be sure.)

Looking back now, nearly two years later, I can see that the DCC seems like—and was—a big event in my doctoral education and in the education and professional development of many people in our program. But by the end of that year, it had become as I imagine most things becoming for us as we plod through another academic year: something that happened, that was over, that I was about to assess from a removed temporal distance. Until Brenda’s composition “going away” party before she departed for Connecticut. Again, there was whimsy and celebration (and of course, unicorns, magic, and cake)—but there was also articulation of meaningfulness that actually stopped me from glossing over my own collaborative/administrative/meaningful work and took me by surprise, when Brenda said that she considered the DCC to be a highlight not just during her time at Louisville but of her career. Even today, the imposter syndrome in me wants to say I’m sure that’s not true, she was being kind, it was good but it wasn’t that good. But the narrative researcher in me is louder and says This is the story she spoke into being in that moment; and now you can speak a story into being around it, too. And the story I am (still) telling is that events don’t just happen or end; but they do need people to celebrate them, to articulate their meaningfulness afterward in the presence of others who are perhaps waiting to be taken by surprise. Brenda’s openness to collaboration is not unique—though it is valuable and not to be taken for granted as a “given” among scholars in our field; her openness to visible celebration is equally valuable and a perhaps less common trait; and her openness to articulating what is meaningful in deeply personal and professional ways in the presence of others is an administrative, feminist, and human model that I hope I can enact and keep surprising people with in my next position as assistant professor and associate director of first-year writing. —Rachel Gramer

Conclusion (But Not Really)

Ultimately, nearly all of Brenda’s work, in both her publications and her many personal interactions with colleagues, pushes rhetoric and composition (and many other related disciplines) toward an embrace of wonder. In “What Her Body Taught (Or, Teaching about and with a Disability): A Conversation,” Brenda and her long-time collaborators and friends Rosemarie Garland-Thomson and Georgina Kleege ruminate on what it means to teach as disabled women. They each discuss ways that, in some instances, they want their disabilities to be avoided in the classroom, or at least not be the topics of constant prying questions. At the same time, as we discussed earlier in this essay, disability can provide insight, and it is thus often productively at the center of both the content and processes of the courses these three women teach.

As Brenda emphasizes in her comments that begin this section, the goal when thinking about disability, in the classroom, and otherwise, can indeed be wonder. To silence discussions of disability, or discourage questions, can stigmatize disability further or drive students toward what Garland-Thomson calls, in this same essay excerpted above, “mea culpas” in relation to disability. That is, students never ask about her disability—seemingly actively avoiding it, even when it does connect to the course. But then they later turn in apologetic writing about how they had never thought about the “suffering” of disability, and they will now “do better” when it comes to disability (16-17). Brenda, Kleege, and Garland-Thomson explain how such well-intentioned apologies miss the point, as these mea culpas subscribe to dominant and non-critical narratives that universally depict disability as a condition to be pitied.

Instead, then, a space of wonder can be created and fostered. A space to open up thoughtful and meaningful dialogue about disability, what it means, how it is experienced and embodied, as well as the insight it brings to the classroom and far beyond. As Brenda articulates in the passage above about lip-reading, this can be a difficult space to establish, hovering between this problematic silencing and avoiding of disability and overly personal and off-topic questions about it. But Brenda brings it back to wonder as a potential answer, a middle ground in which to dwell. Brenda states, “Yet nothing should be more important in a classroom than that wonder” (15).

We hope, dear readers, that this retrospective, this all too brief visit into the Museum of Brenda, instills some of that wonder in you.

Acknowledgments: The authors would like to thank all of the wonderful folks, listed as contributors, who helped build this piece through their memories, narratives, and artifacts, as well as feedback and insight they provided about the retrospective along the way. We also thank Annika Konrad, Stephanie Kerschbaum, and Elisabeth Miller, who were supportive, flexible, and informative as the retrospective came together (and sometimes more slowly than planned!). Finally, we especially thank Brenda Brueggemann for her support and comments as we drafted this retrospective. In True Brenda Style, she was the best collaborator we could ask for.

Notes

-

For instance, Lauren notes that she assigns Brenda’s essay “On (Almost) Passing” essay in every course she teaches; it is always applicable, relevant, and beloved by students. (Return to text.)

-

See page 8 in Lend Me Your Ear. Brenda states, “Uncertainty loves a hyphen. Rhetoric does too.” She explains herself as “working the hyphens,” personally and professionally; Brenda cites this particular phrase as originating in anthropologist Michelle Fine’s work.

Brenda also notes, when reviewing this article, that she first wrote about “occupying the hyphen” in the context of qualitative research. She discussed being “between still-life and between participant-observer.” See:

Still-Life: Representations and Silences in the Participant-Observer Role. Ethics and Representation in Qualitative Studies of Literacy. Eds. Peter Mortensen and Gesa E. Kirsch. Urbana: NCTE, 1997, pp. 17-37.

Works Cited

Anderson, Dan, et al. Integrating Multimodality into Composition Curricula: Survey Methodology and Results from a CCCC Research Grant. Composition Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, pp. 59-83.

Balliff, Michelle, et al. Women’s Ways of Making it in Rhetoric and Composition. Routledge, 2008.

Brueggemann, Brenda Jo. Articulating Betweenity: Literacy, Language, Identity and Technology in the Deaf/Hard-of-Hearing Collection. Stories That Speak to Us, edited by Lewis H. Ulman, Scott Lloyd DeWitt, and Cynthia L. Selfe, Computers and Composition Digital P/Utah State UP, 2013, http://ccdigitalpress.org/stories.

---. Deaf Subjects: Between Identities and Places. New York UP, 2009.