Composition Forum 49, Summer 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/

Tacit Knowledge, Reading Practices, and Visual Rhetoric: A Feminist Application of Eye Tracking and Stimulated Recall Methods on Comic Books

Abstract: Discourse-based interviews (DBIs) uncover tacit knowledge within written composing processes. Existing visual research methodologies offer tools for a necessary expansion of DBI to the study of tacit knowledge in visual and multimodal texts. This article outlines a feminist application of eye tracking as a visual research method used in combination with stimulated recall interviews to study tacit knowledge within college students’ reading practices of comic books. Study participants read excerpts from two female superhero comics while eye tracking equipment recorded their eye movements. In a later interview, participants watched video clips of their recorded eye movements overlaid on the comic book excerpts and reconstructed their reading processes. This article summarizes major findings from the study, including impacts of rhetorical genre expertise, gender, and comics culture on participants’ reading practices. The study demonstrates that eye tracking combined with stimulated recall interviews uncovered tacit knowledge that participants accessed as they read comics.

In this article, I outline my application of Lee Odell, Dixie Goswami, and Anne Herrington’s concept of tacit knowledge, as adapted from Michael Polanyi, to a study that uses eye tracking and stimulated recall methodologies to examine the comic book reading practices of college students. Odell, Goswami, and Herrington argue that discourse-based interviews (DBIs) offer an effective method for uncovering writers’ tacit knowledge, especially in helping writers recall their understanding of the rhetorical situation surrounding non-academic writing tasks (223). Odell, Goswami, and Herrington explain tacit knowledge within composition processes as knowledge that “writers can use... without having to formulate it consciously each time they write” due to repetitive usage (223).

Odell, Goswami, and Herrington close their article with a comparison to “composing aloud” methodologies and conclude, “we think researchers should look for ways that several existing methodologies might be brought to bear on the same topic” (234). My research answers this call by tasking existing visual research methodologies with the study of tacit knowledge in relation to visual, multimodal texts. In my dissertation, I used recorded eye tracking videos as a visual form of memory cuing, or stimulated recall, to uncover tacit knowledge as part of the reading practices of comics.{1} Combining eye tracking with stimulated recall interviews offered a productive expansion of the DBI methodology into a multimodal medium that required readers to read both words and images. It also offered a feminist approach to uncovering tacit knowledge by facilitating self-reflexive and collaborative work in the context of a solo-authored research project.

I begin this application article by explaining the scholarly and personal motivations behind my study. Then I present my research methods and offer illustrative examples of the findings from my study, which indicate that tacit knowledge in comics reading processes is rhetorical in nature and relates to the participants’ level of rhetorical genre knowledge. In addition, I found that the participants’ comics reading practices were intertwined with their expectations about gender in the comics medium and that their level of genre knowledge affected how they analyzed gender in the comics. Finally, I found that the participants’ reading practices were influenced by their individual identities, including their expertise, their academic training, and their demographics, which impacted the tacit knowledge they accessed as readers. I conclude the paper by offering an overview of the types of data I was able to uncover through eye tracking and stimulated recall methods, particularly as they relate to tacit knowledge, while acknowledging some limitations of eye tracking.

Locating Tacit Knowledge in the Reading Practices of Visual Texts

My study shifts from studying tacit knowledge in writing, as Odell, Goswami, and Herrington did, to studying tacit knowledge in reading for two main reasons. First, I argue that understanding how readers read visual and multimodal texts is crucial for developing informed decisions about how to use visual and multimodal texts in composition scholarship and pedagogy. Mariolina Salvatori says that studying our reading practices can “provide us with valuable insights into the ways we think” (445). She argues that a critical part of writing instruction is investigating “not only what happens when we read but also how it is that we tend to construct one and not another critical response to a text” (450). In Salvatori’s formulation, tacit knowledge in reading leads directly to tacit knowledge in writing, and it makes sense to study both in tandem. In recent scholarship, Ellen C. Carillo has argued for reclaiming an understanding of reading and writing as interconnected tasks that composition scholars are well suited to analyze. She argues that “the emphasis that the scholars writing in the 1980s and 1990s place on self-reflexivity and (meta)cognition acknowledges the complexity of reading” (6) and forms the basis for her call to renew the study of reading and writing as interrelated forms of composition (8).

I also argue that our field currently relies heavily on an assumption about students’ pre-existing abilities to read visual and multimodal texts, though we have limited research to validate this assumption. In my study, I focused on the expectations for readers of comics. For example, consider the hybrid textbook/comic book Understanding Rhetoric: A Graphic Guide to Writing. Two rhetoric scholars, Elizabeth Losh and Jonathan Alexander, and two cartoonists, Kevin and Zander Cannon, collaborated to create a first-year composition textbook in comics format. Successful use of this textbook requires students to be able to read and make sense of comics in order to access the core instructional reading material for the class. Composition scholars also advocate for bringing comics into the classroom in order to teach specific composition and literacy skills. Dale Jacobs has long advocated for the use of comics as a tool for developing multimodal literacy. He argues that reading comics as multimodal texts means “we can shed light... on the literate practices that surround all multimodal texts and the ways in which engagement with such texts can and should affect our pedagogies” (183). Stephanie Vie and Brandy Dieterle advocate for using excerpts from comics as a part of critical literacy pedagogy in composition classrooms, because the visual nature of comics makes them “well poised” to examine the “ideologies that underpin the texts and technologies that surround us in our daily lives.” All of these pedagogical strategies rely on students being able to read and make sense of comics, even as Jacobs, Vie, and Dieterle acknowledge that effectively reading comics requires specific skill sets and takes time.

The field’s assumption that students already have some skill in reading multimodal texts, like comics, particularly troubles me in light of rhetoric and composition research about genre and expertise. Rhetoric and composition scholars have studied the distinctions between novice and expert readers and writers for decades, often concluding that experts demonstrate savvier rhetorical practices than novices. Christina Haas uses the term “rhetorical reading” to describe “recognizing the rhetorical frame that surrounds a text, or constructing one in spite of conventions which attempt to obscure it” (49). She found that novice readers, such as first-year students, do not consider such rhetorical concerns as the purpose for writing a text, the contexts surrounding a text, and the relationship between an author and a reader.

In a collaborative study, Haas and Linda Flower found that rhetorical reading connects to an understanding of reading as a “discourse act” in which each individual reader combines knowledge gleaned from the current text with prior texts and other sources of knowledge (168). Richard Haswell et al. suspected that the reader’s personal context could play an important role in readers’ abilities to use rhetorical reading strategies. The researchers ran a variation on Haas and Flower’s study, in which they asked participants to read and respond to a newspaper editorial that would allow readers to bring their own “repertoires,” a concept Kathleen McCormick defined as “bodies of cultural value, knowledge, and convention” (qtd. in Haswell et al. 13). Haswell et al. found that both experienced and novice readers used rhetorical reading strategies when they analyzed the editorial. These studies together suggest that rhetorical reading is a mark of expertise, but a reader’s ability to demonstrate rhetorical reading is contingent upon their familiarity with the genre of the text they are analyzing. These findings offer troubling implications for pedagogies that rely on all students to read visual and multimodal texts effectively enough to develop additional, complex writing and literacy skills as a result of their reading.

Feminist Application

My study demonstrates a feminist application of the eye tracking method to the study of comics reading practices and tacit knowledge. Odell, Goswami, and Herrington show an example of how DBIs allow a participant to access tacit knowledge about gender in relation to her rhetorical context when they note that an administrator sometimes signed her workplace writing with her initial, M, rather than her name, Margaret, because “she sometimes felt her writing carried more weight when a reader did not know whether the writer was a man or a woman” (231). I hoped that a visual methodology would allow participants to similarly access their ideologies about gender in relation to comics and connect those beliefs to their reading practices.

I hypothesized that gender ideology would factor into participants’ understanding of the rhetorical context for superhero comics, in part because comics frequently depict sexualized female characters, and in part because of a longstanding myth that the reading audience for comics is primarily, or even entirely, straight white men. This myth is inaccurate but powerful. Matthew A. Cicci argues that women have always been engaged comics readers, but some comics fans and creators push the narrative of an all-male fandom so that comics creators have “carte blanche to ignore female readership” and their specific concerns (194). Suzanne Scott explains that the fandom myth has the potential to become “self-fulfilling” when women stop reading comics, or never read them, because they perceive “comic book culture as inaccessible or inhospitable.”

As a straight, white female comics fan, I have experienced some marginalization in the comics fandom—usually in the form of being “tested” about my comics knowledge to prove my fan status—but I do not experience compounded forms of marginalization based on my sexuality or race or ethnicity. Deborah Elizabeth Whaley prefaces her book about Black women’s roles in the production of comics and within comics fandoms by addressing her own position as a Black, female comics creator and American studies scholar. She argues that she is a “Black woman in a fanboy world,” which continues to affect her and shape her scholarship. She says the fan spaces that surround comics, namely conventions and comic book stores, remain largely male and white, and “these sites are difficult for women of color to penetrate.... I have never seen anyone in a comic book store who shares my ethnic and gender identity” (ix-x). Whaley notes that every layer of identity that does not comport with the myth of the straight, white male audience creates another barrier to feeling welcomed in comics culture.

I hypothesized that the myth about comics audiences would factor into participants’ tacit knowledge as they read and attached critical value to their readings. I picked comics that to me, as a feminist scholar and frequent comics reader, coded as feminist and that I thought would provoke gender analysis from the study participants. I selected two female superhero comics, Batwoman: Elegy and Captain Marvel: In Pursuit of Flight, because both comics work against sexist tropes within the superhero genre and offer powerful, complex versions of female superheroes. I argue that both of these comics demonstrate feminist imagination as a form of rhetoric that persuasively uses creative texts to serve feminist goals. In an introduction to an edited collection on “thinking through feminism,” Sara Ahmed et al. explain, “the feminist belief in future possibilities involves rethinking histories of our relations to the body, to sensory perception, to knowing and to politics... [The] work of imagination allows an opening or fissure in the past, through which we may realise a different future” (7). Thus, whenever feminists engage in feminist thinking, they must be creative enough to see the past differently and/or envision different possibilities for the future. They must also be rhetorically competent enough to firmly grasp timeliness by responding both to present conditions and improving on conditions extending from the past. I argue that the Captain Marvel and Batwoman comics in this study do this work. The texts invite readers to read and engage imaginative possibilities for more feminist depictions of female superhero characters and better responses to the concerns of female comics fans. I also believed these comics would serve a self-reflexive purpose, by allowing me to compare my feminist reading of the texts with the responses provided by the participants in my study.

Eye Tracking and Gaze Replays

Given our field’s findings about reading and expertise, and my knowledge about comics culture and its effect on readers, I wanted to study how college-aged students read and respond to comics, and I wanted to learn about the connection between their physical practices (what they looked at) and their analysis of the texts. In a methodology special issue of College Composition and Communication, Chris Anson and Robert Schwegler invite composition scholars to expand reading and writing research in the digital age with eye tracking, a method that uses infrared sensors to track a reader’s or writer’s eye movements and produce a digital map called a “gaze trail” (153-154).{2} Anson and Schwegler’s article suggests that tacit knowledge can be a key component in reading processes. They claim that most readers are honestly unaware of what their gaze trails look like as they read over a page. Most readers will fill in the content of a page based on a quick scan over and around the full page, rather than moving their eyes as they might expect, i.e. steadily from left to right, across each line of text, down a page (Anson and Schwegler 152). Since readers do not need to know about their gaze trails in order to read effectively, we could consider this a form of tacit knowledge that could be unpacked with the help of memory-cuing. Tacit knowledge in relation to reading has both cognitive aspects (like being able to fill in words by looking at only a few letters) and embodied aspects (including, but not limited to, the actual movements that readers’ eyes make as they move around a page.)

While eye tracking gathers useful data, I needed a complementary method that would help participants narrate and analyze their thought processes in order to access their tacit knowledge within their reading practices. As the introduction to this issue notes, the DBI is a form of retrospective interview and uses a form of cuing, based on offering alternative text choices within previously completed compositions. Odell, Goswami, and Herrington argue that providing alternatives and asking the writer to verbally respond to the alternatives is an effective method for stimulating “cognitive dissonance” (229) to uncover the tacit knowledge that writers use to construct an effective and appropriate piece of writing.

Anne DiPardo advocates for memory cuing in the form of “stimulated recall” as a tool for helping research participants expand their analysis of their own writing tasks. DiPardo interviewed students and tutors in a writing tutor program for developmental English students, and she used stimulated recall in her end-of-semester interviews by playing excerpts from audiotapes of tutoring sessions recorded earlier in the semester. She then asked the interviewees to reflect back on their statements and ideas. DiPardo found that students offered longer, more complex answers after they heard their recorded sessions (167). She offers a case study of a Mexican-American student named Sylvia who responded to standard interview questions by describing her experiences with the tutoring program as “pretty good,” even though DiPardo suspected that Sylvia had a more complicated experience. By using stimulated recall, DiPardo provoked deeper analysis from Sylvia, who “became both fascinated and reflective” when she heard the recorded sessions (174). Both DiPardo and Odell, Goswami, and Herrington make compelling arguments for using memory cuing to provoke metacognitive analysis, but neither stimulated recall nor DBIs necessarily work for multimodal texts that include visual components.

Therefore, I combined eye tracking with a stimulated recall methodology called gaze replay, which invites participants to remember and reflect on their reading and writing practices of visual or multimodal texts. An eye tracking study in education by Halszka Jarodzka et al. combines eye tracking and stimulated recall interviews to identify the strategies that experts and novices in biology use to “perceive and interpret visual stimuli” (146). The researchers first asked participants to watch four videos that showed the ways that different fish move. Afterward, the participants were shown a cue that the researchers called “gaze replay” that “consisted of the videos with the recordings of the participants’ own eye movements superimposed onto the video” (149). The participants were asked to examine their gaze trails and then explain what they were thinking when they watched the fish videos the first time. Jarodzka et al. argue that eye tracking enabled them to analyze the difference between experts and novices on a “perceptual level,” while the gaze replay interviews enabled them to analyze differences on a “conceptual level” (152).

Gaze replay addresses persistent concerns, such as those raised by Odell, Goswami, and Herrington, about research participants’ abilities to accurately access their own memories. Tamara Van Gog et al. posit that using a cued interview alongside eye tracking leads “to better results because of less forgetting and/or fabricating of thoughts” (238). Gaze replay puts less of the burden on participants’ memories of their choices, although in all fairness, it does not eliminate the problem entirely. Van Gog et al. also argue that cued retrospective reporting elicits data about multiple types of knowledge from study participants. In a study comparing different research methods for evaluating problem-solving strategies, Van Gog et al. coded the types of computer problem-solving knowledge that engineers verbalized during concurrent reporting (like think aloud protocols), retrospective reporting, and cued retrospective reporting. Van Gog et al. found that cued retrospective reporting elicited the widest range of problem-solving information from their participants, including the successful actions participants took to reach their problem-solving goals, the assessment steps and unsuccessful actions that were part of their process, and metacognitive explanations for how and why they took the various steps (242). Arguably, cued retrospective reporting, like gaze replays, enables researchers to get the most data possible about a study participant’s cognitive processes, including tacit knowledge.

In my study, gaze replay interviews factored into my feminist application by offering the study participants a chance to co-analyze their gaze trails, which allowed me to build collaboration into the design of this study. I remain mindful of Jacqueline Jones Royster’s call from Traces of a Stream for researchers to be self-reflexive and honest about their position either within or without the community they are researching. Royster argues that her afrafeminist methodology researching African American women “acknowledge[s] and credit[s] community wisdom,” and she explains that she sees the women in her study not just as subjects, but rather as “potential listeners, observers, even co-researchers” (loc. 3453). In my study, I wanted to respect the analytical expertise and differing perspectives that the participants brought to my study. I used gaze replays within stimulated recall interviews to make space for participants to co-construct meaning out of the eye tracking data. DiPardo found stimulated recall useful for similar reasons. She writes, “I had gathered that Sylvia held mixed feelings about [her tutor] Morgan, but without Sylvia’s own words... I would have been far more alone with the burden of interpretation” (176). Much like stimulated recall, the gaze replay method expands the role of data interpretation to my participants, rather than relying on my interpretation alone. It also encouraged me to be self-reflexive when my analysis differed from that of the participants in my study.

Study Design

My study took place at a large research university within a statewide university system. After receiving IRB approval,{3} I enrolled eight participants with the following demographics:

-

Gender: 2 male participants, 6 female participants

-

Race/Nationality: 1 African-American participant, 1 Chinese international participant, 6 white American participants

-

Sexuality: 4 heterosexual participants, 2 bisexual participants, 1 lesbian participant{4}

These demographics produced a wide variety of perspectives, even within a small participant pool. All eight participants were college students between the ages of 20 and 22 at the time of the study. They were all either English majors or minors at the time of their participation, and all worked in the Writing Center as trained writing tutors for at least one year by the time of their participation. These two factors created an appealing scenario in which I could assess how participants who were very skilled in critical reading and analysis would respond to the specific needs of reading comics. I used a recruitment questionnaire to assess demographic information about potential participants, and I recruited participants who represented a range of comics reading experience. The participants did not offer a representative sample of the student body, but my research was exploratory in nature and did not require a representative sample.

I completed two separate stages of data collection. In the first stage of data collection, the participants read excerpts from two collected volumes of serialized comic books featuring female superheroes: Batwoman: Elegy and Captain Marvel: In Pursuit of Flight. Participants read these excerpts in PDF format on a computer screen while an eye-tracking sensor followed and recorded their eye movements. Students read the pages at their own pace. They would then indicate to me with something like “okay” to let me know I could hit a button to move to the next page. This allowed students to keep their eyes on the screen without having to look away or lean forward to reach a mouse or keyboard, which could disrupt their gaze trail. After each participant finished a comic, he or she completed a survey that asked open-ended questions about the visual and narrative depictions of female characters in the comic books.

In the second stage of data collection, I showed each participant{5} four short gaze replays, less than a minute in length, of their own gaze trails superimposed over the comics pages. Participants were able to rewatch the segments if they wished. As they watched the segments, I asked each participant to retrospectively construct the thought process they believed they had used to originally read through that excerpt from the comic book. After they watched and responded to the segments, I prompted them to explain their survey answers with more depth and clarity and/or make connections between their gaze trails and their assessments of the comic book characters.

Eye Tracking Data

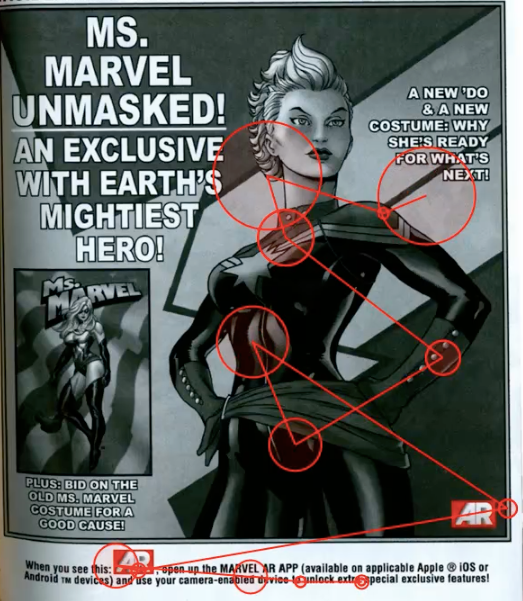

The eye tracking equipment recorded gaze trails as modeled in Figure 1, which shows part of the gaze trail of a participant named Natalie{6} reading In Pursuit of Flight. The comics portion of the image is a close-up of a large panel from the right half of the first double-page layout in the excerpt. This portion of Natalie’s gaze trail takes place 21 seconds into her reading of In Pursuit of Flight, so she has already read part of the page. The gaze trail for those earlier seconds has been removed from the screen in order to make the new saccades and fixations in the gaze trail easier to see. The visible gaze trail takes Natalie approximately five seconds to complete. Larger circles indicate longer fixations.

Figure 1. An approximately five-second segment of Natalie’s gaze trail from a portion of the first double-page layout in the Captain Marvel excerpt. It demonstrates the appearance of a gaze trail overlaid on a comic book page, with saccades shown as red lines and fixations shown as red circles of varying size corresponding to the length of the fixation.

The gaze trail here begins with a fixation, depicted as a red circle, over the text on the upper right-hand portion of the page. Next, there is a saccade as Natalie’s eyes move to Captain Marvel’s shoulder and face, where there is another, longer fixation, indicated by a slightly larger circle. Natalie’s gaze then travels to Captain Marvel’s chest, then to her left forearm, then to her crotch, and then to her stomach. There is a short fixation at each of these points. Finally, Natalie’s gaze moves to an augmented reality (AR) logo at the bottom right of the page, and then again to the corresponding explanation of the Marvel AR app associated with the AR logo at the very bottom of the page underneath the large panel in this image. Her gaze trail has short fixations in four places on the text as her gaze trail moves from left to right across the AR directions.

Interview Questions

In the interviews, I primarily used individualized interview questions that I generated after watching each participant’s eye tracking maps and reading their survey answers. I focused the individualized questions on survey answers or gaze trails that seemed confusing or unclear to me, which served my feminist goal of collaborating with the study participants to make sense of their own reading processes.

I had three shared questions for all the participants. First, I asked each participant if they felt they had read diffierently in any way because they knew they were participating in a study, and if so, how. Two novice participants in my study, Natalie and Nicki, said they were unsure since they did not have what Natalie referred to as a “baseline” for how they would normally read comics. More experienced readers varied in their responses, but there were two trends in their answers: First, they talked about some ways in which they felt they had read more carefully for the study. Multiple readers said they believed they had spent more time reviewing the images on the pages or taking more time to be sure they understood the plot, since they knew there would be survey questions later. Second, experienced readers compared the reading experience with how they would normally read a print comic book. For example, Erin said she would have liked to flip back and forth between the pages if she was reading these comics on her own. Her answer illustrates one limitation for the study. I had originally wanted to use an eye-tracking headset, which participants could wear while they read a hard copy comic book. However, the faculty member on my dissertation committee who advised me on eye tracking cautioned me against the headset. He said it would be difficult to get clear fixations on small details on the pages, and it would also be difficult to compare readers’ gaze trails without a fixed sensor. This meant I had to use a fixed eye tracking sensor on a computer screen to get the best data, but that removed some of the physical components of the participants’ usual reading experience. Some participants noted that they had felt the need to remain conscious of their posture for the sake of the eye tracking equipment, which they would obviously not do when they were reading outside the study. This means that the eye tracking method altered aspects of at least some of the participants’ reading practices.

Second, I asked all participants if they would be comfortable identifying their sexuality, and if they felt that their sexuality affected their reading of the comics. All seven interview participants did, and I discuss their answers in the findings below. Finally, at the end of each interview, I asked the participants if they had any questions for me. All the interview participants had questions, usually about the comic book characters or the larger plot that surrounded the excerpts the participants had read in the study. Several participants asked to see other portions of their gaze trails that related to questions that they had about the plot or the artwork. This meant that some of the participants aided in selecting additional gaze replays that contributed to their analysis and understanding of their reading process.

Findings

In my study, gaze replays were effective tools for achieving cognitive dissonance similar to the textual alternatives Odell, Goswami, and Herrington offered their participants. Participants in my study who watched their gaze replays were confronted with a seemingly erratic jumble of lines and circles that prompted them to reflect on their reading practices almost immediately. For example, Eli responded to his gaze trail on one page by laughing and saying, “I really was all over the place.”{7} On a different page with a lot of text, he seemed surprised by how little he looked at the images. When I asked if he was reading differently because of the study, he said that he was pretty conscious of what he was looking at during the first few pages, but he got comfortable by the time he was halfway through the first comic. Even then, he found his own gaze trails surprising.

All the participants implied or stated that comics required some form of reading expertise. Their beliefs are supported within academic comics studies where scholars argue that comics is a specific medium of text that requires specific reading practices. Comics scholar Hillary Chute explains that “comics doesn’t blend the visual and the verbal—or use one simply to illustrate the other—but is rather prone to present the two nonsynchronously; a reader of comics not only fills in the gaps between panels but also works with the often disjunctive back and forth of reading and looking for meaning” (452). Arguably, other media contain a similar presence of both text and images, but Chute and Marianne DeKoven clarify that comics relate words and images to the development of time in a way that is entirely unique to comics. They argue that images “comprise a separate narrative thread that moves forward in time in a different way than the prose text” (769). They explain that readers who want to fully understand the narrative in a comic must be able to read visual and verbal elements as related but not “unified,” and this is a particular skill developed by those who read the medium. Most importantly, expert comic book readers understand that this form of reading takes time: the reader “must slow down enough to make the connections between image and text and from panel to panel” (Chute and DeKoven 770).

Expert readers in my study accessed tacit knowledge about the conventions of the comics medium and their rhetorical functions as part of their reading processes. Eli offers an excellent example of an expert comics reader. He demonstrated familiarity with comics terminology, like panels and frames, and he explicitly referenced concepts from Understanding Comics by Scott McCloud, a foundational comics studies text. At times, he also compared his reading experiences during the study to other reading experiences he remembered from other comics. During his gaze replays, Eli explained that he typically used a kind of “trial and error” tactic to “figure out” the artwork and the story on each page. He referenced McCloud’s ideas of closure, in which readers try to make sense of the panels on the page and fill in the actions that must have occurred between the panels. Eli said that closure in “Captain Marvel was particularly easy to pick up” but less easy in Batwoman.

On a double-page layout in Batwoman with no words, he said that the color scheme made “it a little difficult to, as a reader, read” and said that these pages were “pretty intimidating the first time I read it.” Eli was the only participant who suggested that any reading difficulty he experienced could indicate a fault with the comics’ creators, as opposed to his own reading practices. He did not seem to expect that one pattern of reading would work best for every comic or even every page in a comic, but instead repeatedly mentioned that he was “trying to figure out” how to read each page correctly, while also acknowledging that “the way panels move down the page, or from panel to panel, are different between the artist and the writer” so finding one “correct” path might not even be possible. He noted that some of his analysis during his gaze replays “came after me thinking I figured out how to read it.” His assessment indicates his agency as a reader at the same time that it indicates that he is thinking of the words and images as related rather than unified, in line with Chute and DeKoven’s arguments about expert comics readers.

Agency, or the lack thereof, provides a major distinction between novice readers and expert readers. Expert readers felt comfortable with the slow, trial-and-error process of reading and analyzing a comic book, while novice participants consistently expressed awareness and anxiety about their lack of genre knowledge. For example, Natalie repeatedly identified herself as a novice comic book reader. She said that she was not sure if she could tell whether she read differently during this study because, “I don’t read many comics on my own.” She noticed a moment when she read downward on the left-hand page, even though it made sense to move to the right-hand page “chronologically.” She interpreted this as a lack of expertise, reminding me, “I don’t read many comics so that might be why I was a little bit confused.” She seemed to think that a more experienced comics reader would know to look across the double-page layout. This moment offers one good example of when the intended reading path might not be clear to any reader, regardless of expertise, but Natalie saw this as a personal mistake that reflected her lack of experience. Whereas experts tacitly accessed genre knowledge as part of their reading and analysis, novices felt keenly aware that they were unable to access important knowledge about reading the comics medium and that left them feeling unauthorized or unable to trust their reading strategies.

Using gaze replays as a cue also enabled me to assess connections between a reader’s comics expertise and their analysis of gender depictions in the comics. All of the participants discussed gender at some point in their survey and/or their interview responses, but their expertise affected how they discussed gender. For example, an expert comics reader named Erica framed her analysis in relation to other superhero comics and referenced key ways in which these comics appealed to her as a female reader. She explained that she could “sort of see [the imagery] being a little bit sexualized” in the comics but thought both of these comics were “moving away” from sexualized imagery as compared to other comics texts that she had read. She liked that Batwoman’s costume seemed designed to work in combat and was not “revealing a lot of skin.” With Captain Marvel’s outfit, Erica felt that seeing the suit in action, particularly “the mask that folds into place as she’s flying into space” highlighted the costume’s functionality within the narrative, as opposed to a purely visual choice designed for the audience. Erica analyzed the comics in relation to other superhero comics—as well as superhero video games, movies, and shows—where she argued that the costuming does not usually connect to the character’s own choices and goals. She explained that she was “used to male-driven protagonists” in the superhero genre and she “appreciated the change” to female protagonists. She also noted that in the TV shows, female characters were rarely featured, so she enjoyed seeing female characters hold the “spotlight.” Her expertise helped her locate feminist imagination in the comics by establishing improvement over previous comics as a key criterion.

Natalie, a novice comic book reader, offers a useful comparison to Erica, because they had different levels of expertise and came to different conclusions about the depictions of gender in the comics. Natalie, who was earning a minor in art history, offered multiple criticisms about the way that Captain Marvel was “overtly sexualized,” and during her interview, she asked to return to a specific page in Batwoman that she remembered because Batwoman was shown in a “sexualized” and “gratuitous” position while working out. Natalie praised some aspects of the imagery that appealed to her, like the way that Batwoman seemed to melt into the shadows, and she liked some of the character development in relation to the heroines’ traumatic pasts, but overall the artwork affected Natalie’s ability to enjoy the comics. She did not see them as feminist texts, and while she seemed curious about Batwoman’s storyline, she did not think she would read further in either series. She seemed to feel that superhero comics, more so than other comics, appealed to male readers and these beliefs had an impact on her choice to avoid superhero comics prior to this study.

Natalie’s answers during gaze replay illustrate how effectively gaze replay connected the participant’s physical reading practices with her analysis of the texts. For example, at one point during a gaze replay of a comics page in which Captain America helps Captain Marvel defeat a supervillain, Natalie laughed and said, “Wow. I notice that my eyes totally focused on [Captain America’s] butt like twice.” Natalie made other connections between her gaze trails and the images of the characters’ bodies as part of viewing her gaze replays. Farther on in the comic she notes that Captain Marvel’s legs are next to some of the narrative text and says, “It really drew my eyes across her body like that.” Gaze replay allowed her to see the words and imagery on the page in the context of the choices she had made as a reader, as well as the effects that the authors’ choices had on her reading practices. Natalie demonstrates astute visual analysis in her answers that offsets some of her lack of comics reading expertise.

Despite Natalie’s strong visual analysis of the texts, Natalie’s status as a novice reader becomes apparent as she addresses the rhetorical context for the comics. Unlike Erica, who frequently addressed the rhetorical context of comics within her stimulated recall answers, Natalie’s analysis during her gaze replays was focused more specifically on the textual evidence from these comics. Later in the interview, after she had watched her gaze replays, Natalie made several comments about her “prejudice” against superhero comics despite her lack of reading experience. She explained, “I do have some preconceived notions about how comic books portray women... I haven’t read a lot of them but you do hear a lot about violence and sexuality in comic books, especially in superhero ones.” When I asked her to explain where she got her ideas about the superhero genre, she attributed that knowledge to watching a limited number of superhero films and to having conversations with her sister, who was a frequent comic book reader. This became a trend within her answers: she repeated that she had not read superhero comics before, yet she frequently referenced strongly held beliefs about the norms for the superhero genre. These norms were almost never favorable and had direct connections to gender. When describing Batwoman’s fight scenes, she commented, “I assume [the comic] has a male writer just because I always assume that.” Unlike her careful and thoughtful analysis of her own gaze trails and the images on the comics pages, her analysis of the context felt more generalized and less evidence-based.

Gaze replays also played an important role in helping participants make sense of how their identities affected their reading practices. Erin and Natalie offer useful answers about the relationship between their sexuality and their reading practices. Both Erin and Natalie are bisexual, female participants, but Erin was an expert reader and Natalie was a novice reader. When asked whether she felt her sexuality affected how she had read this comic, Erin said, “I think [my sexuality] does come into play. I think I was a little bit conscious too, cause I’m like ‘Oh, I might look at things other girls might not.’” However, after asking to rewatch one of her gaze replays she said, “Maybe I retract my former statement and say, even if I was 100% straight, your eyes get drawn to [Captain Marvel’s breasts] because they’re just there. I could even say [her breasts] are ridiculously proportioned.” Natalie, who had previously mentioned her minor in art history, said, “I wouldn’t be surprised if [my sexuality] was a factor... I’m also trained in visual media like this [so I am] hyper-aware of how these characters are being portrayed.” Much like Erin, Natalie qualified her answer after rewatching one of her gaze replays. She still felt like her sexuality was a factor in her reading practices, but she noted that the comics layout also informed how she read. She said, “when I was watching this I was thinking about how her breasts are always very emphasized in the flight position she’s in. [Her breasts] are also just right next to her face all the time but also the placement of the text boxes... to get to the next [box] you have to visually cross over [her breasts] too.” She felt the sexualized imagery did not seem designed to appeal to female readers, whether they were attracted to women or not. She identified several sexualized positions in both Batwoman and Captain Marvel as “male gaze-y” and described an erotically charged fight scene between Batwoman and a female villain as “a male fetishization of same-sex female couples.” In the case of both these readers, they initially expected that their sexuality would affect the imagery that they looked at, but the gaze replay helped them contextualize their reading practices in terms of the specific texts that they read for this comic.

Conclusion

The findings from my study indicate that eye tracking in combination with gaze replays successfully achieves some of the same aims as discourse-based interviews: it provokes productive cognitive dissonance about a participant’s composition practices, and it invites readers to reflect on tacit knowledge about the rhetorical context for the texts in question. My study also matched some of the findings from Van Gog et al.’s study of different reporting methods. Through the use of cued retrospective reporting, the participants in my study accessed parts of their reading process that they viewed as exploratory, effective, and ineffective; they explained their choices; and they were able to access and vocalize some of their tacit knowledge. This wide range of data was useful for considering the complexity of reading as a rhetorical act.

My study suggests the depth of tacit knowledge that gaze replays can uncover. I initially hoped that eye tracking would tell me whether novices and experts looked at different parts of a comics page. Instead, I uncovered a much more complicated network of expertise, including which terms participants used to discuss their gaze trails on the comics page, how much agency they felt as readers, how much genre knowledge they were able to access, and how these related aspects of expertise affected their analysis of the characters and narratives. Furthermore, my findings indicate that readers’ tacit knowledge of the rhetorical context for the texts included gender ideology. Participants’ beliefs about gender are not easily separated from their rhetorical expertise or their physical reading practices. Finally, the study indicates that a participant’s identity, including their expertise, their academic training, and their demographics, contributes to the tacit knowledge that participants are accessing as readers.

My use of gaze replay as a feminist form of accountability and self-reflexivity also offered unexpected results about my own tacit knowledge. My original analysis of the Batwoman and Captain Marvel comics gives credit to the creative choices that the authors have made, but it also collapses my own interpretation of the comics with the content of the text and does not acknowledge the dual sources of feminist imagination that I am identifying in my reading. Within English studies, and particularly literary studies, this kind of collapse is a disciplinary standard that encourages scholars to focus on their own analysis of the text and make plausible claims based on a combination of textual evidence and a critical lens. My participants’ responses were not always so easy to collapse, and it would limit the results to try and do so. Most participants were able to locate something they considered positive about the depictions of gender in the comics, but the majority of participants also identified at least some imagery or plot points that they found stereotypical and sexist. This then raises a couple of difficult and fascinating problems for me as a researcher: Am I wrong in ascribing feminist imagination to the texts themselves? Does it matter if a text relies on patriarchal tropes and stereotypes if the readers are able to use feminist imagination as part of their analysis? When I consider my own reading of the comics alongside the readings of the eight participants in my study, it becomes clear that the source of imagination—whether from the creators or readers or researchers—matters. The participant with the analysis most similar to my own, identifying the comics primarily as feminist texts, also had a very similar identity position to mine: a straight, white female reader with scholarly training and personal experience in reading comics. It remains unclear how to best untangle the strands of imagination that connect a text with its authors and readers. Even so, this unexpected discovery helped me productively reflect on my own research and scholarship practices.

There are some important limitations to acknowledge about using eye tracking as a research method. Potential researchers should know that it is expensive to buy or rent eye-tracking equipment. Renting the equipment can cost thousands of dollars per month. Renting or buying the equipment may require separate purchases for the infrared sensor and the associated software. Ultimately, I was lucky that a professor on my campus was willing to lend me his eye tracking equipment and explain how to use it. Many scholars will struggle with access to the eye tracking method either because they do not have the connections to equipment on their campuses or the funds to access the equipment directly through an eye tracking company.

Second, eye tracking presents certain technical challenges. The eye tracking equipment in my study could not track readers’ eyes through glasses or contact lenses. It also required readers to sit a specific distance away from the screen, meaning a participant had to be able to read at a distance of about two feet without the aid of corrective lenses. Together, these aspects limited my recruitment pool significantly. The equipment also affected the participants’ reading processes since they had to sit fairly still at a certain distance from the computer screen, which did not fully duplicate their regular reading process. I then needed to calibrate each participant’s gaze to the equipment, and it took time to run multiple calibration tests. Given my lack of experience, I established what felt like a reasonable range of error in calibration, rather than aiming for perfect calibrations, to respect the time of my participants. This affected the type of data I was able to collect. In addition, I felt unable to perform quantitative analysis, which I had originally planned to do. Most researchers who use eye tracking for quantitative research work in teams of scholars because it is a labor-intensive process of data gathering and analysis. But team research would be inappropriate for a humanities dissertation that is expected to be the product of a sole author and researcher. This limitation may prove a similar challenge for other humanities scholars who want to use eye tracking in their research.

However, I believe that for researchers who are able to access eye tracking equipment, it is worth grappling with the limitations of the eye tracking method. Gaze replays offered an effective method for creating cognitive dissonance between a participants’ expected reading strategies and their demonstrated reading strategies. This dissonance prompted the participants in the study to reflect on why their expectations did not match the gaze replays they watched. Second, eye tracking with gaze replays created opportunities for me as a researcher to collaborate with the research participants on analyzing and understanding their reading practices. This offered me an effective way to meet the solo authorship requirements of a humanities dissertation while also meeting the ethical demands of feminist research. Third, the participants were able to produce metacognitive analysis and access tacit knowledge in their reading processes by watching their gaze replays, which allowed me to learn a lot about the complexity and messiness of participants’ reading processes. Therefore, I advocate for the use of eye tracking in combination with gaze replays and stimulated recall interviews as a useful method for investigating tacit knowledge in multimodal reading and writing. The method offers an important expansion of Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s DBI method to include visual and multimodal texts.

Acknowledgments: My deepest thanks to Drs. Laura Wilder, Tamika Carey, and Reza Feyzi-Behnagh for serving on my dissertation committee and helping me shape the research that provides a basis for this article. My thanks to Dr. Wilder, too, for her feedback on earlier drafts of this article, and Dr. Feyzi-Behnagh for training me in the eye tracking methodology and loaning me his eye tracking equipment. I am especially grateful to the writing center tutors who participated in my dissertation research. I also wish to thank the editors of this issue, Drs. Baird and Dilger, for their helpful comments on this article and their guidance through the publishing process. Parts of this research were funded by the Karen R. Hitchcock New Frontiers Fund Award (an Initiatives for Women Grant), as well as a Research Grant from the University at Albany Graduate Student Association.

Notes

-

Scholars who study comics use “comics” as a broad singular term for the medium that encompasses many types of graphic narratives, including comic books, graphic novels, comic strips, and webcomics. “Comics” can also be a plural term to indicate more than one comic. (Return to text.)

-

Per Anson and Schwegler, I use the following terminology: “Gaze trail:” the overall path that a reader’s eyes take as they move across a page; “Saccade:” a quick movement when a reader’s eyes move from one point to another on a page without pausing; “Fixation:” a stop or pause in the reader’s eye movements. (Return to text.)

-

My IRB protocol number was 16-E-002-02. (Return to text.)

-

One participant did not disclose their sexuality. (Return to text.)

-

One participant was unavailable for a follow-up interview, so I conducted interviews with seven of the original eight participants. (Return to text.)

-

All participants are identified by a pseudonym. (Return to text.)

-

The participants’ quotes have been lightly edited to remove verbal fillers, such as “um” and “kind of.” (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Ahmed, Sara et al. Introduction: Thinking through Feminism. Transformations: Thinking through Feminism, edited by Sara Ahmed et al., Routledge, 2000. pp. 1-24.

Anson, Chris M., and Robert A. Schwegler. Tracking the Mind’s Eye: A New Technology for Researching Twenty-First-Century Writing and Reading Processes. College Composition and Communication, vol. 64, no. 1, Sept 2012, pp. 151-171.

Carillo, Ellen C. Securing a Place for Reading in Composition: The Importance of Teaching for Transfer, UP Colorado, 2015.

Chute, Hillary. Comics as Literature? Reading Graphic Narrative. PMLA, vol. 123, no. 2, 2008, pp. 452-465.

Chute, Hillary, and Marianne DeKoven. Introduction: Graphic Narrative. Graphic Narrative, special issue of Modern Fiction Studies, vol. 52, no. 4, Winter 2006, pp. 767-782.

Cicci, Matthew A. The Invasion of Loki’s Army? Comic Culture’s Increasing Awareness of Female Fans. The Routledge Companion to Media Fandom. Routledge, 2017. pp. 193-201.

Deconnick, Kelly Sue, Dexter Soy, and Emma Rios. Captain Marvel, Volume 1: In Pursuit of Flight. Marvel, 2012.

Dipardo, Anne. Stimulated Recall in Research on Writing: An Antidote to ‘I Don’t Know, It was Fine.’ Speaking about Writing: Reflections on Research Methodology, edited by Peter Smagorinsky, SAGE Publications, 1994. pp. 163-181.

Haas, Christina. Learning to Read Biology: One Student’s Rhetorical Development in College. Written Communication, vol. 11, no. 1, Jan 1994, pp. 43-84.

Haas, Christina, and Linda Flower. Rhetorical Reading Strategies and the Construction of Meaning. College Composition and Communication, vol. 39, no. 2, May 1988, pp. 167-183.

Haswell, Richard H. et al. Context and Rhetorical Reading Strategies: Haas and Flower (1988) Revisited. Written Communication, vol. 16, no. 1, Jan 1999, pp. 3-27.

Jacobs, Dale. Marveling at ‘The Man Called Nova’: Comics as Sponsors of Multimodal Literacy. College Composition and Communication, vol. 59, no. 2, Dec 2007, pp. 180-205.

Jarodzka, Halszka, et al. In the Eyes of the Beholder: How Experts and Novices Interpret Dynamic Stimuli. Learning and Instruction, vol. 20, 2010, pp. 146-154.

Losh, Elizabeth, et al. Understanding Rhetoric: A Graphic Guide to Writing, 2nd ed., Bedford/St. Martin’s, 2017.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art, HarperPerennial, 1993.

Odell, Lee, Dixie Goswami, and Anne Herrington. The Discourse-Based Interview: A Procedure for Exploring the Tacit Knowledge of Writers in Nonacademic Settings. Research on Writing: Principles and Methods, edited by Peter Mosenthal et al., Longman, 1983, pp. 221-236.

Royster, Jacqueline Jones. Traces of a Stream: Literacy and Social Change among African American Women, Kindle ed., U Pittsburgh P, 2000.

Rucka, Greg and J.H. Williams III. Batwoman: Elegy. DC Comics, 2011.

Salvatori, Mariolina. Conversations with Texts: Reading in the Teaching of Composition. College English, vol. 58, no. 4, April 1996, pp. 440-454.

Scott, Suzanne. Fangirls In Refrigerators: The Politics Of (In)Visibility in Comic Book Culture. Appropriating, Interpreting, and Transforming Comic Book Culture, special issue of Transformative Works & Cultures, vol. 13, 2013.

Van Gog, Tamara, et al. Uncovering the Problem-Solving Process: Cued Retrospective Reporting Versus Concurrent and Retrospective Reporting. Journal of Experimental Psychology: Applied, vol. 11, no. 4, 2005, pp. 237-244.

Vie, Stephanie, and Brandy Dieterle. Minding the Gap: Comics as Scaffolding for Critical Literacy Skills in the Classroom. Composition Forum, vol. 33, 2016, https://compositionforum.com/issue/33/minding-gap.php.

Whaley, Deborah Elizabeth. Preface. Black Women in Sequence: Re-Inking Comics, Graphic Novels, and Anime. U Washington P, 2016. ix-xii.

Tacit Knowledge, Reading Practices, and Visual Rhetoric from Composition Forum 49 (Summer 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/feminist-application.php

© Copyright 2022 Aimee E. Vincent.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 49 table of contents.