Composition Forum 43, Spring 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/43/

Technology Professional Development of Writing Faculty: The Expectations and the Needs

Abstract: Not only is the current scholarship on technology professional development (TPD) of writing faculty at the periphery of Writing Studies, there doesn’t seem to be a clear conceptualization of the scope of knowledge and skills needed to teach writing with technology critically and productively. In this study, I address these issues using two research questions: a) What are the teaching with technology-related expectations for college writing faculty as stipulated in 11 CWPA, CCCC, and NCTE position statements? b) What are the characteristics of technology professional development programs, as identified in these statements, that train teachers to meet these expectations? The deductive analysis of these statements reveals that the three organizations have collectively stipulated three levels of technology-related expectations for writing faculty as well as the fundamental characteristics of an effective TPD program that would train in-service faculty to meet these expectations. Based on findings of this study, I argue that the institutional responsibility to provide writing faculty with robust TPD opportunities is not only professional but ethical as well.

Background and Introduction

When the task force charged with revising the Writing Program Administrators Outcomes Statement (hereafter WPA OS) 2.0 sought writing faculty and writing program administrators’ (WPAs) input on the statement revision, two concerns surfaced during the discussion and feedback: the preparation of teachers with varied access to digital technologies and the growing reliance on contingent faculty in teaching first-year writing (FYW) courses (Dryer et al.). The task force hoped that issuing the WPA OS 3.0 would spark a multitude of practices of teaching writing, one of which is professional development (PD) of writing faculty. Given that one of the concerns has to do with technology access, it is safe to infer that the PD Dryer et al. hoped would happen includes training on teaching with technology. John Bruce Francis defines faculty development as the “institutional process which seems to modify the attitudes, skills, and behavior of faculty members toward greater competence and effectiveness in meeting student needs, their own needs, and the needs of the institution” (720). If applied to technology professional development (TPD), Francis’s definition means that TPD is not limited to enhancing the technical skills of using certain technologies; instead, it extends to teacher attitudes and perceptions of using technology, which requires discussion of the theories and pedagogies of teaching with technologies. What’s more, Francis’s definition connects faculty training to the ability and possibility of satisfying student needs and success while meeting both institutional goals that typically include student success and retention, and departmental and programmatic goals of achieving student learning outcomes. Therefore, an effective TPD program should comprise “intentional, in-service activities overtly planned to improve various aspects of teaching performance” (Condon et al., 5).

The scholarship on TPD of writing faculty is surprisingly scarce. The available research has focused on the training of graduate students on teaching with technology through course offerings (Blair; Hauman et al. Writing Teachers) and TA mentoring and practicum (Blackmon and Rose; Reid, Estrem, and Belcheir). In other words, there is no sufficient research (empirical or conceptual) on TPD of in-service writing faculty in post-secondary institutions. Additionally, the current scholarship doesn’t seem to have a clear-cut conceptualization of the expected knowledge and skills that writing faculty need to teach technology-rich FYW curricula with technology-related student learning outcomes.

In this empirical study, I address these two serious gaps in the field’s scholarship and my purpose is double-fold: a) to determine the scope of teaching writing with technology expectations for college writing faculty and b) to map out the characteristics of effective TPD programs that train faculty to meet these expectations and to be able to teach writing with digital technologies effectively. I define effective teaching with technology to include critical and productive use of technology in the writing classroom: critical teaching with technology is bound by context and learning objectives (Takayoshi and Huot), and productive teaching with technology means to achieve learning outcomes and student success. In the following sections, I establish the need for TPD programs for writing faculty from the current scholarship, outline my research methods, present and discuss my findings, and propose directions for future research.

Where We Stand (a.k.a. Review of Current Literature)

In their 2006 survey study Integrating Multimodality into Composition Curricula: Survey Methodology and Results from a CCCC Research Grant, Daniel Anderson and a team of leading digital writing scholars examined six areas related to multimodal composing. In the section on PD in the survey, there were questions about teacher access to resources and the “efficacy and extent of technology training” (64). All survey respondents indicated that they were “primarily self-taught” on implementing and assessing multimodal composition with disparate levels of support from their institutions, friends and colleagues, or PD events at other institutions (73). Anderson et al. also found that:

Teachers who assigned multimodal compositions, among our survey respondents, reported needing increasingly effective and appropriate professional development opportunities. Professional development workshops offered by institutions and departments to the survey respondents provided hands-on practice with specific software tools, but little help in conceptualizing multimodal assignments, assessing student responses, or securing the hardware needed to undertake such assignments. (79)

These responses, though limited to multimodal composing as one form of teaching writing with technology, point to two main issues: access to resources and the lack of conceptual and pedagogical knowledge about effective integration of emerging technologies. These concerns are not peculiar to participants in Anderson et al.’s study or to Writing Studies alone as they have been shared by scholars across disciplines. Kimberly Lawless and James Pellegrino argue that many PD programs in Education haven’t been “guided by any substantial knowledge base derived from research about what works and why with regard to technology, teaching, and learning” (576). An interpretation of this shortcoming in PD programs comes from Pinya Mishra and Matthew Koehler who note that the common view of technology is that it is independent from content and pedagogy and requires separate type of learning that focuses more on skills rather than on knowledge (1025). That binary view may explain why teachers receive workshops on using some software or hardware in isolation from the pedagogy or the content they teach even though Bruce Joyce and Beverly Showers identify “theoretical basis” as the common denominator in all approaches to effective TPD programs (qtd. in Schrum 84).

Anderson et al. conclude that “the accessibility of professional development opportunities” is among an array of factors that influence the integration of multimodal composing in the writing classroom (79), thus implying that unless higher-education institutions invest more in the TPD of faculty, teaching with technology becomes more of an idiosyncratic choice made by a few invested teachers than a curricular or programmatic need. This situation leaves us to wonder about faculty whose prior academic training, scholarly and teaching interests, employment status (tenure-track or non-tenure track), or financial ability doesn’t allow for pursuing PD opportunities outside their home institution. And what if these faculty are tasked to teach a technology-rich curriculum?

Alice Johnston Myatt and Ellen Shelton provide an answer to this question. When the writing program at their university adopted a multimodal assignment as part of the writing curriculum, the university provided support for teachers to better implement that assignment in their classes. Myatt and Shelton cite the “profound influence” of a workshop on multimodal composing offered by Dickie Selfe on writing teachers in their program even years after attending the workshop (195). Teachers at their institution particularly thought the “suggestions and practical modeling” of multimodal composing have enhanced their teaching. Myatt and Shelton’s account of that experience demonstrates the necessity and positive outcomes of offering tailored TPD opportunities to writing faculty prior to charging them with teaching a technology-rich curriculum or achieving technology-related learning outcomes. Although Myatt and Shelton don’t elaborate on the content offered during Selfe’s workshop, the tailored TPD program they describe is a good example of programs that “go beyond the functional use of new media technologies to discuss the pedagogical choices available through these new technologies” (Mina 14). My proposition elsewhere indicates that writing faculty need more than technical skills to be able to teach writing in its broad definition that includes “digital production” (CCCC Strategic Governance Vision Statement). But what do writing faculty in fact need to teach writing in its broad definition? Unfortunately, there doesn’t seem to be a singular clear theoretical conceptualization of the expectations of knowledge, skills, and behaviors writing teachers should have in order to effectively teach writing with digital technologies. Such expectations should ideally inform the design of any TPD program.

After the WPA OS 3.0 was published, TPD programs that would train writing faculty on teaching writing with technology were expected to follow the approval and adoption of the statement in many writing programs across the country. Whether this type of faculty development took place but was under-researched, or whether the prolonged academic publication cycle has hindered a more timely publication of such research, or whether it went under the radar of writing scholars, we simply don’t know. Because of the scarcity of scholarship and the absence of such details, I looked for answers in a corpus of position statements and resolutions issued by the three major professional organizations: the Conference on College Composition and Communication (CCCC), the National Council of Teachers of English (NCTE), and the Council of Writing Program Administrators (CWPA). I was aware of the varied exigences of producing these position statements and that their purpose was not closely related to teaching writing with technology or technology training of writing faculty. For example, the purpose of the NCTE Definition of 21st Century Literacies is to introduce a different definition of “a literate person” to include more complex “abilities and competencies” than traditional literacy given the constant and rapid advancement of technologies in the 21st century. Yet, I wanted to take advantage of the guidelines and stipulations in these position statements and to analyze them to see if collectively, rather than individually, they would provide a precise portray of technology-related expectations and any guidance on the type and form of PD programs that train teachers to teach with technology. On the one hand, I repurpose these statements beyond their original goal; on the other, I put these statements at the heart of research, a goal I dare say the three professional organizations would support.

Through examining this corpus of position statements, I wanted to answer the following two research questions:

-

What are the teaching with technology-related expectations for college writing faculty as stipulated in 11 CCCC, NCTE, and CWPA position statements?

-

What are the characteristics of technology professional development programs, as identified in these statements, that train teachers to meet these expectations?

Methodology

Study Design

This is an empirical qualitative, document analysis study of a corpus of position statements (hereafter statements). Glenn Bowen defines document analysis as “a systematic procedure for reviewing or evaluating documents” (27) that starts with finding, selecting, and appraising documents. Finding data for this study was the easiest of the three stages; data came from the statements issued by CCCC, NCTE, and CWPA. Initial appraisal of the 40 statements collected based on their title indicated that they vary in length, context, purpose, and target audience. These mixed characteristics made it imperative to set up clear criteria for selecting the statements to be used as source of data in this study.

Sampling and Data Selection

Criterion-based sampling means setting a list of relevant criteria then selecting the data that meet these criteria (Geisler). Using their titles, I collected a pool of 40 statements from the three organization websites. To set up the selection criteria, I started with a list of the constructs in my research questions as search keywords. Each statement had to include a minimum of two of these keywords listed in Table 1 to be considered for inclusion in the study corpus.

The second criterion was the date of issuing or updating the statement. Using Hauman et al.’s (The Language of Technology) timeline of the word “technology” in a larger pool of statements, I was able to exclude the ones issued before 2000 because they either hardly included any language about teaching writing with technology or have been updated in the 21st century. For example, the CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing was first published in 1982 then updated in 2015. I selected statements that have been issued or updated in the period of 2000—2017. If a statement has been updated recently, I used the updated version that reflects the more current philosophy and stance of the issuing organization.

Preliminary reading and keyword searching in the statements resulted in identifying and adding synonyms to the original ones in my list.

Table 1. Search Keywords

|

Keywords in RQs |

Keywords searched in Position Statements |

|---|---|

|

Technology |

Digital (WPA OS 3.0) Media: new media, nonprint media, new media texts, multimedia composition (Composing with Nonprint Media) Multimodal: literacies, projects, experiences, work, information, texts, composing (Multimodal Literacies) Electronic: environment and networks (WPA OS 3.0) |

|

Faculty |

Teacher, instructor (Preparing Teachers of College Writing) |

|

Professional development |

Training (Electronic Portfolios) Mentoring (Preparing Teachers of College Writing) |

Applying these criteria, I selected a corpus of the following 11 statements for analysis in this study:

-

CCCC Position Statement on Teaching, Learning, and Assessing Writing in Digital Environments (2004)

-

CCCC Statement of Preparing Teachers of College Writing (2015)

-

CCCC Position Statement on Principles for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing (2015)

-

CCCC Position Statement: Principles and Practices in Electronic Portfolios (2015)

-

NCTE Resolution on Composing with Nonprint Media (2003)

-

NCTE Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies (2005)

-

NCTE Position Statement: Principles of Professional Development (2006)

-

NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment (2013)

-

NCTE Guideline: Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing (2016)

-

The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing (2011)

-

The WPA Outcomes Statement 3.0 (2014)

Reaching the data appraisal stage (Bowen), I was hesitant to include NCTE statements addressing English Language Arts (ELA) teaching in the study since, at the surface, they seem to be irrelevant to the college composition context. Upon reading those statements more carefully, I grew confident to include them for several reasons:

-

Members of both organizations practice writing instruction, “an activity shared by K-16 teachers” (O’Neill et al. 520).

-

Digital technologies have impacted both the ELA and college composition classrooms almost equally. As stated earlier, scholars across Writing Studies and Education have expressed similar concerns about teacher preparedness to use technology in teaching.

-

The opening section in almost all statements state that the authors had drawn heavily from shared values and from research on writing in “the fields of English Language Arts and Composition and Rhetoric and from existing statements developed by the field’s major organizations” (CCCC Postsecondary Teaching of Writing).

Data Coding

I started a qualitative codebook, “a table that contains a list of predetermined codes” (Creswell and Creswell 196), with a list of predetermined codes extracted from my research questions: ‘expectations about teaching writing with technology’ and ‘professional development’. I simultaneously read the statements, coded segments of the data under the two main categories, and took copious research memos that helped me to capture all my thoughts and contemplations as I was sorting through the data and pondering themes and interpretations.

The inductive analysis of the corpus of statements, meant to produce “patterns, categories, and themes from the bottom up” (Creswell and Creswell 181), had two outcomes. The first was determining the unit of analysis for the complete data set. I chose clauses, or “the smallest unit of language that makes a claim ... about an entity in the world” (Geisler 32). Geisler suggests using clauses as the unit of analysis when the interest of the research “is related to the claims” made about a certain phenomenon or idea, thus its match to the context of this study. The second outcome was revising the original codebook by adding main and sub categories that emerged from the initial reading and coding of data. All categories were operationally defined as demonstrated in Table 2 to facilitate the deductive analysis of data.

Table 2. Operational Definitions of Themes

|

Themes |

Definition |

|---|---|

|

Expectations about teaching writing with technology from teachers |

|

|

Conceptual expectations |

Clauses that clearly describe the knowledge a writing teacher should have in order to effectively teach with technology |

|

Pedagogical expectations |

Clauses that explicitly describe the instructional practices a writing teacher should perform in order to help students become proficient with the tools of technology |

|

Technological expectations |

Clauses that describe a teacher’s skills or behaviors pertaining to using technology (hardware or software) in teaching writing |

|

Professional development |

|

|

Goals |

Clauses that explicitly describe the desired outcomes on the knowledge and pedagogy levels of a professional development program/event on teaching writing (with or without technology) |

|

Content |

Clauses that clearly describe the activities included in a professional development program/event to increase teacher knowledge and improve pedagogical practices |

|

Form |

Clauses that clearly describe the forms/formats of a professional development program/event to increase teacher knowledge and improve pedagogical practices |

I randomly selected two statements (CCCC Teaching, Learning, and Assessing, and CCCC Principles for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing), representing 10% of the data, and shared them and the codebook with a fellow researcher for inter-coder reliability calculation (Creswell and Creswell). After two rounds of independent coding and discussions, we reached r=0.86, a considerably high reliability.

Deductive analysis, or “thorough examination” (Bowen, 32), followed and I used the categories created to examine the data more deeply in search for support for them and/or to refine them. I continued to take research memos to ensure that I was strictly following the definitions of themes, an imperative strategy to establish the reliability of the study (Creswell and Creswell).

What is in the Statements?

The deductive analysis of the 11 selected statements to answer the two research questions posited in this study resulted in determining three levels of technology-related expectations of writing faculty and mapping out the fundamental characteristics of an effective TPD program that would train writing faculty to meet these expectations.

Technology-Related Expectations from Writing Faculty

My first research question is what are the teaching with technology-related expectations from college writing faculty as stipulated in 11 CCCC, NCTE, and CWPA position statements? The analysis reveals that the three professional organizations have collectively created a tapestry of expectations for writing faculty in the area of teaching with digital technologies: conceptual, pedagogical, and technical expectations. I need to stress at the outset of this section that in my scholarship and teaching, I avoid and challenge the imposed binary of theoretical and pedagogical knowledge in the writing classroom because all pedagogy is ideally grounded and framed in the field’s theories and epistemology. The separation of the two areas here is deliberate but loose: deliberate to allow for intricate and nuanced understanding of the theoretical knowledge teachers need before they translate that knowledge into pedagogical practices, and loose because the two areas keep overlapping and intersecting as one should expect them to do. For the sake of analysis in this section, I’m separating the three levels of expectations before I bring them back together in a conversation afterwards.

Conceptual Expectations

The authors of multiple statements have emphasized that the conceptual and theoretical knowledge is requisite and foundational for the pedagogical and technical skills and behaviors. This conceptual knowledge starts with “[t]heory about and history of modalities, and the affordances they offer for meaning making” (Professional Knowledge), which echoes and extends Doug Hesse’s hope for writing teachers to “know the field’s history, research, practices, and contestations” (qtd. in Murphy 81). Studying the theories that have shaped the field of computers and writing and that inform sound pedagogies means that the instructor is not only aware of “the ways digital environments have added new modalities while constantly creating new publics, audiences, purposes, and invitations to compose” (Professional Knowledge), but they can also “introduce students to the epistemic ... characteristics of information technology” (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing). Equally important is instructor awareness of the “range of new genres that have emerged on the Internet” and the “[w]ays to access, evaluate, use, and cite information found on the Internet” (Professional Knowledge).

Equipped with conceptual knowledge, teachers are able to connect it to the “overall literacy goals of the curriculum” (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing) while preparing students for the future when “they are likely to encounter new technologies and new or evolving genres throughout their writing lives” (Postsecondary Teaching of Writing). The conceptual knowledge appears to be fundamental for teachers to prepare students to “learn about the values associated with different technologies that can be used for ... composition” (Postsecondary Teaching of Writing). I’ll add that students can potentially transfer that learning beyond the FYW class where they were first introduced to these technologies.

Another important layer of conceptual knowledge is assessment of new genres and digital writing products and processes. While the Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies establishes the necessity of teaching “skills, approaches and attitudes towards media literacy, visual and aural rhetorics, and critical literacy,” it simultaneously acknowledges that “[t]he difficulty of grading the [multimodal] work using traditional methods may prevent some teachers from attempting this kind of work.” Responses to Anderson et al.’s survey study substantiated the difficulty of assessing multimodal work as majority of respondents reported that they were left to their own devices when it came to assessment of multimodal composing projects, seeking help from websites, research, friends, and colleagues from other institutions (70). Participants also expressed frustration over a number of conceptual and pedagogical problems pertaining to assessing multimodal work, such as “maintaining fairness” and “lacking clearly articulated criteria and standardized grading practices” (72), thus pointing to the importance of conceptual knowledge for writing teachers interested in or tasked with teaching and assessing digital texts.

These conceptual expectations translate into pedagogical ones as writing teachers are expected to provide rigorous and informed instruction as they continue to provide classroom opportunities for composing with digital technologies.

Pedagogical Expectations

The pedagogical expectations from writing faculty mainly include instruction and discussions that prepare students for analysis of electronic texts and hands-on digital composing and production opportunities. These pedagogies will help students “[d]evelop facility in responding to a variety of situations and contexts calling for purposeful shifts in voice, tone, level of formality, design, medium,” a significant learning outcome (WPA OS 3.0). The ultimate goal is for students to be able to transfer the skills they develop through using digital technologies to solve problems in the “academic, professional, civic, and/or personal realms of their lives” (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing). In my recent study, I found that writing teachers with a critical approach to using new media technologies “foregrounded the role of instruction and communicating their choices and decisions to students” and argued that such explicit instruction “is likely to contribute to student understanding more about technology” (Mina 12). My argument accentuates the crucial role of deliberate instruction that would ultimately facilitate the transfer of their learning about and with technology beyond their time in the writing classroom.

Additionally, writing teachers are expected to “include ample in-class and out-of-class opportunities for writing, including writing in digital spaces” (Professional Knowledge). As teachers design and plan their instruction, they should ensure that “hands-on use of technologies” is an integral part in their plans (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing). The Framework for Success stipulates that these opportunities help students develop cognitive abilities (e.g., critical thinking) and perform certain tasks (e.g., revise and edit their and their peers’ work). Combined, these statements seem to expect teachers to use knowledge of digital technologies, conventions of digital composing, and an awareness of digital and visual design and rhetoric to prepare students who are “thoughtful, effective users of electronic technologies” (Framework for Success, 10), demonstrating the complexity and intersection of the conceptual and pedagogical expectations from writing faculty, particularly in teaching multimodal composition and e-portfolios.

A number of statements emphasize that teachers should introduce students to a wide range of technologies and tools that they may use at the various stages of the writing process, especially while composing multimodal work. These projects present opportunities for students to explore the use of web and mobile apps to “create podcasts, videos, or other multimedia work,” and teachers should use “multiple strategies” to help students with problems while composing their texts, such as the “incorporation of images and other visuals” (Professional Knowledge). Ideally, the help teachers are expected to extend should be technical and rhetorical, meaning that they are expected to understand the rhetoric and parameters of incorporating visuals in a text so that these visuals function in more than an aesthetic role.

Throughout the multimodal composing processes, instruction should be always paired with and grounded in the foundational theoretical principles of rhetoric and composition in order for students to “match the capacities of different environments ... to varying rhetorical situations” and to be able to “[a]dapt composing processes for a variety of technologies and modalities” (WPA OS 3.0). Once students have produced drafts of text in different modalities and on various platforms, the teacher is ready to provide feedback using the available and suitable digital technologies, such as “screencasting and annotating, embedded text and voice comments, and learning management systems” (Professional Knowledge).

In the context of e-portfolios, writing faculty are expected to discuss a wide range of topics with students at the different stages of assembling their e-portfolios. A teacher should engage students in critical discussions of a) selecting the digital platform that will host their portfolios, b) “the ethical use of digital sources ... and protocols for obtaining permission and documenting digital sources,” and c) access issues and “the benefits and disadvantages of students allowing public access to their documents” (Electronic Portfolios). The teacher should then offer “direct instruction in ethical, critical, and legal considerations” of digital and multimodal practices (Multimodal Literacies) so that students can make the right decision for their e-portfolios.

These findings illustrate the inevitable entanglement of the conceptual and pedagogical knowledge expectations, pointing to the inadequacy of separating technology from the theories underpinning its use or from the teaching context in which it will be integrated.

Technological Expectations

In addition to these conceptual and pedagogical expectations, the statements indicate that writing teachers need to develop a set of technological knowledge (e.g., knowledge of available platforms and apps) and technical skills (e.g., ability to use and troubleshoot software). In addition to the knowledge needed for multimodal projects discussed in the previous section, the authors of the NCTE Statement on the Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing provide a list of what constitutes this technological knowledge: technologies that aid in the brainstorming stage, such as “drawing tools and voice-to-text translators,” technologies used during the composing stage, and “open-source platforms that students use” for various purposes. The writing teacher is also expected to know about “[o]peration of hardware and software” as well as troubleshooting and software update resources.

Looking at these findings as pieces of a large puzzle, it is obvious that faculty are expected to have a certain degree of all three levels of knowledge-conceptual, pedagogical, and technological-in order to be able to comfortably and effectively teach writing with digital technologies. These findings mean that the complex set of expectations is neatly contextualized in teaching and organically connected to student learning. Meanwhile, this finding leads us to consider faculty lacking in one or more of these areas while tasked to teach with technology and to achieve technology-related outcomes. The answer is simple: offer ongoing TPD programs that provide faculty with the conceptual, pedagogical, and technological knowledge and skills expected from them before and during teaching with technology. The following section discusses such programs.

Characteristics of Professional Development Programs

Moving to the second research question in this study (What are the characteristics of technology professional development programs, as identified in these statements, that train teachers to meet these expectations?), I found that multiple statements discuss PD of writing faculty, with fewer focusing on TPD opportunities. I’d like to point out that while this is not a favorable finding, it does not necessarily mean that our field, represented by the three leading organizations, does not care about technology training of writing faculty. I’d reiterate what I stated earlier that the varied exigences of producing these position statements have dictated certain purposes for these statements, and that technology training was neither an explicit nor an implicit purpose of any of the statements analyzed in this study.

Some statements address the meaning of and need for PD of writing faculty in broad strokes, whereas others provide more pragmatic details about the goals, content, and form of these PD programs.

Defining Professional Development

The CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing defines PD as “formal mentoring by more experienced or expert colleagues” that aims to “support postsecondary instructors throughout their careers” and is characterized by “sustained activities ... and by community-based learning.” This definition points to two important features of a good PD program: community and sustainability. PD as mentoring implies that experienced and novice faculty form learning communities (Kanaya, Light, and Culp) in which they “discuss the real-life obstacles they may face in their classes” (Mina 14). Lawless and Pellegrino found that mentoring in technology training programs provides more personalized consultation, which is likely to help teachers feel more comfortable using the content of the program to integrate technology in their classes. This mentoring cannot take place in the one-shot technology-based workshop model that many scholars have repeatedly argued against because it’s neither sustainable nor contextualized in the “ongoing pedagogical needs of teachers” (Lawless and Pellegrino 594).

The same CCCC statement also introduces PD as a form of “ongoing formative assessment” of writing teachers that allows for their improvement. Kanaya, Light, and Culp discuss this notion in the context of technology training and note that teachers find PD programs that acknowledge and build on their existing knowledge and can be linked to their individual goals, making the effort more rewarding and enticing for them to integrate technology in their teaching. This conceptualization of PD and linking it to individual goals and improvement may explain how the authors of the CCCC statement expect writing faculty “to stay informed of disciplinary scholarship, to modify their pedagogical practices to mirror shifts in disciplinary scholarship” and to “integrate contemporary composition theory and research into their teaching practices.” These PD needs are more pressing for writing faculty required to teach writing with digital technologies, specifically those who have not studied teaching writing with digital technologies in graduate coursework, have not been to conferences or training programs that develop their teaching with technology conceptual or pedagogical knowledge, or have been out of graduate school for extended periods of time and their knowledge need update. The NCTE Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies explicitly links PD to technology and asserts that unless “traditional teachers” are offered the resources needed, they may not “begin to incorporate new literacies into their classrooms on a continuing basis.” This stipulation suggests that the successful and sustainable incorporation of new literacies and technologies in the writing classroom is conditioned by the availability of both material (e.g., infrastructure and budget) and intellectual (e.g., PD and mentoring) resources for TPD programs for writing faculty.

The CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing furthers the argument by associating the availability of PD programs and “the concerns of postsecondary institutions” of retention and degree completion. Consequently, the statement strongly argues that “investment in the training and professional development of writing instructors is an investment in student learning and success,” which usually translates in student persistence and higher retention rates. As new literacies and digital composing make more appearances in many writing program learning outcomes, providing TPD programs that train teachers in these areas is no longer a luxury or optional; it is a pivotal requirement in order to achieve student success and increase retention, the ultimate goal of writing programs and higher education institutions.

Toward achieving the goal of offering quality PD programs, ideally there should be “direction and clarity regarding what principles should inform the preparation and continued professional development of postsecondary writing instructors” (Preparing Teachers). These principles include setting clear goals, identifying and choosing relevant content, selecting appropriate and sustainable forms, and reviewing and assessing the program for its efficacy. Fortunately, some statements discuss these principles.

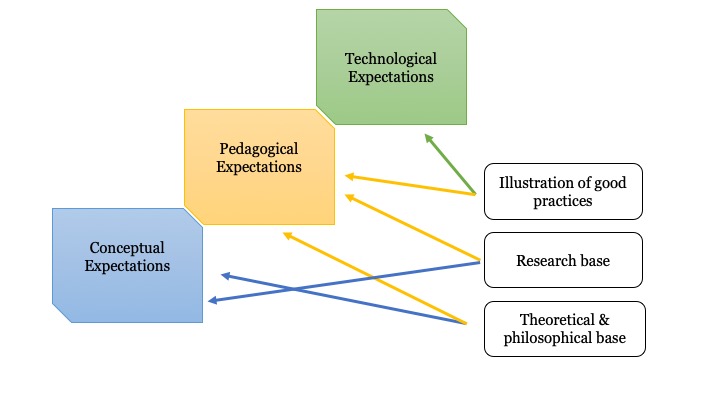

Goals, Content, and Forms of Effective PD Programs

The stated goal of PD programs is “for instructors to learn about and apply shifts in disciplinary scholarship” (Preparing Teachers). This scholarship should ideally include both the theoretical and pedagogical aspects of teaching writing with technology because “sound writing instruction” and pedagogical practices are grounded in “knowledge of theories of writing” (Postsecondary Teaching of Writing). In order to achieve this goal, the NCTE Principles of Professional Development describes a successful and effective PD program as one that “relies on a rich mix of resources, including a theoretical and philosophical base; a research base; and illustrations of good practices.” Applying these parameters to TPD, it is easy to see how they mirror and can help fulfill the three levels of technology-related expectations of writing teachers discussed above and illustrated in Figure 1 below.

Figure 1. The Interplay between Expectations and TPD Content

Building a TPD program that meets these parameters means to “focus on new literacies, multimodal composition, and a broadened concept of literacy” (Composing with Nonprint Media). Establishing this solid conceptual foundation ensures that teachers can adapt and adjust their pedagogical practices to their unique local contexts because they have the knowledge that enables them to make varied and flexible choices. Focusing entirely on pedagogy or technology without packaging it with underlying theories and supporting it with current research is futile because it doesn’t offer a bedrock for teachers to build on for various contexts: student populations, writing courses, and learning outcomes.

PD programs can take “many different forms and employs various modes of engagement” (Professional Development), including “workshops, courses, individual consultations, and Web resources” (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing) housed in the same institution or attending “local, regional, or national Composition and Rhetoric conferences” (Postsecondary Teaching of Writing). Despite the fact that these are reasonable and feasible forms of PD programs, some of them remain available to full-time faculty only who may qualify for “tuition remission for enrollment in graduate-level courses” (Preparing Teachers) or have access to travel fund to attend conferences and institutes, leaving part-time adjuncts without access to any of these possibilities.

So, What Does This All Mean?

The above results demonstrate that the leading organizations in the field have invested large resources to clearly articulate the conceptual, pedagogical, and technological expectations of teaching writing with technology (92 clauses coded), with less emphasis on describing the need for and characteristics of robust TPD programs for in-service writing faculty (39 clauses coded) to be able to meet those expectations. The analysis of this corpus of position statements points to a number of critical issues related to technology professional development of writing faculty: access to TPD opportunities, TPD models, and TPD and student success.

TPD Opportunities: Required vs. Recommended

Although the CCCC Statement of Preparing Teachers of College Writing is remarkably explicit and thorough in articulating the needs of faculty teaching college writing, there is a noticeable discrepancy in the requirements of preparing graduate teaching assistants and new and continuing faculty on teaching with technology. While taking “graduate-level course work in teaching with technology” was required for the first group, it was only recommended for the latter, which creates a gap between the knowledge and skills each group will bring to their teaching contexts. Admittedly, the statement authors required institutions to provide continuing faculty with financial support to enroll in graduate-level courses in teaching with “digital media” and to participate in “pedagogy workshops.” This is an admirable endorsement of technology training from our flagship organization. The reality on the ground may not always be conducive to implement these recommendations though. For example, enrolling in graduate-level courses may not always be feasible for full-time and tenure-line faculty loaded with research, teaching, service, and sometimes administrative responsibilities, and many faculty may consider this opportunity “a course overload” as Michael Murphy suggests (83). The statement also appears to overlook the reality of labor and employment conditions of contingent faculty, who don’t typically have access to similar financial resources or opportunities in most universities, which makes this stipulation void for majority of faculty teaching FYW courses. Given the context of this statement, it is not surprising that there is no extensive or focused discussion of offering these pedagogy workshops at the institution where these teachers work, making TPD opportunities more accessible and equitable to all faculty. Other statements in the corpus analyzed in this study overlooked these details as well. Given that contingent faculty’s unequal access to technology-and, I add, to technology training resources-surfaced as a main concern among writing teachers and scholars in response to the WPA OS 3.0 (Dryer et al.), I argue that these access problems jeopardize critical and successful integration of technology in the writing classroom.

Interestingly, the same CCCC Statement expects writing teachers to be active and agentive in seeking PD opportunities. Teachers are expected to “labor diligently to stay informed of disciplinary scholarship, to modify their pedagogical practices to mirror shifts in disciplinary scholarship.” By making teachers responsible for their own PD, the statement underscores the need for ongoing robust PD programs that incorporate scholarship and pedagogy and their role in improving faculty’s pedagogical practices, whereas it implies that PD is a personal choice of the individual teacher rather than an institutional or programmatic commitment to the professional development of writing faculty. I agree that faculty should seek and pursue PD opportunities available to them, but placing the responsibility squarely on the faculty alone is neither fair nor practical because of the varied factors that may affect their choice: teaching loads, job security, access to resources, and availability and affordability of local PD programs, to name a few.

These findings point to an unequal access problem: graduate students in large research institutions have access to graduate-level courses, teaching, mentoring, and research opportunities to learn about and be qualified to meet those robust expectations of teaching with technology (Anderson et al.; Blair; Hauman et al.; Reid et al.). Meanwhile, continuing faculty, particularly contingent faculty who are largely responsible for teaching FYW courses, may not have equal access to similar opportunities despite the professional organizations’ recommendations-recommendations which may not be suitable for local contexts of small institutions or varied work conditions across institutional types.

TPD Models: Separative vs. Integrative

The reference to teaching with technology appears once in the CCCC Statement of Preparing Teachers of College Writing in the form of “technical knowledge” writing teachers need, demonstrating a negligible interest in such an important aspect of teaching writing in the 21st century. Isolating the teaching of writing with technology from its theoretical, rhetorical, and pedagogical framework represents an instrumental or functional approach to using technology (Mina). In my recent work, I found that teachers’ approaches to using new media technologies in teaching FYW were overwhelmingly instrumental, noting that these approaches may be a result of training programs aligned with the instrumental rather than the critical approach. That is, when TPD programs are technocentric or concerned with teachers’ technical skills in a separative model, teachers perceive technology as an add-on element in their teaching, without considering its underlying theories. In other words, teachers can’t become critical users of technology in their own classes, which casts much doubt on how successful they can be in preparing students who can “[c]reate, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia text” (Framework for 21st Century Curriculum).

Mishra and Koehler challenge the view of technology as independent from content and pedagogy. They claim that separation model limits some teachers’ perception of technology as “relatively trivial to acquire and implement” (1025). Therefore, they argue that content, pedagogy, and technology should be presented in an integrative model that highlights the complexity of their relationship. They also note that teachers need to think critically of their use of technology and should equally develop their knowledge of the pedagogy that incorporates that technology, and the content they will teach using this pedagogy. Lawless and Pellegrino add that teachers need time to reflect on how the PD content has affected their learning and pedagogy, implying that the training faculty undergo shouldn’t be limited to technical skills or practice. Expanding their theoretical and pedagogical knowledge that gives faculty a reference point to reflect on their teaching situation and to make informed decisions on how to integrate their new knowledge and skills to improve student learning.

Schrum brings in another perspective that underscores the role of an integrative TPD model in remedying faculty reluctance to teaching with technology. She asserts that while faculty may be reluctant to use technology because of their lack of familiarity with it, they may be willing to engage in TPD events if provided with a clear rationale of why they need to change their instruction models or pedagogies. Kanaya, Light, and Culp further explain this argument and state that teachers are more open to participate in and learning from PD if these opportunities allow them to connect the new knowledge to their existing knowledge. They also note that good TPD programs should do much more than enhance teachers’ technical skills; student learning needs to be the ultimate goal and focus.

A good example to close the discussion about the separative vs. integrative model comes from how multimodal work was presented in some position statements. The NCTE Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies tends to concentrate almost exclusively on student “skills” required to complete such work. This oversimplification of multimodal work and confining it in the technical skills zone can also be found in a declaration in the same statement that “[y]oung children practice multimodal literacies naturally and spontaneously.” Equating “digital self-sponsored” practices (Rosinski 249) that students engage in outside the classroom with multimodal literacies that involve critical and rhetorical awareness of media affordances and limitations is problematic. Rather than reducing multimodal composing and digital literacy to technical skills, these writing practices should be used as a springboard for students to continue to explore all various “modes of expression,” and for the teacher to develop “an assessment process” to effectively confidently “evaluate electronic texts” (Professional Knowledge).

This complexity of multimodal work requires substantial knowledge of the theories underpinning multimodal and digital composing in the classroom and requires rigorous conceptual learning about assessing digital work. Charles Moran and Anne Herrington extensively emphasize the complexity of assessing multimodal work and warn that lacking this knowledge may deter teachers from engaging in that work or assigning it in their classes. They particularly warned that when teachers who neither received sufficient training on teaching with technology nor have much interest in digital technologies are asked to teach a technology-rich curriculum, performing that task “proves a challenge.” Moran and Herrington’s comments point to the pressing need to train writing faculty on different aspects of teaching with digital technologies through ongoing TPD programs in order to manage that “challenge”.

While this example highlights the significance of teacher knowledge and, consequently, teacher training and PD that harnesses that conceptual knowledge, it accentuates the organic connection between teacher conceptual, pedagogical, and technological knowledge to teach with technology and student learning.

Student Learning and Success

The CCCC Statement of Preparing Teachers of College Writing connects the “technical knowledge” required for writing teachers to student success in the 21st century which is defined in another statement as students having “proficiency and fluency with the tools of technology” and their ability to “create, critique, analyze, and evaluate multimedia texts” (Multimodal Literacies). In their discussion of the content of PD with regard to technology, Lawless and Pellegrino emphasize that the content should support “student development of conceptual understanding” of technology (581), and that if integrated thoughtfully, the use of technology can result in favorable learning outcomes. In order for students to develop these abilities, I suggest elsewhere that in using digital technologies in the writing classroom, teachers “are encouraged to communicate goals to students in order to secure their full engagement in new media-rich projects” (Mina 12). I argue that active instruction about these goals will facilitate student conceptualization of the technologies they use, which in turn help them develop technological literacy skills.

This discussion emphasizes that student learning must be the ultimate goal and focus of an effective TPD program, thus positioning the goal for “instructors to learn about and apply shifts in disciplinary scholarship” (Preparing Teachers) as an immediate, short-term goal and enhanced student learning as the long-term one. Achieving both goals necessitates investing in designing and offering quality TPD programs that take into consideration the local institutional needs, programmatic goals, teacher prior knowledge and individual goals, and student learning outcomes and the interplay of all these variables to achieve better student learning in the 21st century.

Bringing it all Together

Findings of this study highlight the need for robust, ongoing TPD programs in post-secondary institutions. Since incorporating and using digital technologies should be driven by “university, department, and course learning goals or outcomes” (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing), designing TPD programs should be the responsibility of department chairs and writing program administrators (WPAs). Particularly, WPAs are responsible for securing faculty access to “diverse forms of technical and pedagogical professional development before and while they teach in digital environments” (Teaching, Learning, and Assessing), and they should collaborate with various units on campus to secure access to physical (infrastructure and hardware) and symbolic (software, training, and technical support) resources. Together, these training opportunities will facilitate meeting the conceptual, pedagogical, and technical expectations of teaching with technology.

The institutional responsibility to provide writing faculty with these opportunities is not only professional but, I argue, ethical as well. The authors of the NCTE Statement on Multimodal Literacies emphasize in more than one place the significance of closing the digital divide between students who have easy access to digital technologies outside school and those who don’t. However, narrowing the divide between teachers who know how to teach with these digital technologies and those who don’t is equally significant. Advocating for developing the infrastructure at school to secure equal student access to technologies (Multimodal Literacies) should be parallel with providing teachers with the conceptual, pedagogical, and technical training required for them for optimum utilization of these infrastructure and resources. Investing in one without investing in the other raises questions about higher education’s commitment to social justice and equity issues because the CCCC Statement on Working Conditions for Non-Tenure-Track Writing Faculty recommends “equity for NTT writing faculty to issues associated with ... opportunities for professional development.” Continuing to place PD of writing faculty, especially on teaching with digital technologies, at the periphery of our attention as seen in the results of this study undermines many of the efforts put forward by these organizations for more equity between college writing teachers.

It may be time for one or more of the leading professional organizations to issue a comprehensive position statement on training writing faculty on teaching with digital technologies. I’d recommend that statement include clear articulation of the significance of offering robust technology professional development programs, the characteristics of these programs, and their role in achieving student success.

Where to Go from Here

While findings of this study have answered the research questions posited at the outset of this project, they raise more topics that I hope will stimulate future research in this significant and quite neglected area:

-

Faculty, especially contingent faculty, access to TPD programs

-

Whether these programs are designed on the parameters identified in the position statements of the field

-

The forms, content, and assessment of these programs

-

The potential relationship between training writing faculty on effective teaching with technology and student transfer of writing knowledge and practices beyond their writing classes

Additionally, there is an equally important direction for future scholarship that examines WPAs’ awareness of the expectations of teaching with technology and their own responsibility for creating and coordinating the TPD opportunities that train faculty in their programs and departments. This study can offer a vantage point for other scholars to pursue these promising and needed lines of research.

Works Cited

About CCCC. Conference on College Composition and Communication. https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc-about/.

Anderson, Daniel, et al. Integrating Multimodality into Composition Curricula: Survey Methodology and Results from a CCCC Research Grant. Composition Studies, vol. 34, no. 2, 2006, pp. 59-84.

Blackmon, Samantha, and Shirley K. Rose. Plug and Play: Technology and Mentoring Teachers of Writing. Don't Call It That: The Composition Practicum, edited by Sidney I. Dobrin, National Council of Teachers of English, 2005, pp. 98-112.

Blair, Kristine. Preparing 21st-Century Faculty to Engage 21st- Century Learners: The Incentives and Rewards for Online Pedagogies. Higher Education, Emerging Technologies, and Community Partnerships: Concepts, Models and Practices, edited by Melody A. Bowdon and Russell G. Carpenter, IGI Global, 2011, pp. 141-161.

Bowen, Glenn A. Document Analysis as a Qualitative Research Method. Qualitative Research Journal, vol. 9, no. 2, 2009, pp. 27-40.

CCCC Position Statement on Teaching, Learning, and Assessing Writing in Digital Environments. College Composition and Communication, vol. 55, no. 4, 2004, pp. 785-790.

CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2015. http://www.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/statementonprep.

CCCC Statement on Working Conditions for Non-Tenure-Track Writing Faculty. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2016. http://www.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/working-conditions-ntt.

Condon, William, et al. Faculty Development and Student Learning: Assessing the Connections. Indiana University Press, 2016.

Creswell, John W., and J. David Creswell. Research Design: Qualitative, Quantitative, and Mixed Methods Approaches. SAGE, 2018.

Dryer, Dylan B., et al. Revising FYC Outcomes for a Multimodal, Digitally Composed World: The WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (Version 3.0). WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 38, no. 1, 2014, pp. 129-143.

Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. Council of Writing Program Administrators, National Council of Teachers of English, and the National Writing Project, 2011. http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/collwritingframework.

Francis, John Bruce. How Do We Get There from Here?: Program Design for Faculty Development. The Journal of Higher Education, vol. 46, no. 6, 1975, pp. 719-732.

Geisler, Cheryl. Analyzing Streams of Language: Twelve Steps to the Systematic Coding of Text, Talk, and Other Verbal Data. Pearson Longman, 2004.

Hauman, Kerri, et al. Writing Teachers for Twenty-First-Century Writers: A Gap in Graduate Education. Pedagogy, vol. 15, no. 1, 2015, pp. 45-57.

--- The Language of Technology in Professional Documents and Local Contexts: Cultivating Technologically Responsive Positions, Practices, and Persons. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2017.

Kanaya, Tomoe, et al. Factors Influencing Outcomes from a Technology-Focused Professional Development Program. Journal of Research on Technology in Education, vol. 37, no. 3, 2005, pp. 313-329.

Lawless, Kimberly A., and James W. Pellegrino. Professional Development in Integrating Technology into Teaching and Learning: Knowns, Unknowns, and Ways to Pursue Better Questions and Answers. Review of Educational Research, vol. 77, no. 4, 2007, pp. 575-614.

Mina, Lilian W. Analyzing and Theorizing Teachers’ Approaches to Using New Media Technologies. Computers & Composition, vol. 52, 2019, pp. 1-16.

Mishra, Punya, and Matthew J. Koehler. Technological Pedagogical Content Knowledge: A Framework for Teacher Knowledge. Teachers College Record, vol. 18, no. 6, 2006, pp. 1017-1054.

Moran, Charles, and Anne Herrington. Seeking Guidance for Assessing Digital Compositions/Composing. Digital Writing Assessment and Evaluation, edited by Heidi McKee and Danielle Nicole DeVoss, Computers and Composition Digital Press/Utah State University Press, 2013, http://ccdigitalpress.org/dwae/03_moran.html.

Murphy, Michael. Head to Head with Edx?: Toward a New Rhetoric for Academic Labor. Contingency, Exploitation, and Solidarity: Labor and Action in English Composition, edited by Seth Kahn et al., The WAC Clearinghouse and University Press of Colorado, 2017, pp. 71-89.

Myatt, Alice Johnston, and Ellen Shelton. Applications of the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing at the University of Mississippi: Shaping the Praxis of Writing Instructors. The Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing: Scholarship and Application, edited by Nicholas N. Behm et al., Parlor Press, 2017, pp. 187-203.

NCTE Framework for 21st Century Curriculum and Assessment. National Council of Teachers of English, 2013. http://www2.ncte.org/statement/21stcentframework/.

O'Neill, Peggy, et al. Creating the Framework for Success in Postsecondary Writing. College English, vol. 74, no. 6, 2012, pp. 520-524.

Position Statement on Multimodal Literacies. National Council of Teachers of English, 2005. http://www2.ncte.org/statement/multimodalliteracies/.

Principles and Practices in Electronic Portfolios. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2015. http://www2.ncte.org/statement/electronicportfolios/.

Principles of Professional Development. National Council of Teachers of English, 2006. http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/profdevelopment.

Professional Knowledge for the Teaching of Writing. National Council of Teachers of English, 2016. http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/teaching-writing.

Reid, E. Shelley et al. The Effects of Writing Pedagogy Education on Graduate Teaching Assistants’ Approaches to Teaching Composition. Writing Program Administration, vol. 36, no. 1, 2012, pp. 32-73.

Resolution on Composing with Nonprint Media. National Council of Teachers of English, 2003. http://www2.ncte.org/statement/composewithnonprint/.

Rosinski, Paula. Students’ Perspective of the Transfer of Rhetorical Knowledge between Digital Self-Sponsored Writing and Academic Writing: The Importance of Authentic Contexts and Reflections. Critical Transitions: Writing and Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, The WAC Clearinghouse/University Press of Colorado, 2017, pp. 247-271.

Schrum, Lynne. Technology Professional Development for Teachers. Educational Technology Research and Development, vol. 47, no. 4, 1999, pp. 83-90.

Statement of Principles and Standards for the Postsecondary Teaching of Writing. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2015. http://www2.ncte.org/statement/postsecondarywriting/.

Takayoshi, Pamela and Brian Huot. Introduction. Teaching Writing with Computers: An Introduction, edited by Pamela Takayoshi and Brian Huot, Houghton Mifflin Company, 2003, pp. 1-13

The NCTE Definition of 21st Century Literacies. The National Council of Teachers of English http://www.ncte.org/positions/statements/21stcentdefinition.

WPA Outcomes Statement for First-Year Composition (V3.0). Writing Program Administration, vol. 38, no. 1, 2014, pp. 144-148.

Technology Professional Development from Composition Forum 43 (Spring 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/43/professional-development.php

© Copyright 2020 Lilian W. Mina.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 43 table of contents.