Composition Forum 50, Fall 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/50/

Exploring First-Year Writing Students’ Emotional Responses Towards Multimodal Composing and Sharing Academic Work with Online Public Audiences

Abstract: This article explores the range and frequency of First-Year Writing students’ emotional responses towards a project requiring multimodal composing and distribution of their work to an online public audience prior to and after completing the assignment. I analyzed the results using Driscoll and Powell’s emotion categories (generative, disruptive, and circumstantial) and found that students experienced a variety of emotional responses towards both multimodal composing and sharing online, including anxiety, excitement, and fear. I discuss how these findings challenge some assumptions related to writing instructors’ perceptions of post-Millennial students’ comfort with and interest in multimodal composing and writing for online audiences. The article concludes by offering pedagogical suggestions for instructors interested in critically integrating this type of digital assignment.

Introduction

As a First-Year Writing (FYW) instructor at a four-year urban university with a diverse student population, I have observed, via informal first-day introductions, that students expect that they will only learn to write college-level essays addressed to the teacher. Their expectations of college writing often reflect a standard representation of an essay: paragraph-based with an emphasis on alphabetic text formatted and documented in MLA. However, students in my ENG 102 courses (the second required course in the FYW sequence) are immediately confronted with a multimodal assignment, or one that requires students to produce a text “that exceed[s] the alphabetic and may include still and moving images, animations, color, words, music and sound” (Takayoshi and Selfe 1). My students are not alone in completing this type of assignment. Many scholars in writing studies have urged instructors to integrate multimodal assignments due, in part, to their ability to motivate and engage students (Anderson; Kirchoff and Cook; Powell, Alexander, and Borton; Takayoshi and Selfe). Further empirical studies found that composing a web-based multimodal text increases students’ perceived awareness of audience due to understanding how different audiences affect rhetorical choices (Kirchoff and Cook) and using digital tools that provide the opportunity to write to an authentic audience (Nobles and Paganucci) rather than solely the teacher.

While multimodal texts may be composed as web or print based, as well as shared locally in the classroom or globally online, research has shown that sharing with an online audience motivates students (Cummings; Vetter; Vetter et al.) and helps them learn how to navigate audiences (Alexander et al.; Kirchoff and Cook; Gallagher). Responding to this research, I created a project that asked students to create a digital multimodal text that included at least two of the following elements: textual, visual, audio, and/or video and share it with an online public audience, or one that does not represent an academic audience (i.e., the teacher). In response to the assignment, students have produced websites, podcasts, videos, and/or infographics designed using various combinations of textual, aural, visual, spatial, and gestural modes to persuade a specific audience and distributed them online (often via social media platforms) to their chosen audience (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. ENG 102 Student’s Website Targeting Her Cheerleader Discourse Community

As an instructor who embraces multimodality and technology-mediated composition assignments, I assumed that students would be excited to compose a text that did not represent the standard written college essay because of my presumption that post-Millennial students (or, according to Fry and Parker, students born between 1997 and 2012) were already composing this type of work outside of the classroom. I was, for the most part, wrong. In fact, prior to the study described here, I informally observed that my students experienced a range of positive and negative emotional responses to the assignment and had various levels of experience with this type of composing. Specifically, one student’s experience illustrated the problem with my assumptions and became the basis for my fall 2019 IRB-approved dissertation study of students’ emotional responses towards multimodal composing and sharing their work with online public audiences (Gagich). Julie{1} began as a student in my ENG 101 class in fall 2017 and the next semester she enrolled in my ENG 102 class where she encountered the multimodal project. I had the opportunity to meet with her in a variety of informal settings (e.g., before and after class) where she shared that she entered the class confident in her writing skills, but the multimodal project shook her confidence. Julie explained that she was stricken with doubt about her ability to construct a multimodal text and seemed highly anxious about sharing her work with “real” audiences online.

While some students seemed to enjoy using multiple modes of communication to create a text and were excited to share their work with non-academic audiences, others shared Julie’s anxiety. This imbalance made it difficult for me and students in my course to recognize and manage the varying array of emotions triggered by the assignment and demonstrated the importance of exploring students’ emotional responses to it. It also pointed to implicit pedagogical assumptions I had about my post-Millennial students (ones that many instructors likely share): they were all excited about, prepared for, and comfortable with creating a multimodal text and sharing that work with a real audience.

Teacher assumptions. Although Marc Prensky’s term “digital native{2}” has been problematized in academic (Kirschner and De Bruykere) and popular works (Wong), vestiges of the concept of digital native seem to live in the halls (and Zoom sessions) of many English departments (e.g.,“My students do not know how to use Microsoft Word: I thought they were digital natives?” or “Of course your students like multimodal composing because they are always on social media”). Bacha’s study also recognized and questioned the assumptions many FYW instructors may make regarding students’ level of preparedness and experiences with technology necessary for creating a digital multimodal assignment. He found that while some students were “well-equipped” to handle basic digital multimodal composing assignments, when the composing task became more complex the students’ levels of preparedness significantly decreased. Research also indicates that students are frustrated by technological components associated with multimodal composition assignments requiring them to use digital technology tools (Beard).

Assumptions related to post-Millennial students’ comfort with and investment in academic projects requiring digital tools and/or multimodal composing, or those that disrupt their perception of college writing, are varied and often implicit. I created the multimodal project thinking that it would engage students but various negative emotional responses{3}, like Julie’s described above, led me to ask the following research questions:

-

How much experience do students report having with multimodal composing and sharing their work online inside and outside of academic settings?

-

What was the frequency and range of FYW students’ emotional responses prior to and after completing an assignment in my course requiring both multimodal composing and sharing that text with an online public audience?

My findings not only challenged some of the assumptions outlined here but also suggested that instructors should take students’ emotional responses into account when scaffolding their lessons.

Reviewing the Literature

Over the years, I have had the chance to discuss students’ feelings towards writing in various informal classroom contexts. Many have strong emotional reactions to writing. Some claim that they “hate” writing and dread the thought of sitting down to write, while others admit to (eventually) appreciating the writing process. These discussions demonstrate the presence emotions have in college writing classrooms and support the idea that connection(s) between the writing classroom and emotion are complex and varied. Emotional responses might be linked to the act of writing itself, extrinsic factors such as receiving a grade, and/or the content of students’ writing (Prebel); however, most likely, a combination of factors and situations affect students’ emotions in the writing classroom.

Decades of inter- and intradisciplinary research has shown that emotion affects learning (Efklides and Volet; Pekrun, Emotions and Learning; Pekrun, Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions) and requires continued study. In educational research, scholars have argued that classrooms foster intense emotional responses from both students and teachers that affect learning, performance, personal growth, and direct interactions (Pekrun, Emotions and Learning; Pekrun, Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions) making the writing classroom an excellent space to study students’ emotional responses. My study also responds to interdisciplinary arguments that it is important to study students’ emotion to understand which emotions inhibit, promote, or have no effect on learning (Efklides and Volet).

Yet, early composition research noted the problematic devaluing of student emotion in the writing classroom. For example, McLeod’s and Brand’s early work argued that the writing classroom dichotomized emotion and logic and focused on the cognitive rather than affective. However, the study of emotion in the writing classroom has grown and expanded. While some scholars have approached the study of emotion from an embodied rhetorical perspective (Micciche; Prebel) others continue to study emotion using the methods of educational psychologists (Driscoll and Powell; Driscoll and Wells). The continued exigency of the study of emotion in writing studies is also demonstrated in special journal issues such as Composition Forum’s Special Issue: Emotion and in recent research that explored students’ affective responses to disruptive assignments (Bastian).

While it might seem that emotional responses in writing classrooms might only be focused on writing, prior research has shown that students have had various emotional responses to assignments that ask them to disrupt what they conceptualize as college writing. Saidy reported on the use of a podcasting assignment created to bridge the transition between high school and college writing and offered evidence of a positive emotional response in the form of a student who believed she lacked writing skills (e.g., structure and organization) but produced a well-organized argumentative podcast. In contrast, when Bastian explored students’ affective responses to assignments that disrupted students’ traditional perception of writing and that “bring the funk” (7), she found students began the process with trepidation with the majority reporting higher comfort-levels after completing the assignment. Similarly, Beard compared students’ attitudes towards digital multimodal composing and traditional assignments and found that “a majority of students may be apprehensive about creating videos for a composition class” (149). These studies indicate the various emotional responses felt towards multimodal composing, and studying the effect of emotion continues to provide important pedagogical information related to our current (and future) learning environments.

Although some research demonstrates a variety of students’ emotional reactions to disruptive assignments, there is a gap in research explicitly studying students’ emotional responses towards an assignment that require both multimodal composing and sharing their work with real online audiences. The study described here responded to this gap in literature, and my findings offer valuable pedagogical information for instructors. In the sections that follow I review my methods, discuss results, and conclude with implications related to dispelling assumptions pertaining to post-Millennial students’ comfort levels with assignments requiring non-traditional composing methods and distribution to unfamiliar (and real) audiences. I also offer pedagogical techniques to help instructors integrate this type of assignment.

Methodology

This IRB-approved study took place in fall 2019 and was part of a larger research project that examined the effect(s) of anxiety on students’ performance on the multimodal project. The research studied the impact of a four-week emotional writing activity aimed at helping students recognize and manage their emotional responses towards the project. However, here I describe my methods for exploring students’ emotional responses.

Participants. The primary participants in this study were students enrolled in my fall 2019 semester ENG 102 course who were 18 years or older and had signed an informed consent form volunteering to participate in the study (further contextual data is reported in the “Results” section). The FYW Program Administrator distributed informed consent forms after students completed the multimodal project and kept them in her locked office. I was given access to those consent forms after final grades had been submitted and found that 79 students (approximately 86% of my students) had agreed to participate in the study. Of the students who participated in this study, 27 had taken ENG 100/101 at my university, 12 had previously taken and withdrawn from ENG 102, and 38 entered straight into ENG 102 based on their ACT/SAT score.

According to the university’s 2018 Book of Trends, in 2017 there were 12,307 undergraduate students enrolled at the institution. Within this population, 63.1% of students identified as white, 15.5% Black/African American, 7.7% non-resident alien, 5% Hispanic/Latino, 3.4% Asian, 3.1% two or more races, 2% unknown, .2% American Indian/Alaskan Native, and .1% Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander. These demographics were representative of my ENG 102 class as the majority of students were white with a smaller population of students of color and non-resident aliens (see Table 1). However, this demographic information does not provide a thorough description of each participants’ social context, individual cultures, and/or histories (Smagorinsky).

Table 1. Student Demographics

|

Demographics |

Institution |

Participants in the Study |

|---|---|---|

|

Total Undergraduate Students |

12,307 |

79 |

|

Gender |

Female (55%) Male (45% |

Female (44.3%) Male (53.2%) |

|

Age (Total students) |

18 - 24 (61%) 25 - 34 (23%) 35 - 49 (9%) Over 50 (4%) |

18 - 24 (88.6%) 25 - 34 (5.1%) 35 - 49 (1.3%) Over 50 (0%) |

|

Race |

White (63.1% ) Black/African American (15.5%) Hispanic/Latino (5%) Asian (3.4%) Two or more race (3.1%), Unknown (2%) American Indian/Alaskan Native (2% ) Native Hawaiian or Pacific Islander (.1%) Non-resident alien (7.7%) |

White (62%) Black/African American (15.2%) Hispanic/Latino(a) (3.8%) Asian (7.6%) Two or more races (5.1%) Unknown (1.3%) Other (3.8%) |

|

Language |

Not available |

Monolingual (75.9%) Bilingual (20.3%) Multilingual (2.5%) |

In the pre-survey given to the 79 students who agreed to participate, I found that 62% stated they always had access to a computer at home and 94.9% of students had access to a computer by the time they started college. Three students reported using the university’s free laptop program and one reported using it “sometimes.” When asked why they used the program two cited that it was “easier” to use a campus laptop while the other could not afford their own laptop. Further, 88.6% stated that they had Internet access at home, only 8.9% reported having access “sometimes,” and none reported never having access to the Internet (though one student did not respond and one reported “other”, which equaled 2.5%).

I also asked students to share their perceived skill level with computers because my multimodal project required students to digitally compose a multimodal text, and low perceptions of their computer skills could have influenced their feelings towards the project. Only 6.3% of students reported being “not very skilled with computers.” Though some students felt they “know the basics” (13.9%) and 1.4% stated they were an “expert with computers,” the most reported responses were “average” (39.2%) and “good computer skills” (39.2%).

Setting. The study occurred in four sections of my fall 2019 ENG 102 course. The primary goals of ENG 102 included teaching students information literacy, independent research, and argumentative writing skills. My scaffolded assignment sequence began with the multimodal project, transitioned into an Op-Ed assignment, and concluded with an academic research proposal. All four sections were held in the same classroom, which was equipped with an instructor computer at the front of the room, an overhead projector, a white board, and WiFi. Students were notified prior to the start of the semester that they were required to bring laptops or tablets to every class session. Students who did not have personal access to this hardware could rent it at the university’s facility that provided students this opportunity for free. Students could keep the laptops for 48 hours before renewing them, which allowed them to have a laptop over the course of the whole semester at home and at school; as stated above three students reported using this service for various reasons.

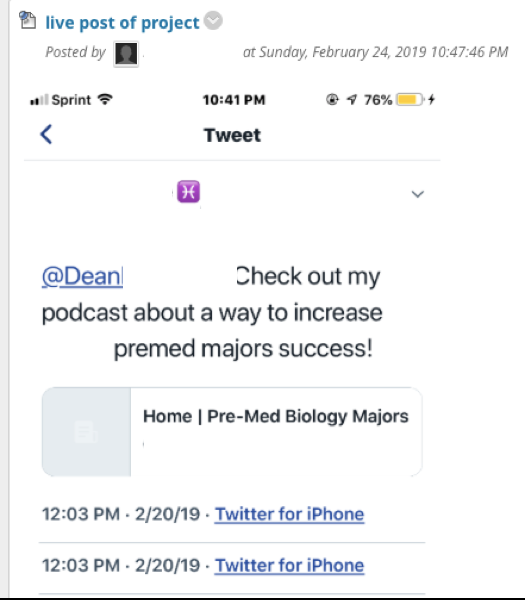

The multimodal project. The Multimodal Project (Gagich) asked students to create an argumentative multimodal text, using digital tools, addressed to a specific discourse community of which the student was a member. The final text was shared with the community by posting a link to the digital multimodal text on a site (often social media) frequented by members of that community. Students were required to show “proof” of that exchange by taking a screenshot and posting it to Blackboard for assessment (see Figure 2). The assignment directed students to create an effective text using multiple modes of communication (aural, gestural, visual, textual, and spatial), rhetorical strategies (ethos, pathos, and logos), and appropriate language shared by the discourse community. The multimodal assignment was given to students during the third week of classes. As the first assignment in the curriculum, students had not yet had an opportunity to compose formally because the first two weeks were devoted to introductory components.

Figure 2. Screenshot Showing a Student Sharing Their Podcast with Their Audience Using Twitter

Data collection. I used pre-and post-surveys to collect responses. The pre-survey included five sections: 1) open-ended questions used to determine a range of generative, disruptive, and circumstantial emotions, 2) open-ended questions pertaining to perceived influential factors, 3) modified version of the Daly-Miller Writing Apprehension Test{4} Likert-scale items to measure levels of anxiety, 4) closed-ended responses related to experience, comfort-levels, and motivation, and 5) demographic questions. The post-survey did not include the questions related to contextual factors or demographics (see Table 2). The results coded and analyzed here are students’ responses to the first survey question in both the pre-and post-survey: “Please list three emotions (use only one or two words) that best describe how you are currently feeling towards composing a multimodal text” and “feelings towards sharing your multimodal text online with real audience members” (see Appendix 1 for full pre-survey).

Table 2. Sections of the Pre- and Post-Survey

|

Survey Section |

Focus |

Survey |

|---|---|---|

|

Section 1: Open-Ended Questions |

Emotional Responses to Multimodal Composing and Perceived Influential Factors |

Pre-and Post |

|

Section 2: Open-Ended Questions |

Emotional Responses to Sharing with Real Audiences and Perceived Influential Factors |

Pre-and Post |

|

Section 3: Likert-Scale Items |

Modified Writing Apprehension Test |

Pre-and Post |

|

Section 4: Closed-Ended Questions |

Levels of Experience, Preparedness, and Motivation |

Pre |

|

Section 5: Closed-Ended Questions |

Demographics |

Pre |

The pre-survey was completed the day students were given the assignment and the post-survey was completed in class when students submitted the project.

Limitations. A key limitation in the study of emotion is the difficulty related to gathering emotion data and the improbability that researchers can study every component of emotion (Scherer). Further, using open-ended questions to collect data pertaining to students’ emotional responses had limitations, including the potential that students may not have been familiar with recognizing and naming their own emotional states (Scherer). However, my choice of open-ended questions to gather data pertaining to students’ perceived emotional states reflects Pekrun’s argument for the use of qualitative methods to aid in the formation of hypotheses and in the description of emotion phenomena (The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions).

Coding and analysis. I determined the number of units of analysis based on students’ one- to two-word answers to the survey question (which asked to list three words describing their emotion). To analyze the data, I used a deductive approach and level-one analysis. A level-one analysis requires that the researcher distinguish the object, dimensions of objects, and categories (Jansen). I first determined the object for each question prior to analyzing the data. I created a coding glossary using Driscoll and Powell’s work which informed my coding dimensions (Appendix 2). I generated a frequency word list using AntConc, a freeware language analysis tool, and then carefully hand-coded respondents’ answers by looking for categories associated with the dimensions, counting the frequency (see Table 3).

Table 3. Sample Coding

|

Object 1 |

Emotional responses prior to multimodal composing |

|

|---|---|---|

|

Dimension |

Category |

Frequency |

|

Generative Emotional Response |

Excitement |

21 |

|

Circumstantial Emotional Response |

Nervousness |

35 |

|

Disruptive Emotional Response |

Fear |

3 |

Using Driscoll and Powell as an analytical framework. Initially, Driscoll and Wells created two categories of disposition in their work studying writing transfer: generative and disruptive dispositions. Drawing from this initial research, Driscoll and Powell examined the impact emotional traits (extended emotional orientations) and emotional states (episodic emotional reactions to internal and/or external events) had on short-term assignment-based learning and long-term writing transfer and development in a longitudinal study. They defined generative, disruptive, and circumstantial emotional states to categorize their findings and I also used this categorization (Appendix 2). Driscoll and Powell defined generative emotions as those that positively affected learning, disruptive emotions as negatively affecting learning, and circumstantial emotions may positively or negatively affect learning (Table 2. Emotions, Transfer, and Writing Development).

I chose to use Driscoll and Powell’s categories because, although the focus of their research was on long-term learning and transfer, they also include data related to short-term learning providing the basis for my use of their work. This data includes words used for short-term learning, though it is important to note that while the definition of the emotional states did not change based on whether Driscoll and Powell were analyzing short-term or long-term learning, the words used to categorize results did. Thus, their work provided a framework to analyze my data using their categorization and words as I examined students’ emotional responses to a single, four-week event (i.e., the multimodal project) and those words are reflected in my analysis.

Results

In this section, I describe data related to students’ self-reported experiences with, as well as emotional responses towards, multimodal composing and sharing with an online audience prior to and after they composed their multimodal digital text.

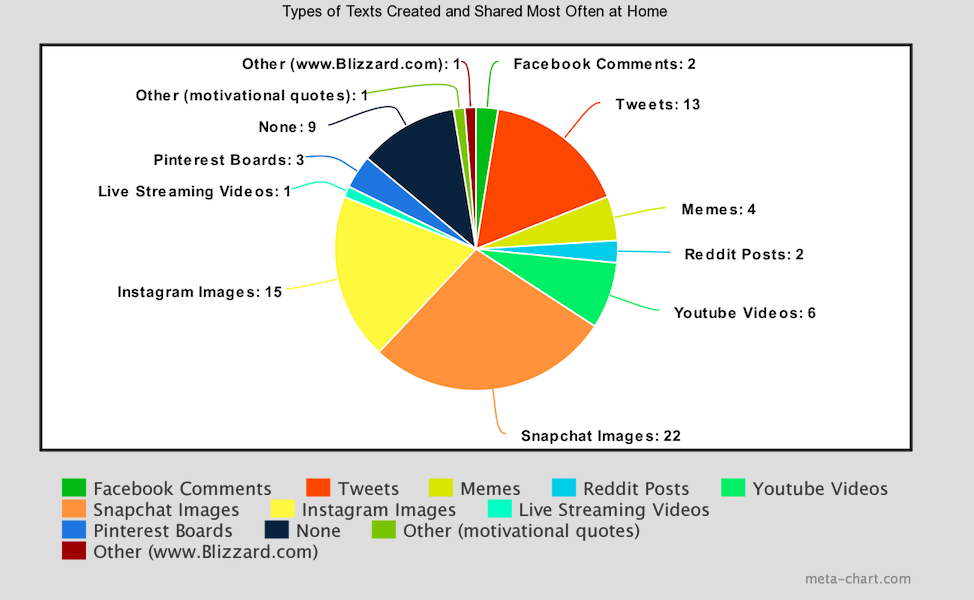

Participants’ experiences multimodal composing and sharing with online audiences. The last section of the pre-survey asked students to share data related to their experience(s) with multimodal composing and sharing texts online at home and in academic settings. I was interested in students’ experience with creating and sharing multimodal texts at home because few students indicated that they connected the social media composing they performed outside of school with the assignment that asked them to share a multimodal text with a public online audience. Figure 3 illustrates that the type of texts created and shared most often at home were Snapchat Images (22), Instagram Images (15), and Tweets (13). The next most cited response—“none”—is interesting because they were also given an “other” option in the survey, as evidenced in one student’s choice to include “www.Blizzard.com.” Though it is possible that some students did not fully understand the question, one implication is that post-Millennials may not be creating many multimodal texts as one might think or writing in online spaces—an assumption supported by Gold, Day, and Raw’s research exploring students’ online writing practices.

Figure 3. Type of Texts Created and Shared Most Often at Home

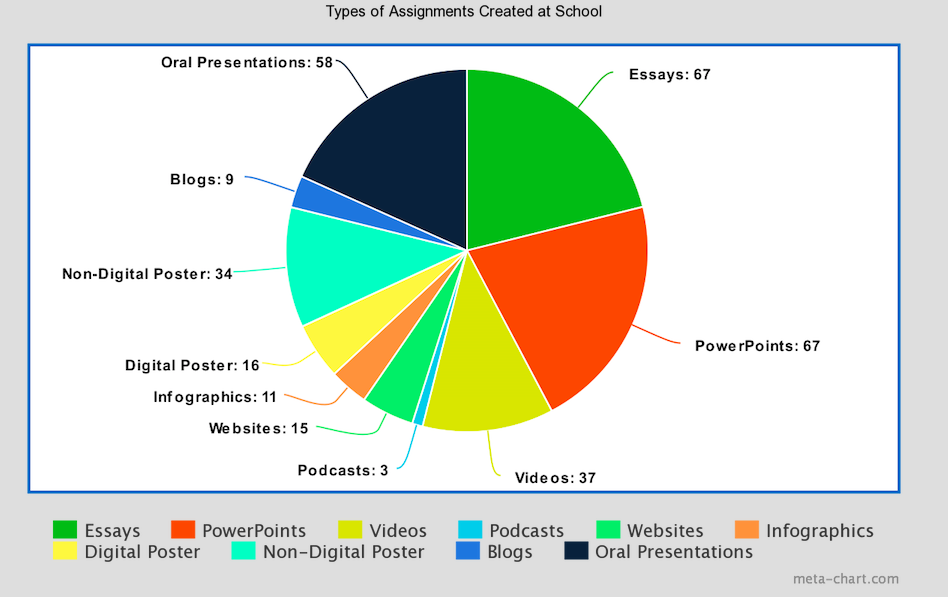

Students were also asked to share the types (as many as applicable) of assignments they composed in high school (see Figure 4). Traditional assignments such as essays (reported 67 times), PowerPoint, including other presentation freeware such as Google Slides and Prezi (67), oral presentations (58), and non-digital posters (34) were reported most often. In contrast, less traditional, digital multimodal texts (e.g., websites, podcasts, blogs, digital posters, infographics) were only reported, in a combined total, 54 times. This indicated that students had much less academic experience with composing a digital multimodal text than I originally assumed.

Figure 4. Types of Assignments Created at School

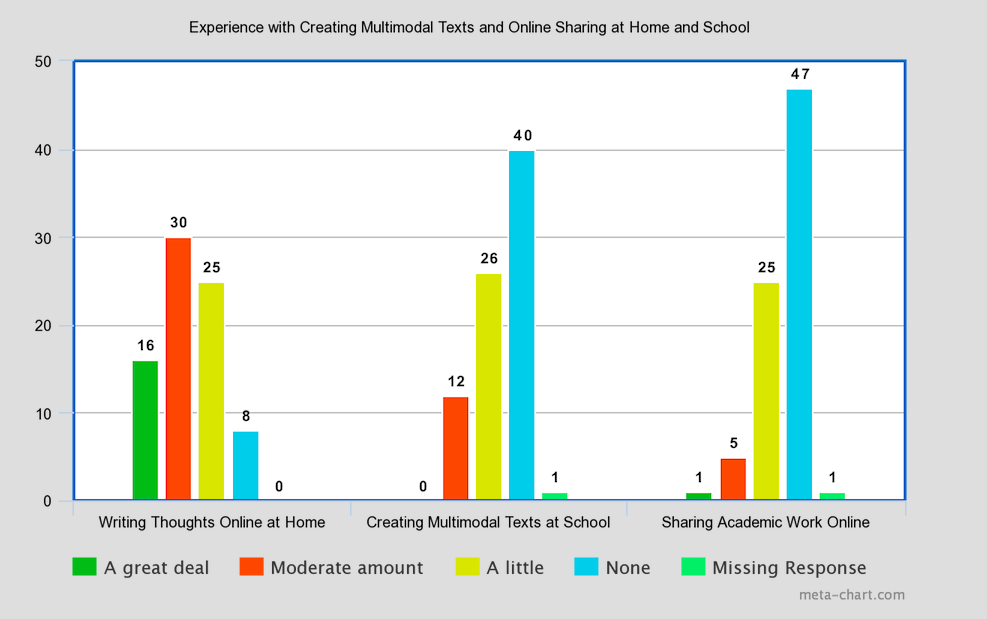

Relatedly, Figure 5 illustrates students’ perceived levels of experience with sharing writing online at home (a moderate amount), creating multimodal texts at school, and sharing academic work online. It is significant to note that 40 out of 79 students reported no experience creating multimodal texts at school, and 26 reported having a little experience. Additionally, 47 students reported having no experience with sharing an academic text online, while 25 indicated that they had a little experience. These data challenge the assumption that all post-Millennial students are consistently posting on social media.

Figure 5. Experience Creating Multimodal Texts and Online Sharing at Home and at School

Frequency of emotional responses towards multimodal composing. Here I describe data demonstrating students’ self-reported emotional responses towards multimodal composing prior to and after they composed their multimodal digital text. Table 4 represents both the pre-and post-survey responses. Student emotional responses were coded at the word level due to the survey question asking them to provide three words describing how they felt. Circumstantial emotions were the most frequently coded response related to multimodal composing prior to completing the project. Approximately 46% of students reported circumstantial emotional responses with “nervous” as the most cited emotion. “Relieved” and “relief” were the second-most cited emotion (used a total of 19 times) and categorized as circumstantial because for those students who were simply “relieved” to finish the project, then their relief likely functioned as a disruptive emotion. But for students who were able to connect their learning with the finished product, then relief likely functioned as a generative emotion.

Other, not listed, circumstantial emotional responses included those related to hesitancy such as “hesitant,” “unsure,” and “undecided.” Circumstantial emotions can affect a student positively or negatively depending on how well a student can recognize and manage it (Driscoll and Powell). If a student manages a circumstantial emotion by interacting with the assignment and composing process, then the initial emotional response is not detrimental to their short-term learning experience with the project. This is supported by the decrease in circumstantial emotions reported after completing the assignment. Circumstantial emotional responses decreased with only 24% of students reporting those feelings.

Approximately 38% of students reported experiencing generative emotional responses, or an emotional state that positively affects learning, on the day students were introduced to the assignment. The most frequently used word describing a generative emotion was “excited.” Other generative responses included words linked to positive anticipation such as “ready,” “eager,”and “anticipating success.” Driscoll and Powell argue that generative emotions can positively enhance short-term learning and the words I categorized as generative reflect emotional responses that represented excitement, happiness, motivation, and/or anticipation. Also illustrated in Table 4 are students’ post-project emotional responses towards multimodal composing. Generative emotional responses reflected the largest change with 62% (compared to 38% reported prior to completing the project) of students reporting experiencing this type of emotion. As in the pre-survey, the most cited word was “excited.” Importantly, “confident” was the next cited word with other emotional responses such as “proud,” “accomplished,” and “satisfied” also reflecting students’ confidence in their final products and/or in their accomplishment.

Lastly, 15% of students reported disruptive emotional responses prior to experiencing multimodal composing. The most used word “confusion” was not an unusual response due to the fact that students had only read the assignment once. Other disruptive emotions included “scared,” “annoyed,” “pressured,” “unprepared,” and “contempt.” Disruptive emotional responses decreased, falling from 15% prior to completing the project to just 3% after. Only one word, “scared,” was used more than once, while the others were only reported one time. This demonstrated that after completing the project, students felt less disruptive emotions towards multimodal composing. The increased generative emotional responses and decrease of circumstantial and disruptive as related to multimodal composing demonstrated that after working on the project for several weeks, students’ anxiety and/or negative perceptions of the assignment decreased. While determining the reason for this positive change was beyond the scope of this study, I would argue that student emotions linked to pride indicate that students were happy with what they produced and were excited to receive potential feedback from their audience members.

Table 4. Students' Emotional Responses to Prior to and After Multimodal Composing

|

Categories of Emotional Responses |

(Prior) Units of Emotional Responses Reported |

(Prior) Three most cited emotions |

(After) Units of Emotional Responses Reported |

(After)Three most cited emotions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Generative positively affects learning |

74/194 |

Excited (21) Intrigued (8) Interested (5) / curious (5) |

131 / 211 |

Excited (19) Confident (17) Happy (13) |

|

Circumstantial May positively or negatively affect learning |

89/194 |

Nervous (35) Anxious (16) Worried (9) |

70/ 211 |

Nervous (20) Relieved (19) Anxious (7) Stressed (7) |

|

Disruptive Negatively affects learning |

30/194 |

Confused (15) Scared (7) |

7/ 211 |

Scared (3) Used once: upset, annoyed, irritated, not super confident |

Range of emotional responses related to multimodal composing. Although circumstantial emotional responses were the most reported by students prior to completing the project, generative responses had the largest range of response with students using 28 different words. Alternatively, there were 12 words used to described circumstantial emotions and 10 for disruptive responses. Following the completion of the project, the largest range of emotional responses continued to be represented by generative emotions with 46 different emotional units reported. Alternatively, both circumstantial and disruptive emotional responses decreased in range with students reporting nine circumstantial units and five disruptive.

Frequency of emotional responses to sharing with online public audiences. This section describes students’ emotional responses towards sharing their work with real audiences prior to and after distributing it to their target audience. Table 5 summarizes the pre- and post-survey results.

40% of students reported generative emotional responses towards sharing with an online audience with “excited” being the most cited word. In the pre-survey multimodal composing emotional responses, students reported feeling “interested” and “intrigued,” which is also reflected in the post-survey audience section. Although there was an increase in generative responses (students initially reported 40% in the pre-survey with a 7% change in the post-survey), the change was not as large as the increased generative emotional responses to multimodal composing. These data show that students’ feelings towards sharing with an online audience became more generative following the completion of the project; however, that change was not as substantial as the change in feelings towards multimodal composing.

The most reported emotional response towards sharing their work with online audiences prior to completing the assignment were circumstantial, with approximately 42% reported. And, like students’ emotional responses towards multimodal composing, students were also “nervous,” “anxious,” and “worried” about sharing with online audiences. While the circumstantial emotions decreased from 42% to 40% following the completion of the project, students showed a marked decrease in circumstantial emotions towards multimodal composing compared to the 2% change in circumstantial emotions towards sharing their work online.

Further, disruptive emotional responses also decreased from the pre- to post-survey (from 16% to 7%) but the change was not as large as the change when responding to multimodal composing. Although students reported experiencing disruptive and circumstantial emotions towards both multimodal composing and sharing with online audiences before and after completing the project, they were more concerned about sharing online over the course of the entire project.

Table 5. Students’ Emotional Responses Prior to and After Sharing with a Public Online Audience

|

Categories of Emotional Responses |

(Prior) Units of Emotional Responses Reported |

(Prior) Three most cited emotions |

(After) Units of Emotional Responses Reported |

(After) Three most cited emotions |

|

Generative positively affects learning |

76 / 190 |

Excited (27) Interested (7) Curious (6) |

93/ 200 |

Excited (31) Happy (11) Curious (9) |

|

Circumstantial May positively or negatively affect learning |

79 / 190 |

Nervous (33) Anxious (15) Worried (8) |

84 / 200 |

Nervous (38) Anxious (20) Worried (5) |

|

Disruptive Negatively affects learning |

31/ 190 |

Scared (14) Confused (3) Terrified (2) |

15/ 200 |

Scared (10) Terrified (2) Embarrassed (1) |

Range of student responses to sharing with an online public audience. Similar to the range of student responses to multimodal composing, my findings revealed that students reported a broader range of generative responses (27 in total) towards sharing with an online audience. However, there was a larger range of disruptive emotional responses with 14 different words used and circumstantial emotional response with 13 various words reported compared to the pre-survey multimodal section. Post-survey results show that the range of students’ responses continued to reflect that generative emotions were the most diverse with 25 words used to describe those emotional responses. The range of circumstantial and disruptive emotional responses to continues to demonstrate less diversity in word choices with students using 14 words to describe circumstantial emotions and only four representing disruptive.

Challenging Assumptions

The results described above challenge commonly held assumptions and can help instructors make critical decisions regarding the implementation of this type of multimodal project.

Assumption 1. Post-Millennial students are excited for and comfortable with multimodal composing. One substantial result from my study was that students’ emotional responses to multimodal composing were similar to their feelings towards sharing with an online audience. Scholars have recognized that assignments asking students to share their work online might prove stressful and/or induce anxiety (Gold, Garcia, and Knutson; Gold, Day, and Raw; Santos and Leahy), so finding that students reported circumstantial emotions related to sharing their work online was not necessarily surprising. However, 45% of students reported circumstantial emotions prior to multimodal composing with only 42% reporting circumstantial emotional responses prior to sharing with an online audience. They also reported “anxiety,” “nervousness,” and “worry” for both multimodal composing and sharing with an online audience. This is meaningful because compositionists have argued for the integration of multimodal composing assignments into composition courses for the almost two decades (Takayoshi and Selfe; Yancey) with various position statements (e.g., National Council of Teachers of English and Council of Writing Program Administrators [CWPA], “WPA Outcomes”) advocating for the inclusion of multimodal assignments.

Students also reported nearly the same number of disruptive emotions (e.g., “fear” and “confusion”) prior to completing the project for both multimodal composing (15%) and sharing online (16%). While these results support research findings demonstrating that disruptive assignments caused students some apprehension prior to completion (Bastian) and that multimodal composing assignments may cause some students “concern” (Beard), they push against some disciplinary, programmatic, and localized instructor assumptions pertaining to multimodal composing assignments in FYW. The data imply that, contrary to what some compositionists might assume, students may not be comfortable with and/or excited about changing their composing practices. This finding also supports Beard’s argument that “teachers [should] not assume that a large majority of their students will automatically be interested in the prospect of creating multimodal text” (154) and should encourage instructors to think critically about why they want to integrate a multimodal assignment and if it serves as the best (or only) approach to reach course objectives.

Assumption 2. Students are willing to share anything online. Perrin and Duggan’s 2019 Pew Research Center report found that 90% of adults ages 18-24 are using social media (“Instagram, Snapchat Remain Especially Popular for those Ages 18 to 24”), showing that most students are communicating with a variety of audiences via social media. As such, there remains an assumption (one initially shared by me) that students, especially post-Millennials, want to share any digital text online, including their academic work. However, my results also showed that students do not universally share an interest in, comfort levels with, and/or willingness to participate in assignments that call for sharing their academic work online. As one student stated in response to the second open-ended survey question asking them what factors affected their emotional response, “I am more anti social [sic] towards social media and the fact that I have to share what I am doing [with] the world scares me.” Statements like this problematize popular ideas surrounding college students’ usage of social media and are supported by Gold, Day, and Raw’s argument that students “might refrain from publicly deliberating on topics of interest if they fear doing so may have negative consequences for their personal, professional, or public life…”(19).

Further, students reported a similar amount of circumstantial emotional responses towards sharing with a real audience prior to (42%) and after (40%) completing the project. Some also explained, again in response to the second survey question, that they felt nervous or worried about how their online audience would react (e.g., “I do not want to be famous on the Internet”), while others doubted their level of experience (e.g., “I’m not used to creating something for a whole community to see”). Additionally, only 7.6% of students reported “sharing texts [they] created at home” very often with the majority (41.8%) reporting that they “rarely” shared texts online at home (see Figure 4). These examples demonstrate that even if a student is already contributing and/or communicating in online participatory spaces and has experience with social media, that does not mean an assignment requiring them to share an academic text online does not cause concern. FYW instructors should not presume that our students are actively participating in online spaces as much as we might think, and we should not feel obligated to integrate these types of assignment without explicit pedagogical goals and/or reasons.

Pedagogical Implications

Outcome and position statements call for helping students understand how various rhetorical situations require different composing practices and production of texts (CWPA), learning how various technologies can be used appropriately for the distribution of information (Conference on College Composition and Communication, Principles), and that digital distribution offers opportunities for direct interaction with audiences (CWPA). Underlying these important documents is the recognition that students should learn how to navigate and compose in and for 21st century spaces. Yet, one of the most notable impacts my study has made is to unveil how varied students’ emotional responses are towards both multimodal composing and sharing with an online audience, two acts that are arguably becoming more common in writing classrooms. As I described above, this knowledge of students’ emotional responses to the multimodal project challenges implicit assumptions made by teachers, researchers, and organizations; however, it also provides meaningful pedagogical information for instructors interested in adding a digital multimodal assignment to their curriculum and/or for those who are helping students navigate digital learning landscapes during and after the COVID-19 pandemic. Below I offer pedagogical strategies that I have implemented in my classes prior to and after conducting my research as I continue to revise and reimagine the ways I integrate this type of project based on the needs of students.

Thoughtfully integrating multimodal composing assignments. Based on my findings, students are nervous to complete a task that they have not done before. While this might seem obvious, it should (re)encourage composition instructors, who wish to pursue critical implementation of a multimodal project, to help students manage their initial anxiety. I suggest using Shipka’s “multimodal task-based framework” to scaffold lessons and provide students with many examples over the course of the project. Instructors should also add an expanded introduction to multimodal composing. This should include opportunities for students to ask anonymous questions and lessons demonstrating how composing in the 21st century requires a variety of composing acts, including creating multimodal texts, navigating digital writing environments, and writing essays targeting various audiences.

Although instructors should understand that students might experience circumstantial emotional responses towards multimodal composing, it is also important to note that generative emotional responses were the most frequently cited in the post-survey regarding multimodal composing. Pedagogically, this is meaningful because students’ emotional responses towards multimodal composing changed drastically over the course of the four and a half week project. Instructors should gather information pertaining to a student’s level of engagement with, feelings towards, and their motivation for producing and designing a multimodal text using low-stake surveys. This knowledge allows the instructor to offer individualized feedback during the revision process and creates a learning space that cultivates dialogue between teacher and student. The dialogue helps an instructor recognize whether a student is simply enjoying the assignment for creativity’s sake (not necessarily a negative recognition) or if a student is making connections between the learning outcomes and the assignment.

Preparing students to share academic texts with an online public audience. Revealing students’ emotional responses towards sharing with online audiences also offers valuable pedagogical information. According to Bastian, knowing students’ perceptions of their affective responses will help instructors “be prepared for and not be discouraged or disappointed by the range of affective responses students may have as they move from what they perceive as familiar into unfamiliar genres” (27). As such, I urge instructors to make space in their curriculum for students to discuss their emotional responses to sharing with online audiences. Gold, Garcia, and Knutson offer a framework for exploring students’ reactions to writing to online audiences, including presence, persistence, permeability, promiscuity, and power. Most relevant to my findings is their discussion of “presence” or the recognition by students that online audiences are less imagined and more real with opportunities to talk back. Using this framework, teachers can guide discussions associated with fear, anxiety, and even excitement surrounding this opportunity to address a real audience.

In addition to using Gold, Garcia, and Knutson’s framework, I also suggest conducting in-class, low-stakes surveys to provide the instructor (and students) with useful information concerning how students are feeling towards sharing their work online. Open-ended and closed-ended surveys could aid instructors in determining the following: 1) a student’s emotional response towards sharing online, 2) what is affecting that response, and 3) a student’s access to technology and their technological skill levels. This knowledge could help instructors construct lessons aimed at reducing anxiety, which might include providing interdisciplinary workshops related to design, ethics, copyright, and/or privacy. This knowledge might also encourage the instructor to create and integrate low-stake digital assignments that reflect their pedagogical goals and objectives.

Navigating students’ lack of experience with technologies. To help students alleviate circumstantial and/or disruptive emotional responses related to technologies and lack of experience, instructors can determine the level of access to hardware, software, and Internet students have at the university or at home. An instructor can then make an informed decision regarding how high-tech they want the project to be. Following this decision, students can learn about technologies collaboratively by being placed in groups. This removes pressure from the teacher to be the technology expert and urges students to solve problems on an individual and group level. If an instructor is not as familiar with technology as their students or if they discover that more technology instruction is required, then this affords them an opportunity “to forge collaborations with other writing studies teacher-scholars and writing program administrators to make implementation and study of these 21stcentury writing pedagogies more mainstream” (Moore et al. 12). Those collaborations might be fostered by seeking outside assistance from colleagues or facilities such as a writing center or multiliteracy center, depending on campus resources.

Providing metacognitive activities. Giving students opportunities to think about their emotions during a project, over time, can also allow them to reconceptualize an activity that students may find stressful, for example, the multimodal project. My findings show that students are composing multimodal texts and sharing their work online (although not necessarily at the frequency I initially assumed), yet the abundance of circumstantial emotion responses at the beginning of the project suggest that students are not drawing on this knowledge. This supports Shepherd’s argument that although students might have experience with digital writing, they may not view their digital space composing as “writing” and likely compartmentalize their “home” digital and/or multimodal composing. This compartmentalization makes it difficult for students to draw upon their previous (and non-academic) experiences when asked to complete class assignments requiring multimodal composing and/or online distribution. It is also important to consider that students often struggle with technology problem-solving (Bacha), which makes it more difficult for them to navigate the technology.

Gorzelsky et al. developed “metacognitive (sub)components” that include (sub)components that sometimes (depending on the level of student criticality) represent cognition, or “thinking to complete a task,” such as “task, planning, control, and strategy” and (sub)components that represent “inherent metacognition” such as “person, monitoring, evaluation, and constructive metacognition” (226). Instructors can create and implement metacognitive activities related to helping students recognize their emotions related to multimodal composing and sharing with real audiences (e.g., “describe how you are feeling at this stage in the project”). These types of activities relate to cognition (and potentially metacognition), which can help students reach metacognitive levels by using their awareness to help them evaluate their emotion and make moves towards managing them in effective ways (e.g., “How might this feeling affect your work? What are some strategies you can use to help you move forward in your project?”).

Integrating metacognitive writing activities might also urge students to draw upon their prior knowledge and support them as they work towards developing an understanding of what it means to compose a digital multimodal text for a real and authentic audience. Further, providing metacognitive assignments related to helping students recognize and evaluate their knowledge of technologies might include offering students “technology problems” that students must “solve” and then write a reflection or journal entry explaining how they determined what the problem was, how they solved it, and what resources they used to help them. Urging students to perform this work critically can aid them in evaluating their decisions and help them understand that often a technology problem needs more time and effort than simply asking the teacher for help. While I have not yet implemented this approach in my classroom, I plan to do so in the near future.

Conclusion: Future Research

As the global pandemic continues to challenge what higher education looks like there are multiple opportunities for research related to various online and face-to-face composing and learning practices (e.g., digital and/or print multimodal projects and/or assignments requiring online distribution to larger audiences). As my study has shown, students experienced a variety of emotional responses, in the short term, to an assignment that disrupted their view of what college-writing should look like. I gathered data related to student’s emotional responses using a pre- and post-survey, but I suggest that future iterations of studies focused on studying emotion include interviews to provide a more nuanced understanding and analysis of student reflections.

While my study focused only on short-term emotional responses to a specific project, future studies could examine long-term factors and effects aligning with Driscoll and Powell’s study of the long-term impact that emotion had on writing development and transfer. Another important factor to consider is how to help students not only recognize and manage their short-term emotional responses, but to also consider how to help students to do so. In my larger study (Gagich), students were asked to write three reflective writing activities to help them keep track of and notice their emotional responses to the project. However, these activities only lasted for as long as the project (four weeks) and did not ask students to utilize all of the metacognitive (sub)components described by Gorzelsky et al. A future study could integrate semester-long reflective writing activities to trace students’ emotional changes over a longer span of time. This work might also help to answer the question related to why their generative emotional responses increased over the course of the project.

Other long-term studies could follow students over the course of their college career to find out just how much multimodal composing and/or sharing with online audiences is occurring, in what classes, and for what perceived purposes. Future studies could also explore whether there is evidence that students connect their out-of-school multimodal and digital composing with in-school assignments. Teacher-researchers could integrate practices into their classrooms, such as the reflections described above, to help students draw from their prior out-of-school experience with multimodality and/or sharing texts online with their in-school practices. Teacher-researchers could then observe the results of these practices and make claims regarding how to best foster this type of learning transfer.

While college writing classes have (as of the writing of this article) returned to traditional face-to-face spaces, the COVID-19 pandemic has illustrated the importance of helping students manage emotional responses to assignments (or learning environments) that they may find uncomfortable or unfamiliar so that they can overcome circumstantial and/or disruptive emotions. Students and teachers have been emotionally impacted by the pandemic and, arguably, we have yet to see the full outcome of this impact. As such, the work described here demonstrates not only the importance and effect of emotion on learning, but the need to continue this work in writing classrooms and beyond. Further, as mental health issues continue to rise, instructors should consider ways to help students monitor and respond their emotional responses.

The suggestions outlined here represent a piece of a larger framework for understanding multimodal composing and writing to online audiences in writing studies. The continued study of emotion in the writing classroom is essential to understanding the impact of emotion on learning and performance and how disruptions to students’ traditional perceptions of writing classrooms (e.g., moving to online spaces, writing for public online audiences, and/or compositing digital multimodal texts) might affect students emotionally. Continued study can also inform how we, as teacher-researchers, respond to student emotion in writing classrooms.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Full Pre-Survey

Block 1

The following survey asks you to respond to questions concerning the upcoming Multimodal Project.

A Multimodal Text is a text that is not a traditional essay. It is a text that includes a combination of images, sound, videos, colors, alphabetic text, etc. Some examples include websites, infographics, videos, and podcasts.

Remember, your responses to this survey will help you complete a short reflective homework assignment, but will not affect your overall grade.

Block 2

What is your first and last name?

The following questions ask you to think about composing your Multimodal Text for this project.

Please list three emotions (use only one or two words) that best describe how you are currently feeling towards composing a multimodal text.

Why do you think you feel this way? What factors do you think are influencing your feelings towards composing a multimodal text?

Block 3

The following questions ask you to think about sharing your multimodal text with real online audience members (people other than your teacher).

Please list three emotions (use only one or two words) that best describe how you are currently feeling towards sharing your multimodal text online with real audience members.

Why do you think you feel this way? What factors do you think are influencing your feelings towards sharing your multimodal text with online with real audience members?

Block 4

Please rate the degree to which you agree or disagree with each of the following statements:

|

|

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I avoid writing in online spaces (such as social media or blogs). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have no fear of my multimodal text being evaluated. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I look forward to sharing my ideas online. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I am afraid of composing a multimodal text when I know it will be evaluated. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Taking a composition course is a frightening experience. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Sharing my multimodal text will make me feel good. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

My mind seems to go blank when I start to work on a multimodal text. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Expressing ideas in a multimodal format seems like a waste of time. |

|

|

|

|

|

Please rate the degree to which you agree with the following statements:

|

|

Strongly agree |

Agree |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

I will enjoy submitting my multimodal text to online audiences. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I like to share my ideas online. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I feel confident in my ability to clearly express my ideas in a multimodal text. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I want my friends to read my multimodal text online. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I'm nervous about creating a multimodal text. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

People seem to enjoy what I write in online spaces (such as social media or blogs). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I enjoy creating online texts (such as Tweets, posts, comments, etc.). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I don't think I will be able to clearly express my ideas in a multimodal text. |

|

|

|

|

|

Please rate the degree to which you agree with the following statements:

|

|

Strongly Agree |

Agree |

Neither agree nor disagree |

Disagree |

Strongly disagree |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Creating a multimodal text seems like a lot of fun. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I expect to do poorly in composition classes even before I enter them. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I like seeing my thoughts in online spaces (such as social media or blogs). |

|

|

|

|

|

|

Discussing my multimodal text with others will be an enjoyable experience. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I have a terrible time organizing my ideas in a composition course. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

When I hand in my multimodal text, I know I will do poorly. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

It will be easy for me to create good multimodal texts. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I don't think I can create a multimodal text as well as most other people. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I don't like the idea of my multimodal text being evaluated by my teacher. |

|

|

|

|

|

|

I don't think I will be good at creating a multimodal text. |

|

|

|

|

|

Block 6

Please choose the answer that best describes you.

-

I have always had computer access at home.

-

I started having computer access at home in elementary school.

-

I started having computer access at home in middle school.

-

I started having computer access at home in college.

-

I do not have computer access at home.

-

Other (Please Specify)

Please choose the answer that best describes you.

-

I started using computers regularly before elementary school.

-

I started using computers regularly in elementary school.

-

I started using computers regularly in middle school.

-

I started using computers regularly in high school.

-

I started using computers regularly in college.

-

I do not use computers regularly.

-

Other (Please Specify)

How skilled are you with computers?

-

I am not very skilled with computers.

-

I know the basics.

-

I am average.

-

I have good computer skills.

-

I am an expert with computers.

How much experience do you have with writing your thoughts online, when you're at home or outside of school ?

-

A great deal

-

A lot

-

A moderate amount

-

A little

-

None at all

When you're at home or outside of school, how often do you post or share texts you have created online?

-

Very often

-

Often

-

Somewhat often

-

Rarely

-

Never

-

I do not understand the question.

When you're at home or outside of school, what do you create and share online most often? Choose one.

|

Facebook Comments |

Snapchat Images |

|

Tweets |

Instagram Images |

|

Memes |

Live Streaming Videos (such as Twitch) |

|

Reddit Posts |

Pinterest Boards |

|

Website Comments |

TikTok |

|

Personal Blog Posts |

Other |

|

Youtube Videos |

None |

Block 7

What, if any, types of technology did your high school provide all students with ? Choose all that apply.

|

Laptops |

e-readers (such as Kindles) |

||

|

Computer Labs |

I had no access to technology at my high school |

||

|

Tablets |

Other |

||

|

Smart Phones |

What types of assignments did you complete in high school? Choose all that apply.

|

Essays written using a word processor |

Infographics |

||

|

PowerPoints/Prezi/GoogleSlides |

Digital Posters |

||

|

Videos |

Non-Digital Posters |

||

|

Podcasts |

Blogs |

||

|

Websites |

Oral Presentations |

In high school, how often were you asked to post or share your school work online (to people other than the teacher)?

-

Very often

-

Often

-

Somewhat often

-

Rarely

-

Never

-

I do not understand the question

In high school, were you ever asked to compose a multimodal text?

-

Yes

-

No

-

I don’t know

How much experience have you had with creating multimodal texts as a school assignment?

-

A great deal

-

A lot

-

A moderate amount

-

A little

-

None at all

How much experience have you had with creating and sharing your school (or academic) work online with real audience members (not just the teacher)?

-

A great deal

-

A lot

-

A moderate amount

-

A little

-

None at all

How prepared do you feel about creating a multimodal text?

-

I feel very prepared

-

I feel somewhat prepared

-

I am not sure

-

I feel somewhat unprepared

-

I feel very unprepared

How prepared do you feel about sharing your multimodal text to real online audience members (not just the teacher)?

-

I feel very prepared

-

I feel somewhat prepared

-

I am not sure

-

I am feel somewhat unprepared

-

I feel very unprepared

On scale of 1-10 (10 being highly motivated), how would you rank your motivation to produce a multimodal text?

Please choose the answer the best describes you.

-

I am a very good writer

-

I am a good writer

-

I am an ok writer

-

I am a bad writer

-

I am a very bad writer

How do you feel about writing?

Block 8

What is your current age?

-

Under 18

-

18 - 24

-

25 - 34

-

35 - 44

-

45 - 54

-

55 - 64

-

65 - 74

-

75 - 84

-

85 or older

What is your gender?

-

Female

-

Male

-

Non-binary/third gender

-

Prefer to self-describe

-

Prefer not to say

Do you consider yourself:

-

Monolingual (I only speak one language fluently)

-

Bilingual (I speak two languages fluently)

-

Multilingual (I speak more than two languages fluently)

Please select the option that best describes your academic discipline or major.

-

Social Sciences

-

Humanities and Liberal Arts

-

Fine Arts

-

Business

-

Natural Sciences and Mathematics

-

Computer Science

-

Medical

Other (Please specify)

-

What writing course have you taken at CSU?

-

ENG 100

-

ENG 101

-

ENG 102

-

I have not taken a writing course at CSU

What high school did you attend (the name, city, and state)?

Block 9

An Anxiety Score has been calculated for you based on your responses to the Likert-Scale items.

Your Anxiety Score is:

${e://Field/Positive}

|

Low-Level of Multimodal Composing Apprehension |

Mid-Level of Multimodal Composing Apprehension |

High-Levels of Multimodal Composing Apprehension |

|---|---|---|

|

97 - 130 |

60 - 96 |

26 - 59 |

A Low-Level Score indicates that you are not apprehensive, or worried, about creating a multimodal text and/or sharing it online with real audiences.

A Mid-Level Score indicates that you are somewhat apprehensive, or worried, about creating a multimodal text and/or sharing it online with real audiences.

A High-Level Score indicates that you are apprehensive, or worried, about creating a multimodal text and/or sharing it online with real audiences. (Test and levels are modified from the Daly-Miller Writing Apprehension Test, 1975)

PLEASE WRITE YOUR ANXIETY SCORE BELOW:

Appendix 2: Coding Glossary

|

Term |

Definition |

Example |

|---|---|---|

|

Emotional response |

An emotional response is a multi-componential short-term episode in response to a triggering event (Driscoll and Powell; Scherer). The triggering events in this study is completing and sharing the project. |

“I am excited about this project” Or “I am worried about what people will think of it” |

|

Generative emotional response |

A response that could enhance the composing and learning process and “facilitate the student’s positive growth and development” (Driscoll and Powell). |

Excited, happy, confident, motivated, curious, engaged |

|

Disruptive emotional response |

These responses “can disruptive and interfere” with a student’s composing and learning processes (Driscoll and Powell). |

Scared, angry, bored, ambivalent, fearful |

|

Circumstantial emotional response |

These responses are emotional states that “could be either generative or disruptive in the short and long term” (Driscoll and Powell) |

Anxious, nervous, worried, frustrated, confused |

Notes

-

Students names have been changed. (Return to text.)

-

Prensky defines “digital native” as students who are all “‘native speakers’ of the digital language of computers, video games, and the Internet” (1). (Return to text.)

-

My use of the term “emotional response” echoes Scherer’s and Driscoll and Powell’s definitions of emotional state. I am not studying students’ long-term dispositions, nor am I exploring their personality or intellectual traits. An “emotional response” in this text refers to a multi-componential short-term emotional state. (Return to text.)

-

The original Daly-Miller WAT included 26 Likert-scale items asking students to respond to a five-point rating scale. The items reflected general writing anxiety, peer evaluation of writing, teacher evaluation of writing, and professional (or non-classroom) evaluation of writing (Daly and Miller 245). (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Alexander, Kara Poe, Beth Powell, and Sonya C. Green. Understanding Modal Affordances: Student Perceptions of Potentials and Limitations in Multimodal Composition. Basic Writing e-Journal, vol. 10, no. 11, 2012, https://bwe.ccny.cuny.edu/alexandermodalaffordances.html.

Anderson, Daniel. The Low Bridge to High Benefits: Entry-level Multimedia, Literacies, and Motivation. Computers and Composition, vol. 25, no.1, 2008, pp. 40-60, doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2007.09.006.

Bacha, Jeffery A. Technological Familiarity & Multimodality: A Localized and Contextualized Model of Assessment. Computers and Composition Online, 2017, https://cconlinejournal.org/bacha/.

Bastian, Heather. Student Affective Responses to ‘Bring the Funk’ in the First-Year Writing Classroom. College Composition and Communication, vol. 69, no.1, 2017, pp.6-34, https://www.ncte.org/library/NCTEFiles/Resources/Journals/CCC/0691_sept2017/CCC0691Student.pdf.

Beard, Jeannie C. Parker. Composing on the Screen: Student Perceptions of Traditional and Multimodal Composition. 2012. Georgia State University, PhD dissertation. ScholarWorks@GeorgiaStateUniversity, https://scholarworks.gsu.edu/english_diss/98/.

Brand, Alice G. Hot Cognition: Emotions and Writing Behavior. Journal of Advanced Composition, vol. 6, 1985, pp. 5-15.

Cummings, Robert E. Are we Ready to use Wikipedia to Teach Writing? Inside Higher Ed, 12 Mar. 2009, https://www.insidehighered.com/views/2009/03/12/are-we-ready-use-wikipedia-teach-writing.

Daly, John A., and Michael D. Miller. The Empirical Development of an Instrument to Measure Writing Apprehension. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 9, no. 3, 1975, pp. 242-249, https://www.jstor.org/stable/40170632.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 26, 2012, https://compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Roger Powell. States, Traits, and Dispositions: The Impact of Emotion on Writing Development and Writing Transfer Across College Courses and Beyond. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.com/issue/34/states-traits.php.

Efklides, Anastasia, and Simone Volet. Emotional Experiences During Learning: Multiple, Situated, and Dynamic. Learning and Instruction, vol. 15, no. 5, 2005, pp. 377-380, doi:10.1016/j.learninstruc.2005.07.006.

Fry, Richard, and Kim Parker. Early Benchmarks Show ‘Post-Millennials’ on Track to be Most Diverse, Best-Educated Generation Yet. Pew Research Center, 15 Nov. 2018, https://www.pewsocialtrends.org/2018/11/15/early-benchmarks-show-post-millennials-on-track-to-be-most-diverse-best-educated-generation-yet/.

Gagich, Melanie E. Examining First-Year Writing Students’ Emotional Responses Towards Multimodal Composing and Online Audiences. 2020. Indiana University of Pennsylvania, PhD Dissertation. ProQuest, https://www.proquest.com/openview/254d9acf232249f0c61fe252926e4ca8/1?pq-origsite=gscholar&cbl=18750&diss=y.

Gallagher, John R. Considering the Comments: Theorizing Online Audiences as Emergent Processes. Computers and Composition, vol.48, 2018, pp. 34-48, doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2018.03.002.

Gold, David, Jathan Day, and Adrienne E. Raw. Who’s Afraid of Facebook? A Survey of Students’ Online Writing Practices. College Composition and Communication, vol. 72, no.1, 2020, pp. 4-30.

Gold, David, Merideth Garcia, and Anna V. Knutson. Going Public in an Age of Digital Anxiety: How Students Negotiate the Topoi of Online Writing Environments. Composition Forum, vol. 41, 2019, https://compositionforum.com/issue/41/going-public.php.

Gorzelsky, Gwen, et al. Cultivating Constructive Metacognition: A New Taxonomy for Writing Studies. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, WAC Clearing House, 2016, pp. 215-246. doi:10.37514/PER-B.2016.0797.2.08.

Jansen, Harrie. The Logic of Qualitative Survey Research and its Position in the Field of Social Research Methods. Forum: Qualitative Social Research, vol. 11, no. 2, 2010, https://www.qualitative-research.net/index.php/fqs/article/view/1450.

Kirchoff, Jeffery S. J., and Mike P. Cook. The Impact of Multimodal Composition on First Year Students’ Writing. Journal of College Literacy and Learning, vol. 42, 2016, pp. 20-39.

Kirschner, Paul A. and Pedro De Bruyckere.The Myths of the Digital Native and Multitasker. Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 67, 2017, pp. 135-142, doi: 10.1016/j.tate.2017.06.001.

McLeod, Susan H. The Affective Domain and the Writing Process: Working Definitions. Journal of Advanced Composition, vol. 11, no. 1, 1991, pp. 95-105.

Micciche, Laura R. Doing emotion: Rhetoric, writing, teaching. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 2007.

Moore, Jessie L., et al. Revisualizing Composition: How First-Year Writers Use Composing Technologies. Computers and Composition, vol. 39, 2016, pp. 1-13. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2015.11.001.

Nobles, Susanne, and Laura Paganucci.Do Digital Writing Tools Deliver? Student Perceptions of Writing Quality Using Digital Tools and Online Writing Environments. Computers and Composition, vol.38, Part A, 2015, pp.16-31, doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2015.09.001.

Pekrun, Reinhard. Emotions and Learning. E-book, International Academy of Education, 2014.

Pekrun, Reinhard. The Control-Value Theory of Achievement Emotions: Assumptions, Corollaries, and Implications for Educational Research and Practice. Education Psychology Review, vol.18, 2006, pp. 315-341. doi:10.1007/s10648-006-9029-9.

Perrin, Andrew, and Maeve Duggan. American’s Internet Access: 2000-2015. PEW Research Center, 26 June 2015, https://www.pewresearch.org/internet/2015/06/26/americans-internet-access-2000-2015/.

Powell, Beth, Kara Poe Alexander, and Sonya Borton. Interaction of Author, Audience, and Purpose in Multimodal Texts: Students’ Discovery of Their Role as Composer. Kairos: Rhetoric, Technology, and Pedagogy, vol.15, no. 2, 2014, https://praxis.technorhetoric.net/tiki-index.php?page=Student_Composers.

Prebel, Julie. Engaging in a ‘Pedagogy of Discomfort’: Emotion as Critical Inquiry in Community-Based Writing Courses. Composition Forum, vol. 34, 2016, https://compositionforum.com/issue/34/discomfort.php.

Prensky, Marc. Digital Natives, Digital Immigrants. On the Horizon, vol.9, no. 5, 2001, pp. 1-9, doi:10.1108/10748120110424816.

Principles for Postsecondary Teaching of Writing. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 2015, https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/postsecondarywriting.

Saidy, Christina. Beyond Words on the Page: Using Multimodal Composing to Aid in the Transition to First-Year Writing. Teaching English in the Two Year College, vol. 45, no. 3, 2018, pp. 256-273, https://search.proquest.com/docview/2057945567?pq-origsite=gscholar.

Santos, Marc C. and Mark H. Leahy. Postpedagogy and Web writing. Computers and Composition, vol. 32, 2014, pp. 84-95. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2014.04.006.

Scherer, Klaus R. Psychological Models of Emotion. The Neuropsychology of Emotion, edited by Joan C. Borod, E-book, Oxford University Press, 2000, pp. 137-162.

Shipka, Jody. A Multimodal Task-Based Framework for Composing. College Composition and Communication, vol. 57, no. 2, 2005, pp. 277 - 306.

Shepherd, Ryan P. Digital Writing, Multimodality, and Learning Transfer: Crafting Connections between Composition and Online Composing. Computers and Composition, vol. 48, 2018, pp. 103-114. doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2018.03.001.

Smagorinsky, Peter. The Method Section as the Conceptual Epicenter in Constructing Social Science Research Reports. Written Communication, vol. 25, no. 3, 2008, pp. 389-411, doi:10.1177/0741088308317815.

Takayoshi, Pamela, and Cynthia L. Selfe. Thinking About Multimodality. Multimodal Composition: Resources for Teachers, edited by Cynthia L. Selfe, Hampton Press, 2007, pp. 1-12.

Vetter, Matthew. Archive 2.0: What Composition Students and Academic Libraries can Gain from Digital-Collaborative Pedagogies. Composition Studies, vol. 42, no. 1, 2014, pp. 35-53.