Composition Forum 52, Fall 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/

“These Posts Would Circulate Because People Love Complaining”: Adjusting Composition Pedagogies in an Era of Virality[1]

Recent studies have suggested that circulation, which is the rhetorical concept defining the movement of texts across space and time during which the texts accumulate meanings and influence rhetorics (Edbauer; Gries), has become a part of students’ writing practices. In Going Public in an Age of Digital Anxiety, David Gold, Merideth Garcia, and Anna V. Knutson demonstrate that students have largely come to understand that writing on social media platforms is permeable and thus capable of circulating quite easily. Many students thus have significant anxiety about their writing circulating in ways that generates backlash or harassment. Students have in turn developed “containment strategies” for their writing, such as posting anonymously or self-monitoring. In “Getting Likes, Going Viral,” Daniel Wuebben surveyed his first-year composition students. He discovered that most of his students assigned higher value to texts based on the number of views and reactions they had. They valued digital circulation over other measures such as the quality of the writing and the writer’s credibility. These students evaluated texts largely based on how widely they had digitally circulated (66-67). These studies demonstrate that many students, through their experiences with social media, have developed an awareness of, values for, and/or concerns about circulation. In turn, these developments have impacted students’ knowledge of, values for, and concerns about writing.

Circulation has seemingly become a part of students’ writing practices. This is not to suggest that students understand the rhetorical theories of circulation. Instead, this point demonstrates that students likely have experiences with circulation that are influencing their writing literacies. Yet most of the current circulation pedagogies focus less on engaging students’ prior experiences with and literacies for circulation and instead on either introducing students to circulation or instructing them on what it is (Ridolfo and DeVoss; Trimbur; Warren-Riley and Verzosa Hurley). Instead, circulation likely needs to be approached as something that is already influencing students’ perceptions of and approaches to writing, and something that is already a part of most students’ writing literacies. Such a shift generates several questions, such as what do students already practice and/or believe about circulation? How are those practices and/or beliefs shaping students’ writing literacies? How can composition pedagogies shift so that they can better engage students’ circulation-related writing literacies? This essay seeks to answer those questions.

To answer these questions, this essay first draws together multiple theories of circulation to articulate a multifaceted definition of the rhetorical concept. This definition articulates how circulation operates in a range of speeds and effects. Such a definition is critical to this essay, and for teaching circulation in composition courses, for it articulates how virality is one of many forms of circulation. Building upon this definition, the essay reviews the existing pedagogies for teaching circulation. The essay demonstrates the limitations of the existing pedagogies in light of the complex definition of circulation as well as students’ prior experiences with and knowledge of circulation. Second, this essay shares the results from an IRB-approved empirical case study of first-year composition (FYC) students. In the case study, students enacted and articulated their prior experiences with and approaches to circulation. The case study reveals that circulation should be treated as a crucial and pre-existing element of students’ writing literacies because various aspects of circulation are already influencing how many students write, read, and understand writing.

Specifically, the case study reveals that every single student possessed some level of understanding of circulation as virality, which is the rapid, fleeting form of circulation that develops on social media platforms (Bradshaw, Rhetorical Exhaustion). This understanding of virality led many students to a series of narrow beliefs about circulation and its role as a writing practice, particularly how and where to compose for circulation. Building upon the findings from the case study, this essay argues that circulation should be taught in much the same manner as important writing concepts like process, audience, and context: circulation should be treated as something students have some knowledge of but need direction in expanding that knowledge. Virality has influenced students‘ writing literacies. Thus, this essay ends with an articulation of the need to engage and expand students’ experiences with and approaches to circulation in composition courses and doing so by teaching students a complex definition of circulation that enables them to critically examine and expand their current understanding of circulation.

Circulation and the Current Pedagogies for Teaching It

In light of students’ prior experiences with circulation, it seems critical that instructors teach a complex, multifaceted conception of circulation that enables students to expand their conceptions of circulation. Fortunately, several complex theories of circulation have been articulated that get at the multiple aspects of circulation, particularly its differing speeds and effects. This essay draws those theories together to establish a complex, multifaceted conception of circulation. First, circulation should be defined as the movement of a text across space and time that occurs after a text has been distributed. The text’s post-distribution movement generates emergent and complex rhetorical activity between the text, audiences, and infrastructures, all of which Laurie E. Gries outlines in Writing to Assemble Publics (330-331). John Trimbur’s work on circulation in Composition and the Circulation of Writing can be added to this definition as he articulates how circulation manifests through the present economic, cultural, and material infrastructures for distributing, discussing, and duplicating texts, be that snail-mail, broadcast television, or social media platforms (194). Finally, Jenny Edbauer’s work in Unframing Models of Public Distribution can be added to these overlapping conceptions of circulation as she articulates how circulation enables publics to either maintain existing rhetorical norms and values or demonstrate alternative norms and values (21-22). Framed via these theories, circulation can be defined as a rhetorical force that materializes in a multitude of forms, speeds, and modes and that shapes public rhetorics when texts accumulate emergent meanings and values through their post-distribution movements and interactions with communities and infrastructures.

Per this definition of circulation, there are slower forms of circulation, as Jonathan Bradshaw has outlined in Slow Circulation. As a response to the constant focus on viral, rapid circulation, Bradshaw researched and outlined how there are forms of circulation that are less digital and move at significantly different speeds. Bradshaw explains that there are “slow” forms of circulation that involve the gradual and persistent distribution of texts across time, sometimes months and years. This more gradual form of circulation requires the participation of multiple individuals. More to the point, its persistence enables it to enmesh with and gradually alter the rhetorical infrastructures and discourses within publics (17-18). As Bradshaw points out, there are also faster forms of circulation.

When understood through a complex definition of circulation, the faster forms of circulation can be situated as another form of circulation that has its own distinct effects on texts, communities, infrastructures, and discourse. Virality is one such “fast” form of circulation as the rapid circulation of a text on and/or across social media platforms. Virality can engender new rhetorical possibilities within large publics. It has also led to the calcifying of infrastructures and discourses within publics (Bradshaw, Rhetorical Exhaustion). It also often exposes texts and writers to unintended and typically hostile audiences (Gold et al.). It has also engendered new, un-critical forms of reading in which the priority of individuals is to quickly respond instead of critically engage with texts. Put differently, virality often engenders un-critical forms of reading (Powers; Wuebben).

In bringing these theories of circulation together, viral circulation can be situated as one form of circulation among several others. Defining virality as one form of circulation is significant as it generates distinct possibilities for teaching virality. Specifically, virality can be engendered as one form of a broader, more complex aspect of students’ writing literacies. In turn, a broader conception of circulation can then be used as a framework for expanding students’ writing literacies. In situating virality as one of several forms of circulation with its own speed and effects, students’ prior knowledge of virality can be situated as a partial understanding of circulation. Students can then have their experiences with, and prior knowledge of, circulation validated and then clearly tied to a larger rhetorical concept, which can in turn be used to expand the students’ experiences and knowledge. Furthermore, the complex definition of circulation helps instructors identify what other aspects of circulation to teach. There are currently several pedagogies for teaching circulation, each of which engage with some aspects of circulation.

Several circulation pedagogies have been developed that enable students to learn about various aspects of circulation. While they engage differing aspects of circulation (more on this later), the existing circulation pedagogies share a central focus on having students learn about circulation and some of its effects on writing, writers, and/or audiences. These pedagogies all generally start from the position of introducing circulation as a rhetorical concept that will broaden students’ writing literacies. Thus, each of the current circulation pedagogies have limitations, particularly if examined from the perspective of students already possessing limiting believes about and/or practices for circulation. However, they also offer something invaluable if the goal is to teach students a more complex definition of circulation.

First, some pedagogies center on having students compose for circulation and/or teaching students composing strategies for generating circulation. These approaches offer a vital starting point for establishing connections between circulation and writing literacies, but they also have several limitations given what appear to be many students’ experiences with virality. Students’ experiences suggest that many students are cautious about composing for circulation. Teaching students to compose for circulation was first popularized by Jim Ridolfo and Danielle Nicole DeVoss with their composing strategy and corresponding pedagogy titled “Rhetorical Velocity.” Rhetorical Velocity involves composing texts in ways that motivate audience members to recompose, share, and otherwise circulate the text. Ridolfo and DeVoss encourage composition teachers to have students compose for rhetorical velocity. The co-authors argue that the concept will enable students to better understand the possibilities and risks of composing in our contemporary, digital-saturated writing environment.

Others have taken a more general approach by having students compose for circulation and then using their composing experiences to think more critically about writing. Tait Bergstrom outlined such an approach in his article Remediation that Delivers. He had his students compose and distribute multimodal texts into digital communities. His students then tracked their text’s circulation on social media platforms. They then reflected upon how their texts were circulated by members of those communities. Their reflections enabled them to develop a more complex understanding of how communities take-up and remix texts, languages, and genres.

In having students either learn composing for circulation strategies or composing for circulation, these teachers find that circulation enables students to start grappling with the various ways how to write in our contemporary digital environment (Bergstrom; Ridolfo and DeVoss). Yet, this pedagogical approach to circulation does have significant limitations. First and foremost, it does not engage with any of the concerns or prior beliefs students might possess about the ways digital circulation can negatively affect them as writers. What would students who have developed “containment strategies” against their writing’s potential circulation (Gold et al.) do with strategies for composing for circulation? Second, these approaches might be redundant or even limited compared to the composing for circulation strategies students might have already developed.

Another approach to teaching circulation has students examining the circulation of texts and rhetorics within publics. This approach offers a useful context for teaching circulation. However, this approach also has significant drawbacks given that many students’ current experiences with virality are more mundane and might feel separate from pedagogical engagements with publics and public rhetorics. John Trimbur first articulated this approach in Composition and the Circulation of Writing. Trimbur taught composition students Marxist cultural theories. His students then used the Marxist theories of distribution and the flows of power to trace the circulation of texts. Through their tracing, students developed a sense of how the circulation of texts generate credibility and authority within publics. Building upon this work, Jenny Edbauer articulated an approach that had students study the production of and mutations of rhetorics within publics. In Unframing Models of Public Distribution, Edbauer had students track the formation and continued circulation of rhetorics within publics. Her students tracked how specific rhetorics form and then accumulate new meanings, uses, and effects as they circulate. This approach to teaching circulation offers an invaluable understanding of some of the contexts and effects of circulation. It also offers students a site through which to study and observe circulation. However, this approach also seems divorced from the daily writing practices and beliefs that engender much of composition students’ writing literacies. By extrapolating circulation so that it centers solely on public rhetorics, this approach risks situating the circulation taught in classrooms as only considered with broader publics, public rhetoric, and norms and infrastructures. Such a focus on broader public rhetorics elides the circulation students experience in their own writing practices, circulation that is inter-personal, risky, and tied to social media metrics.

Another approach to teaching circulation blends elements from the other two approaches by having students compose for circulation within specific publics. This approach blends the two aforementioned approaches to establish a situated and composition-centered approach to teaching circulation. However, this approach also fails to engage with the individual fears and concerns about circulation that many students seem to have. In Multimodal Pedagogical Approaches to Public Writing, Sarah Warren-Riley and Elizabeth Verzosa Hurley outline what they call a more “mundane” take on this approach. They had students compose in multimodal genres that both likely engendered circulation and that the students likely already had prior experience with, for example memes. The co-authors then had students compose the texts about contemporary public issues. From there, students reflected on their experiences to develop practices for performing advocacy through their own, “typical” writing practices (Warren-Riley and Hurley).

Others have articulated more advanced approaches, such as Paula Mathieu and Diana George. Mathieu and George had their composition students partner with local community organizations. The students then supported the organization by learning about circulation and composing and distributing texts that furthered the circulation of the discourses the organizations were engaged in. Laurie E. Gries took this approach a step further in Writing to Assemble Publics. In a capstone composition course, Gries had her students spend an entire semester working to generate a public around an under-considered local issue. The students did so by learning about public rhetoric and circulation studies, and then using those theories to compose, distribute, and further the circulation of texts about the under-considered local issues (Gries). This pedagogical approach provides students with a context—publics—through which to situate and develop circulation composing practices. This approach certainly corrects for some of the issues with the other approach to teaching circulation as tied to public rhetorics for it has students write in more “mundane” and everyday ways. Yet rooting approaches circulation in publics still abstracts writing for circulation away from the ways many students write outside of the classroom. It also risks failing to connect with the more personal aspects of circulation, particularly the ways many students evaluate texts based on their digital-circulation metrics and/or the fears many students have about their own personal writing circulating to unintended audiences.

The existing circulation pedagogies offer strong frameworks for introducing students to circulation, yet they have significant gaps when considered through the perspective of students already having prior experience with circulation and thus needing more complex conceptions of circulation. Strategies for composing for circulation likely seem misguided to students if many of them already have their own composing strategies that seek to prevent their writing from circulating. Furthermore, situating circulation within publics, either generally or locally, risks failing to connect to students’ existing circulation practices and beliefs particularly if those practices and beliefs are defined through individual contexts and experiences. Lastly, if students are already grappling with a specific form of circulation, then pedagogies that engage circulation need to foreground and explicitly engage that form of circulation. Otherwise, they risk introducing circulation as something separate from students’ existing practices and beliefs: if students understand “virality” and their courses engage “circulation,” students might struggle to connect the two.

Put differently, if the one of the main goals of circulation pedagogies is to expand students’ writing literacies, then students’ existing circulation-related prior knowledge needs to be foregrounded and built upon, which is something the existing circulation pedagogies do not do. What composition instructors teaching circulation need is a sense of what many students already practice and believe about circulation and ideas on how to adjust existing circulation pedagogies to engage those practices and beliefs. Only when instructors have a sense of what composition students already understand about circulation and/or virality can they start to determine what other aspects of circulation they need to teach. To offer some sense of what students already practice and believe about circulation, I present my case study of first-year composition students’ and their existing circulation-related composing practices and beliefs. The findings from my case study demonstrate the dual need for composition courses to engage circulation and to do so from a different point than those suggested by the existing circulation pedagogies.

A Case Study of FYC Students’ Experiences with Circulation

The case study I designed aimed to study some students’ prior experiences with, beliefs about, and compositional practices for circulation. To do this, I designed both a circulation-focused project for a FYC course and an IRB-approved study of both the project and students’ prior circulation-related practices and beliefs.

I created and taught an FYC project that drew upon aspects of all three of the circulation pedagogy approaches. In the project, students studied and then composed responses to local campus issues. They then composed three different texts in response to the issue. They wrote each text so that it sought to generate circulation with a different local audience. They wrote an email to someone at the university who could do something about the issue, a letter-to-the-editor for the university newspaper, and then a text of their choice that they felt would circulate among their fellow university students, such as a Facebook post, an Instagram story, or a video. Students also wrote a reflection about each text. In the reflections, students explained how and why they thought their text would circulate, focusing on how the audience and the genre they were writing in influenced the potential circulation of their text.

The project arrived at the mid-point in the semester, and I had spent considerable time earlier in the FYC courses building to it. I focused the prior two projects on having students write about and build knowledge upon their prior experiences as writers. Students wrote about their writing experiences and connected those experiences to rhetorical theories. For example, I had students write an essay in which they wrote their own definition of rhetoric. Their definition had to draw upon their own personal experiences with writing as well as established rhetorical theory. I spent considerable time in the semester preparing students for the circulation project and, important to my case study, for articulating their own experiences with and knowledges of circulation in conversation with rhetorical theories of circulation. Furthermore, as a white, middle-class, cis-gendered male, I likely benefited both with the project and in the data collection from students’ willingness to view my requests to write about and examine their experiences as writers as valid subjects for an FYC course.

I then performed the case study in which I collected and analyzed the students’ work for the aforementioned project. I collected data from 23 students from three different FYC sections taught during the 2018-2019 academic year. Fifteen of the students identified as women and eight as men. The students were between the ages of 18 and 20 and were either first- or second-year students. The students came from a range of majors, none of which were English. Drawing upon university data, many of the students were likely first-generation college students—over 50% of the student population at the university at the time—and/or receiving some form of financial aid—over 75% of the student population at the university. Nineteen of the students identified as white, three identified as African American, and one as Asian American. The student dynamics reflect the rural, mid-western university where this case study was performed.

To collect the data from these students, I emailed them after the FYC course ended. In the email, I asked them to participate in the study, and I offered three different levels of participation. First, students could submit their course work for analysis. I requested and received access to all the texts the students created for the circulation project, gathering everything from brainstorming docs to reading responses to completed texts to reflections. 23 students agreed to participate at this level. I thus got access to a total of 89 texts. I analyzed the students’ work for the circulation strategies they enacted. I wanted to know how they composed for circulation, specifically what rhetorical moves or writing processes they enacted to attempt to generate circulation. I also paid close attention to the students’ reflections on their work; I sought to understand how they defined and/or understood their writing practices, both in general and for circulation. This data provided a sense of how students composed for circulation and how they understood their composing practices.

At the second level of participation, students submitted their course work and agreed to complete a survey that I sent in a follow-up email. 15 students completed the survey. The survey inquired into students’ prior experiences with and perceptions of circulation. The survey asked students about how they valued circulation, what effects they felt circulation had on their writing, and what knowledge of circulation they had prior to the course. The survey offered information on what students understood and believed about circulation. It offered a way to inquire into students’ broader, general perceptions of circulation.

At the third level of participation, students submitted their course work, completed the survey, and agreed to a follow-up, in-person interview about their experiences with circulation in the course and beyond. Seven students participated in the interviews. I conducted the interviews a few weeks after the students had submitted their work and completed the surveys. I wanted to be able to ask students about their work and the general responses from the survey. So, I interviewed several students about their experiences with the project and how they drew upon any prior composing practices for and beliefs about circulation in the project. In my interviews, I sought to connect the data from the survey to students’ texts. So, I inquired into individual students’ broader knowledge about circulation—drawing statistics and comments from the survey—and trying to see how students felt that manifested in the ways they composed their texts for the projects. The interviews offered a way to try to connect students’ broader perceptions of circulation to the individual composing strategies that they enacted.

I applied a grounded theory approach to the data (Charmaz). I did an initial pass on the data looking for any connections across the three data sets. Two questions guided my analysis: what literate practices did students enact with regards to circulation (reading, writing, sharing, etc.) and what did they believe about circulation and its effects? I used these two questions to develop codes out of the data. The questions lead to both a general finding and four specific findings about students’ practices for and beliefs about circulation.

The case study was not designed to be a fully representative study of FYC student practices for and beliefs about circulation. The case study merely sought to use its limited data to help composition instructors identify the need for and new starting points for pedagogical considerations of circulation in FYC courses. The results of the study illustrate some of the many possible aspects of circulation that students already understand prior to entering a composition course. The case study offers a useful albeit limited understanding of some composition students’ composing practices for and beliefs about circulation, an understanding that demonstrates the need to shift and expand how we understand students’ experiences with circulation and in turn how we engage circulation in composition courses.

Case Study Findings: Student Practices for and Beliefs About Circulation

General Findings

I read through the data hoping to gain a sense of students’ practices for and beliefs about circulation; in particular, I wanted to locate practices or beliefs that students expressed in all three data sets. I wanted to see, for example, if students enacted a composing practice for circulation, noted something about the practice in the survey, and then explained something about that practice in interview statements. In my first pass through the data, I realized that these students believed circulation held significant rhetorical value, yet there were also significant variations in how each student individually valued it. These students also had a range of different practices for circulation. Seven of the fifteen students who completely the survey explained that they regularly composed texts that they hoped would circulate. The other eight students who completed the survey were aware of circulation and believed it to be significant but otherwise did not compose for it. On one end of the spectrum were students like Aiden (student names are pseudonyms) who regularly composed for circulation on social media and, in his interview, expressed a sense of how circulation shapes the value and meaning of all writing. On the other end were students like Laura who explained in her interview that she knew of virality and thought it was important but that she didn’t use social media and that she generally tried to write in ways that would prevent her writing from reaching unintended audiences. This range suggests that the students possessed a general belief in the value of circulation but had a diverse range of experiences that led to those beliefs. Circulation influenced seemingly all the students’ literacies, but the influence arose through very different sources, be it personal writing experiences (Aidan) or being aware of it from external sources (Laura).

Despite the differences in their experiences with circulation, the students shared a baseline understanding of circulation. They all understood circulation as something connected to their experiences with and/or understanding of social media and the rapid, fleeting circulation that occurs on it, a.k.a. virality. Every single student in the study mentioned virality. The students also had a clear sense of what virality is; as Zendaya defined it in her interview “Going viral means that a post (tweet, vine, video, song, Instagram post, etc.) had circulated very quickly on the Internet and it was trending.” All the students in this study had both a belief in the rhetorical value of circulation and had some knowledge of one form of circulation.

Yet the students’ beliefs and knowledge about circulation were largely only knowledge about virality. They understood virality and then used that knowledge to guide the ways they composed for and reflected upon circulation. The students in this study largely understood circulation to be virality. Seeking to better understand what aspects of virality students had composing practices for and/or beliefs about, I re-analyzed the data. In my second analysis, I sought new codes that would help me identify student practices for and beliefs about virality.

In my second analysis of the student data, four thematic codes emerged that demonstrated key components of students’ practices for and beliefs about virality. I learned that students ascribed a high and general value to virality. Nearly all the studied students viewed generating virality as a significant and worthwhile outcome for writing, and almost all the students said that they personally valued writing that had gone viral. Second, I learned that many students viewed composing for virality as a risk. More than half the students in the study did not compose for virality on their own and nearly all the students expressed concerns about the risks that arise from composing for virality. Third, I realized that students had several composing strategies for generating virality. Fourth, I recognized that students understood the intense emotional reactions of collective audiences to be central to virality.

The High Value the Students Ascribe to Virality

All students in the study believed that virality was a significant rhetorical effect. Specifically, they believed that texts that have gone viral have an increased rhetorical value. As Ella explained in her interview, “I think I automatically value something more if it is viral because if it has been circulated by thousands of people, that is a good indicator that whatever the post may be [it] has some sort of benefit/worthiness.” These students believed that if a text had gone viral, it had increased rhetorical significance and value. Thus, the students in this case study suggest the need to expand beyond the prior pedagogical approaches to circulation. Students already value one form of circulation. Thus, they do not need to be introduced to circulation. Furthermore, any pedagogical engagement with circulation needs to engage the form of circulation students value, virality, or it risks situating circulation as something other than virality.

Building upon the high value they ascribed to virality, nearly all the students were developing their writing abilities through observations of viral texts. One survey question asked students “What types of writing influence your writing?” In a check-all-that-apply series of provided responses, 13 of the 15 students checked that they learned from “Viral texts that appeared in their social media feeds.” The only choice that received more responses was “Texts assigned in classes,” which all the students checked. Viral texts have a significant impact on many students. Viral texts influence how students develop as writers, reaching levels of importance that rival the texts assigned in classes. This suggests that students are learning from viral texts that they encounter outside of composition classrooms. For example, one student when asked about what types of texts they learn from explained in the survey that they learn from “tweets and memes created only for humor.” Students are noticing these texts and developing ideas about writing from their encounters with viral texts.

The students also viewed virality as a rhetorical effect that writers should compose toward. In the survey, students were asked, “In our current writing environment, how important do you think it is for writers to have their texts circulate?” Students were then asked to rank responses from 1-10, with the explanation that 1 meant “doesn’t matter,” five meant “equal to other aspects of writing,” and 10 meant “the most important thing” (see Figure 1):

Figure 1: Results of a survey question asking students how important they believed it was for writers to compose for circulation.

Per the framework of the question, students viewed writing for virality as somewhere between “equal to other aspects of writing” and being somewhat more significant than other aspects of writing. For all but two of the students, virality was at least equally as important as other aspects of writing. Even more telling, no students marked writing for virality as unimportant. There is a sense among these students that composing for circulation is worthwhile and important. It is something that writers should be doing and that should be a regular part of their composing practices. According to these students, composing for virality is something contemporary writers should be doing.

Combined with the general value the students ascribed to virality, these findings suggest that for these students virality is both a broadly significant rhetorical force and an important part of contemporary writing practices. Many of these students highly valued virality, learned from it, and thought that writers should write toward it. Pedagogically, these findings suggest that circulation and virality should be engaged in writing courses, particularly FYC courses. If an instructor does not engage virality in some form, they risk disregarding something many students view as an important part of contemporary writing practices. More to the point, most instructors should work to engage students’ pre-existing knowledge of circulation, drawing out and defining with them their believes about and valuing of circulation.

Writing instructors should teach circulation and they should teach it as something that many students already have beliefs about. This means that circulation needs to be approached as something that many students already partially understand. Many students have beliefs about virality, viewing it as an incredibly valuable aspect of contemporary writing literacies. This suggests an important starting point for pedagogical engagements with circulation. Students should share and articulate their beliefs about circulation. This is something lacking from many of the current circulation pedagogies; there is no acknowledgement of nor attempts to draw out students’ prior experiences with and/or practices for circulation. Only after students have externalized those beliefs can they work to start expanding and/or revising them.

Virality as Risk

Drawing out student beliefs about virality is important because students likely have complex perspectives on it. Despite the generally high value most of these students placed on virality, they had diverging perspectives on composing for virality on their own. In the survey, students were asked in a check-all-that apply question what goals they wrote for outside of classes. Seven of fifteen students checked that they wrote for virality. Thus, less than half the surveyed students wrote for virality. This meant that many of the students valued virality but were not necessarily writing for it on their own. This finding suggests the students have complicated beliefs and practices for virality. They understand it. They view it as something that adds value and meaning to texts. They observe and learn from it. They also view it as something writers should write toward. But they do not necessarily write for it themselves. This does suggest the need for pedagogies that teach students’ composing for virality strategies, something others, Ridolfo and DeVoss and Bergstrom, have already suggested.

As to why many of these students were not writing for virality despite 87% of the students learning from viral texts, many students expressed concerns about their writing generating unintended reactions. An open-ended survey question asked students if and how they wrote for audiences beyond their immediate audience. Fourteen of the fifteen students explained that they changed their writing process in some way when writing for audiences beyond their immediate one. In their explanations as to how they changed their writing, the students explained that they were extra diligent about their grammar and spelling and that they made sure that their writing was clear and difficult to misinterpret. As one student explained in the survey in response to a question about how their write for audiences beyond their immediate one, “I think harder and longer about what I’m going to write before I actually write it. I also pay more attention to grammar and spelling to make sure anyone else who would come across my writing would be able to understand it.”

Several students explained that they altered their writing process to prevent appearing foolish and prevent negative reactions from secondary audiences. These findings echo Gold, Garcia, and Knutson’s findings about contemporary writing students’ concerns and anxieties with digital writing. In combination, these findings suggest that students understand quite a bit about the possibilities and challenges of composing for virality, and that knowledge has learned to concerns about their own writing circulating. This aligns with a point that Gold, Garcia, and Knutson made in Going Public. They write that “Not only must we assist students to strategize the ways that one’s writing might be remixed or taken up by imagined or targeted audiences (Ridolfo and DeVoss), we must also devise strategies for assisting students in responding to unimagined or untargeted audiences.”

In sum, these students valued virality and were in turn developing their writing abilities in complex ways around those values. This suggests that virality, and by extension circulation, has a significant effect on many students writing literacies. It is influencing how students think about writing. It seems that many students view virality as something they should draw ideas from and that writers should write for it. Eighty-seven percent of the students were making connections between the viral texts they observed and their own writing practices. Nearly all the students believed that composing for virality requires altering one’s composing practices and putting oneself at risk for misunderstanding or conflict. For some students, this was an acceptable trade-off for composing for virality, but for more than half the students the challenges and risks of composing for virality presented a significant barrier to composing for virality.

Pedagogically, this suggests a need to teach circulation not only as a composing possibility but as a composing risk. Teachers should not teach circulation as a purely positive, generative aspect of writing practices, such as suggested by Ridolfo and DeVoss, Bergstrom, or Edbauer. Virality, and by extension circulation, should be treated as a risk for writers. Virality might engender hostility and harm to writers. This sense of virality as risk is something many students already understand. To ignore this aspect of virality is to ignore how many students think about the act of composing for virality on their own. Thus, instructors should look to directly engage with students’ concerns about the risks of their writing going viral, as Gold, Garcia, and Knutson suggest; this is only something that can happen after students have shared and defined their experiences with circulation. Thus, instructors should look to start with students’ prior experiences with circulation, naming, defining, and valuing them, and then building into students’ practices for virality. For my case study also revealed that many students–despite over half of them not composing for virality on their own—understood specific strategies for composing for virality.

Students’ Existing Strategies for Composing for Virality

Twenty-two students in this case study enacted strategies for composing for virality, or what I will now call “composing-for-virality strategies.” By strategy, I mean either a specific rhetorical move made within a students’ project that would affect the text’s chances at virality or an explanation of a rhetorical move in a student’s reflection on the project. For the most part, the strategies appeared in the texts the students composed. Students enacted specific strategies to generate circulation for their texts. Several students also articulated their strategies in the reflections they wrote for the projects. The mere fact that all but one of the students enacted composing for virality strategies demonstrates that students need more pedagogically than to be introduced to composing-for-circulation strategies (Ridolfo and DeVoss).

Three strategies appeared in at least half the students’ texts and/or reflections. The strategies were referencing pop culture, distributing texts kairotically, and drawing upon the affordances of social media platforms. In terms of how many students enacted each strategy, the breakdown was:

- 12 of 23 students made pop culture references

- 13 of 23 students outlined ideas about how to kairotically distribute their texts

- 18 of 23 students composed differently for social media platforms and/or explained how they made writing decisions based on the affordances of specific social media platforms

Many students enacted multiple strategies in their texts, such as referencing pop culture and drawing upon the affordances of a social media platform. Each strategy, though, suggested something different about these students’ practices for and beliefs about virality.

Roughly half the students composed for virality by incorporating pop culture references into their texts. Several students created texts that either used imagery from movies or incorporated well-known pop culture quotes. For example, one student, Dan, wrote this Tweet about the parking issue on campus, “A long time ago, far far away there once was a parking spot open to those who were very lucky.” In explaining this strategy in their reflections, many students expressed an understanding that pop culture was something that can be incorporated into one’s texts to increase the possibilities for virality. As Dan wrote about the tweet in his reflection, “I feel that the post will do well because it’s relatable and it references Star Wars.” As students explained in their reflections, students believed that referencing pop culture was a way to attract attention by referencing something their audience would understand, relate to, and/or enjoy.

Supporting the previous finding, students also articulated a distinct belief about the need to consider one’s audience when composing for virality. The students believed that if writers want their texts to go viral, they must incorporate information their audience values. In a select-all-that-apply survey question that asked students what writers needed to do to make their texts go viral, 13 of 15 students selected “Incorporate information and/or ideas that the audience values.” Students believed that composing for virality involved engaging their audience through texts, references, or ideas that they valued. This demonstrates that many students believe that composing for virality requires knowledge of and engagement with specific audiences and their values, norms, and/or prior textual circulations. This suggests that students are somewhat aware of the aspects of publics and audiences and their role in publics. Students are already engaged with the ways already-circulating texts shape the rhetorical possibilities within publics, or at least with audiences.

Thirteen students enacted a composing-for-virality strategy that involved distributing their texts at a specific time of day. The students explained that at those moments during the day their audience was either more likely to read their text or to share it. With this strategy, students demonstrated a deeper understanding of virality. They understood that virality didn’t simply happen through composing decisions made by the writer. Instead, they articulated a sense of how the audience and composing decisions intertwined to create opportunities for virality. For example, one student, Ellie, wrote in her reflection that “I would post this in the morning around 8 A.M. Most of my followers/audience on here are students. I also feel like students are big on Twitter, and many of them check their feed before class starts for the day in the mornings.” Ellie’s remark demonstrates both an understanding of how the time of day and the distribution technologies influences the potential virality of her text. Building upon this point, the most common strategy students enacted involved composing for a specific social media platform.

Eighteen students enacted composing strategies for social media platforms. These strategies seemingly arose from the students’ personal writing experiences. In a check-all-that-apply survey question, students were asked what types of writing they did regularly; 14 of 15 surveyed students checked that they regularly wrote for social media. Furthermore, in their project reflections explaining their composing-for-virality social-media strategies, all 18 students identified specific social media platforms they were composing toward for their projects, such as Twitter, Facebook, or Instagram. Students also explained how the individual platforms had specific affordances that enabled their texts to either circulate through or for audience members to use to circulate their texts. For example, Giselle explained in her reflection that “Twitter is an effective platform to share ideas on because people can circulate them by retweeting, liking, using a hashtag, and replying to tweets.”

Many students also noted how they changed their writing style for specific social media platforms. As Ella explained in her interview, “I don’t necessarily change my writing process so much as just adapting how I express myself. When writing beyond my immediate audience, I try to adapt my writing to fit the ‘where’ of where I’m posting. Using different abbreviations and lingo based on the [social media] platform.” These students altered their composing practices for virality and for specific social media platforms. They understood how the affordances of social media platforms shaped what their audience could do with their texts. Despite less than half the students composing for virality, nearly 78% of the studied students had developed social-media-specific composing-for-virality strategies.

For almost all the students, social media was the site, or as Ella called it, the “where” of virality. The students understood the affordances of the social media platforms they personally used and how and why virality manifested on those specific platforms. They believed social media, and the affordances of social media platforms, to be the infrastructure for virality. They understood singular social media platforms and the virality that developed on them. They, however, lacked an understanding of how virality could spread across platforms or even beyond social media. They did not have a sense of the ways circulation works across social media platforms or amidst larger networks.

Many of the students explained in their reflections that they composed their texts for a specific social media platform because they personally used that platform. Students composed, for example, Tweets or Instagram Stories for their course projects because those were the platforms they personally used. As Tim explained in his reflection on the Tweets he created, “I would post these posts on Twitter mostly because I do not use any other form of social media. I do have an Instagram, but I never really post anything on it. I would also use Twitter because I see a lot of rants on there about college and how stupid some things are.” Students drew upon their own experiences to develop and/or enact composing-for-virality strategies. Students drew upon their personal social media practices to inform how they composed parts of their circulation course projects. These students had significant practices for and beliefs about social media and its impact on virality and writing, yet those practices and beliefs were filtered through their personal uses of social media. This finding suggests one aware where public-rhetoric focused circulation pedagogies could be particularly useful; students could be provided theoretical frameworks for understanding publics and then use those frameworks to study how texts circulate across platforms, shaping publics (Edbauer; Gries).

More to the point, these findings about these students’ composing strategies suggest that writing instructors should engage social media, both in general and when teaching circulation. Social media is influencing how students write (Gold et al; Wuebben); even students who do not compose for virality on their own still understood and enacted strategies to compose for circulation on social media. In writing classrooms, students’ practices should be validated and then connected to a more critical and expansive definition of circulation. If instructors do not engage social media when they teach circulation, they will make it incredibly difficult for students to connect their existing practices for and beliefs about circulation, and writing, to circulation.

Despite its presence in most of the students’ projects, reflections, and survey data, social media was not the most important thing that students articulated in terms of their practices for and beliefs about virality. In their project reflections, survey responses, and interviews, students explained a deep understanding of the role that collective audiences play in driving virality.

Students’ Sense of The Role of Audience Emotions in Virality

All but one of the students in the case study articulated an understanding of the importance of audiences to virality. Twenty-two of the twenty-three students wrote in their reflections about different things they were doing in their texts to engage their audience. Many of the students explained in their reflections that virality would only develop if audience members were interested in and/or directly engaged by their writing. As Aiden explained in his interview, “Virality is all about how people respond to the text and who a text gets exposed to initially…. It is about getting a text to the right people…. If you can’t get anyone to react to your writing, they aren’t going to spread it, and it is not going to go anywhere.” In conjunction with their composing-for-virality strategies, many students had developed a sense of how writing for virality entailed writing for audience members’ reactions.

Students believed that for virality to develop, the emotions of audience members had to be engaged. As one student explained in an open-ended survey question inquiring into students’ thoughts about the differences in how they personally write for class versus social media:

If I am writing beyond my immediate audience, I will usually put more effort into the brainstorming and preparation for my text. This could be searching for similar texts, reading others’ opinions on the topic, and getting a good understanding of my audience by what they post, what kind of writing they interact with, etc.

The students had composing-for-virality strategies that involved both strategies for the style and distribution of their texts and strategies for engaging the known reactions of audience members. Many of these students detailed writing-for-virality strategies that focused on either writing to provoke a known reaction in their audience or writing to counter potential unintended reactions. For these students, composing-for-virality strategies were not only about composing texts for the right time of day and the affordances of a social media platform, but it was also about writing for the way audience members would react at that time of day and on those platforms. These students had a sense of the role of public values in circulation. While they likely would not use the terms “publics” nor “values,” they did articulate an understanding of one of the core components of public-engaging circulation pedagogies: the need to engage what audience’s value.

These students also identified specific audience reactions that they believed propelled virality. For these students, virality arose through intense and affective audience reactions. As Zendaya explained in her interview:

I think that for something to go viral, it must be heartwarming, funny, or horrible. People tend to react to extremes, which is why I say it’s at both ends of the spectrum. We see the videos of military parents surprising their children all the time because they make us feel good inside and remind us that the world is not completely terrible. On the other hand, awful things go viral, such as police brutality.

Virality arises for these students not through audience reactions in general, but through extreme emotional reactions. Nearly all the students in this study believed that an audience’s anger and/or sense of humor drove virality. Ella explained in her interview that “I think about one of the best ways to present the information in a manner that gives it the best chance to be circulated. This could be by adding humor in a way or by displaying my writing in a controversial way to get more people talking about it.” Echoing Ella’s sentiments, another student, Tim, shared in his interview his beliefs about what makes texts go viral, and that is that a text is “Funny or simply on a popular topic that a lot of people either relate to or are infuriated by.”

Further reinforcing this point, in the survey, students were asked “What characteristics do social media posts need to circulate?” Students were then provided a range of options, covering everything from length to visuals to four different options for the tone of the writing. Students were then asked to check all that applied. Twelve of 15 students said a viral text needed to have a “Humorous Tone.” The only options from that list that received more selections were “Incorporates Visual Elements” (13 of 15 responses) and “Brief Word Count” (13 of 15 responses). This suggests that for these students that when it comes to generating virality, the affective elements of the text were second only to what are generally assumed to be common characteristics of social media writing, which are its brevity and its visual elements. Most of these students possessed a belief that virality develops through intense audience emotions.

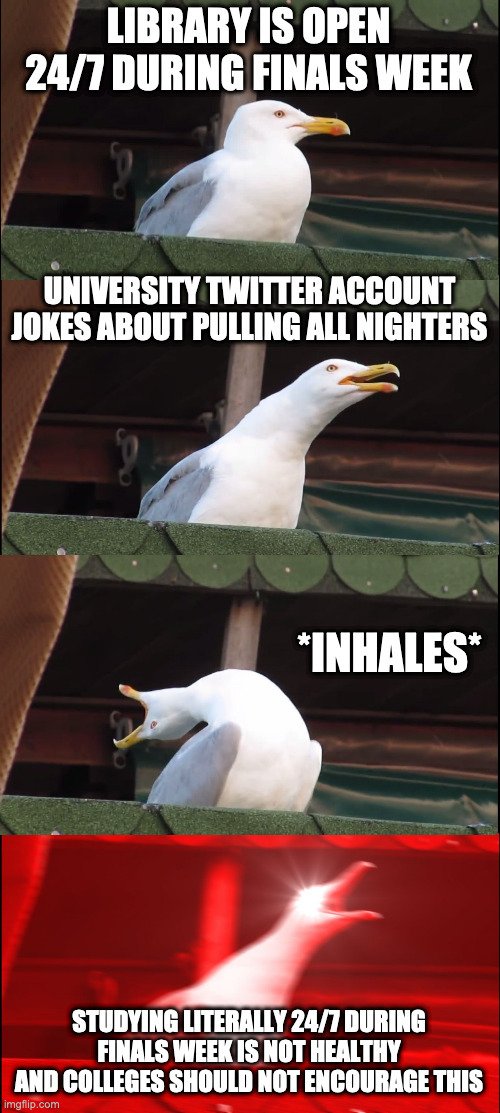

Students also demonstrated their understanding of the role of engaging emotional reactions in the texts they composed. Many students articulated an understanding of specific emotions in audiences that could be engaged through their texts. Specifically, students viewed the humor and the collective frustrations of audiences as something they should engage. Many students composed texts that contained multiple exclamation points, made referential jokes, and enacted rhetorics of frustration, anger, and/or disappointment. One student, Kacy, created this meme:

Figure 2: Meme a student composed about the rhetorics around finals week.

The meme engages with a then-current issue—the student texts were created two weeks before finals—and uses the multimodal affordances of memes to express outrage about one of the public rhetorics on the issue. Kacy then elaborated upon her decisions in her reflection on the tweet, explaining that, “I would post these on Twitter, because that’s where I find most student content circulates. In my experience, students take to Twitter to complain.” Kacy engaged both with a specific social media platform that she believed that her target audience used and with the emotions that she saw her target audience enacting on that platform. She observed and then engaged the seemingly common audience reaction of complaining about an issue.

Another student, Dan, attempted to use humor to generate circulation for his texts about the parking issues on campus. Dan created this text for Instagram:

Figure 3: A student’s Instagram post joking about campus parking issues.

Dan makes a visual joke about the parking issues on campus. He jokes that any additional parking, even in someone’s driveway, would be an improvement to the available campus parking. In both examples, the students engaged their audience’s perceived collective frustrations around an issue. Furthermore, the students sought to aggravate those emotions to provoke their audience into circulating their text. Most students wrote with and/or about what they believed to be the existing emotional perspectives on issues held by their audience. They engaged those perspectives either through humor or a position of collective outrage.

Along those lines, these students conflated their beliefs about the role of humor and outrage in virality into a single belief about the primary drivers of virality. The students viewed outrage and humor as the two ends of the same audience reactions that drove virality. These students believed extreme audience emotions, be they rooted in humor or anger, to be crucial in driving virality, but the students did not distinguish between the two. This suggests an important gap in the current circulation pedagogies, affect and the effects of emotion in circulation. Students are seemingly aware of the role of audience emotions in driving circulation, yet none of current pedagogies engage with this, at least not directly. In teaching circulation, then, we must find ways to call attention to and critically examine audience emotions and how some can be harmful, as Jonathan Bradshaw establishes in Rhetorical Exhaustion.

Put differently, the students possessed a sense of the importance of engaging “publics” and the existing rhetorics circulating within those “publics” to generate circulation (Edbauer; Matthieu and George). Yet the students believed publics to be a static audience that could only be engaged through a limited set of rhetorics. They believed that what drove virality within publics was participation in existing rhetorics and triggering the more extreme emotions connected to those rhetorics. For these students, the possibilities for virality’s effects on publics were narrow. Publics were impacted through the aggravation of collective emotions around a particular issue. Virality developed through the reinforcing of and exacerbating of existing rhetorics and the extreme emotions connected to those rhetorics. Many of these students had no understanding of the broader possibilities for and effects of circulation within publics. This suggests something critical about circulation pedagogies that many of the current pedagogies already point toward: students should compose for circulation (Bergstrom; Gries; Ridolfo and DeVoss; Warren-Riley and Verzosa Hurley). However, students should also compose for a variety of forms of circulation and for a variety of effects. Some of the current pedagogies implicitly engage with this idea, particularly Laurie E. Gries’ approach to teaching circulating. However, there is a clear need for having students compose for several forms of circulation and to then think about the different effects and affects that circulation will generate.

In sum, circulation has become a part of many students’ writing literacies, but the practices for and beliefs about circulation that have become a part of those literacies are limited. Many students understand circulation to be virality and only virality. As others have articulated, this leads many students to over-value social media metrics (Wuebben) while also developing anxieties about writing for those metrics (Gold et al.). My study furthers these points, establishing how virality has become a part of how students write, value the act of writing, strategize writing, and understand audiences and publics. This means that circulation has become a part of many students’ writing literacies before they enter composition courses. As my case study has suggested, many of the studied students had already developed a sense of some of the key aspects of existing circulation pedagogies, such as composing strategies for circulation and the importance of engaging the rhetorical values of an audience or public. All of this demonstrates that composition students would likely benefit from more complex, critical, and multi-dimensional engagements with circulation, engagements that build upon and critically examine students’ existing writing literacies.

“Circulation Just Affects Everything”

Many composition students already have experience with circulation. They have likely encountered it on social media or are at least aware of its most common form on social media, virality. As Aiden put it in his interview, “Circulation just affects everything. And circulation will always be there, whether you want it to be there or not.” This suggests a significant shift for how composition pedagogies should approach circulation. Circulation should be situated as an essential and prior element of students’ writing literacies.

As my case study demonstrated, students’ experiences with circulation, specifically virality, have influenced how they understand audiences, how they think about their own writing processes, and how they understand the possibilities for writing. Instructors should thus engage circulation as a pre-existing aspect of students’ writing literacies. Students’ experiences with virality should be acknowledged, incorporated into courses, and then connected to larger conceptions of circulation. While many students have some prior knowledge of circulation, they also have limited understanding of the rhetorical concept. Circulation should be approached as a rhetorical concept like audience and the writing process, as a concept that students have some prior knowledge of (Yancey et al.). Much like most students need with their understandings of audience and the writing process, students need opportunities to engage and expand their practices for and beliefs about circulation.

Enabling composition students to expand their practices for and beliefs about circulation requires only a few minor additions to composition courses. First and foremost, students need opportunities to share and make knowledge out of their experiences with circulation. As part of this, students should be guided to make connections between their knowledge about circulation and other aspects of writing. Second, students should be taught a more expansive definition of circulation. Put differently, students should be provided a broad definition of circulation so that they can situate their prior knowledge of circulation within. Third, students should get opportunities to compose for forms of circulation other than viral circulation. Students should get the opportunity to experience composing for circulation in forms other than virality.

One of the most important findings from my case study is that students have prior practices for and beliefs about circulation that are shaping their writing literacies, and thus students need opportunities in composition courses to share those practices and beliefs. Students need opportunities to discuss what they know, do, and experience with regards to circulation. Instructors should create opportunities for students to share what they already know and/or have experienced about circulation. More to the point, composition instructors need to create opportunities for valuing and discussing virality. It might be difficult to directly engage students’ experiences with social media, rapid online circulation, and other forms of writing that seem counter to academic writing (Wuebben). Yet, virality has become a part of most students writing literacies. Many students have practices for and beliefs about virality. They understand what it is, how to compose for it, and what causes it in public. Thus, composition instructors need to enable students to articulate virality as part of their pre-existing writing literacies.

Equally as important, students should connect their practices for and beliefs about virality to writing they do in the course. Students should be provided opportunities to share their practices for circulation and then apply those practices to writing they are doing in the course. In doing so, instructors can validate the aspects of students’ writing literacies that have been shaped by circulation and set up students to start growing those literacies. Doing so could take a range of forms. Students could do projects in which they write texts that they believe can go viral, enacting their practices and beliefs. Students could also do smaller projects, such as a revision workshop in which students share their practices for writing for virality and then use those practices to help them re-see and revise their work. Students need opportunities to share what they know about virality, and they need to have that knowledge validated in composition courses. Without such opportunities, composition courses risk creating a division between the writing literacies students learn and develop in composition courses versus what they have developed and enacted outside of them. This is particularly worrisome given the more troublesome aspects of virality that many students understand and have embraced as part of their understanding of writing, such as writing for virality involving provoking publics to generate social media metrics.

To expand students’ potentially worrisome practices for and beliefs about virality and thus their own writing literacies, composition instructors should introduce complex definitions of circulation. When many composition instructors teach audience, they find ways for students to share what they already know and discuss about the concept; for example, how many students understand the need to write differently when writing for friends versus family members versus teachers. Following this sharing, composition instructors introduce more complex ways to think about audience, for example, concepts of the rhetorical situation or discourse communities. Composition instructors need to develop similar approaches for teaching circulation.

While there are multiple ways to define circulation, my case study demonstrates that composition instructors should define the rhetorical concept in a way that clearly demarks the different speeds, effects, and audiences that circulation can have. Specifically, composition instructors should find ways to define circulation in a way that clearly distinguishes viral circulation from other, slower forms of circulation. Students already possess a focused set of practices for and beliefs about virality, which in turn have influenced their writing literacies. Expanding students’ practices for and beliefs about virality, thus, requires a more expansive understanding of circulation. It requires a broader horizon for circulation beyond accumulating social media metrics by provoking audiences through limited rhetorical appeals. To expand those practices and beliefs, composition instructors need to offer broader ways of understanding, experiencing, and, most of all, composing for circulation. Composition students need a sense that circulation can be much slower and have very different effects on audiences and publics (Bradshaw, Slow Circulation). More to the point, composition students need an understanding that there are slower forms of circulation that they can and likely already do compose toward.

Finally, composition instructors need to develop ways for students to compose for non-viral forms of circulation during class. Students need a sense of how, when, where, and why they and others compose for non-viral forms of circulation. Having students compose for non-viral forms of circulation could involve larger projects, much like the one detailed earlier in this essay. Students could deliberately compose for slow circulation, composing texts such as posters or essays that attempt to impact specific publics. However, students already regularly compose for slow circulation in composition courses: students already compose essays that circulate to their instructors and back to them. Thus, another option would be to have students consider and then compose the typical writing they do in composition courses through the framework of slow circulation. Students could think about how the writing they do in composition courses is a much slower form of circulation. Students could reflect upon this and be asked to think about how the real, and potential, circulation of their writing shapes how they compose. They could even consider how the audience of instructor and themselves is radically different from the massive publics many students understand as crucial to virality. The key would be for students to compose something toward a slower form of circulation. By composing for a slower form of circulation, students can have a broader, more complex understanding of circulation and, in turn, develop a broader understanding of their own writing literacies.

Circulation should be a part of all composition courses, either as a focal element or as one of many important aspects of writing that students learn about (Yancey et al.). Future pedagogical engagements with circulation should endeavor to expand how students understand the concept. These pedagogical engagements must engage with virality, situating it as one form of circulation among others. Key in these pedagogical engagements is valuing and expanding students’ practices for and beliefs about circulation, particularly their sense of virality. Without such pedagogical engagements, many students might continue to view circulation as virality. Such a perspective will likely lead many students to view circulation as the rhetorical process of provoking digital audience members to spread texts for the goal of amassing social-media metrics. Given both the risks of virality (Bradshaw, “Rhetorical Exhaustion”; Powers) and the goal of making students more critical and advanced writers (Yancey et al; Warren-Riley and Verzosa Hurley), this seems like a less than desirable outcome. Circulation needs to be taught in composition courses, and to teach it, composition instructors need to engage and build upon students’ prior experiences with circulation.

Notes

[1] The title is taken from a comment from a student whose work was studied in this essay. The student is explaining the composing decisions they made for a text they wrote and their ideas about why those decisions would generate circulation for the text.

Works Cited

Bergstrom, Tait. Remediation that Delivers: Incorporating Attention to Delivery into Transmodal-Translingual Approaches to Composition. Composition Forum, vol. 46, 2021.

Bradshaw, Jonathan L. Rhetorical Exhaustion & the Ethics of Amplification. Computers and Composition, vol. 56, 2020, doi:10.1016/j.compcom.2020.102568.

———. Slow Circulation: The Ethics of Speed and Rhetorical Persistence. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 48, no. 5, 2018. pp. 479-498.

Charmaz, Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory: A Practical Guide Through Qualitative Analysis. SAGE Publications, 2006.

Edbauer, Jenny. Unframing Models of Public Distribution: Rhetorical Situation to Rhetorical Ecologies. Rhetoric Society Quarterly, vol. 35, no. 5, 2005, pp. 5-24.

Gold, David, Merideth Garcia, and Anna V. Knutson. Going Public in the Age of Digital Anxiety: How Students Negotiate the Topoi of Online Writing Environments. Composition Forum, vol. 41, 2019. https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/41/going-public.php.

Gries, Laurie E. Writing to Assemble Publics: Making Writing Activate, Making Writing Matter. College Composition and Communication, vol. 70, no. 3, 2019, pp. 327-355.

Mathieu, Paula, and Diane George. Not Going It Alone: Public Writing, Independent Media, and the Circulation of Advocacy. College Composition and Communication, vol. 61, no. 1, 2009, pp. 130-149.

Powers, Devon. First! Cultural Circulation in the Age of Recursivity. New Media and Society, vol. 19, no. 2, 2017, pp. 165-180.

Ridolfo, Jim, and Danielle Nicole DeVoss. Composing for Recomposition: Rhetorical Velocity and Delivery. Kairos, vol. 13, no. 2, 2009.

Trimbur, John. Composition and the Circulation of Writing. College Composition and Communication, vol. 52, no. 2, 2000, pp. 188-219.

Warren-Riley, Sarah, and Elise Verzosa Hurley. Multimodal Pedagogical Approaches to Public Writing: Digital Media Advocacy and Mundane Texts. Composition Forum, vol. 36, 2017. https://www.compositionforum.com/issue/36/multimodal.php.

Wuebben, Daniel. Getting Likes, Going Viral, and the Intersections Between Popularity Metrics and Digital Composition. Computers and Composition, vol. 42, no. 1, 2016, pp. 66-79.

Yancey, Kathleen Blake. Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak. Writing Across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. Utah State UP, 2014.

Era of Virality from Composition Forum 52 (Fall 2023)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/era-of-virality.php

© Copyright 2023 John Silvestro.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 52 table of contents.