Composition Forum 52, Fall 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/

Engaging Graduate Instructors in Composition Theory through Reflective Writing

Abstract: Research on writing pedagogy education (WPE) emphasizes the importance of engaging graduate student instructors (GSIs) in mindful reflection about their own practices and about composition theory. Little research, however, has explored what we learn from a systematic, empirical investigation of GSIs’ reflective writing. In this article, we describe a writing assignment we created for a graduate composition theory course that required GSIs to connect their own beliefs and experiences with the theory they read. We analyzed 60 essays to learn how new writing teachers understand and use composition theory. Our analysis shows that GSIs rely on three discursive patterns to write about theory (we call these cite-comment, cite-apply, cite-engage) and adopt three orientations towards theory (using theory to explain prior beliefs and maintain a teacherly identity, to solve classroom problems and shore up a teacherly identity, and to accept uncertainty and become a reflective teacher). We discuss connections between GSIs’ discursive strategies and their theoretical orientations. We conclude by sharing how we have revised both this assignment and our training program to help GSIs better engage theory as they reflect on their own experiences. Finally, we explore the implications of what we learned for WPE broadly.

Introduction

As writing program administrators, we find writing pedagogy education—preparing new graduate student instructors (GSIs) to teach—one of the most challenging and rewarding things we do. We are always looking for better ways to help GSIs “teach, reflect, innovate, and theorize about the practice of teaching writing in college” (Estrem and Reid, Writing Pedagogy Education 224). Research has emphasized the value of reflection for writing program education (WPE) and shows that many writing pedagogy educators now see reflection as a core element of their curriculum (Brewer; Cicchino; Dryer; Estrem and Reid, What New Writing Teachers Talk About; Reid, Teaching Writing Teachers Writing). As such, the practice of reflective writing may represent what John Raucci calls a “cherished belief” that is worth “challenging, verifying, refining, and extending” (449). While we agree that reflection activities benefit GSIs, we suggest there is more to learn from the results of these activities: GSIs’ written reflections. These reflections provide valuable data about how GSIs understand and theorize teaching—and, by extension, how well our reflection assignments are working to help GSIs become effective teachers. This article reports on a systematic study of the reflective writing GSIs produced in our WPE seminars, what those reflections taught us about supporting GSIs’ development as teachers, and how that knowledge can inform WPE.

At our university, where all GSIs are master’s students, we’ve long used a three-pronged approach to teacher preparation: a week-long summer boot camp, a pedagogy seminar taken during GSIs’ first semester of teaching, and weekly colloquium meetings held throughout GSIs’ two years in our program. These are our only requirements for teaching, but we encourage GSIs to participate in additional professional development opportunities on campus and at conferences. We believed that our three prongs provided a useful balance of theoretical and practical knowledge and intellectual and emotional support. However, Amy, who teaches the composition pedagogy seminar, noticed a consistent pattern on end-of-semester student evaluations: students complained that the seminar was too theoretical at a time when they needed concrete and pragmatic advice about what to do in class. Feeling a keen pedagogical imperative, some GSIs viewed the seminar as being on the wrong side of the theory/practice divide (see Dobrin; Ebest; North; Stancliff and Goggin; Worsham).

We wanted to respond to students’ concerns while still helping them “teach, reflect, innovate, and theorize” (Estrem and Reid, Writing Pedagogy Education 224, emphasis added). So, beginning in the fall of 2020, we added a series of “Teaching and Learning Reflection” (TLR) assignments to our seminar curriculum. Inspired by Shelley Reid’s inquiry-based WPE (Uncoverage), these TLR assignments ask students to connect the research and theories they read to their prior experiences as writing students and their new experiences as teachers. We believed these TLR assignments would help GSIs accomplish the seminar’s stated learning outcomes which are (1) to identify key concepts, issues, and questions in composition theory and pedagogy; (2) to critically examine theories about learning and teaching writing; and (3) to reflect on their teaching. More importantly for our research, these reflection assignments provide us access to “students’ own voices, and close to the moment of the experience” (Jankens and Latawiec). In these essays, GSIs use composition research and theory to validate, problem-solve, question, and mindfully explore their teaching practices. With increased understanding of how our GSIs use the field’s scholarship and how they respond to reflective writing assignments, we are able to adjust our curriculum and pedagogy to better support their developing competence as teachers.

Our study analyzed 60 TLR assignments from 20 first-semester master’s students to understand how GSIs reflectively connect theory and classroom experiences. We follow Sanchez and Fischer in defining theory as “generalized accounts of what writing is and how it works” (Sanchez 1) or ways to make sense of pedagogical practice (Fischer 204). Pedagogy is how teachers put theory, research, and personal beliefs to work—the “related practices that emerge” from their accumulated teaching knowledge (Tate et al. 3). We considered most of the seminar’s assigned readings—about rhetoric, expressivist pedagogy, process pedagogy, cultural critical pedagogies, etc.—to be theory (see Appendix A). As we examined the TLR assignments, we found that GSIs used different discursive patterns to write about theory and adopted different teaching orientations toward theory. Below, we explain each of these discursive patterns and theoretical orientations and discuss relationships between them. In general, GSIs initially used theory to reinforce and maintain their existing beliefs about teaching and comment on theory. But throughout the semester, most GSIs at times exhibited uncertain and nuanced thinking about the relationship between theory and their teaching experiences. We hypothesize that despite the uncertainty GSIs express in these moments, their writing reflects increasing confidence in reading, applying, and questioning theoretical texts. In these moments, theory also seems to become more valuable to GSIs because it helps them recognize and begin to address the complexity of teaching. We learned our prompts and teaching could do more to encourage this kind of uncertain reflection, in which GSIs are comfortable questioning theoretical texts and their own teaching practices. The results of this study may help writing program administrators (WPAs) guide GSIs to navigate the theory-practice divide through reflection.

Assignment Rationale

Our TLR assignments ask GSIs to critically explore their experiences by reflecting on prior experiences as writing students and current experiences as writing teachers, to articulate beliefs they hold about teaching and learning writing that were shaped by those experiences, and to intentionally integrate their experiences and beliefs with concepts and theories from composition research (see Appendix B; the same prompt was used for all three TLR assignments). Students complete the TLR assignments during the first half of the semester. In this way, our TLR assignments respond to both our own students’ complaints about the seeming irrelevance of composition theory for classroom practice and to larger field-wide tensions about balancing theory and practice in GSI preparation (see Dobrin; Stenberg and Lee; Reid et al.).

In asking GSIs to write about their own teaching experiences, we build on a longstanding tradition: Reid notes that “one of the few widely-agreed-upon elements of writing teacher education is that writing teachers should be asked to write as part of their professional development” (Teaching Writing Teachers Writing 197). As early as the 1910s, Harvard University’s teacher preparation program required graduate students to write regularly, allowing them to better empathize with their first-year writing students (Pytlik 7). The field at large now encourages metacognitive reflection and writing about theory and practice as key elements of teacher preparation (Reid, Teaching Writing Teachers Writing; Bauer et al.).

Writing studies scholars seem to agree that instructors need a solid foundation in composition theory (CCCC Statement on Preparing Teachers of College Writing; Hansen; Stancliff and Goggin). Hesse suggests that this foundation distinguishes a professional teacher from a writing enthusiast. Still, some scholars, like us, have noted the challenge of engaging new GSIs in theoretical ideas when they are occupied by more urgent concerns about managing practical, day-to-day classroom work. Perhaps this is why many WPE programs maintain a “primarily skills-based approach” (Latterell 22) to teacher preparation and why the question of GSI “resistance” to theory regularly crops up in the professional literature (see Ebest; Grouling; Hesse; Stancliff and Goggin; Stenberg and Lee; Welch). Amy Cicchino’s 2020 survey of 38 WPE programs suggests that the limited timeframe for teacher preparation (usually confined to the first year or even just the first semester of teaching) means preparation ends just as GSIs are “getting acclimated to theoretical knowledge” (98). This prevents them from seeing “how their teaching should be connected to theoretical knowledge” (98). Jessica Restaino notes GSIs may struggle integrating composition theory into their practice in part because of the divide “[b]etween those who theorize the field and those who do most of the classroom teaching” (95). While GSIs need practical preparation, a strongly skills-based approach may look like “managing” GSIs rather than preparing them for mindful, agentive teaching (Taylor and Holberg).

Composition scholars have noted the importance of combining theory and written reflection. Catherine Latterell suggests that reflecting on theory prepares GSIs for unpredictable future concerns (20-21). In her letter to new teachers, Reid writes that metacognitive reflection—“the stories you tell yourself about teaching and being a teacher, how you accustom your neurons to solving teaching problems”—helps GSIs thrive as teacher-learners even after their composition theory courses have ended (On Learning 135). She claims that GSIs who evaluate their prior and existing knowledge increase their “tolerance for productive uncertainty” and are better positioned to combat imposter syndrome, build community with other instructors, align their pedagogy with their beliefs, and recognize the limits of their prior knowledge (137). Reflection helps GSIs recognize both their competence and incompetence, allowing them to build on the former and address the latter.

Reflection may also help GSIs see how theory and teaching intersect. Shari Stenberg and Amy Lee resist the idea of a “one-way relationship” from theory to practice, calling instead for a “dialectical relationship” between the two (331). Our TLR assignments ask students to make the dialectical relationship explicit by describing events that make up their writing/teaching/learning pasts and consciously exploring the beliefs and theories they hold because of these experiences. Further, the assignments require students to identify principles and concepts from writing studies literature that speak to what they have known, done, and felt as writers, students, and teachers. This back-and-forth metacognitive movement allows them time to do the “mucking around—reading and writing as if things made sense” that Doug Hesse advocates when he argues GSIs should engage critically “with provocative theoretical texts” because “reflecting on one’s experiences [alone] is not itself sufficient” to help GSIs develop their reflective capacities (228).

Reflection can also help GSIs articulate, critically evaluate and mindfully enlarge their tacit knowledge and expertise. GSIs, especially those in English departments, already possess significant writing knowledge and proficiency. If they have always excelled at writing, they may view it as a “taken-for-granted practice” (Fedukovich and Hall). Similarly, the decade-plus GSIs have spent in writing classrooms as students qualifies them as “writing/teaching theorist(s)” (Reid, On Learning 130). Still, GSIs may struggle to transfer their embodied, experiential knowledge and expertise to their classroom teaching (Rice; Rupiper Taggart and Lowry; Qualley). This struggle can destabilize new instructors. Elizabeth Saur and Jason Palmeri’s addendum to Reid’s letter emphasizes that teaching is “messy, emotional work” (146) and that GSIs’ “embodied positionalities (including race, class, gender, sexuality, disability, and age) strongly influence” their teaching (150). Drawing on the work of these scholars, we designed our TLR assignments to ease GSIs into this messy work.

Reflectively combining prior experiences with published theory is important because research by Reid et al. shows that prior knowledge is the foundation of GSI confidence and that new instructors are more likely to draw on prior knowledge than the new knowledge they acquire from WPE, even if that prior knowledge is inappropriate or ineffective. Indeed, they write that GSIs’ exposure to theory through WPE “occupies a limited and sometimes peripheral position in their daily thoughts and practices regarding teaching writing” (49). Additional research on how GSIs’ experiences and proto-theories influence their practices reinforce these findings. Meaghan Brewer’s research found GSIs’ conceptions of what literacy means stems in part from their prior disciplinary training and influences what they value and emphasize in their own teaching practices. Similarly, Meridith’s previous research found that GSIs’ disciplinary allegiances and backgrounds influence how they receive teacher preparation, that GSIs studying in fields outside of writing studies typically see less value in reading composition theory to help them gain confidence or skill in teaching, and that all GSIs (no matter their disciplinary emphasis) tend to value their own experiences above reading theory to aid their teaching (Reed). In response to these findings, we believe assignments like TLRs can help GSIs mindfully reflect on ideas they bring with them and use the field’s theories to elaborate and refine their personal theories.

Research Site and Methods

With IRB approval, we analyzed TLR assignments from 20 first-year graduate students at Brigham Young University, a private, religious institution located in Provo, Utah, during Fall Semester 2020. We offer two sections of composition pedagogy each fall; both sections use the same syllabus. All new GSIs are required to take this seminar during their first semester of teaching. Students start the semester reading Tate et al.’s Guide to Composition Pedagogies with supplemental texts chosen from our field’s journals. During the second half of the semester, we read Brian Jackson’s Teaching Mindful Writers and additional supplemental readings. Again, students complete the TLR assignments during the first half of the semester, spaced about three weeks apart and while they are reading the Guide and associated readings (see Appendix A for readings and schedule). These readings form the basis of seminar discussions, during which faculty try to model connecting theory to teaching practice. For example, as we read about process theory, we identify elements of our required textbook for First-Year Writing (FYW) that are informed by process theorists. Similarly, we discuss which theories of genre shape the major required assignments in our FYW course and how other ways of approaching genre might benefit our students. We critically evaluate the theories we read, inviting GSIs to consider, for example, the advantages and possible drawbacks of emphasizing writing process with their specific students. The goal of these classroom conversations is to help GSIs see that teachers, textbook authors, and WPAs use theory critically to make curricular choices for FYW. Faculty also give written feedback on each TLR assignment that, combined with seminar discussions, undoubtedly influences the essays.

The seminars are taught by our university’s WPAs, including Amy. Eleven of the participants in this research were students in her seminar section. The remaining nine were enrolled in the section taught by our university’s other WPA, a tenured professor. Three male students and seventeen female students shared their essays with us. Male students make up only 15% of our sample, but this percentage roughly matches the percentage of male students in the full cohort of 24 students (16.6%). All research participants are White and most were in their 20s, which is a limitation to our study (see Appendix C). Future research would benefit from more diverse participants. Many of our GSIs have prior, albeit limited, teaching experience as undergraduate TAs or writing center tutors. Some have professional teaching experience as well. Because we are a religious institution, many of our students list church teaching experiences on their resumes when they apply for a GSI position. In class discussions, however, Amy found that students rarely referenced teaching in church settings, instead foregrounding their prior TA, tutoring, and professional teaching in secondary or college settings.

Initially both researchers read and annotated each TLR paper. Collaboratively, we wrote summaries of our initial impressions about how students put theory in conversation with their classroom experiences as students and teachers. These “character sketches,” as we called them, functioned in much the same way an initial round of open coding might. We looked at how students approached theory: their ability to articulate a theory, their attitude about theory’s value, their perception of theory’s relationship to pedagogical practices (their own and their seminar instructors’), and their sense of theory’s relevance for their day-to-day teaching. We centered our analysis on GSIs’ writing about theory because we hoped to provide insight into the tension, noted above, that many GSIs feel between theory and practice during their teacher preparation. We noticed that students seemed to use a handful of discursive strategies when incorporating theory into their writing. We also saw trends in how GSIs used theory to orient themselves to teaching and a teacherly identity. These apparent patterns of discursive strategies and teaching orientations became the focus of our analysis.

Having established textual features and teaching orientations as our conceptual interests, we used MAXQDA software to segment and code each TLR essay. We segmented the text around any reference to theory, which we defined as naming a scholar or a theoretical concept, describing a theory, referencing a particular course reading, or summarizing an idea or concept from one of the readings. All text associated with that reference became part of the segment, resulting in segment lengths that varied from a sentence to several paragraphs. A segment ended (and a new segment began) when the writer introduced a new idea, name, theory, concept, or quote. We then looked at these segments to discover the discursive strategy students used to talk about theory, ultimately identifying four distinct discursive patterns that accounted for every use of theory. In our findings, we discuss three of these patterns. In the fourth pattern, which we called meta-discourse, students mentioned a theory in a phrase or clause about the structure of the paper itself, such as in a transition. We do not include instances of meta-discourse in our findings. We assigned one, and only one, discursive pattern code to each segment. We then coded each segment for how students oriented themselves toward the theory, meaning what use they made of the theory relative to their teaching identity (see Appendix D for codebook). We noted three orientations—maintaining a teacherly identity, shoring up a teacherly identity, and becoming a teacher. Our coding rules allowed double coding for orientations, but we found that we never needed to code a segment with more than one orientation. Some segments did not express an orientation and thus were not coded. Analysis of our coded data allowed us to see the relationships between students’ discursive patterns and theoretical orientations that we discuss below.

We note that Amy’s abundant and varied interactions with study participants may have affected her interpretation of the texts. In addition to teaching the seminar, she had observed students’ teaching, occasionally helped resolve complaints from their students, and been a member of two participants’ thesis committees. To account for this, we coded all TLR essays together and, at every stage of the analysis process, discussed and compared our interpretations. We reached agreement on what counted as a segment and the codes we applied to a segment “through collaborative discussion rather than independent corroboration” (Smagorinsky 401). We also see Amy’s familiarity with the participants as a way to triangulate our findings. In our research meetings we sometimes discussed what she knew about her students to help us understand what we saw in their texts; likewise, we considered what we saw in the texts to help us better understand these students.

We acknowledge other limits to our data collection and analysis. We’ve noted above the possible influence of seminar instruction and faculty’s feedback on the data. Additionally, our data comes from an assignment we designed for a particular purpose; consequently, we had to be careful that we were not looking for the assignment’s “success.” This reflexivity was especially important since, as Hardy et al. note, graded reflection assignments are always troublesome research instruments, and students may simply reflect what they think the instructor wants to hear or offer evidence of “highly contextual” moments, not their orientation “writ large.” For example, the GSIs in our study may be trying to tell us what they think we want to hear and may not understand the prompt as inviting critical engagement with theory or critical assessment of their teaching. Furthermore, the assignment itself is only “one piece of the complex context of instruction in any course.” Like Hardy et al., we believe our research would be strengthened by observing the seminar classes, analyzing feedback GSIs receive on their TLR assignments, or conducting discourse-based interviews about GSIs’ intentions behind their use of theory.

Findings

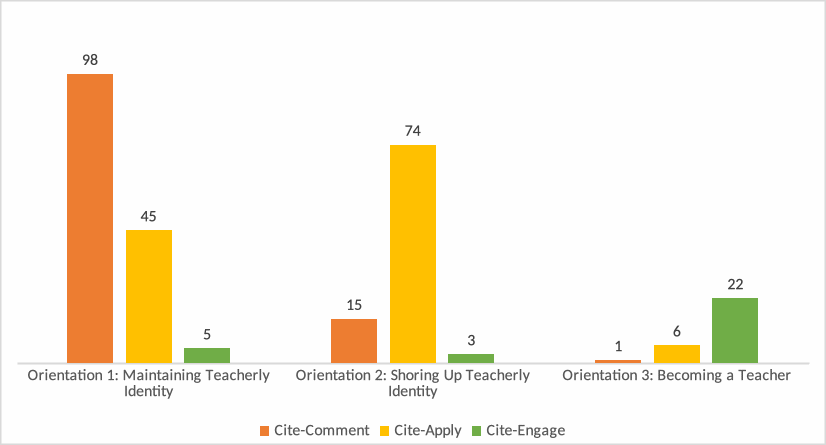

We identified three orientations to theory in the sixty TLR essays: students used theory to explain existing beliefs about teaching and maintain a teacherly identity, to solve teaching problems and shore up their teacherly identity, and to explore and accept uncertainty and become reflective teachers (see fig. 1). Not every GSI adopted each orientation, nor was there a clear pattern of movement between orientations. Still, while orientation 1 (maintaining teacherly identity) dominated the first essay, orientations 2 (shoring up teacherly identity) and 3 (becoming a teacher) became more prominent by the third essay. This progression suggests that as GSIs continually reflect on theory, they may see additional uses for theory in their teaching practice.

Figure 1. Relationship of Discursive Patterns & Orientations to Teacherly Identity. Number of coded segments of each discursive pattern associated with an orientation across all 60 TLR essays. All 20 GSIs used orientations 1 & 2 while 10 GSIs used orientation 3.

GSIs used distinct discursive strategies to integrate theory into their papers. We call these strategies cite-comment (theory cited with minimal commentary), cite-apply (theory cited with direct application to a classroom problem or challenge), and cite-engage (theory summarized and synthesized with other theories, personal analysis and> questioning, or reflection on and interrogation of pedagogy and theory). We see some parallels between these discursive patterns and Reid’s discussion of GSIs’ need for declarative, procedural, and metacognitive knowledge (On Learning), since cite-comment shows GSIs quoting or restating declarative ideas from composition theory, cite-apply involves looking for procedural applications of theory, and cite-engage looks like metacognitive self-analysis of GSIs’ practices and beliefs as teachers. As we discuss below, these strategies often correlate with students’ orientations to theory: shifts in students’ discursive patterns seem to mirror shifts in their use of and engagement with theory (see Figutre 1). Thus, discursive patterns may alert WPAs to how GSIs orient their learning and experiences with theory.

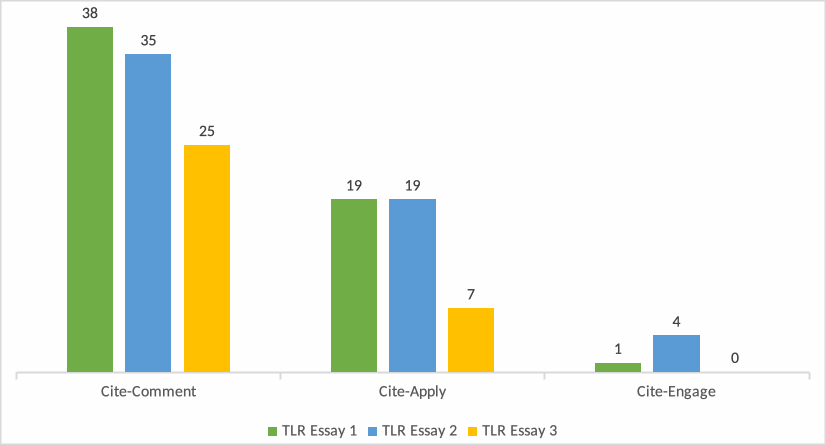

Orientation 1: Maintaining a Teacherly Identity by Aligning Theory with Prior Experiences and Existing Beliefs

Across all sixty TLR essays, 55% of the coded segments show GSIs’ maintaining and asserting an identity based on their existing beliefs or prior experiences as teachers and students (see Figure 1). Although these are new teachers, we use the word maintaining to indicate the power of their past on their present sense of themselves as teachers. This orientation appears most frequently in the first TLR essay and becomes less prominent in the second and third TLR essays. As Figure 2 shows, GSIs are most likely to use the cite-comment pattern when expressing this orientation, in which they use theory to support established attitudes about teaching writing or explain existing interpretations of prior experiences. In mutually constitutive fashion, students also use their prior experience and beliefs as evidence for the theory’s value. In this orientation, students do not use theory to question, challenge, or extend their prior beliefs. Rather, the theory reflects how they see themselves as teachers.

Figure 2. Discursive Patterns GSIs Used to Maintain Teacherly Identity. Bars represent the number of instances when GSIs adopted orientation 1 accompanied by each discursive pattern in each TLR essay.

Adi’s[1] first narrative provides an example of this orientation. She expresses her delight at discovering a theory—expressivism—that supports her belief in a teacher’s power to inspire and energize students. Her visionary view of teaching came from watching Dead Poet’s Society, a film that Adi credits with lighting a “spark of wonder that shaped my teaching philosophy.” Years after seeing the movie, Robin Williams’s portrayal of prep-school teacher John Keating still motivates her to become a teacher who helps students access their deepest thoughts and feelings. She writes in her TLR, “It should come as no shock that [Keating’s] ideas are very connected to expressivism.” Lad Tobin’s call for teachers to exhibit “humanity” and “vibrancy” and an “infectious sense of joy” reminds Adi of Keating’s “honest, funny, and incredibly kind” teaching. Her nascent understanding of expressivism—or a strand of expressivism articulated in a single quote by Tobin—fits with her affect-laden vision of good teaching and appeals to values she adopted long ago.

Other students also use theory to maintain existing beliefs, both positive and negative. This may reflect how they interpret the assignment description’s instruction to put their own experiences and philosophies “in conversation” with theory. For example, Brady believes his transformation from a diffident, unhappy student to a gifted and confident writer came from what he now recognizes as expressivist pedagogy. Similarly, process pedagogy “resonates” with Faith, who valued receiving feedback on multiple drafts of an undergraduate paper. That experience convinced her that the “best” professors give feedback throughout the writing process, not just on the final product. Reese recalls wanting more feedback as an undergraduate student and laments later giving too much feedback as a writing center tutor. She now sees how her negative experiences “go well with” theories calling for a middle road in responding to student writing.

In this orientation, theory gives GSIs new language for their existing conceptions of teaching and learning; in turn, their experiences confirm the theory’s value. For example, because Brady attributes his improved self-efficacy to expressivist pedagogy, he also believes that expressivism can “empower[] students to have the kind of experience which did so much for me.” Theory helps Reese explain why she disliked her professor’s practice of giving scanty feedback; theory also validates her current middle-road (not too much, not too little) approach to giving feedback. Again, GSIs who adopt this orientation often rely on the cite-comment discursive strategy, typically using a single quote from a single theorist to stand for the theory. The straightforward connections they make between theory and existing beliefs sometimes lead them to avoid theoretical complexity. For example, in her first TLR, Faith outlines how process pedagogy “resonates” with her personal philosophy about giving feedback using just one sentence from Donald Murray, while a fuller explanation of process pedagogy may undermine her confidence in this validating sentence.

Quoting and summarizing individual sentences rather than engaging larger conceptual ideas, is a defining feature of the cite-comment discursive strategy, which Faith does in her second TLR:

“[O]ur task must involve engaging students in conversation among themselves at as many points in both the writing and the reading process as possible… ” (Bruffee 642). Here, Bruffee outlines the importance of conversation in our classrooms and how their conversations in the classroom directly impact how well they can read and write.

In another variation of the cite-comment pattern, students follow a quote with a short personal response to the quote. For example, Whitney starts a paragraph with two back-to-back quotes about expressivism, followed by a description of her own experiences that repeats some quoted material: “As I met with my professors to discuss possible writing sample ideas, they seemed happy to discuss my ‘development as a whole person,’ my struggle to live with my anxiety and my moral responses to ideas (Burnham and Powell 113).” Whether GSIs comment on the quote itself (Faith) or comment on their own experience (Whitney), the cite-comment pattern may suggest that students have difficulty engaging deeply with the assigned text, or, perhaps, that their reading of the text was rushed or incomplete. Enculturation into graduate reading and writing practices is a difficult and even overwhelming process for graduate students (Fredrick et al.). Understandably daunted by dense readings or overwhelmed by other responsibilities, GSIs may resort to common writing strategies other researchers have noticed: quoting or piecing together quoted material with minimal commentary (see Howard et al.). For example, Whitney discusses process pedagogy by borrowing language from the source in patchwriting fashion: “Writers are encouraged to be creative with their processes and there are ‘no rules or absolutes’ because the ‘orientation of learning’ leans ‘toward developing the knowledge and abilities needed’ to produce a polished, final product (Tate et al. 217).” Students who adopt the maintaining orientation using a cite-comment strategy allow the source language to speak for them.

As we explain above, our syllabus included multiple theoretical readings for every theoretical and pedagogical approach, and we intentionally created relationships between scholars during class discussions. Still, in individual TLR essays, GSIs often mention only one scholar and do not account for the way scholars debate, elaborate, refine, and refute theory. When students acknowledge theoretical debate, they sometimes treat it as unimportant. For example, Adi, the John Keating expressivist, mentions only that she appreciated the “shortcomings and misconceptions about expressivism” without discussing what those are. All writers—even advanced writers—use distinctive textual strategies when they are learning disciplinary knowledge (Roig). Howard et al. note that an ability to summarize and synthesize indicates a writer’s mastery of subject matter, while quoting and patchwriting suggest the writer is still developing disciplinary expertise. And Chris Anson reminds us that writing in new genres can challenge even the most accomplished writers (“Pop Warner”). Thus, we do not read the cite-comment pattern as indicating deficits in students’ thinking or writing abilities. Instead, we see this discursive pattern as novice scholars’ struggles to understand and engage theory and to write in a new-to-them genre.

This first theoretical orientation—aligning theory with existing beliefs and prior experiences to maintain a teacherly identity—and its associated discursive pattern tell us about the challenges of learning theory. Reid et al. have written that GSIs value prior knowledge above new knowledge. Our discursive analysis suggests that GSIs may value prior knowledge because their new knowledge is tenuous. Their difficulty writing about theory reminds us that they, like all scholars and writers, develop disciplinary knowledge and writing skill over time. Still, it is difficult to speculate on the exact reasons for GSIs’ use of this discursive pattern. It is possible that some GSIs feel intellectually uninvested in or resistant to composition theory, especially considering the literature on resistance in teacher preparation (Ebest; Hesse; Welch). It is also possible that what seems to be resistance is actually identity formation (Grouling) or an act of self-care and boundary setting on the part of GSIs (Schwaller). Additional research could further explore the reasons behind GSIs’ discursive choices and orientations.

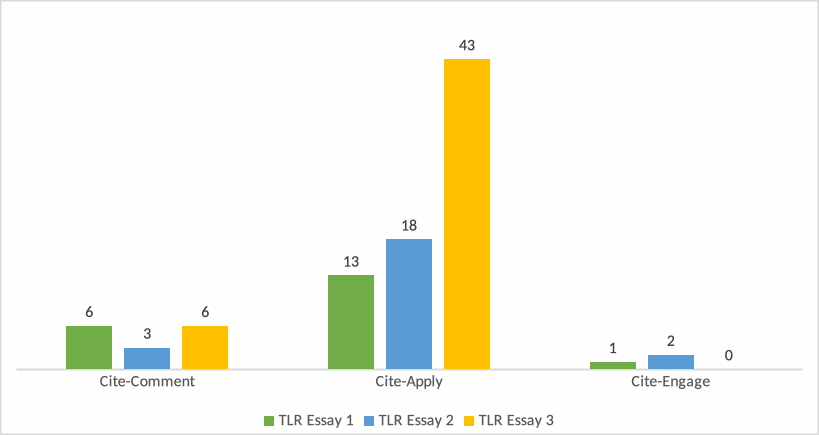

Orientation 2: Shoring Up a Teacherly Identity by Using Theory to Build Confidence or Solve Problems

Our data suggests that GSIs approach theory and research differently when classroom events unsettle and destabilize their self-confidence. In these cases, GSIs sometimes turn to course readings to shore up their teacherly identities, seeking practical answers to teaching challenges in the theory. This orientation appears most frequently in the second and third TLR essays and represents 34% of all orientation codes applied (see fig. 3). Discursively, in this orientation, we most often see GSIs cite theory in order to then make direct application of the theory to their own classroom (cite-apply).

Figure

3. Discursive Patterns GSIs Used to Shore Up Teacherly Identity. Bars

represent the number of instances when GSIs adopted this orientation

to theory accompanied by each discursive pattern in each TLR essay.

GSIs who shore up their teacherly identities turn to theory as a resource and guide for solving perplexing teaching challenges. For example, David describes his teaching insecurities in his very first reflection (unlike many of his peers who are still primarily maintaining an existing ethos in the first essay). He looks to theory and his formal preparation as a lifeboat when he feels like he’s drowning in the storms of first-time teaching. David writes that “learning about pedagogical theory and practice through our [composition seminar]” helped him “feel more and more confident in the fact that [he] could help these students and that [he] had valuable things to teach and share with them” (his emphasis). He credits expressivist theories and Shaughnessy’s ideas about “sounding the depths” for helping him solve a challenge with peer review: after conducting the first peer review, he questioned his students about what was working, listened carefully to their responses, and restructured his approach. Theory builds his confidence in his ability to successfully navigate his role as a teacher. In this first essay, he does not question or complicate the theory and only directly cites one theorist, but he demonstrates a willingness to let theory guide (not just mirror) his approach to teaching by finding new direct applications for it in his classroom.

Carleigh’s third essay provides a good example of a GSI turning to theory to solve a practical challenge in the classroom and to shore up a teacherly identity. Carleigh describes a moment in class when a student responded to her models of writing in an unexpected way—he preferred the “bad” model over the “good” model. In her reflection, she uses a quote from Haswell to explain this moment: “students and teachers operate under very different evaluative sets. Whether it is due to age, gender, expertise, social position, or classroom dynamics, students and teachers tend to consume writing quite differently (Haswell 8).”[2] In the moment with the student in class, Carleigh quickly adapts: she guides the students through a discussion of the strengths and weaknesses of both the “good” model of writing and the “bad” one, negotiating a possible third “best” model that combines the strengths of both. Later, in her reflection, Carleigh processes this destabilizing moment for her teacherly ethos by seeking ways to shore up her teacherly identity, asking herself, “How can I ensure this [difference between student and teacher evaluative criteria] doesn’t happen again?” She brainstorms some immediate possibilities (“constantly evaluating all methods of evaluation,” creating “more time to discuss . . . how my students understand the topic,” planning more flexibly, etc.). She expects that “[t]hese methods (and others which [she hopes] to find in [her] research” will help “prevent [her] from ever again falling into the trap of seeing standards as set in stone.” Her goal is to shore up her ethos and prevent future perceived mistakes.

In this second orientation toward theory, we occasionally see GSIs imagine new applications for theory. Mia’s first two essays, for example, engage theory as a starting place for generating classroom practices and activities. In her first essay, Mia expresses a commitment to mindful teaching, drawing on Shaughnessy’s ideas about teachers “diving in” and “remediating” themselves and an article by Chris Anson on invention (“Process Pedagogy”). She immediately translates this intention into specific practices like spending more time listening to students’ feedback and brainstorming writing topics with students. Mia’s second reflective essay draws on an essay by Amy Devitt on genre pedagogies to generate an activity in which her students analyze the genre of the class discussion board and compare it to the norms of other internet discussion boards. The theoretical readings and her own experiences help her brainstorm additional teaching activities. In both essays, she uses theory to generate practical possibilities for teaching. This kind of generation seems to shore up her confidence in herself as a teacher, since, after sharing the activities she plans to implement, she expresses confidence that they will “work well.”

As Figure 3 illustrates above, in this second orientation, GSIs rely primarily on a discursive strategy we call cite-apply, where they either quote or reference a source and then apply the concept to their own practices as a teacher. For example, Tessa writes about two ways she plans to help students “feel more confident in writing . . . with their own voice like Peter Elbow describes”:

First, I intend to have what I will call “Expressivism Days.”… I want to really carve out time to let my students use writing as a thinking and brainstorming tool.…>

Second, I plan to really emphasize the Writing Center as a place to take concerns about grammar and style.… Although I already emphasized in class the importance of looking at macro concerns before micro concerns, encouraging [my concerned student] to go to the Writing Center seemed to help her feel like I wasn’t trying to trick her by saying that those things don’t matter and then coming back to say, “Well it was on the rubric.”

My hope is that by the next conference, I will see students who have found their voice.

Here, Tessa references Peter Elbow and expressivism before turning quickly to how she will implement these ideas in her teaching. She expresses hope and confidence in what expressivism could do for her students: help them find their “voice.” This second mode of approaching theory is a useful one; it helps GSIs generate activities and ways of teaching they might not have uncovered without exposure to theory. We hope that GSIs will see composition theory as a resource to consult when they face a challenge and are looking for more productive ways to teach. At the same time, we recognize the limitations of seeing theory as an uncomplicated solution to teaching challenges. What happens to these GSIs’ shored-up confidence if these new activities fail or introduce new challenges? The third orientation we identified offers a possibility that we hope will help GSIs accept the uncertainty inherent in becoming a reflective teacher.

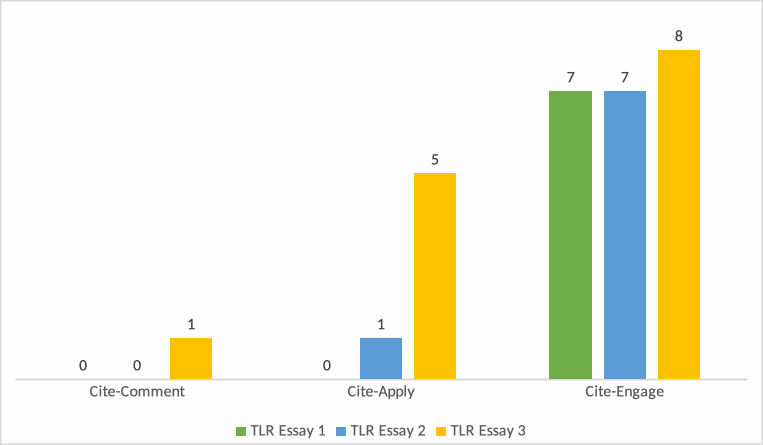

Orientation 3: Becoming a Reflective Practitioner by Accepting Uncertainty

In the final orientation we identified, GSIs interrogate theories in ways that allow them to question both themselves and the theory; find new ways of seeing themselves, their students, and their teaching; and become mindful practitioners. We see GSIs acknowledge and accept that teaching is “messy work” and that they won’t always feel certain or have all the right answers. Fewer GSIs adopted this orientation than the first two orientations (only 50% compared to 100% of GSIs adopting the first two orientations), and it represented only 11% of all orientations coded. This orientation appeared mostly in their third and final reflection, mirroring GSIs’ increased use of the cite-engage discursive pattern (see Figure 4). Because of this, we suggest that both the orientation and the ability to discursively cite-engage theory requires practice, time, and ongoing reflection. In this regard, our graduate students probably resemble most scholars who need time to adjust to new knowledge and new genres (Anson, Pop Warner).

Figure 4. Discursive Patterns GSIs Used to Become Reflective Teachers. Bars represent the number of instances when GSIs adopted this orientation to theory accompanied by each discursive pattern in each TLR essay.

In this final orientation, GSIs use theory as a resource to grapple with challenging questions, and they recognize theory as part of larger conversations with greater explanatory power to frame the complexities of teaching writing. At the same time, these GSIs display more uncertainty and are more likely to acknowledge what they do not yet know as teachers than GSIs using the first two orientations. Here, GSIs rely most heavily on a cite-engage discursive strategy: summarizing theory, synthesizing multiple theorists, and critically evaluating theoretical concepts. They often follow references to theory with questions and reflection about their own practices, about their cultural assumptions, or about the theories themselves.

For example, in her third essay, Rory describes how reading about translingual approaches to teaching writing disrupts and expands her thinking about language in her classroom. Struck by the theory and its “necessary” way of teaching writing, she remains confused about how to best implement it in practice. Rory avoids the assured statements that we saw in her first essays. Instead, she peppers her third TLR essay with questions and statements like this one: “I write about this here not because I know the solution, or can even begin to guess at how we might tackle this monumentus [sic] issue, but because I desperately want to know, myself.” When she refers to her personal experiences in this third TLR, she uses theory to view those experiences in a new light. For example, she says that she now recognizes how White language standards and dominant culture stigmatize the English used by her bilingual classmates and her stepmother (who is not a native English speaker). Rory, a student who feels comfortable using habits of White language, understands that her school experiences have always privileged her (Inoue). In previous situations as a student and TA, she had viewed “language gatekeeping” as “just the way it was,” but reading translingual theory breaks down her prior assumptions and gives her new ways to think.

Although Rory still uses direct quotation as a discursive strategy, in this TLR she cites two theorists rather than just one. She also engages in some summary of these theories. She quotes a definition and considers its implications. Rory writes in her conclusion that she has “loads more research” to do and “so much to learn about” translingualism before she will really understand how to implement it. Her ideas about application are tentative and uncertain, but the energy in her unsettled writing shows her eagerness for the possibilities this theory presents for her teaching: she is “enrapt” by the theory, saying it “fascinate[s] and excite[s]” her and “opens up” new ideas. Interestingly, Rory seems to feel that her engagement is defying our assignment’s expectations. In an aside, she almost apologetically writes that her paper is “more of a teaching and learning exploration than a reflection” (her emphasis). This suggests we could better frame the assignment in ways that invite this kind of exploration. It may also suggest that at this point in the semester (about two months in), Rory is more comfortable sharing with us the aspects of teaching she is still trying to figure out.

Molly similarly questions herself more in her third TLR than in her previous two. She describes following a GSI peer mentor’s advice to “spend a class or two discussing what [she] passionately believe[s her] students need to learn next in order to improve their papers.” Molly decides to focus on clarity in style since she is “a nut” about this topic. But the assigned theoretical readings on style “directly challenge” her decision and make her “reconsider” whether she is serving her students well by focusing on stylistic basics instead of stylistic experimentation. While she previously believed her students didn’t “take risks in their writing” because they were “incapable of considering” those kinds of creative moves, the theory causes her to recognize that her “logic might be flawed and based in [her] own insecurity as a new professor” rather than any empirical truth about her students’ writing abilities. She poses a “poignant question: am I teaching my students to their capacity or am I only teaching to my own?” She answers that she is “humbled” to realize the answer is the latter. She acknowledges a “need to push” herself and commits to changing her approach. Here Molly uses theory to interrogate her teacherly identity and practices, demonstrating mindful engagement with theory.

David, who, as noted above, expressed more uncertainty than his peers starting in his first essay, deepens his engagement with theory in his second and third reflections. In his second TLR essay, David describes encountering ideas about translingualism as an undergraduate writing tutor but says returning to these theories as an instructor “heightened [his] sense of responsibility” to understand and apply these theories in his classroom. One reading provoked a question he “didn’t know [he] needed to ask,” and he realizes that applying translingual theories to the FYW classroom “is much more complicated than [he] had given it credit for.” He willingly interrogates his own thinking about how the theory applies in various contexts. He sees a tension between teaching students “an understanding of standardized, academic English” and helping students “understand and work across differences in language.” He considers how to enact a translingualist pedagogy in his own classroom, including assigning model texts written in different Englishes, like African American Vernacular English or Appalachian English. He hopes his students will accept “the idea that encountering such language usage in their future classes, workplaces, or communities does not mean they are encountering a poorer or ‘lesser’ English, but simply a different one that deserves to be listened to.” He also wonders how the “complicated community” of a university might undercut his own pedagogical goals regarding linguistic experimentation and freedom, such as when his students later encounter a “professor who believes strongly in the necessity of acquiring proficiency in ‘academic English.’” Avoiding the certainty of some TLR essays, David acknowledges the complexity of working in an institution where some ideas may be calcified and where his classroom is not the only influence on students’ writing.

David also explores how translingualism aligns or deviates from other theories in writing studies. While recognizing that critical cultural pedagogies could align nicely with translingualism, he wonders whether genre-based pedagogies would “reject such linguistic freedom in the context of crafting an essential document with established conventions.” David willingly sees and engages the field’s tensions as he builds a personal philosophy of teaching writing. He concludes with a disposition of openness, writing that “it may take a lot more time and thought before” he can decide how to adopt translingualism successfully in his own pedagogy. David’s engagement shows an openness to uncertainty and difficulty that all reflective teachers must practice. GSIs who adopted this third orientation expressed the most uncertainty about their teaching but also expressed a strong understanding of the complexity of teaching. They recognized that one semester would not be enough to resolve this uncertainty; rather, these “wicked” teaching challenges would require long-term engagement with both theory and classroom practice.

Implications for Writing Pedagogy Education

Teaching expertise can come from practice, without any help from theoretical texts and published research. But with Hesse and others, we believe that GSIs become professionals when they understand the systematic ways writing studies scholars explain the practice of teaching writing. One way to do that is through reflection. Although reflection is already often a regular part of teacher preparation, our study demonstrates that a methodical, empirical investigation of GSIs’ reflective work can tell us much about our efforts to prepare teachers. Below, we share the implications of our findings and offer suggestions for creating reflection assignments that help GSIs become theoretically grounded scholars and teachers.

1. Support Theoretical Understanding

Amy’s students often mentioned their reading difficulties in class, sometimes admitting that they didn’t understand anything they read until after discussing it together. Reading theory as a newcomer in any discipline can be frustrating, and putting theory to use in practical situations can seem almost impossible, especially compared to relying on knowledge born of personal experience. To successfully use theory, GSIs must do the difficult work of transfer—building on prior knowledge while integrating new knowledge and adapting theory to new situations and genres (Reiff and Bawarshi; Robertson et al.; Rounsaville). Instead, GSIs sometimes default to personal experience and commonsense, using theory only passingly. If we want our GSIs to become thoughtful, theoretically grounded teachers, we must support them as they struggle with theory, allowing for the kind of mutual flexibility and modification (where the GSI influences the program and the program influences the GSI) that Qualley suggests is necessary for the transfer of knowledge and the development of teaching expertise.

Studying students’ written reflections can alert us to how they are using (or not using) theory and can inform our efforts to scaffold their theoretical understanding. Our research made us think critically about how well our assignments and instruction support our students’ developing relationship with theory. As a result, our research has also changed how we teach. We are now more transparent about our own struggles with theory. While Hesse suggests that we help GSIs see parallels between their experiences and first-year students’ experiences, we now also call attention to similarities between GSIs’ academic endeavors and our own scholarly efforts. We commit to sharing the challenges we experience when encountering new ideas (or rediscovering ideas that have confounded us for years).

We have also added additional reflection activities to our curriculum. Throughout the semester, we ask GSIs to record wobbles in their teaching—moments when they feel disoriented, confused, or uncertain as a teacher (Fecho et al.). In recording their wobbles, we do not require GSIs to engage theory; rather, we encourage them to reflect on the experience and respond with instinct, common sense, and para-expertise. A few times during the semester, we ask our GSIs to share a wobble with other GSIs in weekly instructor meetings. In these conversations, GSIs collectively imagine what the authors of our readings might add to the conversation if they were in the room. We believe that doing this work collaboratively helps GSIs see several things: 1) that their existing knowledge has limits, and peers can help them push beyond those limits; 2) that combining collective experiential knowledge with theory from trusted texts sharpens their thinking about teaching problems, and 3) that understanding theory requires significant time and effort for everyone—new and experienced scholars alike.

2. Teach Summary and Synthesis

Helping new college students read and understand difficult texts is a perennial issue in FYC. As a result, teaching summary figures prominently in many FYC curricula. But discursive patterns like cite-comment and cite-apply suggest that GSIs may also need help reading and understanding texts. With Hesse and Dryer, we think it makes sense to point out parallels between GSIs’ own writing difficulties and the difficulties they are trying to help their students overcome. Our goal as WPAs should be to help GSIs capitalize on their “wonderfully reflexive” position as simultaneously students and teachers (Hesse 225). Still, as Hesse discovered, some GSIs find being compared to first-year students offensive. We soften this by admitting that we, too, feel like novices when we must use difficult sources or sources outside our areas of expertise. We share the strategies we use to grapple, in writing, with new ideas and to write from abstruse sources. We encourage our GSIs to use the same reading strategies—things like adding annotations and other marginalia, constructing T-charts (Jackson), or using reading templates (Boyle)—that we use regularly ourselves. To scaffold GSIs’ learning, we often share our reading notes or model summarizing a theoretical reading. For particularly opaque readings, we may collaboratively create a summary. Or we ask students to work in small groups to explain a theory by synthesizing the work of multiple scholars. Then, finally, we ask them to use theory in their TLR assignments.

3. Teach Reflection

Summarizing decades of research on reflective writing, Brian Jackson states that reflective writing is a place for enacting and constituting identity; a place where writers’ core narratives reveal themselves; and a space where these narratives can be edited, revised, and redirected—enabling newly productive ways of conceptualizing the self (223-224). The question of reflection’s usefulness seems settled. But the question of whether our students understand reflection remains open. Jankens and Latawiec argue the importance of systematically scaffolding reflection—especially in research settings. They caution that reflective prompts should directly address the intended research question. While our TLR assignment directly asks students to connect theory to their teaching and learning experiences, we recognize that our GSIs may not have read the prompt as inviting critical engagement with theory.

Because theory is new to them, GSIs may be inclined to accept theories as truth (or feel that their instructors expect them to accept theories as truth) rather than as propositions to be tested. Hardy, Kordonowy, and Liss found that the language an assignment uses to direct students’ engagement with a reading is “strongly correlated with the dispositions students express when they reflect on their learning.” We now critically consider how the wording of our prompt may fail to “incline [our GSIs] toward curiosity, reflection, consideration of multiple possibilities, a willingness to engage in a recursive process of trial and error, and toward a recognition that more than one solution can ‘work’” (Wardle). Future research could determine the relationship between the reflective prompt and students’ use of theory.

Additionally, the discursive patterns we see in GSIs’ reflections may reveal what students understand about reflection itself. For example, the cite-comment and cite-apply uses of theory we noticed were often embedded in what Kara Poe Alexander calls hero narratives—stories about a GSIs’ individual teaching achievement or accomplishment. This suggests that GSIs may think reflections should tell stories that resolve neatly and establish their success as a teacher. They may have had difficulty reconciling such narratives with theories that expose the tensions, conflicts, and challenges of teaching and learning writing. While some GSIs’ reflective writing revealed their increasing ability to critically grapple with the challenges of teaching, we believe the reflections that told tidy narratives were less productive. Jackson argues that reflective writing can “tell the tale of growth, even if it’s a tale that zigs and zags” (230). We now provide more instruction and scaffolding for reflective assignments. For example, we discuss how the reflection that accompanies growth will likely be a tale of the zigs and zags that are an inevitable part of teaching. We frame reflection as a process of uncertainty and openness. We propose the TLR essays as a place to explore what it means to become a teacher, and we emphasize that becoming is messy and recursive work (Reid; Saur and Palmeri). We tell students that reflection is searching, and not necessarily finding; grappling, and not necessarily triumphing.

As we make these changes to our WPE, we are mindful that this work extends far beyond the semester GSIs spend in our pedagogy seminar. We hope to help them develop habits of theoretical wrestling, strategic reading, summarizing, and reflective practice that they will use throughout their teaching careers. Indeed, these are habits we continue to practice and refine in our own pursuits of better teaching and learning.

Conclusion

As faculty members who study and are responsible for WPE, we constantly seek ways to improve the instruction and support we give GSIs. In recent years, we have been impressed by the abundant research—from writing studies and education scholars—that advocates reflection as a necessary component of becoming successful teachers. Reflection seemed like an answer to our perennial problem of GSI disengagement with theory, and we eagerly integrated reflection assignments into our WPE curriculum.

In doing so, we felt confident that, as the literature suggests, our students would benefit from mindfully reflecting on their teaching and learning. But we also suspected that we could benefit from their metacognitive musings. Specifically, we believed that seeing how they reflected with and through theory might explain why theory often seemed like a thorn in GSIs’ sides rather than a helpful tool. Our systematic investigation into the GSIs’ reflective writing taught us much about the new teachers we mentor and about our own pedagogical practices. We would welcome replication (with any needed adjustments for local contexts and pedagogies) of these results as part of an effort to better understand the impact of reflective writing for new writing teachers (Raucci). Future research on this topic would also benefit from greater triangulation that would help us understand more about why GSIs use specific discursive patterns and adopt certain orientations and how WPE can help GSIs see a greater range of possibilities for theory.

The theoretical orientations we noticed in reflective essays told us that some GSIs use theory to confirm prior beliefs and maintain a teacherly ethos, some turn to theory looking for solutions that will shore up their confidence as teachers, and some embrace theory as a way to explore teaching and become a reflective practitioner. Many inhabit all three orientations at various times. We also learned that the discursive patterns GSIs use can alert us to the orientations they hold. These discursive patterns have become helpful heuristics to guide our teaching. When we see students relying on cite-comment, we believe they may need support in understanding a theory, and we adjust our teaching accordingly. When a pattern of cite-apply appears in students’ writing, we applaud their willingness to turn to theory for answers, and we encourage them to move beyond using theory as a quick fix. And we now try to build on even tentative efforts to cite-engage. We encourage our GSIs to employ theory robustly to investigate teaching challenges, problems, failures, and even successes, knowing that such exploration leads to more mindful teaching for our GSIs and for ourselves.