Composition Forum 48, Spring 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/48/

Mapping Long-Term Writing Experiences: Operationalizing the Writing Development Model for the Study of Persons, Processes, Contexts, and Time

Abstract: Drawing upon nine years of qualitative data, including a collection of writing samples and yearly interviews, this study seeks to articulate a model of long-term writing development that can be adapted for a wide range of research and teaching purposes. The model is adapted from Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s Bioecological model of human development and draws upon key works by writing transfer scholars, longitudinal researchers, and the work in lifespan development. The model identifies the critical interplay of ecologies of writing specifically through the intersection of Person characteristics (e.g., Identities, Dispositions, and Resources) with Key Events over Time, nested in particular writing Contexts. We specifically focus on the way that various Person characteristics (including sociocultural, sociolinguistic, and socioeconomic), drastically shape writing development over Time, particularly as they are mediated by the Salience of the specific Writing Event and a writer’s metacognitive awareness. Through case studies, we trace two writers’ long-term development across nine years, spanning their undergraduate degrees, internship and workplace contexts, and for one writer, experiences in medical school contexts. With a model that can be applied to a variety of research and teaching contexts to better understand learners’ writing development, we argue that Person characteristics—mediated by Salience and Metacognition and working together with Key Events, Contexts, and Time—substantially shape long-term outcomes for writing and learning. Through this robust model, we offer methodological and pedagogical implications.

I. Introduction

In a recent email exchange between several college administrators discussing a student’s need for additional writing support at our institution, one administrator wrote, “She really wants to succeed but I think she came to school with a pretty empty toolbox.” This statement reflects a recognition of the interplay between characteristics that students bring with them into learning settings and their long-term development as writers. Even though the student is a junior English major, her “empty toolbox” still is influencing her success as a writer. Questions and discussions about how to support students with different “toolboxes” are quite common across institutions of higher education, especially as institutions are faced with increasingly diverse student populations. Researchers, likewise, committed to exploring questions of what helps drive, support, or prevent long-term writing development. Some of these developmental factors researchers have considered include the role of writing transfer, or the ability of students to engage and adapt prior knowledge (Wardle, Mutt Genres; Yancey et al.; Nowaceck) and increased attention to long-term aspects of learning to write (Bazerman et al.). Most of these studies are explorations with a small number of student writers, focusing on key features such as the influence of genre knowledge (Reiff and Bawarshi; Rounsaville et al.; Rounsaville; Adler-Kassner et al.), metacognition (Anson), threshold concepts (Adler-Kassner and Wardle), or the improvement of writing over time (Oppenheimer, et al.). Additionally, a regular stream of longitudinal studies, such as Donahue and Foster-Johnson, Beaufort, Sternglass, and Herrington and Curtis, have offered more comprehensive understandings of the nuanced aspects of the interaction of writers with their Contexts, most often in academic and workplace settings. Thus, a growing discussion is taking place about the complexity of writers’ development and the factors that shape it (Donahue and Foster-Johnson; Elon Statement; Anson and Moore).

Despite these many studies, however, more comprehensive modeling and integration of the different factors that shape long-term learning to write, particularly in college settings, is still underdeveloped. Arguing for this developmental perspective, Bazerman et. al (Taking the Long View) have articulated that “lifespan research” may be useful to “create an integrated picture of writing development as a multidimensional process that continues across the lifespan” (352). This article seeks to respond to Bazerman et al.’s call and offer a comprehensive model for writing development through an ecological exploration and integration of Personal charcteristics, Key Events, Context, and Time.

Drawing upon nine years of qualitative data, including a collection of writing samples and yearly interviews and the “lifespan” of two complete educational histories of writers, we offer the Writing Development Model, adapted from Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s Bioecological model of human development and drawing upon other key theories within writing studies. We use case studies from two writers to demonstrate the ways in which Person characteristics—Identities, Resources, and Dispositions—help shape writing development in specific Contexts over Time. With fine-grained anaylsis of empirical data, we argue that Person characteristics not only substantially shape writing development across Time with developmental factors of Salience and Metacognition, but also work together with Key Events, Contexts, and Time to influence writers’ long-term outcomes for writing and learning. Thus, this article offers a data-driven model with explanatory power for both research and teaching contexts to help us better understand and support learners’ long-term writing development, as well as specific nuance about the critical interactions between Persons, Contexts, and Key Events over Time that drive said development.

II. Literature Review

Understanding Writing Development

The publication of Bazerman et. al’s The Lifespan Development of Writing offers a contribution in considering long-term writerly development. Drawing on different disciplinary expertise and a large body of work, the authors propose eight principles to guide further inquiry into lifespan development of writing:

-

Writing can develop across the lifespan as part of changing contexts.

-

Writing development is complex because writing is complex.

-

Writing development is variable; there is no single path and no single endpoint.

-

Writers develop in relation to the changing social needs, opportunities, resources, and technologies of their time and places.

-

The development of writing depends on the development, redirection, and specialized reconfiguring of general functions, processes, and tools.

-

Writing and other forms of development have reciprocal and mutually supporting relationships.

-

To understand how writing develops across the lifespan, educators need to recognize the different ways language resources can be used to present meaning in the written text.

-

Curriculum plays a significant formative role in writing development. (354-357)

In reviewing the eight principles, a heavy emphasis is placed on Time (principle 1, 3), Context (principle 1, 3, 4 ), and on the specific nature of writing and language (2, 5, 6, 7). However, little attention in these principles is offered to writer’s “toolboxes,” namely writer’s Dispositions, Identities, or Resources, which we argue are as important as other contextual factors.

Paul Prior notes that additional research is needed to gain understandings about the complex lifespan writing development; he challenges the specificity and actionability of the eight principles above. Additionally, Prior points out the lack of epistemological, theoretical, and disciplinary frameworks that undergird these principles, a concern shared by the present authors, and something this work seeks to address. He proposes that research on lifespan writing development needs to investigate embodied, mediated, dialogic semiotic practice as its unit of analysis and cover different domains of writers’ lives (Prior, p. 215). We take up Prior’s call: the need for theoretically sound frameworks and embodied practices that cover different domains of writers’ lives in an ecological framework.

Another major issue in Bazerman et. al.’s work is the lack of emphasis on the power and influence of “Person” characteristics—an individual learner’s set of experiences, knowledge, dispositions, and identities, shaped by socioeconomic, sociocultural, and sociolinguistic factors. The importance of Person characteristics have been documented in previous longitudinal studies of writers (College Writing and Beyond; Eodice et al.; Sternglass; Herrington and Curtis). A key aspect of these long-term studies is the interrelationship of learners’ Contexts and previous experiences with specific writing experiences. Eodice et al. explored the responses of 707 seniors at three diverse institutions to understand what “meaningful writing” was for participants noting that projects need to cultivate personal connections (130). Herrington and Curtis explored the growing writerly identities of four students across nine years of college writing experiences. Their primary focus is on the relationship between a writer’s emotional connections and how student writers navigated these identity-based meanings in various writing Contexts. Sternglass and Roozen each suggest we need to understand the range of experiences and identities outside of the classroom that are central to understanding writers’ long-term development. These studies suggest that Person characteristics to a learner are as critical as any other feature of writing development and we argue, should be clearly accounted for in any developmental models or principles.

Modeling Writing Development

How might we account for the multitude of factors that shape development so that these “Person” characteristics are not left out? Without robust models helping frame and shape our research, we will be forced to consider the long-term writing development of writers in a piecemeal fashion, or, as in the case of Bazerman et al., leave out critical Person aspects. While models have been used in studying portions of writing development, particularly writing transfer, none of them are developmental in nature or consider Time as a critical factor. Several models exploring the relationships between writers, texts, and rhetorical situations have been used, such as Beaufort’s discourse community model (Operationalizing the Concept; College Writing and Beyond), Engeström’s activity theory model, and Wenger’s community of practice model. While Beaufort’s model is specific to writing and describes discourse communities in an individual’s writing process, Engeström’s and Wenger’s are not specific to writing, but have been adapted by scholars studying writing (Russell Rethinking Genre; Activity theory). Other models help us understand the nature of writing knowledge, including threshold concepts (Adler-Kassner and Wardle) and metacognition (Gorzelsky et al.).

One potentially rich model that directly addresses the interaction of Persons, Contexts, and Time is the Bioecological Model of Human Development, developed by Bronfenbrenner and Morris. It has most frequently been used to understand sociological factors, such as the development of children and families (Tudge et al.) or the “ecologies” in which humans live and work (Moen et al.). In its most basic form, the model posits that humans develop via “proximal processes” that are shaped by three interrelated factors. That is, for a Person to engage in any development, that process begins with an individual Person (who brings their prior experiences, resources, dispositions, and so forth), who sits in a set of nested Contexts, and who develops through the passage of Key Events in Time. According to Bronfenbrenner and Morris, the “Person” aspects of this model drive development and are the “precursors and producers of later development” (810).

Two previous works, Slomp as well as Driscoll and Wells, have both proposed this model as a useful framework to consider writing transfer, although neither work operationalized it for writing studies or offered an in-depth review of how the model may apply to long-term writing development. Slomp theorized the use of the Bioecological model as a lens to study writing transfer in the Context of writing assessment. Driscoll and Wells used the model to help articulate the importance of dispositional (Person) characteristics from their two longitudinal qualitative studies, both spanning a year’s data collection. We build from these arguments in three directions: first, offering an adapted model to bring it in line with current writing studies scholarship; second, fully operationalizing the model and providing key definitions; and third, providing two student case studies that explore how this model helps understand and account for long-term writing development using a nine-year dataset. Thus, we offer an adapted, operationalized, and applied model employing longitudinal case study research.

The goal of the present study seeks to build upon the work of transfer scholars (Driscoll and Wells; Slomp), longitudinal researchers (College Writing and Beyond; Herrington and Curtis; Eodice et al.), and lifespan development (Taking the Long View; Prior; Roozen) to offer a model of writerly development and explore that model through two case studies.

III: Operationalizing the Writing Development Model

We define writing development in a similar manner to Curtis and Herrington, who argued that writing development was a “positive and persisting change and growth” (70). To this, we add that writing development also includes a growing expertise about approaching new writing tasks (College Writing and Beyond), effective use of metacognitive strategies (Gorzelsky et al.), a developing nuanced understanding of genre, audience, and rhetorical situations (College Writing and Beyond; Reiff and Bawarshi), and writing improvement over time (Oppenheimer et al.).

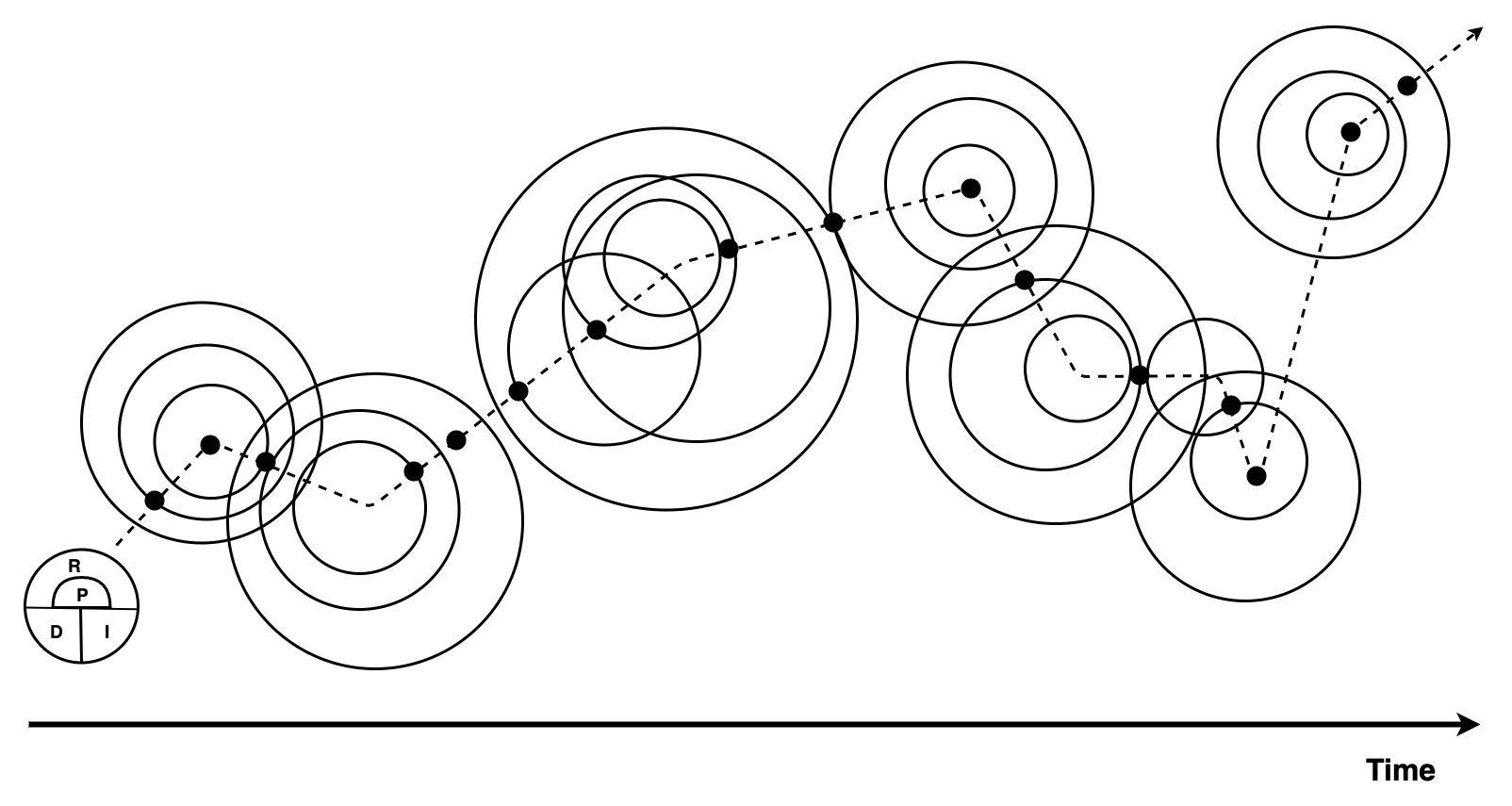

Our model draws attention to the complexity of the interaction between Key Events, Person characteristics, Contexts, and Time. As illustrated in Fig. 1, we recognize that each writer moves through Time across a myriad of Contexts. As they move, the writer brings with them a set of Person characteristics—Identities, Resources, and Dispositions—that frame how the writer interacts a key writing situation. Different Writing Events or Contexts may make Person characteristics more or less salient, and a writer may also be able to effectively mitigate or circumvent disruptive Person characteristics using metacognitive awareness. The interaction between a Person and her Contexts thus allow the potential for long-term writing development—which may or may not be realized. We now consider each of these italicized parts of the model in depth.

Figure 1. A Person moving through Contexts and Time.

Time refers to the lifespan across which writers develop. A writer often inhabits multiple nested Contexts in Time; some of these Contexts may be relatively stable over Time (a long-term workplace, for example) while some regularly change as Time passes (coursework by semester, for example). A writer’s development is always influenced by the Contexts in which writing happens and we see Contexts and writers as existing in complex ecologies which are dynamic (as any writing teacher knows, teaching the same first-year writing curriculum in four back to back classes can still lead to radically different classroom environments). In this way, this interaction of Writers, Contexts, and Time is ecological and shaped by these factors. A Writer experiences many such Contexts throughout their development both in and beyond school or work settings. Embedded in those Contexts are activities, rhetorical situations, and discourse communities that shape writing (which have been modeled and defined by the literature, see Beaufort, Operationalizing the Concept and Russell Uses of Activity Theory). We represent Contexts as nested because some of them overlap, encompass sub-Contexts, interact with one another, and influence the writer jointly (e.g., a writer takes courses that are embedded in a university, while also recognizing that each session of a course may offer slightly different experiences). Writing Events are specific writing experiences that shape writerly development and/or Events that do not directly involve writing but that may have an impact on writing development (e.g., a Person is encouraged to pursue writing a new project). Not all Events are salient; many may simply be rote or instrumental, completed and quickly forgotten.

Person: Resources, Dispositions, and Identities

Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s Biological Model of Human Development categorizes three types of Person characteristics as the most influential on the proximal process of development, including the following: first, Dispositions, which set proximal process in motion; encompasses internal qualities that are generative (supporting learning) or disruptive (detracting from learning). Dispositions are largely invisible, with each Disposition having different influential power; and are relatively stable over Time but can shift. Second, Resources, which consist of ability, experience, knowledge, and skills of the Person that function as developmental assets and liabilities. Third, Demand, which refers to the Person’s capacity to invite or discourage reactions from the social environment that can disrupt or foster proximal processes (Bronfenbrenner and Morris, Bioecological; Bronfenbrenner and Morris, Ecology).

Since one of the main goals of our model is to account for the role that Person/writer plays in the lifespan of writing development, we have adapted Person characteristics to align with contemporary research on writing transfer and writing development. In our model, we keep Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s concepts of Dispositions and Resources: during the writing development across the lifespan, writers possess and are shaped by various Dispositions such as self-efficacy, attribution, value, mindset, giftedness, ease (this list represents common Dispositions identified in the literature, as per Baird and Dilger; Driscoll and Wells). Meanwhile, writers have access to a myriad of Resources as they move along a path of development, e.g., prior knowledge, experiences, support, opportunities, individuals who can assist them, and so on. For the third Person characteristic of Demand, which is not well operationalized in literature, we operationalized it in our data analysis into two mediating factors, i.e., Salience and Metacognition, to capture the degree of interaction between the Person and Context as well as the Person’s agency to leverage their Person characteristics in such interaction. We will discuss our definitions and measurement of Salience and Metacognition in the next section in detail. Additionally, we added a new Person characteristic, Identities, because it is a critical feature identified widely within the study of writing, including in discussions of writing development and writing transfer (Field-Rothschild; Ivanič). Specifically, we use the plural form of Identity, drawing on the Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity (Jones and McEwen, A Conceptual Model; Abes et al., Reconceptualizing), to highlight the intersectional impact of Identities on writing development.

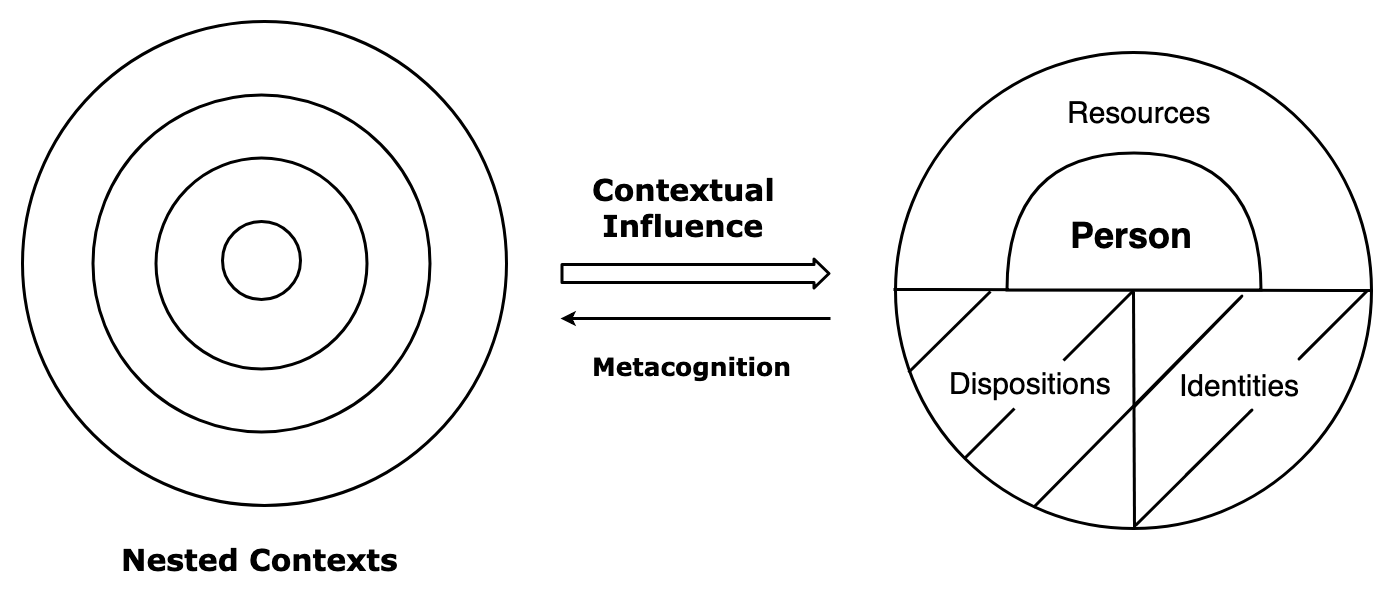

Figure 2. A Writing Event.

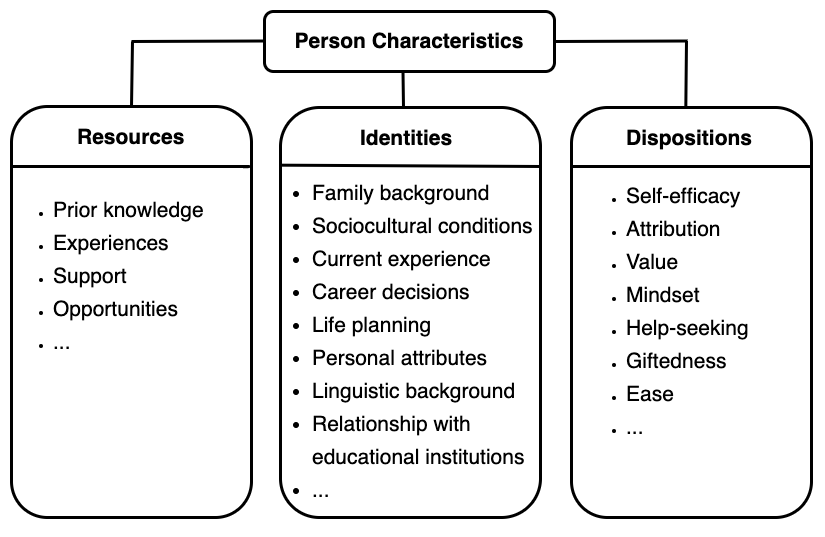

Next, with Fig. 2 and Fig. 3, we consider, in depth, the “Person side” of this model.

Figure 3. Three categories of Person.

Dispositions: Dispositions are individual characteristics that learners bring to Writing Events that shape short-term writing outcomes and long-term development. While not all Dispositions are well operationalized, the field of writing studies has recognized that a number of Dispositions are critical to writing success: self-efficacy (Pajares), attribution (Driscoll and Wells), ownership (Baird and Dilger), help-seeking (Williams and Takaku), self-regulation (Zimmerman), value (Driscoll and Wells), mindsets (Schubert), problem-solving and answer-getting (Wardle. Creative Repurposing), and ease (Baird and Dilger), among potentially many others.

In their discussion of Dispositions, Driscoll and Wells offer four key factors that shape writing Dispositions:

-

Dispositions are not intellectual traits (knowledge, skills) but “determine how those intellectual traits are applied.”

-

Dispositions “determine students’ sensitivity toward and willingness to engage in transfer.”

-

Dispositions can be developmentally generative (support short-term success and long-term development) or developmentally disruptive (disturb short term success and long-term development).

-

Dispositions are “dynamic and may be context-specific or broadly generalized” (par. 18-25).

Baird and Dilger note how a “powerful” Disposition may override a weaker Disposition (706), particularly a weaker Disposition that is in the process of development (in our model, we see this possibility as tied to Salience and Metacognition, below). Baird and Dilger acknowledge that Dispositions change and shift frequently depending on Contexts and individuals. Driscoll and Powell note that certain Dispositions may be disruptive in the short run but generative in the long run and vice versa. In sum, Dispositions are complex, contextual, and influential.

Resources: Resouce is a catch-all category to describe the many kinds of “resources” that writers can draw upon in a particular writing Context. Bronfenbrenner and Morris define Resources as “biopsychological liabilities and assets that influence the capacity of the organism to engage effectively in proximal processes” (The Bioecological Model 812). Here, applying Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s definition in writing research and by extension, based in our data, we identify Resources to include both biopsychological liablities and assets as well as liabilities and assets more broadly: prior knowledge about writing, self, and learning; prior experiences (educational, personal, professional, civic); people (such as peers or family); opportunities (internship, training, part-time jobs), and support structures (such as writing centers or faculty). We have expanded Resources to include social networks and individuals that writers may have access to as part of their “Resources” as these were very prominent in our dataset as driving writing development for our student writers. We also notice that some writers may have access to abundant Resources, while others may have few—tying back to our “toolkit” metaphor, students’ access to Resources is often linked to socioeconomic status, educational background, and identity (Lu and Ai). In fact, we regonzie that sociocultural, sociolinguistic, and socioeconomic factors deeply shape all three of our Person categories.

Identities: Drawing on the Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity (Jones and McEwen; Abes et al.) and the work of Ivanič and Gee, we recognize the importance of Identity for writing development, a concept that was absent in the original Bioecological Model (Bronfenbrenner and Morris). Identities are fluid and dynamic processes with various degrees of Salience depending on the Context. With a core sense of self, different dimensions of Identities are driven by family background, sociocultural conditions, current experience, career decisions/life planning, personal attributes, and characteristics. Identities, particularly linguistic Identities, may be central to how writers develop over Time (Kells).

Mediating Factors: Salience and Metacognition

In our model, we operationalize Bronfenbrenner and Morris’s characteristic of Demand into two factors that mediate the interplay between a Person, Key Events, Contexts, and Time.

Salience: While all Person characteristics move with a writer, the Context has a strong influence on which Person characteristics may surface, and the interaction between the Person characteristics and Contexts, which disrupts or fosters proximal processes, may thus manifest with varying Salience. For example, we saw in our dataset that poor self-efficacy may only manifest for high stakes, challenging writing tasks where a writer does not feel supported, but not be present in a low stakes writing experience or when a writer feels that a faculty member is supportive. We note that this concept of Salience is part of why studying Dispositions has been challenging (Driscoll et al.). As not all Person characteristics manifest in every Writing Event, and thus, we introduce Salience to capture such variance. Salience is one mechanism that may bring certain Person characteristics to the forefront depending on the nature of the Event. Salience is also closely tied to Identity aspects of Person and may also have their grounding in other sociocultural factors present at the Time of the Writing Event.

Metacognition: Based on our data, we observed that Metacognition, a set of thinking skills concerning one’s own cognition and learning (Scott and Levy; Gorzelsky et al.), can influence how a writer navigates Person characteristics to invite or discourage reactions from Contexts. In our model, Metacognition is both an awareness (knowledge) of the influence of Person characteristics and the actions (regulation) taken to leverage generative Person characteristics and/or lessen disruptive Person characteristics. Metacognition may be more or less present for different writers at different points along their development and some writers may be more metacognitively aware than others. Metacognition has been well operationalized in the literature (Scott and Levy; Gorzelsky et al.).

IV. Methods

Our primary goal was to develop a theoretical model that operationalizes and explores the relationship of Person characteristics to longitudinal writing development, similar to the work that Beaufort did in operationalizing discourse communities. Thus, this section explores our dataset, data analysis, and the development of key aspects of the model.

Data and data collection. Data for this study comes from an ongoing longitudinal study on learning transfer involving 13 students over a nine-year period (at the time of writing, 272 writing samples and 97 interviews over nine years). Participants were initially recruited from 18 sections of first-year writing their second semester in their freshman year at a regional research university. Data collection included yearly 60-minute interviews and writing samples. Participants were followed in most cases until one year past graduation. Interviews with participants discussed writing experiences in coursework, perceptions of writing transfer, writing process, Identities and Dispositions, and the specific writing processes surrounding the two writing samples.

Model development and member checking. Our model development was an iterative process that involved multiple rounds of data analysis, theorizing, and case study selection. One challenge with longitudinal studies is representing both depth and breadth (Huber); thus, our exploratory qualitative analysis focused on adapting and building the model using the broader dataset and then selecting appropriate case study participants to illustrate key aspects of the model. Qualitative case study research was used because it is, as Remler and Van Ryzin describe, “particularly useful and well-suited to discovering important variables and relationships, to generating theory and models, particularly uncovering possible causes and causal mechanisms” (60).

Thus, we began by asking a single question: what factors influence students’ writing development over Time? Researchers read the interview data for all participants for all years and wrote analytic memos for each participant, using Saldaña’s approach to qualitative research, and noting key developmental moments. After this round of analytic memos, we recognized the usefulness of the original Bioecological Model of Human Development (Bronfenbrenner and Morris) for accounting for interactions between Person, Context, and Time, but also the need for adaptation to account for critical Identity factors and other features observed in our data.

With our draft model in place, we began collaborative coding (Smagorinsky) and focused our analysis and coding on the interplay between Person characteristics and developmental moments for a subset of four writers as potential case study participants. This allowed us to further refine the model, including adding Salience and Metacognition. As we developed the model, we also conducted interviews in Fall 2018 and Spring 2019 with two participants enrolled in the study. This allowed us to engage in member checking (Remler and Van Ryzin), including with one of the case study participants. We selected our two case study participants, Ron and Nora (names are pseudonyms), because of their comparability, as described in the results. For these two participants, we coded all Person characteristics by year that were tied to participants’ development.

Salience and presenting Person characteristics. Not all Person characteristics are equally important for specific writing Contexts. Thus, we developed a Salience scale to help measure the impact of each Person characteristic on writers’ development (see Table 1):

Table 1. Person Characteristic Salience Scale

|

Salience |

Description |

|---|---|

|

++ |

Very generative Person characteristic that has considerable influence on writing development. The influence is present across multiple years and Writing Events. |

|

+ |

Generative Person characteristic that has influence on writing development. Appears in at least 2 key instances over multiple years. |

|

() |

Neutral Person characteristic. Characteristic is present, but doesn’t appear to influence writing outcomes. |

|

- |

Disruptive Person characteristic that has influence on writing development. Appears in at least 2 key instances over multiple years. |

|

-- |

Very disruptive Person characteristic that has considerable influence on writing development. Influence is present across multiple years and Writing Events. |

The Salience scale enabled us to represent Person characteristics as dynamic, contingent, and continually developing. As we analyzed the case study students, we mapped out how Person characteristics were directly related to the outcome of Writing Events and the growth of writers over Time. In many cases, participants themselves were able to self-identify generative and disruptive characteristics that drove or hindered their writing development. We present those characteristics in the results section as charts that summarize several years of salient Person characteristics and then, through case study narrative, describe key developmental moments.

We noted that different students have different levels of Salience for key Person characteristics and that this Salience can be strongly influenced by socioeconomic, sociolinguistic, and sociocultural issues. In our data, Nora’s socioeconomic Identity (working class) and linguistic Identity (speaking with a marked L2 accent) were both salient throughout her experiences, while for Ron (middle class) factors such as sociolinguistic or sociocultural Identity were invisible and not discussed, and yet, influencial, as we will describe.

Metacognition. Metacognition was another mediating factor that had considerable influence on how Person characteristics influenced writing development and individual responses to Events. In our case study analysis, we noted three outcomes of disruptive Person characteristics based on Metacognition:

-

A writer is aware of the disruptive Person characteristic but may not be able and/or willing to change (e.g., a writer knows that they procrastinate, but keep procrastinating even with ill outcomes).

-

A writer is aware of the disruptive Person characteristic, and over Time, works to engage in behaviors that help change or mitigate the disruption, often by levying other generative person characteristics (e.g., a writer knows they procrastinate, so they use help-seeking through visiting a faculty’s office hours to discuss an outline).

-

A writer is changing behavior over Time to promote more generative Person characteristics but does not indicate conscious awareness of this change (e.g., the writer used to procrastinate, but no longer does).

In the first two cases, the writer has metacognitive awareness about the disruptive Person characteristics, awareness which often, over Time, leads to long-term development and growth. In our model, we give more weight to a person being both aware and engaging in change (#2) (++) than to only change or awareness (#1 and #3) (+). This mechanism helps us track long-term growth.

We also noted that for the purposes of our analysis, any Person characteristic can manifest in a particular situation as developmentally disruptive or generative; the deciding factor is how it influences their specific writing in that moment and how it impacts the writer’s development over Time. In other words, we are offering a Context-based, Time-bound discussion of Person characteristics, rather than a Person-only frame. This will be explored in depth in the results below.

Limitations. We note several limitations associated with this study. First, the writing samples, while diverse and wide ranging, were primarily used to contextualize the experiences discussed in interviews. Second, our final two case study participants are representative of patterns found in our larger dataset; however, since we have only 13 participants in the study, additional work is needed to see if these same developmental factors play a role more broadly in other Contexts and settings. We also note that we have heavily focused our analysis on Person characteristics due to a lack of their discussion in the writing development literature and due to space limitations; as such, our analysis does not provide as full of an account for other potential developmental factors. Both of our participants are white, although Nora is a generation 1.5 immigrant from Russia who speaks with a marked accent, a first generation college student, and comes from a working class background. We recognize that additional work is needed to understand how this model applies to students with other socioeconomic, sociocultural, and sociolingustic backgrounds.

V. Results: The Model in Action

In this study, we focus on case studies of the longitudinal writing development of two writers, Ron and Nora, because of the representativeness and comparability of these two participants. The idiosyncrasies and commonalities of Ron and Nora offer a rigorous account for how different Person characteristics work together and influence writerly development in different Contexts across the lifespan. We spend a great deal more time on Nora’s account due to the nuance, complexity, and explanatory power, following with Ron’s more abbreviated account.

Nora and Ron were both students pursuing degrees with pre-med/medical emphases. We have nine years of study data for Ron; for Nora, we have six years of interviews and writing samples collected in the study, and she remained in contact with the researcher via email during the seventh and eighth years of the study. Ron is still enrolled in the study; this analysis represents nine years of data. One of the major differences between Ron and Nora are in the areas of socioeconomic status, first language and speaking with accented English, citizen status, and college preparedness, which influence many of the ways in which their development manifests (an issue we address more in the discussion section).

Overview of Person Characteristics:

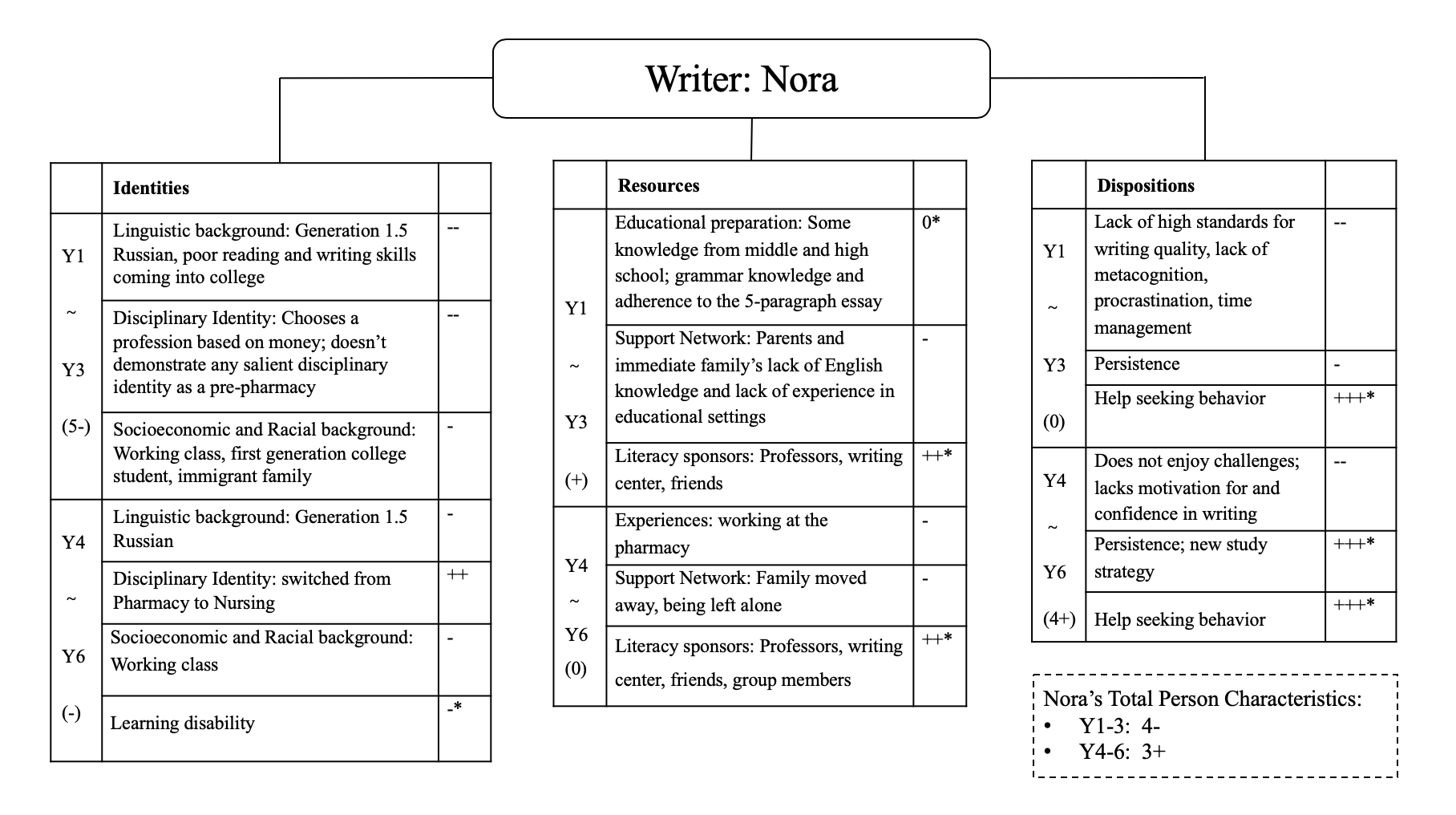

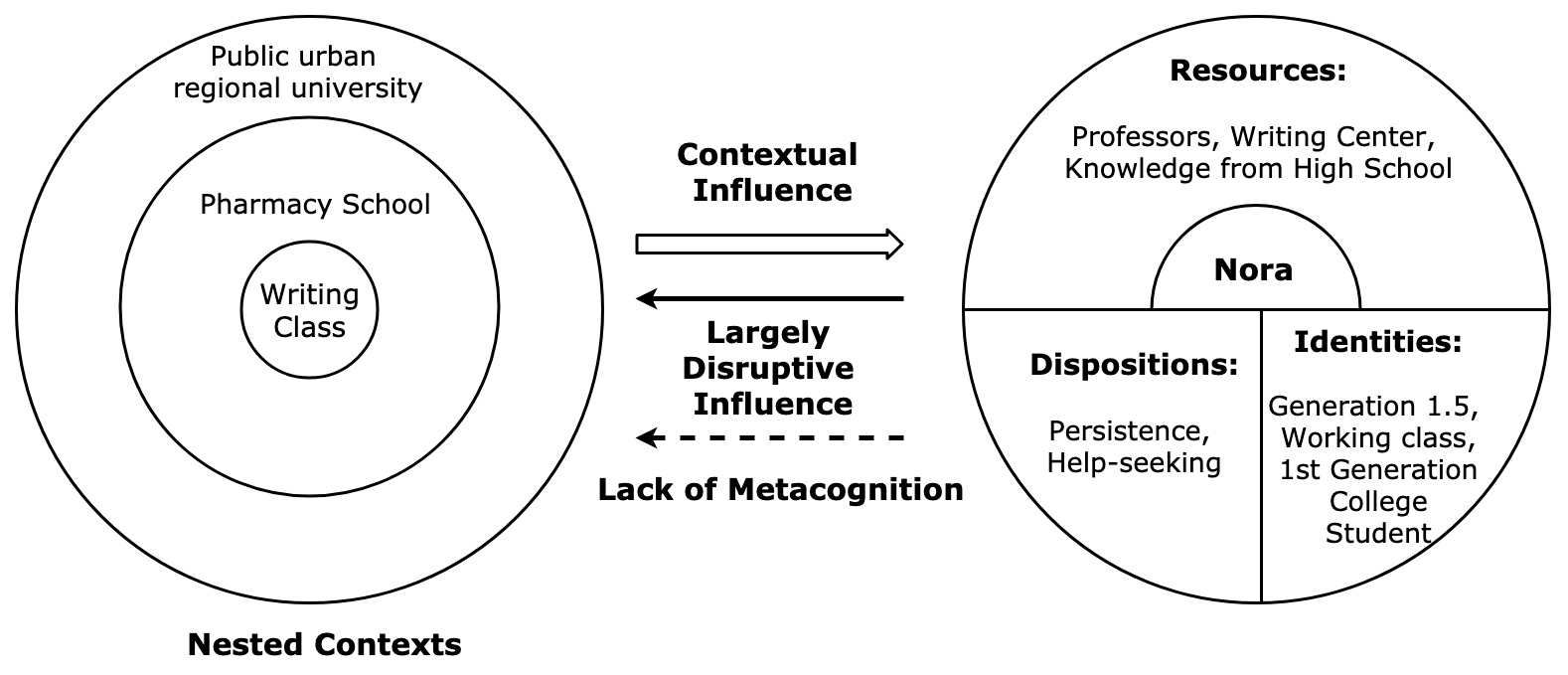

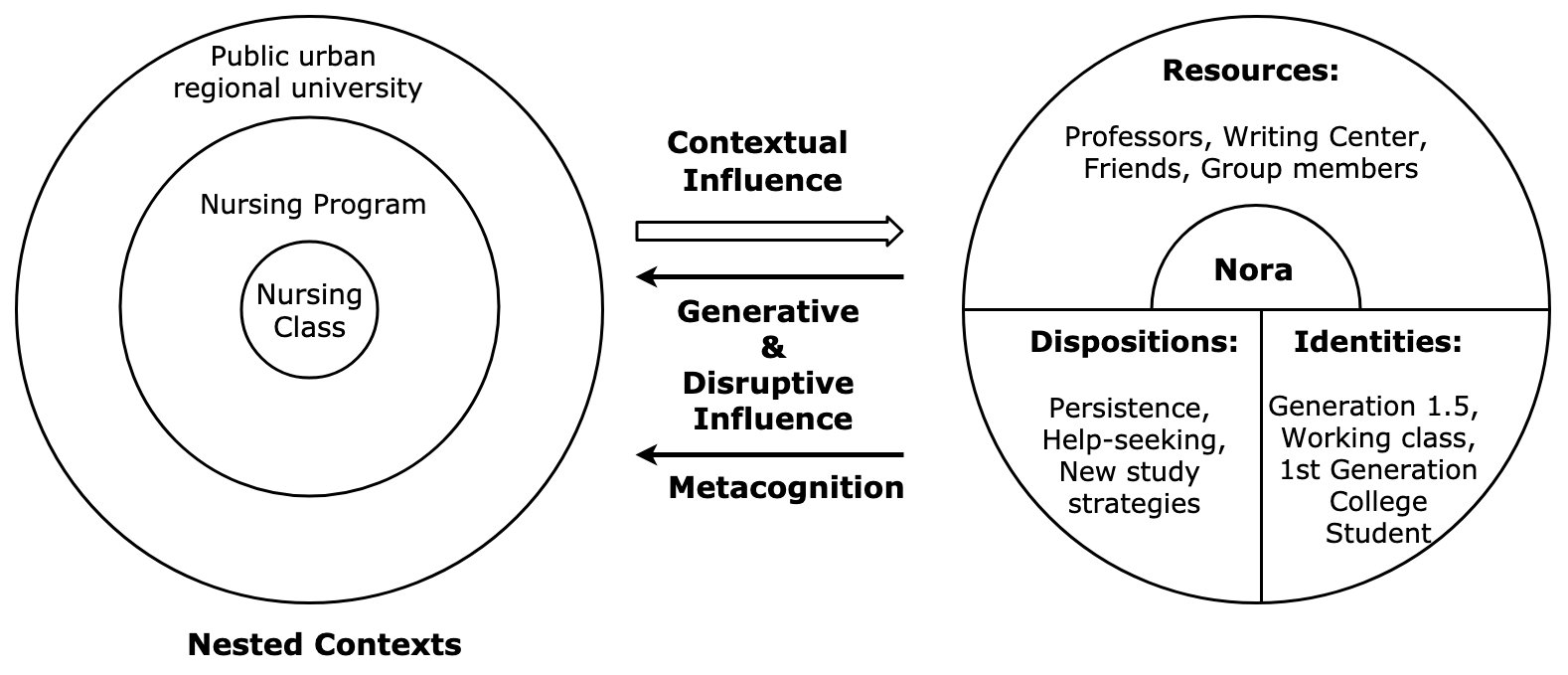

Fig. 4 offers an overview of how we measured Nora’s Person characteristics that influenced her writerly development during her six years of interviews in our study. In line with our coding glossary, during Years 1-3 of the study, Nora’s Person characteristics are generally quite disruptive (-4 total), offering her considerable challenge as a learner, and largely contributing to her lack of degree progress and writerly development. By the fifth year, a strong disciplinary Identity, growing writerly Identity, growing Metacognition, and new study strategies (particularly for literacy tasks) help her become a more successful student writer (+3). We now consider some of these Person characteristics in depth (see Fig. 5 and Fig. 6).

Figure 4. An overview of Nora’s Person characteristics.

Figure 5. Nora’s developmental moments: Y1-3.

Figure 6. Nora’s developmental moments: Y4-6.

Nora’s Identities. Nora is a generation 1.5 learner who immigrated to the United States from Russia with her family (her two parents and sibling) and who speaks with accented English. Nora’s social Identities include her linguistic background, her working class Identity, and her immigrant family: “I was born in Russia. We all moved from Russia. My brother, me, my mom and my dad. So when they moved here, they didn't know English at all” (Year 1). Nora’s salient social Identity as an immigrant with parents who were not speakers of English created obstacles for her literacy development. As she describes in Year 2:

“I don't even know where to start because I learned how to read very late and I was never a perfect reader at that. I always thought that was boring. And I never actually taught myself to read a book. And for [First-Year Writing], hope she never finds out about this but I actually never read any of her books...Because when I'm reading it, it’s just like I don't understand it.”

Nora’s lack of foundation of reading knowledge (Resources) caused her to struggle and thus hindered her successful completion of writing tasks and success in heavy reading-based science and lab courses. Nora’s first generation, immigrant Identity certainly impacted her ability to develop as a writer over Time.

Nora’s Resources. Nora came to college educationally underprepared and was categorized as a developmental writer by the university’s placement process and, as noted above, has what she herself calls “weak” writing skills (confirmed through her writing samples). Nora indicates that her prior knowledge about grammar and writing a five-paragraph essay served her well during her early college years. However, as we will explore below, even though such prior knowledge helped Nora transition into college writing, Nora seemed unable to move beyond these strategies—even when such movement was required—during her first three years. Another Person quality that Nora brings with her is undiagnosed ADHD (Attention Deficit Hyperactivity Disorder), which, after diagnosis, she identifies in our interviews as extremely disruptive of her education.

Nora does not have social Resources to draw upon; her friends and parents were unable to offer her knowledge or advice due to their lack of experience in higher education. In Year 4, Nora’s parents lose their jobs and her family moves away from the state, leaving her to sell the house and deal with the family’s belongings. While this offers her short-term stress, by the fifth and sixth year of the study, Nora reports gaining a stronger sense of independence and motivation from the experience, strengthening those Dispositions (and demonstrating, in part, the interwoven and ecological nature of writing development: how Person characteristics are shaped by Contexts and Time and how developmental factors beyond writing can shape writing development).

Nora’s Dispositions. Nora’s most generative dispositional characteristics are her help-seeking behavior, motivation, and persistence. It is likely that without these she would not have finished her degree successfully. Nora’s motivation and persistence are largely shaped by her working class Identity and challenged family life, which she routinely discusses. When asked about her motivation to persist in college in Year 3, she says: “I think I am because my parents they looked down to me but look up now... they really want me to finish this because they don't want me to end up like them.”

During every interview throughout the six years of our study, Nora reported proactive and persistent help-seeking for writing and other challenges, including help from professors, peers, and the writing center. Further, Nora demonstrated extreme amounts of persistence, even in the face of considerable difficulty. While this often led to her “pushing through” (Year 2) difficult tasks and challenges, we cannot list her persistence as wholly generative, even though this Disposition is typically considered as such. Nora’s persistence is what leads her to take the same courses over and over again that she continues to fail to try to complete her pre-pharmacy major. This extended her graduation time to eight years and hindered her development as a writer, as we now describe.

Nora’s Larger Development and Disciplinary Trajectory

Nora’s working class, immigrant Identity intersected with her career trajectory, which had larger developmental consequences for her as a writer. Nora selects pre-pharmacy as her major based on her parents’ encouragement due to socioeconomic reasons: “they have those credit card bills, phone bills...what field they want me into obviously is because of money because pharmacy is no secret, [pharmacists] make a lot of money” (Year 2). Despite her help-seeking, Nora’s working class Identity and persistence means she spends her first four years at college in a major that she could not effectively complete, continuing to repeat and fail prerequisite science courses, including organic chemistry I and II, anatomy and physiology, and calculus, all of which she took no less than three times each, never passing. Finally, in her fifth year, with no progress on her degree, she changes her major and enrolls in a nursing BA program. After making her transition to nursing, she looks back on the pharmacy choice and says, “But my parents kind of prodded, pharmacy, pharmacy, you would make good money, you’ll make good money. I just went the wrong route.” Nora ended up obtaining her Bachelors of Science in Nursing after eight years as a full time undergraduate student.

Because she never reached the advanced major-specific classes and because the repeated classes were large lecture courses, she was not able to engage in the formation of a disciplinary Identity nor compose disciplinary writing, which led her to make almost no forward progress on her writing development in the first four years of the study. By Year 4, she conveyed her concern at trying to help her cousin with high-school level homework and “losing her grammar” from lack of writing experiences in any coursework. This shows the relationship of Person characteristics, Contexts, and Key Events (or lack thereof). Additionally, she has a sociolingusitic impact; as Nora notes, her English language skills are “weak,” which contributes to her challenges in pre-pharmacy coursework.

Nora’s Writerly Development

For Years 1-3, Nora largely demonstrates “boundary guarder” (Reiff and Bawarshi) Dispositions with a strong emphasis on grammatical correctness (in part due to her sociolinguistic status). Her developmental trajectory can be evidenced by her responses to the question “What does good writing mean to you?”:

Year 1: “No grammar mistakes, it is long, reasonably long not like two pages....If you separate your paragraphs have a transition with grammar checks.”

Year 2: “I think good writing is not that the person does not make mistakes or not but the person uses words...I make mistakes in my last minute essays but it is like how they use words that are probably wouldn’t be here. They follow the dictionary next to them.”

Year 3: “Probably, the correct grammar like, using punctuations and stuff like that....Proper writing where mistakes are allowed but make sure you have your correct spacings.”

From these first three discussions of “good writing,” we can see that Nora is focused on grammatical correctness and avoiding mistakes, without demonstrating metacognitive awareness to help her deepen her understanding of writing, even in Contexts that demanded more nuanced understandings of audience and genre. Furthermore, she lacked Writing Events to engage in disciplinary writing and develop a disciplinary writing Identity, which further contributed to her lack of development and, thus, even further hindered her development.

After being immersed in only one semester of nursing coursework in Year 5, Nora demonstrates a much more nuanced discussion of “good writing” tied to a deeper understanding of purpose, genre, as well as discipline-specific conventions:

Nora: “That’s not like To Kill A Mockingbird or The Outsiders....[Nursing’s] completely different. That's situational.

[Researcher]: And what do you mean by situational?

Nora: The upcoming writing we're supposed to do, the essay, is about diagnosing a person. They have all these problem scenario. And we are supposed to diagnose them. We are supposed to start with what's the problem, why is the patient here, why are their nails blue, you know...When you research, you have hard evidence...You just put in your own words.

Thus, for the first time, in Year 5, Nora makes connections between writing and her nursing major, gaining genre awareness, and improving her writing in her discipline, reflected also in her nursing care plans. In Year 6 of the study, Nora speaks specifically about genre and positively about herself as a writer for the first time in the study, demonstrating a growing self-efficacy: “Nursing care plans, they are very, very different. I don’t mind doing them at all. Because I actually got really, really good at them.” Thus, once she is immersed in a disciplinary Context and taking on a disciplinary Identity, she begins shifting her understanding of good writing as “situational” for her nursing profession, indicating specific purpose and technical writing skills for nurses—and recognizing she can be “good” at writing for the first time. In Year 6, Nora’s understanding of the genre of the nursing care plan was expanded through help-seeking, learning field-specific language, and using nursing Resources. In this way, we can see Nora’s emergent metacognitive awareness of writing and disciplinary Identity not only influenced her disciplinary writing in a generative way, but also improved her writing self-efficacy (Disposition). Thus, through this example, we can see the role that Identities and metacognitive awareness play in shaping writing development.

Additionally, for the first four years of the study, Nora had an undiagnosed learning disability, ADHD. Nora’s gaining knowledge about ADHD enabled her to change her study habits and get medication. Through her increasing metacognitive awareness, Nora was able to mitigate the disruptive influence from her ADHD and alter her study habits. Nora notes that as part of learning about her ADHD, she was forced to consciously develop study strategies for reading difficult texts: “I read the notes, I read my own notes. I go back into the book and I follow, I highlight, I read. And that's what I think is, like that, I changed my study habits.” (Year 5). Thus, despite the disruptive Person qualities, Nora’s changed disciplinary Identity, mediated by her growing metacognitive awareness, brought about a crucial generative influence in her literacy practices—and eventually allowed her to develop as a writer.

Nora’s writerly development is also manifested in her writing. This first writing example comes from a lab report she completed for an Introduction to Health Science class in her first year, a prerequisite course for her pre-pharmacy major:

Question C: What do we know from previous studies? (25 points)

Some studies have showed that heart diseases are decreasing; unfortunately not all studies are correct. I have researched this topic in the American Heart Association and found out that there is an increase of cardiovascular disease and American women then in men. This is due to the aging population, also known as the baby boomers getting old. (Mosca).... In the journal Clinical Research, the article stated that people who have abdominal fat otherwise know as beard belly have a high chance of heart disease then the people who are just big all over the body. (Larsson)

Question D: What are the limitations of or problems with the study? (10 points)

When I interviewed some people, it was very obvious that most of them were not telling the truth about their life style. If they are active or lazy, so the score may be incorrect.

In Year 3, Nora offers a lab report for her Organic Chemistry I course where she has only minor notes and leaves the conclusions blank, saying she hadn’t finished the conclusion. When Dana asked her what a conclusion was and what was expected of her in writing, she said:

A conclusion is why did my product end up being, cause here where we had to go to titration. We took some of the sample. We had to mix it with other chemicals and then put through a titration. And then we had to reweigh it and see how much of the sample is left. And that was 3. And we had to do other calculations after we added it up.

We can compare the above to a segment Nora writes for a Clinical Assessment and Nursing Care Plan in her sixth year of the study introducing her instrument for addressing the elderly:

The SPICES tool is a framework of six common conditions the older adult experiences: Sleep, Problems with eating, Incontinence, Confusion, Evidence of Falls, and Skin breakdown. This screening protocol identifies the risk factors related to caring for older adult; it aids the nurses in preventing further complication when caring for the elderly. This tool also helps the nurses develop a nursing care plan for an actual problem and a potential problem the patient may be experiencing.

Care plan objective: The patient will demonstrate progressive healing of dermal ulcer, as evidenced by identifying the causative factors for pressure ulcers, identifying rationale for prevention and treatment, and participating in the prescribed treatment plan to promote wound healing.

In discussing this plan, Nora offers a detailed description for how to write a nursing plan, including citing material from a Nursing Diagnosis book: “We did not come up with that ourselves. That’s why under it, it has the information where I got it from....Because when we turn in out papers so we don’t steal other people’s knowledge. It’s their research, we research their research” (Year 6).

Further, comparing Nora’s writings in Year 1 and Year 6, we can clearly see her increased genre awareness, as evidenced in her more specialized and academic language use. That is, we see a dramatic improvement in understanding audience and purpose, as well as the ability to use disciplinary content, organization, and rhetorical strategies to meet genre conventions.

In addition, Nora demonstrates growing Metacognition about her needs as a learner, which enabled her not only to reconceptualize writing and move beyond the five-paragraph essay and grammatical correctness—but also to better navigate disruptive Dispositions that challenged her learning process. What is fascinating about Nora’s example is that we can see how closely her Person characteristics, including her motivation, Identity, and disciplinary Identity, influence her overall trajectory as a writer. But we also see how Person characteristics are shaped by Contexts over Time in disruptive ways, including her persistence to stay in a major for four years that she could not complete. This complex ecology of Person, Context, and Time shapes her and eventually allows her to master nursing genres and, most importantly, gain confidence with them.

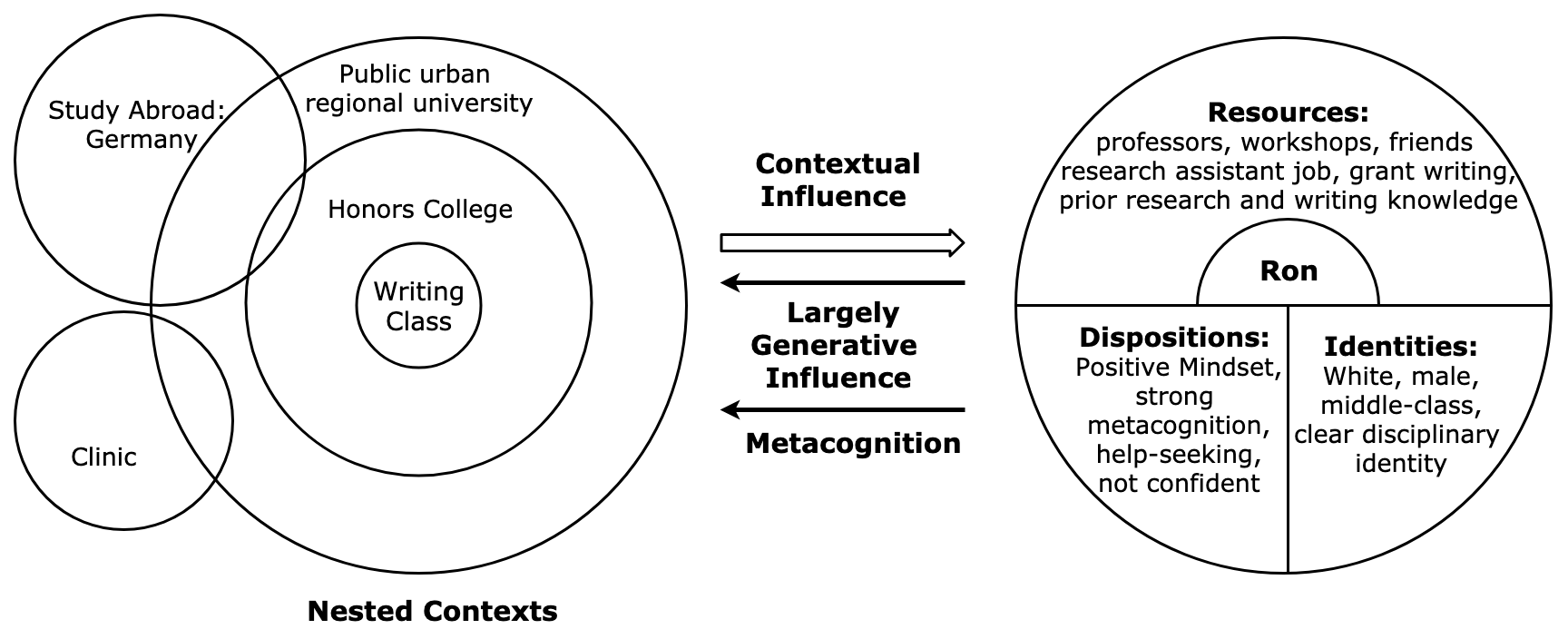

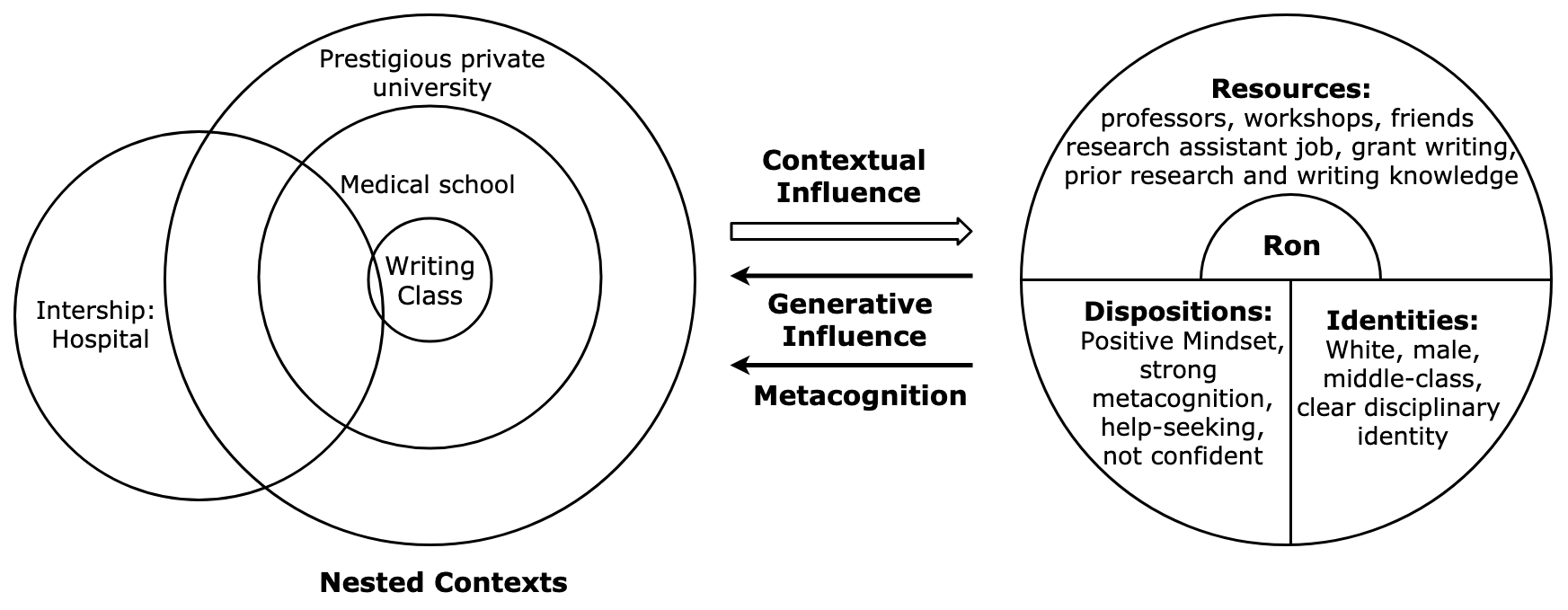

Ron

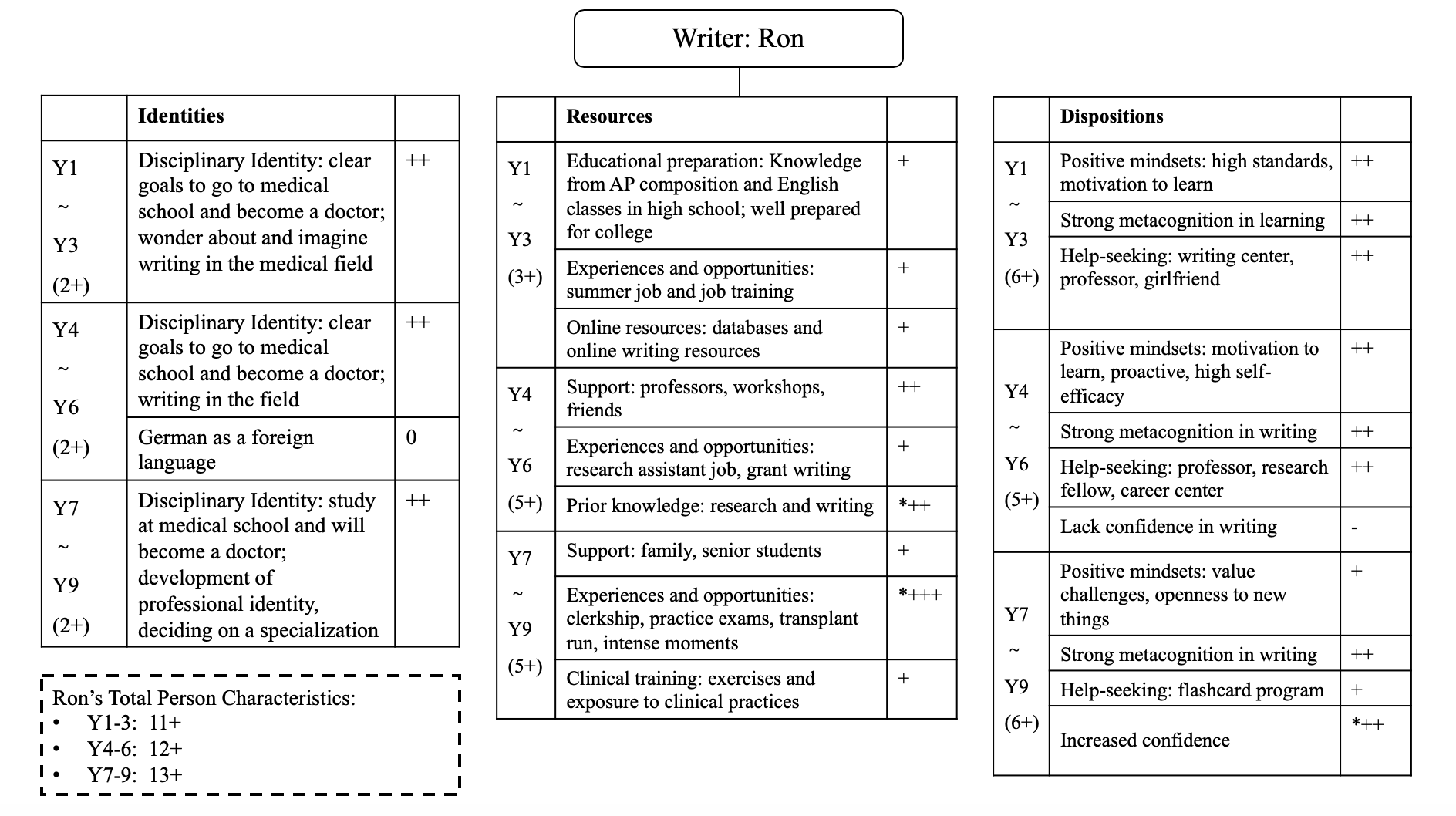

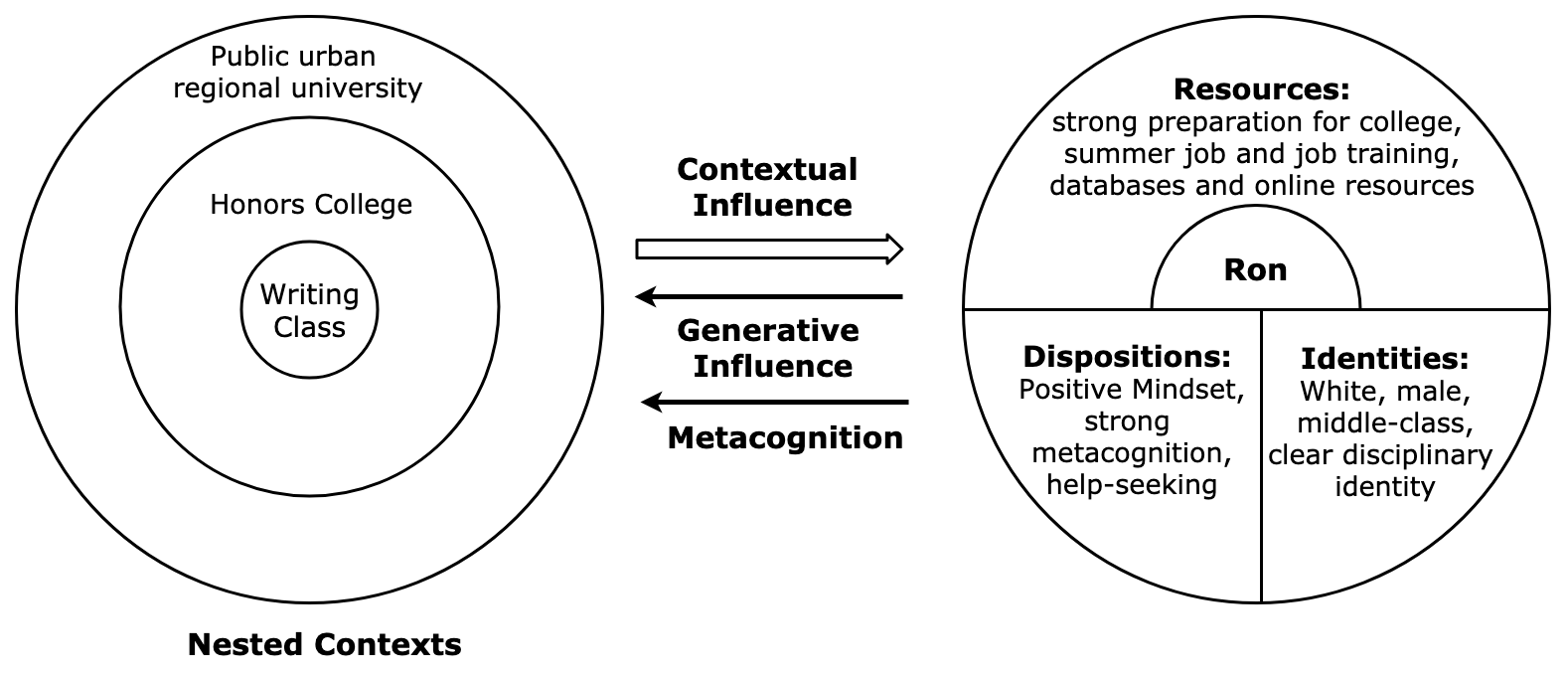

As a comparison of a student entering college with much more generative Person characteristics, mitigated by socioeconmic and sociocultural factors, we offer an abbreviated case study of Ron. Ron is a white student from a middle class background, who is a native English speaker, and who who was well-prepared leaving high school. Ron was admitted to the university’s honors college and, like Nora, had clear career goals to attend medical school. As he planned, Ron began his college study as a pre-med student majoring in biology (later, adding a second German major). Ron graduated in five years and went on to medical school at a prestigious university, where he is currently applying for residency programs. Throughout the nine years in our study, Ron demonstrated consistently his generative Dispositions such as positive mindsets, strong persistence, and strong metacognitive awareness; he also made active use of various Resources in different Contexts to aid his growth as a writer and learner (see Fig. 7).

Figure 7. An overview of Ron’s Person characteristics

Figure 8. Ron’s developmental moments: Years 1-3

Figure 9. Ron’s developmental moments: Years 4-6

Figure 10. Ron’s developmental moments: Years 7-9

Fig. 7 describes Ron’s Person characteristics that played vital roles during his nine years of writerly development in our study. With a multitude of generative Person characteristics: (eleven pluses during Years 1-3, thirteen pluses during Years 4-6, and eleven pluses during Years 7-9), Ron’s long-term writing journey demonstrates how he thrived by utilizing positive Dispositions in nurturing Contexts with supportive Resources across Time (see Fig. 9 and Fig. 10).

Identities: As a white male student with outstanding academic performance, many aspects of Ron’s Identities were never raised by him in his interview (unlike Nora’s, which were often central to her interviews). In fact, only his disciplinary Identity stood out as salient in Ron’s interviews. In his first year of college, Ron was already able to envision writing in the medical field and specific medical genres: “Well, I say my future because I plan on going to medical school, and I know I have to do a lot of writing. I’ve heard that...And in any research that I do will probably involve writing some reports on them.” Consequently, Ron’s career planning led him to become mindful of his writing development surrounding his professional Identity throughout all nine years of the study.

Resources: Ron benefited from prior writing knowledge from a high school education and a supportive (Resource) network that consisted of his family, professors, and friends. Additionally, Ron marshaled various Resources to aid his writerly growth, such as negotiating his professors’ expectations for his writing (all years), working part-time jobs in the medical field (Years 3 and 4), and help-seeking, drawing on others’ experiences to improve his application for medical school (Year 4). Ron’s successful writerly development not only depended on his access to a myriad of Resources but also stemmed from his ability to utilize such Resources strategically and creatively. In short, Ron was a proactive and resourceful writer who built his success on his generative Resources and Dispositions.

Dispositions: Ron demonstrated a range of generative Dispositions consistently throughout the nine years in our study, such as a positive mindset towards challenge (Dweck), strong motivation to learn, openness to challenges, and strong Metacognition.

Growth as a writer: Metacognition and Salience: One challenge that Ron faced was his confidence, which demonstrates both Metacognition and Salience in our model. Ron’s confidence remained undiscussed (not salient) during most low-stakes writing situations as an undergraduate. In fact, the first time Ron discussed confidence was in relation to medical school, in the process of his “gap year” during which he completed an internship with a local urologist: “I end up writing because someone's asking me to write and I think I would need a lot more practice to be able to call myself [pauses], to be really confident and I'm the whole I'm a ‘good writer’ type thing” (Year 6). However, it is not until he encountered the extremely high-stakes Context of medical school where his lack of confidence became salient. In his clinical experiences and written reflections (Year 8), he notes that his lack of confidence was often perceived as a lack of interest and engagement, and was noted by multiple faculty. Noticing how his confidence hindered his progress in medical school, Ron took proactive actions to manage and address his confidence issues (demonstrating high Metacognition).

One such high-stakes writing situation was when, as part of his hospital rotation, Ron had to write and deliver a medical case presentation for a room of experts—residents and doctors in Year 9. In addition to seeking help from a resident on his presentation, Ron reminded himself of a podcast that he had listened to years ago:

When it came to the presentation, it’s definitely something that’s difficult, because you don’t feel like the expert despite having looked everything up....I sort of like did the best that I could to put myself in the mindset that I probably know more about this specific topic than like most people in the room....I listened to this podcast a really long time ago: ‘fake it until you become it.’ Even if you aren’t ready mentally...just like force yourself to, to do it, until you fake confident. So, it’s definitely something I was probably trying to use while I was giving the presentation, and preparing for the presentation. (Year 9)

In this case, Ron overcame his disruptive confidence through metacognitive awareness and leveraged help-seeking behavior to deliver a well-received professional presentation. We also note here how this demonstrates Salience in the model—lack of confidence was present in Ron all along, but it wasn’t until the Context and Writing Event put pressure on it that it became an issue he had to address.

Despite their distinctive and sometimes even contrasting writing journeys, Nora and Ron had one thing in common: their writerly development was the result of the complex interplay among their Person characteristics, Key Events, Contexts, and Time. As Ron put it so compellingly when he reflected on his growth as a writer and learner in Year 9: “So taking those moments [of struggle] and trying to turn them into learning moments I think have been really big ones for me.”

VI. Discussion and Implications

Nora and Ron’s experiences demonstrate that writing development is a result of the interplay among at least six factors: a dynamic combination of Person characteristics, Metacognition, Salience, Contexts, Key Events, and Time. These Person factors are shaped by writers’ previous experience, as well as a host of sociocultural, sociolinguistic, and socioeconomic factors. Thus, we center our discussion around six key findings that examine the relationship of these factors and further discuss the nuance of the Writing Development Model.

Person characteristics substantially shape long-term outcomes for writing and learning over Time.

While Ron and Nora started out at the same university with similar goals{1} (attend medical school) and similar majors (pre-med and pre-pharmacy), their paths diverged quite quickly, with Ron leveraging generative Person characteristics to successfully complete the same courses and grow as a writer while Nora struggled to make any progress. The majority of Person characteristics that Nora brought with her were challenging to her development including her Identity as a generation 1.5 speaker of accented English, her procrastination, as well as larger issues tied to her Identity, such as her lack of non-university support networks for her learning. The mix of these disruptive Person characteristics with broader contextual challenges worked in concert and severely hindered Nora’s writing development during the first four years of the study. On the contrary, Ron’s socioecconomic background combined with a variety of generative Person charcteirstics (disciplinary Identity, educational preparation, help-seeking behaviors, strong support networks) supported Ron’s growth as a writer and disciplinary expert. While our analysis has focused on Person qualities and how these qualities may manifest as disruptive or generative in developmental Contexts, we recognize the interplay between broader sociocultural influences (race, education, immigrant status, class) on how these Person characteristics are expressed.

In the end, each student was “successful” and developed as a writer, in the sense that both earned degrees and gained full employment as a nurse (Nora) or entry and success in medical school (Ron). And yet, Nora’s path led her to a lower level of financial and professional success than she desired, and Ron’s path led him to his desired outcomes. As we explore the nuance of these developmental journeys, and the writing outcomes each were able to achieve while still undergraduates, they are worlds apart. The difference did not appear to be curriculum, the university support structures, or the courses: the difference in our data had to do with at least two factors. First was the generative and disruptive Person characteristics of each writer that were salient and that manifested throughout their journeys. Second, however, are their Identities: the generative Person characteristics Ron exhibited coincide with a privileged socioeconomic status, while those that Nora exhibited coincide with a less privileged socioeconomic and immigrant status, tying both to issues of Identity and that of Salience, and demonstrating how broader ecologies intersect with writers in key ways. Thus, as an ecological model suggests, we have to stress the importance of the interplay of factors on development, and the role that privilege and Identities play in the shaping and expression of these factors.

The Writing Development Model helps us showcase why certain students struggle and certain students are successful: it is an ecological and holistic approach that explores the intersection between specific Contexts, Events over Time, with a host of Person characteristics that have Salience within those Contexts. To return to our “toolbox” metaphor that opened this piece, we might say that Ron had a full toolbox with tools he knew how to use, while Nora’s toolbox was almost empty. Therefore, Nora’s and Ron’s two distinctive writerly development paths support Bazerman et al.’s (“The Lifespan”) claim that “writing development is variable; there is no single path and no single endpoint” (354-355).

Individual learners have a wide variety of developmentally disruptive or generative Person characteristics; the saliency and influence of these characteristics are shaped by Context.

Individual writers develop with a variety of Person characteristics (Identities, Dispositions, and Resources) that influence short- and long-term writerly outcomes. How these Person characteristics manifested were specific not only to the writer, but also based on the influence of Context. Nora’s persistence Disposition was, perhaps, the clearest example of this in the study. While persistence would normally be considered a generative Disposition, in the case of Nora, it had considerable negative developmental consequences for her in the first four years of the study, both for her time-to-graduation as well as her writing development. When we fast forward to the last few years she was enrolled in the study, however, this same persistence helped her complete writing tasks and be successful as a disciplinary writer. Likewise, Ron’s lack of confidence only became salient in the high stakes writing of medical school, which he was eventually able to overcome.

Metacognition (awareness of Person characteristics) can help writers navigate between Person characteristics, Contexts, and Writing Events.

Nora and Ron both demonstrated that Metacognition plays a critical role in how writers manage and navigate the interaction between Person characteristics, Contexts, and specific Writing Events. In our model, Metacognition can help reduce or eliminate a disruptive Person characteristic or strengthen generative Person characteristics further to compensate. As is represented in Figure 4, despite her considerable struggles, Nora’s Metacognition surrounding reading remained minimal. However, after being diagnosed with ADHD, she grew in awareness of her own needs. What is so compelling here is that this Metacognition didn’t just help her with reading but transferred to other writing strategies: she was more cognizant of her challenges (procrastination, poor reading skills, lack of focus) and she mitigated disruptive Dispositions by behavioral changes, such as utilizing her new study strategies and taking medication to help her focus. On the other hand, Ron’s case demonstrated how a writer with high Metacognition leveraged Person characteristics mindfully and strategically. With a clear awareness of his disciplinary Identity and career planning from the beginning of his college career, Ron marshalled Resources to his advantage to aid his growth as a writer. Furthermore, when he moved to medical school, he was able to draw on his prior knowledge that he had accumulated as an undergraduate to further his writing development, which is an example of how Ron’s Person characteristic of prior knowledge became more salient with the mediation of Metacognition. Throughout the study, Ron demonstrated consistently high Metacognition—and when faced with a Person challenge (confidence) he is metacognitively aware and engages in help-seeking.

What these case studies suggest is that one key aspect of supporting students—but especially those with less priviledged backgrounds—is teaching metacognitive strategies that can help students identify, understand, and mitigate disruptive Person characteristics by leveraging generative ones.

Person characteristics are dynamic and interactive; thus, they may influence, shape, or counteract other Person characteristics or be shaped by Contexts.

Just as Dispositions have been noted to be dynamic and Context-specific (Driscoll and Wells), based on our results, we suggest that nearly all Person characteristics are also dynamic, interactive, and can manifest in Context-specific ways and be shaped by those Contexts and Events. Nora’s help-seeking behavior is a good example here; she uses help-seeking to “make up” for the lack of other Person characteristics (including writing and literacy knowledge, limited English language mastery, family support structures, and more).

We also note that the three aspects of Person in this model function differently from each other in various writing situations. For our participants, Resources are used, leveraged, and drawn upon in a fairly conscious way. Identities are expressed, denied, or shaped and may or may not be as salient depending on the Context (Identity was salient for Nora and not salient for Ron, likely due to broader issues of privilege and socioeconomic status). Dispositions, as Bronfenbrenner and Morris note, function in powerful ways to drive development and are often driving forces in Writing Events.

Person characteristics are dynamic and may be learned, taught, and modeled.

As Nora’s learning strategies and ADHD suggest, Person characteristics are not static characteristics but rather manifest in dynamic and fluid ways. Even for more stable Identities or Dispositions, such as Nora’s working-class and immigrant background, we saw how these Person characteristics are managed, navigated, and shaped over Time. In some cases, such as Ron’s confidence building, direct interventions on the parts of teachers and mentors can help shift and shape Person characteristics. In other cases, one kind of Person characteristic can make up for another or influence others (a finding echoed by Baird and Dilger). Again, we see tremendous pedagogical opportunity to help studnets understand the impact and leverage Person qualities as writers.

Disciplinary Identities are salient factors for shaping writing development, and may help mitigate other disruptive dispositional factors.

Nora’s transition from pre-pharmacy to nursing, and her subsequent considerable writing development as a nursing major shows how critical specific disciplinary Identities can be in shaping writers’ long-term growth. In her first four years, Nora was exposed only to prerequisite courses and general education courses; these courses did not offer Nora any sense of professional Identity. During this time, Nora’s writing development is essentially stagnant. After only one semester of nursing courses, she had major positive changes in her disciplinary Identity and writerly Identity, where she is more specifically able to shift away from “correctness” into more nuanced understandings of genre, purpose, and audience. Ron’s writing development across nine years grew, supported by a strong disciplinary Identity as well as key sets of pre-professional experiences. Upon entering medical school, Ron’s disciplinary Identity evolved from imagined to an embodied one. We note that disciplinary Identities are not the only kind of Identity we saw drive these writers’ development; in the case of another participant in the study, her Identity as a lesbian offered her motivation to explore key issues through writing in disciplinary genres.

Cultural Identities may deeply shape writing development.

One of the remaining questions that arises from this data is the role of sociocultural Identity and how privileged Identities may shape other developmental factors. While the Writing Development Model explores the role of individuals in Contexts, our data provides limited direct evidence that broader cultural factors influenced both of our participants and the manifestation of their Resources, Dispositions, and Identities. Nora was able to articulate how her cultural and linguistic Identities shaped, and in some cases, hindered her development, while Ron’s sociocultural history remained—by his own discussions in our interviews—almost completely unmarked. With that said, it is certain that Ron’s educational preparation, along with his social class and ethnic Identity, undoubtedly contributed to his success, and studies on a much larger scale have explored the continual impact of privilege on educational achievement, including in the medical professions (Grumbach and Mendoza). Our goal in this study was not to explore how these Identities, Dispositions, or Resources were formed and shaped but rather, how existing Person characteristics were used and impacted writing development. We would encourage future researchers to take up questions of how Person characteristics may be impacted by socioeconomic, sociocultural, and sociolinguistic factors, with a particular emphasis on students with marginalized Identities, like Nora.

VII. Conclusion

Through the stories of these two writers, we see the power and importance of Person characteristics and how the critical interplay among Person characteristics, Key Events, Contexts, and Time—mediated by Salience and etacognition—work in concert to shape writing development over Time. Our model is useful for a range of research on teaching and the study of English; particularly, we offer a nuanced framework for investigating writing growth over longer time frames (more than a semester or year). Our model also adds another tool in researchers’ toolkits to help them map the relationship of socioeconomic status or other challenged Identities and writing outcomes. Finally, our model provides a useful set of tools for faculty teaching writing across the disciplines and working to support students’ long-term learning by helping students develop metacognitive awareness and leverage generative Person characteirstics. As this piece focused on a rather broad overview and exploration of the model, we encourage researchers to explore various aspects of how Person characteristics shape long-term writing development in different circumstances including, within, and beyond college writing courses, in disciplinary settings, and within public or workplace settings.

Acknowledgments: Dr. Dana Driscoll, Professor of English and Writing Center Director, would like to acknowledge the support of the College of Humanities and Social Sciences at Indiana University of Pennsylvania for funding this project. Dr. Jing Zhang, Lecturer at the Department of Foreign Languages and Literature at Shantou University, extends sincere gratitude to her family for their unwavering support throughout this research project, including Zhang Yunsheng, Yan Jie, Lai Cailan, Wang Liwen, and Wang Bao.

Notes

-

Ron was able to more fully articulate the goal of attending medical school, having a sense of the steps and pathways towards that goal. Nora had a more nebulous understanding of the steps, but both of them clearly indicated the desire to attend medical school. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Abes, Elisa S. et al. Reconceptualizing the Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity: The Role of Meaning-making Capacity in the Construction of Multiple Identities. Journal of College Student Development, vol. 48, no. 1, 2007, pp. 1-22.

Adler-Kassner, Linda, et al. The Value of Troublesome Knowledge: Transfer and Threshold Concepts in Writing and History. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/troublesome-knowledge-threshold.php. Accessed May 4, 2020.

Adler-Kassner, Linda, and Elizabeth Wardle. Naming What We Know: Threshold Concepts of Writing Studies. University Press of Colorado, 2015.

Anson, Chris M. The Pop Warner Chronicles: A Case Study in Contextual Adaptation and the Transfer of Writing Ability. College Composition and Communication, vol. 67, no. 4, 2016, pp. 518-549.

Anson, Chris M., and Jessie L. Moore, editors. Critical transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer. WAC Clearinghouse, 2016.

Baird, Neil, and Bradley Dilger. How Students Perceive Transitions: Dispositions and Transfer in Internships. College Composition and Communication, vol. 68, no. 4, 2017, pp. 684-712.

Bazerman, Charles, et al. Taking the Long View on Writing Development. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 51, no. 3, 2017, pp. 351-360.

Bazerman, Charles, et al., editors. The Lifespan Development of Writing. NCTE, 2017.

Beaufort, Anne. Operationalizing the Concept of Discourse Community: A Case Study of One Institutional Site of Composing. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 31, no. 4, 1997, pp. 486-529.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State University Press, 2007.

Bronfenbrenner, Urie, and Morris, Pamela A. The Bioecological Model of Human Development. Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, edited by Richard M. Lerner, and William Damon, John Wiley & Sons Inc., 2006, pp. 793-828.

---. The Ecology of Developmental Processes. Handbook of Child Psychology: Theoretical Models of Human Development, edited by William Damon, and Richard M. Lerner, John Wiley & Sons Inc., 1998, pp. 993-1028.

Curtis, Marcia, and Herrington, Anne. Writing Development in the College Years: By Whose Definition? College Composition and Communication, vol. 55, no. 1, 2003, pp. 69-90.

Donahue, Christiane, and Lynn Foster-Johnson. Liminality and Transition: Text Features in Postsecondary Student Writing. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 52, no. 4, 2018, pp. 359-381.

Driscoll, Dana L., et al. Down the Rabbit Hole: Challenges and Methodological Recommendations in Researching Writing-related Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 35, 2017, https://compositionforum.com/issue/35/rabbit-hole.php. Accessed May 4, 2020.

Driscoll, Dana L., and Roger Powell. States, Traits, and Dispositions: The Impact of Emotion on Writing Development and Writing Transfer Across College Courses and Beyond. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.com/issue/34/states-traits.php. Accessed May 4, 2020.

Driscoll, Dana L., and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyondknowledge-skills.php. Accessed May 4, 2020.

Dweck, Carol S. Mindset: The New Psychology of Success. Random House Digital, Inc., 2008. Elon Statement on Writing Transfer. 2015. Web. Accessed 23 Nov. 2018. https://www.centerforengagedlearning.org/elon-statement-on-writing-transfer/.

Engeström, Yrjö. Activity Theory and Individual and Social Transformation. Perspectives on Activity Theory, edited by Engeström, Yrjö, et al, Cambridge University Press, 1999, pp. 19-38.

Eodice, Michele, et al. The Meaningful Writing Project: Learning, Teaching and Writing in Higher Education. University Press of Colorado, 2017.

Field-Rothschild, Katherine. ‘I was a Writer, Even if Teachers Brought Me Down’: The Impact of WID-Oriented Curriculum On Students Writerly Identity Development. 2020. Indiana University of Pennsylvania, PhD Dissertation.

Gee, James Paul. Chapter 3: Identity as an analytic lens for research in education. Review of Research in Education 25.1 (2000): 99-125.

Gorzelsky, Gwen, et. al. Cueing and Adapting First-Year Writing Knowledge: Support for Transfer into Disciplinary Writing. Understanding Writing Transfer: Implications for Transformative Student Learning in Higher Education, edited by Jesse L. Moore, and Randall Bass, Stylus, 2017, pp. 113-121.

Grumbach, Kevin, and Rosalia Mendoza. Disparities in human resources: addressing the lack of diversity in the health professions. Health Affairs 27.2 (2008): 413-422.

Herrington, Anne J., and Marcia Curtis. Persons in Process: Four Stories of Writing and Personal Development in College. National Council of Teachers of English, 2000.

Huber, George P. Longitudinal Field Research Methods: Studying Processes of Organizational Change. SAGE Publications, 1995.

Ivanič, Roz. Writing and Identity: The Discoursal Construction of Identity in Academic Writing. John Benjamins, 1998.

Jones, Susan R., and Marylu K. McEwen. A Conceptual Model of Multiple Dimensions of Identity. Journal of College Student Development, vol. 41, no. 4, 2000, pp. 405-414.

Kells, Michelle H. Linguistic Contact Zones in the College Writing Classroom: An Examination of Ethnolinguistic Identity and Language Attitudes. Written Communication, vol. 19, no. 1, 2002, pp. 5-43.

Lu, Xiaofei, and Haiyan Ai. Syntactic Complexity in College-level English Writing: Differences among Writers with Diverse L1 Backgrounds. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 29, 2015, pp. 16-27.