Composition Forum 52, Fall 2023

http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/

Playing with Mêtis, or, Cultivating Cunning in the Composition Classroom

Abstract: Responding to the call for embracing mêtis in the classroom, this piece puts scholarship on embodiment and emergent gameplay in conversation with one another to explore a potential means of cultivating mêtic intelligence in the composition classroom by empirically examining how the open world game The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (BOTW) scaffolds mêtic intelligence and encourages mêtic strategies in its players. Founded in Jay Dolmage’s understanding of mêtis as a means to turn the tables on those with greater bie (brute strength) and Karen Kopelson’s use of mêtis as a means of subtle resistance, this piece takes a mixed methods approach and utilizes interview data to see what design elements of BOTW may be able to be brought into composition course design to help cultivate cunning in our students both inside and beyond the classroom.

In his 2009 essay Metis, Mêtis, Mestiza, Medusa: Rhetorical Bodies across Rhetorical Traditions, Jay Dolmage unearths Metis, the Greek Goddess of wisdom, to argue for “new rhetorical possibilities for an alternative, embodied tradition to create rhetorical exigence for bodies that have been overlooked and Othered” (2). His approach of re-membering rhetoric’s past through the unburying of Metis as a rhetorical principle combined with his calling on rhetoric to make itself accessible to those who write from the margins offers writing instructors an important tool for empowering writers by garnering their mêtic intelligence. It is through this particular rhetorical concept, then, that we as writing instructors can cultivate Metis’ cunning in our students to help them become agents of change. But mêtis, due to its internal nature, is a difficult rhetorical concept to see in action, let alone scaffold into a classroom. As such, this article not only positions mêtis as a particularly useful rhetorical tool in the writing classroom but also traces one potential method for garnering mêtic intelligence through the use of open world games as exemplified by an IRB-approved case study.

As it currently stands, few scholars have offered mêtic approaches to the teaching of writing. Those that have offer up mêtis as a potential framework for analysis (McDermott), or explore how mêtis can be applied to elicit a desired effect or student response (Atwill; Kopelson 115). Furthermore, even with a handful of scholars arguing for mêtis in the classroom, few if any scholars have offered suggestions as to how to actually cultivate mêtic strategies in students, though some scholars such as Ann Brady and Rebecca Pope-Ruark offer methods for bringing mêtis to students’ attention. However, neither of these authors explore how to actually cultivate or develop students’ mêtic intelligence or provide them with strategies they might use to develop their mêtis on their own, despite both authors admitting that these strategies would greatly improve students’ problem-solving skills (Brady 225; Pope-Ruark 335). To address this, the current piece expands the examination of mêtis in writing and composition studies by articulating various means of encouraging mêtis through an empirical case study of how video games, specifically open world games, cultivate this kind of cunning in their players. Because open world games provide a particularly visible means of how to scaffold tasks in ways that build mêtic intelligence, this piece uses a mixed methods approach to posit how composition instructors might mirror such strategies in our classrooms to build this particularly useful rhetorical skill in our students.

Relying first on Dolmage and then expanding his understanding through Kopelson as a foundation for understanding mêtis as more than simple trickery, I first situate mêtis within writing studies. I then position mêtis as an embodied act in order to explain how and why video games not only provide one avenue of seeing mêtis in action, but also allow for the cultivation of mêtic intelligence. In particular, the current project examines this process by relying on an empirical case study using Nintendo’s Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (BOTW). Finally, based on the results of this study, the piece ends by describing the kinds of pedagogical practices we might be able to bring into the writing classroom in order to help cultivate this particular kind of cunning in our students, so that they may learn to “see the world slightly differently,” and potentially “find opportunity to turn the tables on those with greater bie, or brute strength, than they have access to” (Dolmage 9).

Mêtis and Writing Studies

Often disregarded for its association with trickery and deception, mêtis as a rhetorical concept is often reduced to a synonym for adaptability (Detienne and Vernant). It is perhaps for this reason that despite writing studies’ embrace of similar rhetorical strategies such as techne and phronesis, mêtis has not received much scholarly attention in our field. Furthermore, even when writing studies calls for a mêtic approach, due to the difficulty in seeing or measuring mêtis, these calls rarely if ever include a means for cultivating said strategies in the classroom. However, mêtis is particularly useful for the writing classroom, as arguably one of our main goals as writing instructors is to teach students strategies for acting and reacting deliberately in and across various rhetorical situations.

In her 2003 essay, Karen Kopelson begins her argument with the premise that “composition’s ‘critical pedagogies’ fail to meet the challenges posed by today’s specific formations of student resistance and that they fail particularly, and most ironically, because of their inattention to differences among classroom rhetorical contexts” (118). Teaching our students to think in such ways, much like Kopelson notes, relies on mêtis in order to produce a pedagogy that brings specific attention to these different rhetorical contexts by conceptualizing each individual classroom as its own proceduralized system, with its own constraints and affordances, as well as implicit and explicit arguments and procedures. In other words, mêtic pedagogies allow for classrooms to exist as their own individual possibility spaces (Bogost) in order to permit the kinds of difference Kopelson argues often go overlooked. A key part in illuminating these differences, then, is utilizing one’s mêtic intelligence to “see the world slightly differently,” (Dolmage 9) not only to help navigate student resistance, but also to develop students as individual agents of change. For both Dolmage and Kopelson, then, mêtis is more than simple trickery or adaptability: it is a deliberate enactment of a particular strategy responding to a particular context.

Though Kopelson’s article revolves specifically around strategies to use student resistance productively, the goals she asserts for instructors using this method reflect some of the central learning outcomes we want to cultivate in our writing classrooms. For example, she encourages instructors to perform a neutrality that is “deliberate, reflective, [and] self-conscious,” (Kopelson 123), all general habits we want to encourage and develop in novice writers. Further, because of the reliance on a type of “trickery” to accomplish this goal, Kopelson establishes mêtis as the best rhetorical strategy available, advocating mêtis as “reflective, goal oriented, and decidedly serious in its play” (134). That said, despite positing that writing instructors add mêtis to their teaching arsenal, Kopelson’s piece does not really offer a means for doing so. In addition, Kopelson focuses on how mêtis benefits instructors, when it is clear that students would also benefit from this rhetorical strategy in their writing, often for the exact same reasons she argues mêtic pedagogies empower instructors. Thus, while Kopelson makes the case for bringing mêtis into the writing classroom, she does not provide a means of teaching mêtis or mêtic strategies to her students. Rather, we need to turn to other scholars to see how mêtis has been brought into the classroom as a rhetorical strategy to pass on to our students, so they too may enact this strategy purposely and deliberately, rather than by chance or accident.

In her article A Case for mêtic Intelligence in Technical and Professional Communication Programs, Rebecca Pope-Ruark argues for the pedagogical application of mêtic intelligence in technical and professional communication programs. Describing mêtis as a “flexible, innovative intelligence used in unexpected or unprecedented situations” (Pope-Ruark 323), she argues that technical and professional communications programs in particular should strive to cultivate mêtic intelligence in their classrooms through the use of client-centered service learning initiatives. Relying on Dolmage’s revisioning of the myth, Pope-Ruark argues mêtis as “a complement to phronesis” and “a necessary intelligence to enact prudent deliberation and to balance creativity with socially appropriate responses to particular situations” (327). In other words, Pope-Ruark positions mêtis as a form of rhetoric, and in particular, a rhetorical approach that allows for flexibility and individualized responses to particular audiences in particular contexts. Here, mêtis serves not only as a tool for writing instructors, but as a rhetorical strategy necessary to teach to our students for their benefit, and yet again we see that mêtis is more than just a reaction to a situation: it is a deliberate execution of a particular strategy within a particular context, even if that context is unexpected and/or unpredictable.

Put simply, despite the limited amount of literature positioning mêtis in writing studies, our classrooms often must apply and cultivate the very type of rhetorical awareness, intent, and flexibility mêtis requires. Furthermore, both Kopelson and Pope-Ruark allude to the fact that mêtis is often already present in our classrooms, albeit usually an implied one due to the difficulty of seeing mêtis in action. However, while Dolmage, Kopelson, and Pope-Ruark all point to mêtis as cunning, adaptive, and flexible, none of these authors delve into how to practice mêtis as a rhetorical strategy. That is, despite arguing for the merits of mêtis, few if any writing studies scholars have traced how to tap into mêtis in ways that help develop it as a rhetorical skill, which could be because of mêtis’ more innate, or embodied, role: much like writing, mêtis must be practiced to be mastered. To help our students learn and benefit from this particular rhetorical appeal, then, we must not only find ways to visualize and assess mêtic intelligence, but we must also design our classrooms in ways that allow students the kind of exploratory and experimental experiences mêtic intelligence requires as a repeated, embodied skill.

Mêtis, Embodiment, and Game Studies

Relying on Debra Hawhee’s Bodily Arts, Dolmage ultimately argues that mêtis, and thus rhetoric, is an embodied act. According to Hawhee, “thought does not happen within the body, it happens as the body” (58). This provides another example of how mêtic concepts already infiltrate our composition classrooms, as the idea of writing as an embodied act receives frequent attention in composition research, though it should be noted that mêtis is its own special state of embodiment. A recent study on student perceptions of “doneness” in the composition classroom, for example, illustrates this sort of embodiment, as McAlear and Pedretti found that students most often relied on some inner sense of affective judgment to determine when their assignment was “done” (72). As they noted, the idea of “doneness,” especially for novice writers, marks “a substantive difference between an institutional or external marker of doneness and a personal, internal one” (77). In other words, without the marker of an external deadline, students’ sense of when a paper is finished seems to rely more on an internal understanding or feeling of completeness, reflecting the idea of writing as an embodied act. Further, they note in their results that when revising, “first-year students privileged clarity and proofreading, while second-year students privileged meeting the criteria and clarity” (84) to assess the “doneness” of their particular paper. Here, we see mêtic intelligence in that the second-year students have learned through their previous experiences what their instructors are more likely to value and adjusted their revisions accordingly. Even this shift from first-year to second-year priorities reflects the development of mêtis in the classroom, as the more students write and the more they become aware of their writing practices as embodied rhetorics, the stronger their ability to adapt and respond to particular needs and criteria becomes.

Associated with cunning and one's ability to respond to unexpected situations, previously mêtis was often reduced to a synonym for flexibility and/or being able to adapt (Detienne and Vernant). However, what this definition fails to account for is the combination of forces, both conscious and unconscious, that come together to form mêtis as an embodied act. As argued by Hawhee, because rhetoric was “an activity,” (15) rhetorical strategies such as mêtis must be understood as both a mental and physical performance. Rather than merely the ability to navigate and manage unprecedented or unfamiliar situations and outcomes, mêtis instead requires both a proactive and reactive ability to respond to these new contexts in a particular way, through both the body and mind, the conscious and the unconscious. Synthesizing Dolmage, Hawhee, Kopelson, and Pope-Ruark’s definitions of mêtis, then, for the purposes of this study I explicitly define mêtis as a deliberate rhetorical response where habits inform strategic reactions to particular rhetorical situations based on previous embodied dispositions.

Aligning mêtis with habit often brings the same misconceptions with hexis: as embodied acts, on the surface, it would appear that mêtis is either a natural talent, or something that occurs by luck. However, much like hexis, mêtis allows for a reimagining of a situation in order to overcome those with easier access to power and privilege than one may have access to themselves. In fact, as Phill Alexander points out with regard to phronesis and techne (both areas of virtue related to mêtis), “these knowledges are about being practiced; they come into existence through use and are conducted through use” (4, emphasis in original). That is, rather than a lucky break or a natural disposition, mêtis requires practice just like any other virtue, with each instance of use lending to its overall strength. That said, mêtis’ strength comes from its ability to “see the world slightly differently” and finding the “opportunity to turn the tables on those with greater bie, or brute strength, than they have access to” (Dolmage 9), which is one of the reasons why the term has been historically associated with “trickery,” and more explicitly negative, “empty rhetoric” (Detienne and Vernant 45). In addition, as the term is often associated with women and disability (Dolmage 2), it carries additional negative connotations, despite its original position as a virtue.[1] However, as argued in Ash’s Technologies of Captivation, no action is completely tacit; rather, actions are an interplay between conscious or deliberate action and internal, tacit reaction. mêtis, then, is both a practiced, conscious effort as well as an ingrained, subconscious habit. As such, scholars seeking to observe mêtic strategies must also address its embodied nature, and one place to do so is through video games.

Expanding on the above conceptions of embodiment, not only does thought happen as the body, but so too does writing, and, as Dolmage, Kopelson, and others argue, this fact illustrates that mêtis always resides in our classrooms, albeit perhaps in the same sort of blackbox that obscures other aspects of our courses as well.[2] In a similar sense, current work intersecting game studies and writing also positions the act of playing a video game as participating in an embodied argument (Shultz Colby 55). Expanding on works such as Ian Bogost’s The Rhetoric of Video Games and James Paul Gee’s Good Video Games and Good Learning, other scholars have also noted the power of embodiment in video games in particular. Steve Holmes, for example, examines how embodiment works with regard to habit in Procedural Habits, and my own chapter in the edited collection The Ethics of Playing, Researching, & Teaching Games in the Writing Classroom illustrates how the habits reinforced through playing a game can sometimes even change a player’s disposition (Caravella). Similar to writing, then, some amount of mêtis tends to also reside in video games in some way. More importantly, because the act of playing a video game often includes a visual means of representing the usually hidden or blackboxed problem solving processes involved, video games can help us see mêtic intelligence and strategies in ways that other approaches cannot, and as I will argue in the next section, open world games in particular seem to be especially useful for this process. Drawing on gameful design (McGonigal) and using open world games as a starting point, then, we can begin to pull mêtis into the light, making it a skill we can help our students develop and practice in the writing classroom. Rather than merely teaching them to be more “flexible,” in that writing calls attention to the need to better assess rhetorical situations to be effective, mêtic classrooms provide students more opportunity to learn how to better meet the expectations of certain instructors and assignments, and how to deliberately act on these contexts in order to accomplish their own personal and individual writing goals.

Visualizing Mêtis through Open World Games

Defined broadly as a genre of video game that allows players to freely explore and complete objectives, open world games are most known for their break from the traditional linear-style of gameplay. Where some games follow a strict scaffolding (level 1 progresses to level 2 and so forth), open world games often allow players to explore at their own pace and according to their own wants/goals. Open world games, through their reliance on emergent gameplay, can help make the intersections between explicit and implicit responses more visible, as these games require the kind of deliberate, adaptive intent in order to make progress, while simultaneously offering opportunities for players to practice these responses until they become habit. In other words, emergent gameplay refers to the unique and often complex situations that arise in video games due to the interactions of relatively simple game mechanics.. Because they do not follow a linear structure, open world games rely on emergent gameplay to structure the player’s experience, as unlike a linear reward system, players in an open world game may or may not have acquired specific materials or abilities to complete a given area of the game. While this may make certain areas of the game more difficult, in a well-designed open world game, this would not necessarily bar the player from completing that particular section. Rather, through emergent gameplay, players could potentially overcome even the final boss of a game without playing through the other parts of the game, as is the case with various speed runs one can watch on YouTube. Finally, despite the vastness of open world games, as a genre they tend to include similar elements, such as level trees which allow players to specialize in certain styles of play as they gain experience, collecting a vast number of resources across the map, and often also include a crafting system that allows players to use said resources to their advantage. Thus, despite being an entirely new type of emergent gameplay, many gamers can move smoothly between one open world game to another once they learn the basic move set involved in the emergent gameplay loop.

As noted by Alexander in KNOWing How to Play, gamers rely on both latent and active knowledge types when playing a game, with latent knowledges referring to what players already know or have previously established as unconscious habit and knowledge “laying in wait” inside of a material (or in this case, virtual) object, and active encapsulating what players have been explicitly taught, phronetic knowledge, and epiphany. It is the combination of these knowledges that culminate into mêtis, as players must rely on both their previous knowledge and established habits (or in other words, their unconscious knowledges) and their active ones (or, conscious knowledges) to overcome a game’s challenges. In fact, Alexander notes that his conception of elastic/kinetic knowledge, which he initially links with phronesis, is “a type of knowledge similar to mêtis in many respects, in that it can appear as a ‘flash.’ It’s an ability to problem solve based on previous experiences and skills” (8). Though he does not refer to mêtis explicitly, Alexander pinpoints how emergent gameplay can help players practice (and thus increase their own) mêtic intelligence, as gamers rely on this “flexible, problem-solving knowledge, based on reacting and exploring” to overcome obstacles and make progress. That is, open world games provide a space where we can actively, explicitly see a player’s use of cunning (both the conscious and unconscious aspects) and how they use it to overcome challenges, especially those where they would have been otherwise outmatched had they attempted a more traditional hack and slash or brute force method.

In terms of cultivating cunning in our students, understanding how open world games accomplish this in their players provides a starting point, with the ultimate goal of developing students’ mêtic intelligence so that they might utilize such cunning in rhetorically purposeful ways both in our classrooms and beyond. By rewarding players who use strategies other than brute force to overcome obstacles and providing repetitive visual cues to help these strategies become ingrained over time, open world games in particular provide key design elements to help players develop their mêtic intelligence, and such designs can be brought into our pedagogy. As such, using these games to observe and assess how gameful design provokes the kind of deliberate cunning mêtis requires, we can then translate these elements into our course design in order to help our students both see and embrace their own mêtic tendencies, especially in cases where students may not be in a position of power with relation to the issue they want to impact.

Measuring Mêtis in Breath of the Wild

Because of their reliance on emergent gameplay and their rejection of linear structure, open world games and the vast possibility spaces (Bogost) they provide purposefully positions players so that they must use cunning and/or wit to overcome obstacles and make progress in the game. In particular, Nintendo’s 2017 release, The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild (BOTW), released on both the WiiU and Nintendo Switch, relies heavily on a player’s mêtic intelligence and deliberate strategizing to solve puzzles, defeat enemies, complete quests, explore the world, collect objectives, and eventually, defeat the final boss. Exemplifying the core principles of open world right from the start, BOTW begins with the player character, Link, awakening in a cave with no armor or weapons. Upon leaving the cave and entering the world, players pick up whatever they can (sticks, pot lids, etc) to defend themselves from enemies and start exploring to find new gear along the way. While the first area of the game technically serves as a tutorial which awards Link his basic moves upon completion, even this section remains optional, with players finding multiple ways to leave the tutorial zone without completing all its tasks or gaining all its rewards. Winning 163 total Game of the Year awards and positioned by many video game journalists as one of the greatest open world video games of all time (Weidner2017) BOTW exemplifies the unstructured, adaptive, and exploratory nature of open world games from start to finish. As such, it provides a particularly useful space to observe mêtic intelligence in action, through its constant and consistent implementation of emergent gameplay.

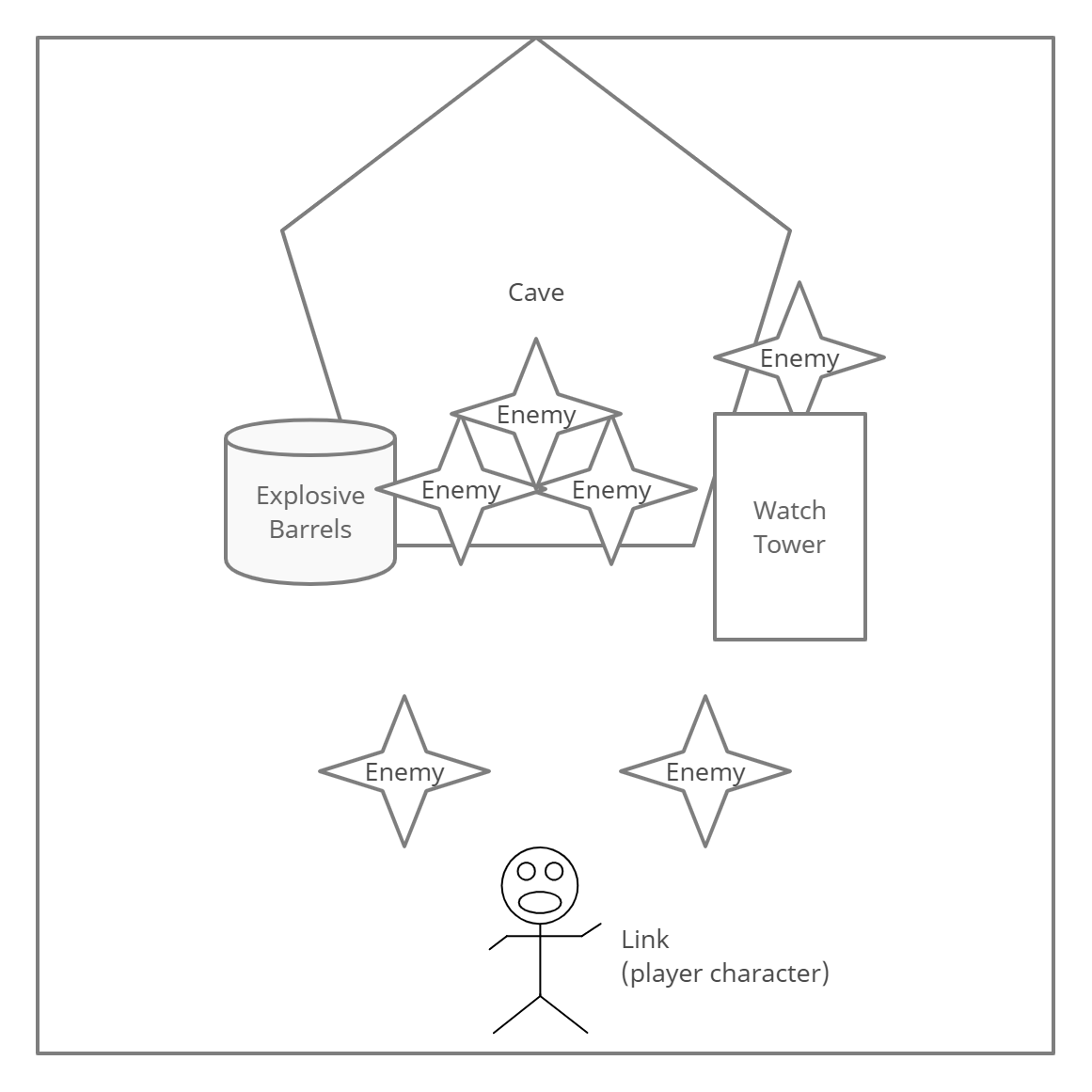

As previously noted when defining emergent gameplay, due to their lack of structure, clear boundaries between levels, and the emphasis of player choice, open world games must operate in a way that allows them to be played in a myriad of different ways. For example, the figure below illustrates the layout of a typical battle encounter found within BOTW. As shown by the image, Link is surrounded by multiple enemies, which happens from the very beginning of the game even though the player starts with no gear and must find their own weapons. However, even in this instance, the player has a plethora of options and simple game mechanics to defeat these enemies, despite being outnumbered and substantially weaker than their opponents. For instance, using the bomb function within the game, the player can quickly dispose of multiple enemies by throwing a bomb to the left side of the cave, where additional explosive barrels are visible. Such an explosion would quickly dispose of any enemies lurking within the cave. However, this strategy risks missing the two enemies beside Link, as well as the lookout positioned on the tower to the right, who will alert other enemies in the area if left alive.

Figure 1. Typical Enemy Positions in BOTW

Should the explosion reach too far or Link moves too close when aiming his bomb through, he will also be hit, killing not only his enemies, but the player character as well. The player also has the option to try to fight back with their equipped weapon, but it would prove difficult for an unskilled player to fight using brute strength alone in this instance, since the equipped weapon is merely a wooden club with relatively low attack stats. Through these visual cues, it is the actual design of the environment itself (as opposed to any equipment or mechanics) that intentionally positions and encourages players to use cunning rather than brute force or the most obvious strategy to overcome obstacles and/or enemies.

In addition to encouraging use of the environment, mechanics and equipment also play a role in building players’ mêtic intelligence. Players have the option to wield a bow with multiple types of arrows, for example, allowing them to do more damage depending on the situation. Rather than throwing a bomb at the explosive barrels, for instance, Link could shoot a flaming arrow there instead, disposing of the enemies within the skull cave without having to turn his back on the three outside of the cave or risking getting too close to the explosion and suffering damage himself. In addition, Link is also able to light his club on fire with such a strategy, or he could focus on a single enemy and then take their weapon after he defeats it. Finally, Link could also choose to eat some prepared food made through the game’s cooking mechanisms, any of which could help increase his strength, health, damage output, evasion, or otherwise. In short, BOTW provides almost an infinite of ways to overcome obstacles within its possibility space, all of which rely on the game’s central fighting mechanics, but require the player to respond in complex ways that cannot be predicted: there are multiple skull caves such as this found in the game, and no set way that is better or a general approach that would work in most instances for this particular encounter. Rather, the player must consistently and quickly assess the individual contexts of each particular battle instance and use the environment and simpler game mechanics to build more complex strategies and defeat such enemies.

By designing their game to rely on emergent gameplay, BOTW requires mêtis to overcome obstacles, not only forcing players to execute such strategies in order to progress the game, but also requiring them to practice, develop, and adapt these strategies as the game becomes more difficult and produces more and more challenging obstacles to overcome. Players’ reactions to such obstacles must be deliberate, and rarely can players rely on a brute force approach to overcome them. In other words, much like Aristotle’s virtue ethics as previously discussed, BOTW’s design uses both a reward system and repetitive visual cues to help establish a conscious response which then becomes habit as they progress through the game.

Despite being poorly equipped with little to no armor and a stick for defense in the above example,\CA the player must rely on mêtic emergent gameplay to come up with ways to defeat enemies stronger than them by using the core game mechanics available. BOTW, therefore, provides a method for researchers to observe mêtic intelligence and response, as well as a means to evaluate whether or not the response was effective, as if the player succeeds and defeats these enemies, they are rewarded by unlocking the chest visible within the cave, which most likely contains some kind of weapon upgrade or other useful materials. Conversely, if the player’s mêtic response is not clever enough to overcome their enemies, Link will die and respawn, giving them infinite chances to try alternate strategies. Thus, BOTW provides explicit instances where the player must intentionally and deliberately, but still relatively quickly, respond to and overcome obstacles (be they enemies or otherwise) through methods other than brute strength; in other words, BOTW provides clear instances where we can not only observe, but measure mêtic intelligence in action, as well assess the means through which the game design itself encourages such strategies from its players, providing a visible means for how we might bring these design elements into our pedagogy. In order to accomplish this, the mixed methods portion of the study relies on the following research questions:

- How do open world games cultivate and encourage mêtic intelligence and/o strategies in players?

- How can we transfer these design elements to the composition classroom?

Methods

There were a total of five participants for this IRB-approved case study, each with varying degrees of gaming literacy and previous experience playing BOTW, as illustrated in Table 4 below. Participants were recruited via a flier posted at a large research university and were not from a particular course, nor were they students of the principal investigator. Participants met with the investigator on campus for both parts of the data collection process, and all game materials and hardware were provided to them.

Data collection occurred in two parts. Upon arrival at the first meeting, participants signed the informed consent and filled out a brief questionnaire asking the number of hours they had previously played BOTW(0 hours, 5-10 hours, 10-20 hours, and 20+ hours) and where they would rate their gaming literacy, defined as “the ability to effectively navigate, interact with, and achieve goals in a gaming environment” (Dudeney, Hockly, and Pegrum 14), on a 1 (very low) to 10 (very high) scale. After completing this survey, participants were recorded playing BOTW for one hour. After reviewing the recordings, within one week of the first meeting, participants returned for a follow-up interview with regard to specific instances of their individual playthroughs categorized as mêtic. The number of mêtic instances that occurred during the hour of playtime was also recorded.

Relying on my expanded definition, gameplay was categorized as mêtic during instances of observable emergent gameplay where players were explicitly at a disadvantage in terms of “bie,” or brute strength, and had to use their wits and/or environment to overcome obstacles. In other words, gameplay was categorized as mêtic when players deliberately used cunning or trickery when attempting to defeat an enemy, solve a puzzle, or obtain a collectible, rather than relying on melee combat or other straightforward, strength-based approaches. For example, if players ran directly at an enemy and beat it simply by hitting it with their equipped weapon, the instance was recorded as “obstacle overcome,” but not as mêtic. If the participant instead snuck around an enemy, shot an arrow to draw the enemy towards an explosive barrel, and then released another arrow to set off the explosive barrel, the instance would be marked both as mêtic and as “obstacle overcome.” That said, because mêtis is a learned, experiential intelligence, players did not have to succeed in order for the attempt to be marked as mêtic; instances were recorded whether the player overcame the obstacle or not, meaning some of the instances observed were alternate strategies for the same obstacle. In short, this meant that gameplay recordings noted the total number of obstacles attempted (fighting enemies, attempting puzzles, or trying to obtain collectibles), the total number of obstacles overcome (defeating enemies, solving puzzles, and obtaining collectibles), and the number of mêtic instances observed, as detailed in the following table:

Table 1. Participant Gameplay Data

| Participant | Gaming Literacy Score (1-10) | Previous Experience Playing BOTW | Total number of Obstacles Attempted | Total number of Obstacles Overcome | Number of mêtic Instances Observed |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| A | 8 | 20+ hours | 22 | 18 | 12 |

| B | 6 | 20+ hours | 24 | 20 | 12 |

| C | 4 | 5-10 hours | 21 | 14 | 18 |

| D | 8 | 0 hours | 19 | 10 | 16 |

| E | 2 | 0 hours | 21 | 10 | 18 |

In addition to the above, a key part of the initial coding schema for recorded game play paid special attention to how players reacted when their strategies failed and they either had to try again or try a different tactic in order to measure not only where mêtis is visible in open world games such as BOTW, but also the kind of feedback systems such games implement to encourage and develop more efficient and/or effective mêtic strategies. To gauge this, while reviewing the recordings, I noted instances where players attempted and failed an obstacle so that I could play them back during the interview to obtain qualitative data as to why players made additional attempts. After the initial playthrough, participants responded to semi-structured interview questions about these instances. Participants were then asked to recall their thinking during these in order to confirm deliberate intent as well as examine how players perceive the game’s design influence on the strategies they used to overcome certain challenges. Though the number of instances varied depending on the participant, after being shown an example of their own recorded gameplay illustrating mêtic strategy, all participants were asked the following, depending on the instance in question:

- All instances: Can you explain the logic behind your strategy, or, what made you try to overcome this obstacle in this way?

- All instances: Have you overcome other obstacles in this game in a similar way? Why or why not?

- If the attempt failed (or, the player did not obtain their objective, died, or otherwise did not overcome the obstacle): Why do you think you did not succeed here? Can you recall your feelings, at this moment? To what extent, if any, did this failure influence proceeding gameplay?

- If they tried the same obstacle again after failing: What in-game elements, if any, influenced your decision to try again? Did you alter your original strategy? Why or why not?

- If they moved on to another obstacle after failing: What in-game elements, if any, influenced your decision?

Questions one and two were aimed at examining the habitual nature of mêtis, as both questions attempted to explore how players’ previous experiences and gameplay habits (both with BOTW in particular and games more generally) influenced their responses to a given obstacle. In addition, these questions sought to pinpoint players’ reasoning for using more cunning strategies as opposed to merely “brute forcing,” (as would be the case with those relying on bie) or taking a “hack and slash” approach to defeating enemies or solving puzzles. The remaining three questions sought to explore players’ own assessment and reasoning for changes in strategy, connections with later play instances, and what sorts of in-game elements may have influenced these decisions. In this way, the interview questions aimed to examine mêtis by focusing on its role as the synthesis of wisdom and experience within the context of this particular video game, as well as provide some preliminary insights as to what design elements the game itself offered that allowed players to practice (and thus further cultivate) mêtic intelligence. Using a grounded theory approach, these interview results were then analyzed to uncover any repeated themes in participant responses.

Results

The three participants (C, D, & E) with less previous BOTW experience enacted more mêtic strategies than participants with more experience, with participant C, who had five to ten previous hours of play, enacting mêtis 18 times, and participants D and E, with no previous experience playing, enacting mêtis 16 and 18 times, respectively. In most cases, participants enacted mêtis when facing an opponent, rather than solving a puzzle, but this was most likely because enemy encounters are more frequent in BOTW than puzzle challenges. As such, most mêtic instances enacted cunning strategies when either outnumbered or otherwise at a disadvantage, such as when participant B opted to lead enemies to an area filled with water, then proceeded to launch themselves into the air to shoot an electric arrow below, defeating three enemies simultaneously due to the increased damage and area of effect allowed for by the environment. Though this player could have confronted these enemies one-on-one via land, this strategy not only offered less risk of failure, but also allowed the player to defeat all three enemies at once while still maintaining the ability to retreat if things went bad: “I wanted them down quick so I wouldn’t lose my weapon durability… this was the best option, especially since if I messed it up I could just run away.”[3]

In addition to the above example, mêtic strategies between new players and experienced players varied greatly. Despite enacting mêtis less often than their less experienced counterparts, participants A and B showed far more skill and intent in their cunning strategies than the less experienced players. For example, when facing a large number of mid-level enemies, participant A first went to another area of the game to collect Octo Balloons (dropped from a specific enemy, Octoroks; players can attach these items to others to make things like barrels and rafts float in the air) before returning to the original enemies. However, rather than facing these enemies directly, participant A first positioned himself across a small river from the collection of enemies. Here, he used a nearby raft to prepare his attack. Using Link’s “Square Bomb” ability, the player loaded a number of bombs onto the raft. Then, he attached four Octo Balloons to the raft, and (using another piece of equipment, a Korok Leaf, which creates gusts of air when swung), blew the bomb-ladened raft towards the enemies, detonating it when it was just above their camp. When asked why he went for a much more complex approach, participant A responded “I knew I wasn’t up to snuff to face them head on but I’ve done stuff with these [the Octo Balloons] before. Even if it failed, running away or sending another bomb is quicker than having to respawn and walk all the way back.”

Conversely, inexperienced players, though they enacted mêtis more frequently, relied on far less complex strategies, as they did not have the previous experience necessary to accomplish the same kinds of mêtic responses as the more experienced players. That is, the less experienced players relied more on environmental advantages gained by changing their directional approach with regard to enemies, rather than the complicated ambush method used by participant A above.

When asked why participants enacted a mêtic strategy rather than taking a more straightforward approach, the most common response was that the cunning strategy allowed them to overcome obstacles more quickly and with less risk of death, as noted in some of the responses below. That being said, the two players with more experience (participants A and B) also opted to use brute force approaches more readily than players with less experience, in that, despite the similar number of obstacles overcome between the two sets of participants (22-24 for Participants A and B and 19-21 for participants C D and E), not only did the two more experienced players succeed more often (18-20 times versus 10-14), they enacted mêtic strategies less often to do so (12 times versus 16-18). This is most likely because the game rewards previous mêtic strategies with increased stats and stronger weapons, so that as players get stronger, they require less cunning strategies to solve puzzles or defeat enemies. As noted by participant B in her interview, “At this point, it’s just faster for me to hit these guys in the face. I used to have to strategize, but now I’m strong enough to just beat them down.” Similarly, participant A also noted that he used mêtic strategies to defeat opponents “when [they] didn’t have to” because “there’s less risk to flip them into the water, just in case something goes wrong.” Across all participants, the reasoning given for utilizing mêtic strategies came back to mitigating risk and increasing efficiency: BOTW’s game design encourages mêtic practices by both rewarding strategies that rely on using the environment to one’s advantage and establishing time consuming, but not permanently damaging, risks should a brute force approach fail.

In addition to more experienced players’ ability to use brute force to overcome obstacles, newer players reported that they did not have the means to overcome obstacles via brute force, even if this had been their original strategy. For example, Participant D, who reported a relatively high degree of gaming literacy and had previously played other Legend of Zelda titles, assumed that, as in the previous titles, they would be able to defeat enemies with melee weapons, as is the norm in previous Legend of Zelda games. BOTW’s design, however, “basically forced [him] to try stuff besides just attacking head on, and only gives you a stick!” In this way, this participant had to alter their original strategy (which was to just run up to an enemy and try to smack it to death with said stick), as the enemy proved much stronger than anticipated. Rather than give up after death, though, Participant D instead used the in-game environment to their advantage, climbing a nearby rock surface so that he could ambush the enemy from above, doing more damage while simultaneously stunning the enemy to give them more time to do damage before the enemy could retaliate. Here, despite still ultimately relying on the stick as their only weapon, Participant D re-strategized based on their previous failure, relying on cunning rather than the original direct approach that resulted in failure.

Unlike previous titles, BOTW does not provide equipment at the start of the game, leaving the player character at a distinct disadvantage. However, as the game clearly seeks to develop mêtic habits in its players, by not providing players weapons strong enough to defeat enemies via brute force at the beginning of the game, it forces them to either find other means to defeat enemies, or run from them until they find a better weapon. In other words, from the very start of the game, BOTW forces its players to make deliberate choices that will eventually become habitual responses as they continue playing. As such, it makes sense that participants with less or no previous experience playing the game prior to the study enacted mêtic strategies more frequently than more experienced players.

Finally, in addition to rewarding mêtic strategies by providing stronger gear or increasing one’s speed in overcoming obstacles, BOTW’s most effective strategy for cultivating mêtis seems to lie in its visual cuing. Like most games, BOTW relies on visual, auditory, and textual cues to provide hints and other strategies for players to progress the game. However, across all five participants, visual cues seemed to be the most readily noticed and understood, rather than auditory or textual ones. For example, Participant C noted in his interview that the names of the smaller temple challenges in the game often provided clues or other guidance as to how to complete the puzzles inside: for example, the Kema Zoos Shrine is titled “A Delayed Puzzle,” and the solution requires the player use a “Stop Time” mechanic to progress.

In addition to the textual visual cues, BOTW utilizes a number of other visual cues as well, such as when metallic objects Link can move or otherwise interact with glow bright yellow when using his “Magnet” ability. Though these cues can be easily overlooked, by continuing to play the game and developing the habit of looking for such cues over time, players are able to complete puzzles and other challenges more quickly as they progress. However, despite their initial acknowledgement of the textual cues, when completing one of these challenges, it was observed that Participant C did not notice the name of the challenge, “A Delayed Puzzle,” and instead more readily noticed the visual cue given that would allow him to momentarily “pause” a particular object to unlock the adjoining room and complete the puzzle. When asked about this process in their interview, Participant C reported that “sometimes it’s just easier to look for the colors, especially when you’re lazy like me and don’t always like to read.” In other words, rather than utilizing all available cues the game provided, it seems that having multiple visual cues for the same mechanic may help cultivate mêtic strategies more than individual cues presented alone.

Pedagogical Implications & Study Limitations

Though the study above relies on responses from only five participants, these results can begin to help uncover aspects of mêtis that may be beneficial if transferred to the classroom. Based on these results, the following three concepts can help illustrate how gameful design can help cultivate mêtic intelligence in the composition classroom:

- Mêtic strategies begin as both deliberate and unintentional responses, with ample opportunities for repetitive practice in order to help them become more embodied over time.

- Mêtic strategies must be rewarded, and though non-mêtic strategies are permitted, they often have higher risk and are clearly established as less efficient.

- Mêtic strategies often rely on deliberate modal cueing (visual, auditory, textual, etc.) that may at first be difficult to notice, but through repetition become internalized.

With these concepts in mind, we can begin designing our courses in ways which help cultivate mêtic intelligence. To begin, from the very first day in class, we must establish and provide opportunities to practice mêtic strategies so they may become habitual over time. For example, a given course could have the same genre of opening activity at the beginning of each class, where students are able to move through the activity more quickly as they become more practiced and receive feedback. This could be something as simple as pulling a quote from the reading each day and spending the first five to ten minutes unpacking a quote each class or starting each class with students briefly discussing the reading with a partner before opening to a larger class discussion.

When cultivating mêtic responses, the key thing is to enact the practice at the start of every class in order to build it as a habit; eventually students may even come to class and start discussing in pairs without prompting since they know it happens every class meeting. In addition, as a key feature in open world games is their ability to provide instant feedback, these activities should allow students to see their progress as near immediately as possible; online learning systems such as Moodle and Blackboard are most likely the best option due to the need for immediacy, but analog means of tracking students’ progress, so long as they can be easily and frequently accessed, may also work. Moving from a pair discussion to a larger discussion where students feel more confident in their responses would also be an example of this near-immediate feedback loop, though it would certainly require a few repetitions to establish itself. That said, as noted by Gee and others, reproducing the immediacy of feedback from video games in the classroom can be difficult: more research is necessary to further develop and test such strategies and their potential benefits here.

Moving from feedback itself, rewarding mêtic strategies in a classroom setting may appear difficult due to the previously discussed difficulty of observing mêtis in action. In addition, our desire as instructors to provide clear, explicit instruction to our students means that we sometimes deny them the possibility of utilizing more mêtic responses in favor of a more straightforward approach. As such, prioritizing and rewarding student choice becomes a key element in classrooms seeking to encourage students’ mêtic intelligence. Assignment design, then, provides the opportunity to allow students to choose for themselves which strategies will work best for a given writing task. In addition, students should be able to use more conventional approaches, such as using Powerpoint if they are to give a presentation, but such approaches should be designed to be less efficient or facilitate more risk than others. For this particular example, this could mean having additional requirements for students opting to use Powerpoint in order to encourage them to take a different route or use a less familiar platform. However, despite the increased difficulty and/or time investment when taking the more familiar or straightforward approach, any detriment incurred by trying this method cannot be permanent. Rather, assignments should be designed to give students not only a chance to revise their initial strategies, but perhaps even change to a completely different one, without permanently affecting their grade. Working with point increment systems or grading contracts can also help with this particular strategy, as they allow students to take more risks while still providing some form of a safety net, creating safe spaces for failure in the classroom by allowing students to experiment with different strategies, fail, and perhaps try again, without detriment to their grade. This overlap with existing scholarship on pedagogies of failure (see Micciche and Carr’s Failure Pedagogies) is yet another place where additional research would further develop actionable steps for bringing and cultivating mêtis in the classroom, but such work goes beyond the scope of the current project.

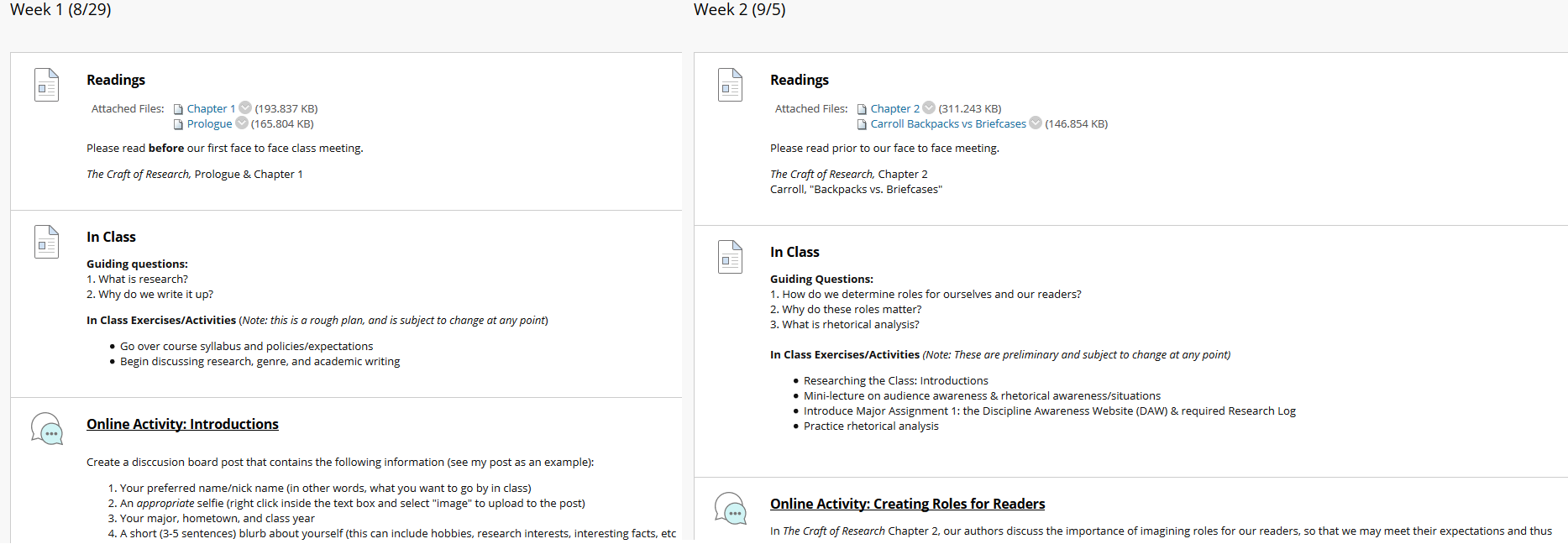

Finally, this case study suggests that emergent gameplay in open world games becomes tacit through the repetition of modal cues, be they visual, auditory, linguistic, spatial, or gestural. These cues are established from the very beginning of the game, with obstacles and puzzles becoming increasingly complicated, but still relying on the same initial cues as the player progresses. For our classrooms, then, this reinforces the importance of consistent document design, and may even suggest moving to more digital-based (or at least digitally designed) assignment sheets to help maintain such consistency. It also suggests that as instructors we may want to develop and utilize specific phrases or gestures associated with particular activities or discussion prompts to indicate that we want particular kinds of responses and/or to prime students to think in particular ways. If an instructor waves their hand in the same motion every time they ask if anyone has any questions, for example, they could eventually rely only on the gestural cue to prompt questions. However, as the key here is repetition, the first step to incorporating such design into the classroom means paying attention to how information is laid out for students, and ensuring the same information is laid out in the same way throughout the entirety of the course, regardless of the mode the cue takes. This can often most easily be seen in the online platforms that often accompany our classrooms. Blackboard, for example, uses particular symbols as a visual cue for each type of assignment. Using these images, we can create repetitive visual cues for our students so they know what’s expected of them just from a quick glance.

Figure 2. Using Repeated Visual Cues on Blackboard

Rather than merely having a folder labeled “Readings” or something similar, breaking down a course into particular weeks and developing a pattern that each week follows can help students internalize the mêtic strategies they develop to succeed in the course. The figure above provides an example of such repetition and visual cues. Online assignment sheets made through Prezi, Piktochart, or other online platforms that rely more on visuals can also encourage habit-forming strategies by providing clearer cues and explicitly linking these visuals with a particular goal or assignment criteria, but instructors could also develop particular cues in any or even across multiple modes to help further ingrain such habitual responses and encourage students to practice the mêtic strategies they’ve gained throughout the course. In short, the use of repetitive cueing helps students make connections between assignments and activities, as well as helps them develop their own mêtic habits and strategies for completing the course.

Conclusion: Cultivating Cunning in the Composition Classroom

In her article Interrupting Gender as Usual: Metis Goes to Work, Ann Brady makes the case for the need to bring mêtis into Women’s Studies pedagogies, arguing that “problem solving is thus often introduced to students as a checklist, or tool . . . however, rhetorical problem solving can play a much broader role . . . insofar as it encourages writers to think about their purpose as it intersects with the needs and attitudes of their audiences” (217). She then offers mêtis as a way to avoid the positioning of problem solving as a “checklist” for students to follow, as mêtis allows students to make “decisions that are not so much efficient as they are sensitive to shifting contexts” (217). Following this line of thought, the construction of a pedagogy that combines both mêtic intelligence and the concept of possibility space creates a classroom space that not only relies on mêtis as a central concept, but also cultivates mêtic strategies within both students and instructors.

Because this approach refuses to posit problem solving as a “checklist,” and instead illustrates the need to examine and illuminate implicit procedures and expectations, it provides an essential tool for students to understand the kinds of flexibility needed in writing courses especially, where students learn to navigate these shifting contexts. In addition, designing a course so that it not only allows for, but encourages and provokes mêtic strategies helps students develop their own sense of rhetorical agency and moral responsibility. Within the composition classroom, the adoption of mêtic practices often comes naturally, especially because mêtis is so often tacit or implicit in our phronetic experiences. As a field, then, we are already focused on making the often-implicit expectations of writing explicit for our students. mêtis lets us take this a step further by giving our students a tool they might then use to upend or otherwise subvert those expectations, especially in instances when the expectations do not account for their lived experiences. In short, by cultivating cunning, we grant our students the power to “see the world slightly differently” (Dolmage 9), and to use that power to become agents of cultural change.

Notes

[1] The virtuous Odysseus was once considered the embodiment of mêtis, as the original Greek term pointed to a quality that combined both wisdom and cunning, especially when such qualities led to change in the larger world.

[2] Gee points to this as well in his discussions of the differences between learning and acquisition in Learning, Discourse, and Linguistics and the idea of writing as craft/techne in Atwill’s “Techne and the Transformation of Limits.”

[3] Retreating from enemies in BOTW is far more difficult when fighting with close range weapons, especially in the case of multiple enemies, as while you focus on one, the others will flank you.

Works Cited

Alexander, P. KNOWing How to Play: Gamer Knowledges and Knowledge Acquisition. Computers and Composition, vol. 44, 2017, pp. 1–12.

Ash, James. Technologies of Captivation: Videogames and the Attunement of Affect. Body & Society, vol. 19 no. 1, 2013, pp. 27–51.

Atwill, Janet. Rhetoric Reclaimed: Aristotle and the Liberal Arts Tradition. Ithaca, NY: Cornell UP, 1998.

Bogost, Ian. The Rhetoric of Video Games. The Ecology of Games: Connecting Youth, Games, and Learning, edited by Katie Salen, The John D. and Catherine T. MacArthur Foundation Series on Digital Media and Learning, MIT P, 2008, pp. 117–140, doi:10.1162/dmal.9780262693646.117.

Brady, Ann. Interrupting Gender as Usual: Metis Goes to Work. Women’s Studies, vol. 32, 2003, pp. 211–233.

Caravella, Elizabeth. Procedural Ethics and a Night in the Woods. The Ethics of Playing, Researching, and Teaching Games in the Writing Classroom, edited by Richard Colby, Mathew S.S. Johnson, and Rebekah Shultz Colby, Palgrave MacMillan, 2021, pp. 97–113.

Detienne, Marcel, and Jean-Pierre Vernant. Cunning Intelligence in Greek Culture and Society. Trans. Janue Lloyd, U of Chicago P, 1978.

Dolmage, Jay. Metis, Mêtis, Mestiza, Medusa: Rhetorical Bodies across Rhetorical Traditions. Rhetoric Review, vol. 28, no. 1, 2009, pp. 1–28, doi:10.1080/07350190802540690.

Dudeney, Gavin, Nicky Hockly, and Mark Pegrum. Digital Literacies. Routledge, 2014.

Gee, James Paul. Good Video Games and Good Learning: Collected Essays on Video Games. Peter Lang, 2008.

Hawhee, Debra. Bodily Arts: Rhetoric and Athletics in Ancient Greece. U of Texas P, 2004.

Holmes, Steven. The Rhetoric of Videogames as Embodied Practice: Procedural Habits. Routledge, 2017.

Kopelson, Karen. Rhetoric on the Edge of Cunning: Or, The Performance of Neutrality (Re)Considered As a Composition Pedagogy for Student Resistance. College Composition and Communication, vol. 55, no. 1, 2003, pp. 115–46.

McAlear, Rob and Mark Pedretti. Writing Toward the End: Students’ Perceptions of Doneness in the Composition Classroom. Composition Studies, vol. 44, no. 2, 2016, pp. 72–93.

McGonigal, Jane. I’m Not Playful, I’m Gameful. The Gameful World, edited by S. Walz and S. Deterding, MIT Press, 2014, pp. 653-658.

McDermott, Lydia. Birthing Rhetorical Monsters: How Mary Shelley Infuses Metis with the Maternal in Her 1831 Introduction to Frankenstein. Rhetoric Review, vol. 34, no. 1, 2015, pp. 1-18.

Micciche, Laura and Allison Carr. Failure Pedagogies: Learning and Unlearning What it Means to Fail. Peter Lang, 2020.

Nintendo. The Legend of Zelda: Breath of the Wild. Nintendo EPD, 2017.

Pope-Ruark, Rebecca. A Case for Metic Intelligence in Technical and Professional Communication Programs. Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 23, 2014, pp. 323-340.

Shultz Colby, Rebekah. Game-based Pedagogy in the Writing Classroom. Computers and Composition, vol. 43, 2017, pp. 55-72.

Weidner, Matthew. Nintendo Wire’s Switch Game of the Year 2017 Award. Nintendo Wire, Dec. 30th 2017, https://nintendowire.com/news/2017/12/30/nintendo-wires-switch-game-year -2017-award/.

Playing with Mêtis from Composition Forum 52 (Fall 2023)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/52/playing-with-metis.php

© Copyright 2023 Elizabeth Caravella.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 52 table of contents.