Composition Forum 25, Spring 2012

http://compositionforum.com/issue/25/

The Peer-Interactive Writing Center at the University of New Mexico

Abstract: The one-on-one format of tutoring, which is the norm for writing centers, can foster the much-maligned view of a writing center as a fix-it shop and undermine the role of the tutor as a co-learner and facilitator of peer-to-peer interactions. The peer-interactive writing center approach, presented here, moves away from the one-on-one model and towards a format that encourages genuine peer collaboration, recreates the writing center as a place to actually engage in writing, and encourages students in their intuitions about writing. As a case study of such a peer-interactive approach, this profile provides an overview and evaluation of the Writing Drop-In Lab at the University of New Mexico, which provides a model for bringing the practice of writing tutoring into line with a view of writing as a collaborative, process-oriented phenomenon.

Heading into the second decade of the 21st century, the typical university writing center stands firmly on two theoretical feet: Expressivism, with its focus on the writer’s experience of self-discovery, exploring, and learning in the creation of a text (and the resulting authenticity and writer ownership of the resulting text), and Social Interactionism, which emphasizes writing as a social act most fruitfully approached as a collaborative exercise. The former advocates the engagement of writing tutors with students’ processes for writing and stresses invention and drafting in tutoring sessions (see Peter Elbow, Ken Macrorie, Donald Murray, and Stephen North). The latter, in the context of the writing center, focuses on the role and relationship of the tutor and tutee, advancing a view of the ideal writing tutor as a peer consultant who downplays their own authority in order to act as a co-learner in the enterprise of writing (see Andrea Lunsford). The two approaches work in concert to develop students’ sense of authority as writers. Students navigate a process for bringing their own ideas to fruition that includes both individual exploration (as in student-led sessions in which tutors make liberal use of the Socratic method to draw out student writers’ intuitions about writing) and participation in a dialogue that brings ideas into beneficial conversation (as in peer-review sessions facilitated by writing tutors).

These ideas are no longer merely formative. While writing program administrators certainly still work every day to combat older notions (grounded in traditional rhetoric and a view of writing programs as remedial) of what a writing center is, what it does, and who it serves, these are the accepted pillars of current best practice, also serving as the axioms upon which newer, Writing Across the Curriculum (WAC)-oriented approaches to writing center theory are based. Every semester, hundreds of new writing tutors across North America and around the globe read Stephen North’s “The Idea of a Writing Center” and march off to their first sessions with students under the aegis of “Better Writers, not Better Writing!” Tutors are prepared in meetings and training programs to engage with student texts as outputs of the process whereby they are created rather than as ends in and of themselves, and to provide direction that will help students to grow and develop as writers rather than merely to turn in a more polished piece of writing in the immediate future. While these ideas continue to evolve and to be challenged and expanded upon in the literature, a clear state of the field incorporating the above ideas has arrived, accompanied, within our field, by a broad consensus as to our shared values and goals.

There is one place, however, where outdated views of the writing center persist, and it’s not a discipline, academic department, or institution. It’s the mainstay of the writing center, the core of our practice, and the main way in which writing tutors engage with student writers: the individual consultation. With respect to both engaging with students’ writing processes and to fostering a view of writing as a social act, individual consultations can fall short of (and, in fact, undermine) our goals.

There’s an enormous amount of variation in how individual consultations are practiced in different centers, but there are two defining aspects. First, students work one-on-one with writing consultants; sessions may, on occasion, involve more than one student, but this is the exception rather than the rule, and the models for tutoring applied by consultants assume a single student writer. Second, individual consultations have time constraints, either explicitly (being scheduled in set blocks of time) or implicitly (as in a walk-in center where tutors are working with students on a first-come-first-served basis). The first means that in a typical visit students aren’t exposed to other students’ writing and that they receive feedback only from a single person. The second encourages students to do their writing outside of the center and to use the limited time of an individual appointment to receive feedback focused on a draft. Wonderful things can and do happen within individual consultations, and there will always be a place for individualized sessions in a center that aptly serves all comers. However, the format, by its nature, encourages draft-centered sessions focused on tutor feedback and discourages engagement earlier in the writing process and across peers.

In an attempt to move away from one-on-one, tutor-tutee sessions that occur within set time limits, we at the University of New Mexico implemented a new format for tutoring, the peer-interactive writing center approach, in order to promote informal peer-review sessions, scaffolded group work, and the direct support of students in the process of writing itself. The methods of the peer-interactive writing center approach, as exemplified in what we’ve implemented and marketed at the University of New Mexico as the Writing Drop-in Lab, skew things in the other direction: towards peer feedback and engagement with the writing process itself, and away from sessions focused on tutor feedback. Within the Writing Center at the University of New Mexico, the Writing Drop-In Lab is an experiment with creating a model for peer tutoring which places the goals and methods of the peer-interactive writing center approach at the center of practice. The approach is built on methods already applied in excellent academic writing centers that set aside an important place for student peer reviews{1} as well as for group sessions{2} and is also informed by the methods used in many non-academic writing centers that cater to the needs of the writing community at large (foremost among these methods being workshops in which participants share and critique one another’s writing){3}. It is kindred in spirit to the movement towards classroom-based writing tutoring (CBT), which advocates for the development of programs that place peer tutors into classrooms where they can engage with a wider cross section of the student population and support and educate faculty on the effective integration of writing into a course (see Margot Iris Soven as well as Candace Spigelman & Laurie Grobman) in that it challenges long-standing assumptions about the nature of a writing center, and in particular the role of a peer tutor. Whereas CBT, however, focuses on what takes place outside of the walls of the writing center, the peer-interactive writing center approach provides a model primarily for what happens within it. Our name for our version of this approach, the Writing Drop-In Lab, enthusiastically adopts the “lab” designation, adopting a metaphor whereby a writing center is understood not merely as a place to discuss and learn about writing, but to actively engage in it. In what follows, I will describe the Writing Drop-in Lab, report on findings from its assessment, and look ahead to its future.

Overview of the Writing Drop-in Lab

Within typical writing center appointments, students work individually on their writing elsewhere (in computer pods, in their dorm rooms, at their parents’ homes, in coffee shops, and many other locations), get feedback and guidance from a tutor in the writing center, and then leave the center again to incorporate the feedback. The focus in the UNM Drop-In Lab, on the other hand, is for students to write, either on their own or in groups, in the lab itself, with tutors close by to offer assistance as it is needed.

As I describe in greater detail below, the Writing Drop-in Lab is located within the UNM Writing Center, which is itself part of the Center for Academic Program Support. Students make no appointments for visits to the Drop-in Lab; students are welcome to come at any point during its hours of operation (these currently totaling 49 hours/week) and stay for as long as they like (sometimes for five minutes to ask a brief question, often for hours at a time to complete a substantial amount of writing). The space is a mix of tables and workstations with a laptop set up at them; a student receptionist logs in students as they enter the space. The Drop-in Lab is staffed at all times by between 1 and 3 (depending on the typically attested utilization of the lab at any given time) peer tutors who circulate among the anywhere from 1 to 20 students in the space, offering input and guidance as it is requested by students. Tutors are trained to frame their input as brief statements of useful principles, based on a review of the student’s writing, and then to leave the student to work on integrating the feedback while the tutor attends to other students. Thus, for example, a tutor might respond to a student’s raised hand by reviewing the introduction that the student has just written in the lab, briefly talking about general guidelines for introductions and statements of thesis, and then moving on to begin a conversation with another student while the first student writer works to apply the tutor’s feedback.

Tutors are also trained to provide scaffolding guidance for students who are writing in groups, and to facilitate peer review among student writers. Most tutors working in the center are undergraduates, in the interest of preserving a peer dynamic. One notable exception to this is the graduate students who act as Student Managers, greeting students as they come in and orienting them to the space, inviting them to get to work writing, and advising them that tutors are available as needed. The other major role of these Student Managers is to seat students from the same course or from similar courses together at tables and adjacent workstations. Peer review arises gratifyingly often on an informal basis in this environment, with minimal prompting from Student Managers and tutors. A formal peer review guide is also available for students (see Appendix 1).

Within this environment, then, two activities are explicitly fostered: writing, and talking about writing. Writing forms the greater part of activity in the center; conversations about writing take place both as student-tutor interactions, and as student-student interactions (the latter albeit with frequent scaffolding from tutors).

Goals of the Writing Drop-in Lab

The Writing Drop-In Lab was established with the following five goals:

1. To implement in practice a view of writing as a process

Teaching writing as a process rather than as a final product has long been a goal of writing centers, as well as composition and WAC programs. Despite a long-standing policy of advertising the writing center as being available for students at any stage of the writing process, both students and tutors tend to think of a completed draft as prerequisite to a productive tutoring session. The vast majority of individual appointments take place around such a draft, and students often feel that they can’t make an appointment until they have a draft completed. The reasons for this are understandable; with a set amount of time during which to conference with a tutor, the choice to complete a draft beforehand so that the session itself can focus on feedback is a shrewd one. The outcome of this, however, can be unfortunate. Sessions focused on completed drafts reinforce an idea that the writing process is important only insofar as it contributes to the final form that the finished product takes. Sessions that take place during the process leading up to a completed draft reinforce another idea: that development as a writer is in large part a matter of developing one’s process of writing. Within the Writing Drop-in Lab, students with no constraints on the amount of time that they can spend in the center use the Lab to engage in the actual creation of texts. Rather than being placed into the role of commenting on a completed (for example) statement of thesis or concluding paragraph, diagnosing issues in the drafting process and making suggestions to be implemented in revision, tutors are able to engage students before or while they write, reminding students of key aspects of a statement of thesis or guiding students through rereading the body of a paper as a wind-up to writing a concluding paragraph.

Knowledge of the process of planning, crafting, and revising written communication is an essential aspect of development for college writers. Tutors engaged with a completed draft see only an outcome of this process. In working with student writers who are actively writing and pre-writing, tutors can engage with the writing process itself, diagnosing issues related to how students approach writing. Additionally, students who have completed a draft tend to want sessions focused on surface issues (grammar, spelling, etc.), a preference often shared by tutors who find such issues easier to diagnose than concerns relating to style, organization, and audience. Sessions that take place earlier in the writing process allow tutors to provide input on these deeper issues.

2. To embody a view of writing as a collaborative act

A core guiding principle of the “new” writing center, as informed, in particular, by social interactionism, is that writing is most effective when it is surrounded by conversation and discussion. Facilitating peer interactions among student users creates a dialogue around writing that helps to lead student writers away from a view of writing as a solitary activity and towards a view of writing as a social activity.

In traditional individual appointments, the focus is on one-on-one interactions. Group sessions occur, but they are the exception rather than the rule. In the Drop-In Lab, by contrast, students often casually consult one another on their writing. Tutors facilitate peer review sessions for groups of students working on the same assignment, and students working on group projects meet in the presence of a tutor who can help to facilitate genuine collaboration.

One of the most common laments of writing center directors—the rush of students who come into the writing center in the last few days before an assignment is due—becomes an asset, as students from the same or related courses are seated in groups to discuss the assignment, review one another’s work, and create a dialogue around writing.

3. To validate student users as intelligent commenters on ideas and writing

Peer review has the obvious reward of providing feedback for the student writer. The more important benefit is also the more commonly overlooked one: commenting on other students’ work validates student writers as authorities on writing, able to formulate meaningful and helpful responses to not only their peers’, but also their own, writing. In addition, the practice fosters students’ metacognition, which can facilitate the transfer of skills. The approach addresses the tendency of individual appointments to foster inherently unequal power dynamics (see Michael Joyner, Carol Stanger, Susan Strauss and Xuehua Xiang, and Caroline Walker). Ultimately, by shifting the authority away from tutors and toward the student users, the writing center creates more independent writers.

4. To advance a view of the writing center as a place to write, rather than as a place to get writing fixed

The much-decried view of the Writing Center as a fix-it shop is, in some ways, a consequence of a model in which students write, then see a tutor, and then revise based on the session. Advertising the Writing Center as a place for students to work on their writing fosters a healthier image of the center, as a place for the student to learn and engage in good writing practices.

A major approach for tutors in the Drop-In Lab is to work with a student for ten to fifteen minutes, discussing and reading over the assignment and working with the student user to prioritize areas to focus on in the session. The tutor then leaves the student user to work independently for another 15 to 30 minutes (often while the tutor goes to check in with another student) before checking back in to see how feedback has been implemented.

5. To increase student usage by more effectively utilizing tutors’ time

By freeing up tutors to work with multiple students simultaneously and allowing students to drop into the writing center without having previously made an appointment and at whatever time is convenient for them, the approach has the potential to greatly increase tutor utilization in the Writing Center. Writing Center staff members make use of workshopping, peer review, and group learning techniques without creating an undue load on themselves— and in doing so, meet each of the above goals more effectively than they can within individual appointments.

Implementing the Writing Drop-In Lab at the University of New Mexico

The University of New Mexico is a large, public, research university serving a highly multicultural and multilingual student population. The Writing Center, of which the Writing Drop-in Lab is a part, has existed since 1981, as part of a larger learning center. It is a large writing center, currently seeing 2,000+ visits/semester. The Writing Drop-In Lab was instituted with the above-mentioned goals in Fall of 2009. The sections that follow provide a brief overview and timeline of the Lab’s development. Table 1 presents total student visits to the main location of the UNM Writing Center, from Fall 2008 to Fall 2010.

| Semester | Individual Appointments | Writing Drop-In Lab |

|---|---|---|

| Fall 2008 | 1643 | NA |

| Spring 2009 | 1321 | NA |

| Fall 2009 | 858 | 536 |

| Spring 2010 | 525 | 582 |

| Fall 2010 | 628 | 1416 |

Table 1. Visits to the Writing Center, Fall 2008 to Fall 2010

Fall 2008, Spring 2009

In all semesters prior to the Fall of 2009, writing tutoring was available in two formats, both standard for writing centers nationally: individual consultations, and walk-in tutoring. In individual consultations, students come to or call the front desk, where they are scheduled for an appointment lasting for 25 or 50 minutes with a writing tutor. During walk-in times, students do not need an appointment to see a tutor. Tutoring is individual, such that at busy times students wait to work with the tutor in the order they arrive. Both formats, as practiced in our center, were and are guided by current best practices: tutors engage the students in a dialogue around writing, working together to negotiate the session.

The Writing Center at UNM is, as mentioned above, situated within a larger learning center (the Center for Academic Program Support, or CAPS). While at many institutions the struggle to separate writing tutoring from content tutoring has been a positive one, signaling a program coming into its own, the emergence of the peer-interactive writing center approach points to the possibilities for cross-pollination of ideas that can emerge when tutoring programs share a roof. STEM (Science, Technology, Engineering & Mathematics) tutoring at CAPS takes place largely on a drop-in basis, with the student population the program serves being well educated on and well-accustomed to utilization of the tutoring center as a place to come multiple times per week for long stretches of time to do their homework within a scaffolded environment. The exigence for the peer-interactive writing center model was, for the author (at the time, a newly hired professional staff member inheriting a well-regarded program), a combination of the issues noted above with individual sessions, and the propinquitous example of the Math and Science tutoring labs. I developed a proposal for the Writing Drop-in Lab that operated within the existing budget for the Writing Center (which remains true through the present, although that overall budget has grown as a response to the highly increased student visits created by the Drop-in Lab), spent the Spring and Summer of 2009 working with a supportive Director to implement it, and assumed administration of it as a part (and, eventually, the core) of the overall Writing Center in Fall 2009.

The Writing Center has several satellite locations around campus, but its main location (where individual appointments were, and continue to be, held, and the space within which the Writing Drop-in Lab was implemented) is within one of the main University Libraries.

Fall 2009

The Writing Drop-In Lab, with its peer-interactive format, was implemented in the Fall of 2009. The Lab, located within the larger Writing Center, was open during the hours of 12 pm to 4pm Monday through Saturday: hours of peak utilizations for the Writing Center (the full hours of which extended from 9am to 6pm). During these hours, individual appointments were no longer available for writing, and receptionists at the center were instructed to refer students seeking appointments during these times to the Drop-In Lab.

Six laptops were purchased, placed out during drop-in hours as workstations for students (along with two desktops, providing 8 total workstations). In advertising, students were encouraged to bring their own laptops or to work on one of the Writing Center’s computers. In all campus outreach (class visits, e-mails to the faculty listserv, and printed Writing Center materials), the Writing Drop-In Lab was advertised as a place for students to engage in writing, either alone or in groups, and with or without the assistance of writing center staff. The Appendix 2 contains the current (as of November 2011) Writing Center hours flier, our primary printed outreach tool, which very briefly introduces students to some of these core aspects of the drop-in format.

The major challenge of the first semester was training the writing center staff on the new format of tutoring, which included persuading them of its merits so that their motivation to use the tools it offers was internal rather than enforced from above. Training for Fall 2009 began with an introduction to the new format of tutoring. In training the tutors, I focused on the theory behind the approach, and on strategies for the tutors to use in engaging with writing earlier in the writing process (e.g., drawing out critical information from a prompt, reading sources critically, and pre-writing activities such as freewriting and clustering) and diagnosing issues in the writing process (e.g., beginning to write without a plan of action, a linear approach that impedes students who feel that they must write an introduction before they can proceed to body paragraphs, or a crippling focus on surface issues in the early drafting stages). As a rule, new tutors took to the new format readily, while returning tutors (in particular those who had spent more than a few semesters tutoring in the center) were acculturated to intensive one-on-one interactions with students and had a difficult time making the switch to the new format. In many cases, tutors who were enthusiastic about the new approach still had a difficult time not treating the new format as simply first-come, first-served sequential one-on-one sessions.

A veteran graduate student writing tutor was given a position as the Student Manager for the Writing-Drop in lab, supervised by me. This manager’s duties include overseeing the flow of student usage in the Drop-In Lab, assisting with training the tutors on the new format of tutoring, orienting new student users to the new format of tutoring, and providing oversight for the lab.

In terms of usage, as indicated in Table 1, the overall number of visits at the Writing Center remained steady from previous semesters, as the number of drop-in visits greatly increased and the number of individual visits decreased correspondingly.

Spring 2010

Heading into the second semester of the Writing Drop-In Lab, the writing center staff was composed entirely of tutors who had either spent at least one semester being exposed to the drop-in format, or who were new to the center and therefore saw nothing unusual in the Drop-In Lab format. Time, training, and turnover had effectively dealt with the issue of tutor resistance to moving from the familiarity of one-on-one tutoring to the new system, and the emerging issue became educating student users on the new format of tutoring. The focus of Spring 2010 was to counter students’ expectations that a visit to the writing center meant one-on-one time focused around a draft and also to address reticence around sharing writing. The tutors, the student manager mentioned above, and I invested time in educating new and returning student users on the Writing Drop-In Lab: what it is, and how to use it. In class visits, tutors explained the concept of the peer-interactive approach to students, explaining that they can use the Writing Center as their primary place to write, and that tutors can help students to work productively in groups. They also worked to set up the expectation that students will share their writing with other students. Additionally, in-class and out-of-class workshops focused on leading students in peer review, so as to expose students to and model the pedagogy of the center. In the Drop-in Lab itself, the tutors and Student Manager worked to counter expectations among student users that a draft was prerequisite to visiting the center, and that students needed to leave the center in order to incorporate revisions. In all promotions, a central message is that writing at home alone leaves an author with little recourse when they are uncertain of how to proceed, whereas in the Center there are always other students and tutors from whom to seek guidance in moving forward.

In the Fall of 2009, all writing tutors were expected to spend some time engaged in drop-in tutoring. In the Spring, more attention was paid to tutors’ relative aptitudes for drop-in vs. individual tutoring. In some cases, tutors’ reticence to circulate among students was a matter to be amended with training; in others it was a better solution to allow tutors for whom one-on-one interactions was a strength to remain focused on individual sessions. Tutors demonstrating a knack for collaborative learning strategies and building a group dynamic had their time prioritized for the Drop-In Lab. However, a major concern voiced by tutors, addressed in training for subsequent semesters, was a need for tools and strategies for engaging students in interactions with one another.

Fall 2010

A central goal for the first year had been to acculturate students to the new format of tutoring, encouraging them to take advantage of it by making it the only format of tutoring available during peak hours. For the Fall of 2010, the hours at the Drop-In Lab were expanded considerably, to encompass the full hours of operation of the center: 9am to 7pm Monday through Friday, and 12pm to 4pm on Saturday. Whereas in previous semesters the Writing Drop-In Lab and individual appointments were offered on a complementary schedule, for the Fall of 2010 both services were offered concurrently throughout the day (such that students could choose between the two services for any given time, and allowing for a preference for one-on-one sessions among individual student users).

Visits increased dramatically. Visits to the Drop-In Lab nearly tripled from Fall 2009. Interestingly, this happened without a sharp decrease, over the same period, in visits to individual appointments. Fall 2010 was, by a handy margin, the Writing Center’s busiest semester to date.

Fall 2010 saw three new locations for the Drop-In Lab’s peer-interactive format hosted by other campus organizations (a student ethnic center, the university advisement center, and a computer pod in the student union building). These locations were opened with the rationale that writing tutors could most effectively engage with the writing process if they go to where students write, rather than wait for the student to come to them. Tutors in these locations circulate through the space, making themselves available to student writers who, having come to use the computers rather than to engage with a tutor or their peers, may or may not avail themselves of the tutors’ services. This program continues to be a success, effectively reaching out to new students and new student populations who may not otherwise have made use of the main location of the writing center. An emerging lesson, however, is that the writing drop-in format (as follows from the interactive model on which it’s based) works well only above a certain critical mass, in terms of the volume of student users making use of the space. At slower locations it is less suited.

Fall 2010 was an exciting semester for seeing the fruits of previous semesters’ efforts. The major focus in training sessions was developing tools for facilitating groups: peer review, scaffolding group collaboration, and workshopping model texts. Whereas in previous semesters much of the tutoring in the Drop-In Lab remained interactions between one tutor and one student user, it’s now increasingly common to see students working in groups— indeed, students now sometimes arrive at the Center in groups, something almost unheard of as recently as 2008. Many more students come to the writing center to write, in some cases staying for hours and only occasionally asking for assistance from a tutor.

While signs such as this seemed to indicate that the Writing Drop-in Lab was successfully changing how students used the Writing Center, a programmatic assessment was clearly called for in order to establish whether the program was meeting the goals that it had been designed to meet. This assessment was created and implemented in the Fall of 2010.

Assessment of the Writing Drop-In Lab

The Drop-In Lab’s five goals presented above were assessed using a survey distributed to the writing center staff, a survey distributed to student users of the Writing Drop-In Lab, and a survey of usage data.

Writing Center Staff Survey

The tutor survey, administered using http://www.surveymonkey.com, was distributed electronically at a Writing Center staff meeting on October 8, 2010. In the survey instrument, tutors were first provided with a description of each of the first four objectives. An initial set of questions directly assesses how the tutors rate the effectiveness of the Drop-In Lab vs. the effectiveness of individual appointments at meeting the goal in question, on a scale of 1 to 5, with an increase in numerical quantity corresponding to an increase in perceived effectiveness. A second set of questions asks tutors how often, on a text scale ranging from “all the time” to “never,” they utilize particular collaborative strategies on which they have been trained. Tutors were seated at computers and directed to the survey instrument. They were provided brief instructions on the survey, and advised that all responses were confidential. A total of 17 tutors completed the survey.

Table 2 presents the results of the first set of questions.

| On a scale of 1 to 5, with 1 corresponding to "not at all effective" and 5 corresponding to "very effective," how would you rate each format of tutoring at meeting: | Individual Appointments | Writing Drop-In Lab |

|---|---|---|

| Objective 1: implementing in practice a view of writing as a process? | 3.33 | 4.47 |

| Objective 2: embodying a view of writing as a collaborative act? | 2.83 | 4 |

| Objective 3: validating student users as intelligent commenters on ideas and writing? | 3.09 | 3.64 |

| Objective 4: advancing a view of the writing center as a place to write, rather than as a place to get writing fixed? | 2.17 | 4.27 |

Table 2. Mean effectiveness for individual appointments vs. Drop-In Lab, averaging across participants (n=17)

For each of the objectives 1 through 4, the average rating is higher for the Writing Drop-In Lab than for individual appointments, indicating the writing center staff as a whole perceives the former to be more effective in satisfying the stated objectives.{4} The results of these questions clearly indicate that, from the perspective of the tutoring staff, the Writing Drop-In Lab is meeting its stated goals more effectively than individual appointments.

Objective 2, as well as the training needs of the staff, was addressed with an additional set of questions relating to tutors’ use of collaborative strategies. Table 3 presents the results of this set of questions:

| In the Writing Drop-In Lab, how often do you… | All the time. | Sometime. | Not very often. | Never. |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Work in a group with two or more students who have similar issues/papers? | 6.3% | 37.5% | 37.5% | 25% |

| Arrange students into peer-review groups, with students working on the same or similar assignments reviewing and commenting on one another’s work? | 0% | 12.5% | 43.8% | 43.8% |

| Run a short, informal workshop on a topic that multiple students in the lab are facing? | 0% | 12.5% | 31.3% | 56.3% |

Table 3. Estimated frequency (percentage) of tutors using key strategies

Here we see a tutoring staff in transition, with most tutors making at least some use of specific strategies on which they have been trained, and others not. Tutors’ comments explaining their answers for this set of questions indicate that, as of the beginning of October 2010 (mid-semester), the lab simply hadn’t yet been busy enough to provide an opportunity for these strategies. Nonetheless, these results point to a need for further training, particularly on peer review.

The responses to these questions offer evidence that Objective 2 is, to some extent, being met, with a number of tutors making use of collaborative strategies (peer review, mini-workshops, collaborative writing) in the Drop-In Lab. They also, however, point to a clear issue for future training: a gap between the pervasiveness of collaborative techniques in the Drop-in Lab as envisioned by its administrator and perceived by tutors (despite, as is indicated in table 2, the fact that tutors do recognize the collaborative value of the Drop-in Lab), and the Writing Drop-in Lab as implemented in practice.

Student User Survey

The student user survey was administered to all students who visited the Writing Center (both in individual appointments and the Drop-in Lab) during a two-week long period in the Fall of 2010. All 292 students who used writing tutoring during this period received an email, following their first visit during the target period, with a link to the survey instrument. The survey was administered electronically through Student Voice, an online survey design and administration tool that provides an html link, included in the email, for participation. Students were advised that all responses were confidential, and no identifying information was collected in the survey. A total of 56 student users completed the survey. Of these, 53 were users of the Drop-In Lab, and it is results from these 53 students which are analyzed below.

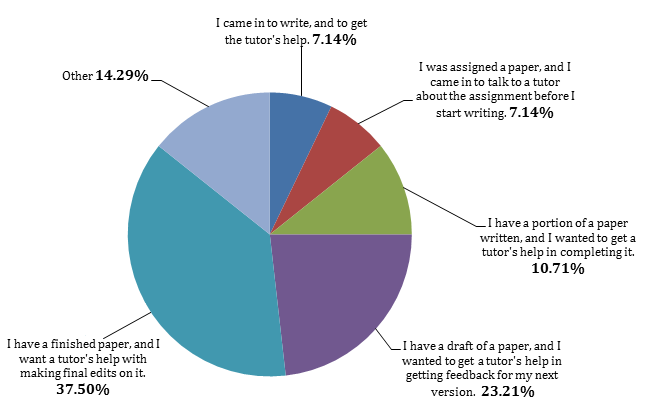

The survey opens with a question on the reason why the student visited the writing center:

Figure 1. Question 1: Student user visits to the writing center, by reason. 37.5% want help editing a finished paper; 23.2% want feedback on a draft; 10.7% want help finishing a paper; 7.1% want help before beginning a paper; 7.1% want help as they write; 14.3% have other reasons.

The responses to figure 1 indicate students’ changing perceptions of the writing center. Fully 39.3% of respondents arrived at the center prior to having completed an initial draft (this tally includes responses from the ‘Other’ category, none of which involve a completed draft), indicating that the Writing Drop-In Lab is clearly meeting its goal of having tutors engage with students earlier in the writing process (supported as well by the 23.21% of respondents who visited the center to seek a tutor’s help in revising towards a subsequent draft). In addition, 7.14% of student users arrived at the writing center planning to write during their time there, speaking directly to the goal of advancing the writing center as a place for writing.

The remainder of the survey poses attitudinal questions directly related to each of the program goals; these data are presented in Table 4.

| After my session today in the Writing Center … | True | False |

|---|---|---|

| 2. I think differently about the process of writing a paper. | 70.00% | 30.00% |

| 3. I'll consider modifying my writing process as I write my next paper. | 73.00% | 27.00% |

| 4. I could see the benefit of coming in earlier in the writing process the next time I use the Writing Center. | 73.00% | 27.00% |

| 5. I think of writing as something that needs to be talked about with other people in order to be done well. | 86.00% | 14.00% |

| 6. I think that feedback from other students is useful in revising my own writing. | 93.00% | 7.00% |

| 7. I think that looking at other students' writing is useful in making my own writing better. | 82.00% | 18.00% |

| 8. I feel more confident in my ability to look at, comment on, and evaluate other people's writing. | 68.00% | 32.00% |

| 9. I feel more confident in my ability to look at, comment on, and evaluate my own writing. | 82.00% | 18.00% |

| 10. I have developed more of an ability to talk about writing. | 70.00% | 30.00% |

| 11. I think of the Writing Center as a place to engage in, and not just talk about, writing. | 73.00% | 27.00% |

| 12. I appreciate the benefit of doing my writing in the Writing Center, as opposed to at home in a computer pod. | 68.00% | 32.00% |

| 13. I plan to do more actual writing in the Writing Center the next time I'm working on a paper. | 62.50% | 37.50% |

| 14. I felt that the tutor who I worked with valued me and my writing. | 84.00% | 16.00% |

| 15. I feel satisfied with my visit to the Writing Center. | 82.00% | 18.00% |

| 16. I plan to use the Writing Center again. | 89.00% | 11.00% |

Table 4. Percentage of students responding ‘true’ or ‘false’ to each attitudinal question

Each set of three true or false questions relates to a particular goal. Questions 2 to 4 focus on students’ perceptions of writing as a process, 5 to 7 on writing as an act requiring social interaction, 8 to 10 on themselves and their peers as intelligent commenters on student writing, and 11 to 13 on the writing center as a place to engage in the act of writing itself. Responses to all of these questions reflect a clear pattern of students’ perceptions of writing being broadly in line with the view of writing advanced by the program, following a visit to the center. The results of the student survey suggest that the Writing Drop-in Lab, at least for those who responded to the survey, is succeeding in its proposed goals.

Questions 14 to 16 are more traditional customer satisfaction questions, included here to assess whether increased tutor utilization (see following section) is resulting in negative perceptions (on the part of student users) of the amount of attention that they are receiving in the writing center. No such relationship is indicated.

Usage Data

Table 5 presents utilization data (student contact hours / tutors’ available hours) for Fall 2008 through the present, for tutors across all tutoring locations.

| Semester | Total Hours available, Individual and Drop-In | % of available hours from Drop-In | Overall Tutor Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Fall 2008 | 2286 | 0% | 63% |

| Spring 2009 | 3573 | 0% | 37% |

| Fall 2009 | 4278 | 61% | 57% |

| Spring 2010 | 2954.5 | 66% | 59% |

| Fall 2010 | 3807 | 70% | 83% |

Table 5. Writing tutor utilization, 2008-2010

The first column shows the sum of tutoring hours available in a given semester, the second the percentage of these hours that come from Drop-In Lab tutoring. The final column shows overall utilization of the Writing Center for the semester in question.

Fall 2010, the semester in which the highest percentage of available hours comes from drop-in tutoring, has by a wide margin the highest rate of tutor utilization, indicating that the goal of increasing tutor utilization is being met. Table 6 shows tutor utilization at the main Writing Center location, contrasting utilization for individual vs. drop-in writing tutoring.

| Tutoring type | Total Hours available | Tutoring contact hours | Tutor Utilization |

|---|---|---|---|

| Individual Appointments | 738.4 | 149.1 | 20% |

| Writing Drop-In Lab | 1217 | 1719.2 | 141% |

Table 6. Writing tutor utilization by tutoring format, Fall 2010

As the 141% utilization suggests, the Writing Drop-In Lab format of tutoring clearly exceeds individual appointments in allowing a tutoring staff to be utilized effectively by maximizing time spent with student users. The results of both surveys demonstrate how, with the appropriate tools and training, this increase in utilization can be accomplished alongside an increase in the overall quality of services being offered.

Conclusion: Reflections from Writing Tutors

No one is better able to address the strengths and pitfalls of the Drop-In Lab’s peer-interactive format than the tutors who work in it every day, informing moment-to-moment decisions on the basis of the goals outlined above. I’ll close with a few reflections from the writing tutors who staff the center (names in quotation marks have been changed at the consultant’s request), before looking ahead to future considerations in the last section. Each of these comments point towards specific ways in which tutors and students have arrived at ways of engaging over writing that are uniquely fostered by a peer-interactive center, emerging from the repositioning of tutors as facilitators of peer-to-peer interactions.

I recently had a student come in with the assignment his teacher had just given him for a paper due at the end of the week. He told me in his own words what the assignment was about, then we read through the prompt together. The teacher had included a rubric, so we then read what an A paper was expected to include. Next, we chose which of the songs and readings from class he wanted to use in his paper. We made up examples, creating a sample outline as we went. Two days later, he came back with a very good paper, which we further revised together. This went well because he came before he had written anything! We were able to get him started on the right track from the beginning.

—Hannah

I had a girl come in one evening having to write a letter to a member of congress concerning a local issue she felt passionately about. She had the assignment and its rubric, but she didn't know where to begin. She told me she had read the assignment but didn't understand what the teacher was asking. So, I read the assignment to myself and, in my own words, explained to her what her instructor was looking for in her paper. We went through the five bullet points point by point, and she wrote down her thoughts in her notebook. After that pre-writing process, I let her work on her own for a bit so she could formulate her ideas more clearly and succinctly. Every once in a while, she asked me to check her work, just to make sure she was on track. She was, and I encouraged her to continue doing exactly what she was. The drop-in format worked so well because, had this been an individual appointment, we would have spent the whole time just on pre-writing—which isn't necessarily a bad thing, but because I knew she wanted to get a good start on it before the day was over, she was allowed the freedom to do that. Another advantage of this format was that I was able to let her write by herself for a little bit, giving her the space and time to think and collect her thoughts without my being over her shoulder.

—Michelle

I was tutoring a student from South Korea; she had a hard time organizing her essay since she felt she could not express herself well in English. I began to talk to her and without focusing on the assignment, after a moment of talking just about her ideas, she was able to elaborate a well- structured essay that covered all points she felt were necessary for the assignment. The interaction was typical for a drop in lab format, since she decided to stay longer and have a conversation instead of just focusing on the assignment.

—‘Chris’

I had one student who had a draft of a paper that she was continuing to work on. It was a longer paper, and when we went through it together, I noticed that it lacked some clarity, and I began to notice that many of her sentences were awkwardly worded. First, we picked one awkward sentence out together and fixed it together. Then we highlighted a couple others together, and I left her to go through the rest of the paper to highlight the rest. When she was done, I looked over them, but then left her to try to fix them on her own. I checked back with her when she was done with that, and she had done a pretty good job fixing them on her own; I might have helped even further clarify some of them, but she had done most of the work by herself. This worked well because she saw her paper as a work in progress. Therefore, I was able to pick out one thing to concentrate on, rather than trying to get everything right. In other words, because she didn't need the paper to be perfect that day, we could start slowly. Also, there was a specific problem that could be fixed in her paper, and that problem had a lot to do with just seeing the issue. Once she started to see what looked awkward, she could easily fix them on her own. This was typical of a good drop in session: being able to step away from the student so that they have to recognize and correct some of their own mistakes makes for the most productive tutoring session. This illustrates the possibilities by showing that students can be active learners in the tutoring process, rather than just passive receivers of corrections.

—‘Sarah’

In each of the above testimonials, tutors speak to how the absence of time constraints allows the session to “breathe,” fostering a productive dialogue around writing. Being able to step away from the session to work with other student users gives student writers time to apply feedback from the tutors. In many cases, the approach encourages students in their own ability to apply principles that they’re picking up from the tutors, including the collaborative discussion of ideas, as indicated by the following tutor’s reflection.

I have had many enjoyable tutoring interactions while working at the Writing Center, but one experience that I found to be especially rewarding involved a freshman student who was working on her first college paper. She was excited about her visit to the center and thrilled about her first semester. She was slightly frustrated with her creative writing assignment. She was asked to write about a memorable experience in her life and had run into a mental block. Before I looked at her paper, I asked her to tell me about her experience. Her words were filled with so much passion and excitement that other students began to listen in. When she was done, several students began to ask her questions. As they conversed, I stepped back and watched as they shared stories and their own ideas of which angle she take on her paper. The student was very pleased with this interaction and was able to complete her paper. Aside from a few organizational and grammatical issues at the end of her writing that we had to address, the paper was very captivating. The student user was greatly appreciative and even stayed awhile to talk to me about her semester and family life.

—‘James’

Such “A-ha” moments, enabled in a Writing Center where everyone present is able and encouraged to speak to everyone else, have been the payoff of the last several years of hard work in changing tutors’, instructors’, and students’ perceptions of writing tutoring. But there have been and continue to be struggles, and the tutors have been more than willing to share their critiques of the approach, as well.

So far I have enjoyed working with this format. I'm a little nervous about the possibility of having too many students at once who need help and not being sure how to balance helping all of them. What if I can't think of something for one of them to work on while I help the other?

—Hannah

Some students come to the center because their teacher requires it; others come just because their teacher simply encourages it. If we could get more teachers more educated about what exactly the writing Drop-In Lab is, then I think we'll see more of these objectives met. Students would be more encouraged to start writing up in the lab rather than just handing their paper over to proofread.

—Michelle

I think that whenever the concept of a drop in lab is fully understood, a more organic writing process could occur in this drop in labs. I think by letting people know the concept of the drop in lab, people will be aware of it and start using it more as a way to create a well-structured essay instead of a place to revise a finished document.

—‘Esther’

The drop in lab creates a nice, casual atmosphere, and students don't always need as much intense help. This is nice as a tutor, and I can imagine it makes the writing process less stressful. I do think we need to be reminded that circulating, and letting students do some work on their own, can be really effective, and whenever possible, we should be using that strategy. And I think we need help figuring out how to encourage students to work together, and how to facilitate those interactions.

—‘Jill’

Responding to the concerns voiced here will be the explicit goal of future semesters.

Looking Ahead

Upcoming semesters in the Writing Drop-In Lab will be marked by further training, with an eye towards providing the tutoring staff with an even broader range of tools for working with groups of writers. They will also be marked by further outreach. Increasingly, students are arriving at the writing center earlier in the writing process and are prepared to share their own work and to read other students’ writing. The major goal of future semesters will be to educate faculty, who continue to refer students to the Drop-In Lab almost exclusively to have completed drafts reviewed, on the other possibilities of the center: for students to write, to collaborate with their peers, to participate on both sides of the review process, and to engage in a conversation around writing.

The survey results, as well as the tutor comments provided above, both indicate that the program has been highly successful in meeting the goal of engaging tutors with students’ processes for writing. They also, however, indicate a high degree of variation among the tutoring staff, with some tutors taking frequent advantage of opportunities for peer collaboration, and others doing so far less often.

Informal discussions with the tutors point to three main reasons for this issue. First, the use of collaborative strategies requires a critical mass of students who are engaged in the same or similar assignments. When there are five to ten (or more) students in the lab, as is typical during the busy mid-day period, this threshold is readily crossed. During slower times, the prerequisite number of students is reached far less often. One reason, then, for the high number of tutors who do not take advantage of collaborative techniques is that they work at slower times and have less, if any, opportunity to use them. Second, tutors who work together in the Drop-in Lab have often established roles for themselves in the lab: in shifts where two or three tutors are working, one or two of the tutors will circulate among students, while another tutor assumes the role of group facilitator, directing students into and working with groups of students working on related tasks. These roles, while informal, seem to be persistent, such that over time a tutor falls into a more or less permanent role of circulator or facilitator. Third, it appears to be the case that, in some instances, tutors are clear on the goals of the strategies that they are being asked to make use of, but they are simply unclear on or unpracticed in the nuts and bolts of how to apply them, and aren’t confident enough in making use of them to direct students into groups.

The first of these, to the extent that it can be addressed, will be responded to in scheduling, attempting as much as possible to ensure that all tutors have at least some hours during peak periods. In the case of the second, while I don’t believe that the system that’s arisen is a bad one (and may in fact be quite positive in that it draws on the unique strengths of individual tutors), we will be encouraging all tutors to take on the role of group facilitator periodically so that the entire staff is well versed in all relevant approaches. The third, to me, indicates that the trainings that tutors have received on collaborative techniques have erred too far on the side of theory. In future trainings, it will become a greater priority to show tutors models (through observations of the Drop-in Lab, or demonstrations staged by veteran tutors) of collaborative approaches being applied, and to give them practice applying them in mock tutoring scenarios. We will also be working to create more opportunities for in-class peer review workshops, so that more tutors can be given the chance to become more fluent in the approach in a more formal, structured environment.

To writing center directors seeking to implement the peer-interactive model at their own universities, I’d offer one piece of advice above all else: involve the tutors early and often, creating a sense of investment in and ownership of the model during the planning stages. Our center has arrived over time at a very high degree of buy-in to the peer-interactive model on the part of the tutors, who are the most important stakeholders in the format, but I believe that the process of getting to where we are now could have been greatly eased by more consciousness early on of how the tutors might feel discomfited by the shift away from the familiar, cozy environment of the individual appointment, and how this might have been avoided by creating more enthusiasm around the model. In the Fall of 2009, I thought that the best path towards full adoption of the model would be to explain the methods associated with it, and to coach the tutors on how to implement them. I’ve since discovered, in discussing the peer-interactive writing center approach in forums of interdisciplinary faculty and of WPAs at UNM and elsewhere, that I wasn’t giving my audience enough credit: nothing needed to be explained. The principles of the peer-interactive center are intuitive. Presented with the nearly universal goals for writing center work that are outlined above, and invited to think through the possibilities for how writing centers can more effectively meet them, people tend to arrive at much the same conclusions that we have about which tools are best to use within a center that fully aligns its practice with its theory.

The intensive feedback that students receive in individual writing appointments is invaluable for student writers, and individual appointments clearly have a place in a writing center that seeks to meet its students’ needs in a variety of ways—indeed, in many cases, an individual appointment is an ideal follow-up to a session in the Writing Drop-In Lab. However, individual appointments are often characterized by an inherently unequal dynamic between the tutor and the tutored, such that the tutor is the authority on writing and the student user is a recipient of knowledge. The transfer of such knowledge is one important part of what writing centers do. Just as important, however, is for writing centers to promote their student users as reviewers and commenters of their own and others’ work, validating a relationship to writing that will serve them throughout their academic and professional careers well after their direct relationship to the center has ended. The peer-interactive writing center approach, as exemplified by the Writing Drop-in Lab at the University of New Mexico, presents a model for doing so.

Appendices

Both appendices are handouts, so they are delivered as PDF only.

Notes

-

See The University Writing Center at Texas A&M, which offers a workshop for faculty on leading peer reviews, The Center for Writing at the University of Minnesota, which enables electronic peer reviews for students through their online writing center, and The Writing Center at Pacific Lutheran University, which facilitates peer review workshops for specific courses. (Return to text.)

-

See The Writing Center at the Boston University Educational Resource Center, which encourages group tutoring for students working on group assignments, The Writing Lab at The Citadel University Academic Support Center in Charleston, SC, which takes advantage of small group sessions to increase tutor/tutee interaction, and The Chaffey College Writing Center, which offers group sessions as a service to faculty who wish to refer a subset of their students to a guided session on a set topic in writing. (Return to text.)

-

See, for example, The Writer’s Center, a non-profit on Bethesda, RI, which caters to the needs of professional writers using on-line and in-person workshopping sessions in which participants review and critique one another’s work, and the Midwest Writing Center, a program funded by the Illinois Arts Council that provides a forum for professional and amateur creative writers to share their work. (Return to text.)

-

T-tests for sets of responses for each question were significant, p < .05. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Elbow, Peter and Mary Dean Sorcinelle. “How to Enhance Learning by Using High-Stakes and Low-Stakes Writing”. McKeachie's Teaching Tips: Strategies, Research, and Theory for College and University Teachers. 12th ed. Eds. Svinicki, Marilla and Wilbert McKeachie. Belmont, CA: Wadsworth, 2005. 213-233. Print.

Elbow, Peter. “Write First: Putting Writing before Reading is an Effective Approach to Teaching and Learning.” Educational Leadership 62.2 (2004): 8-14. Print.

Joyner, Michael. “The Writing Center Conference and the Textuality of Power.” The Writing Center Journal 12.1 (1991): 80-89. Print.

Lunsford, Andrea. “Collaboration, Control, and the Idea of a Writing Center.” The Writing Center Journal 12.1 (1991): 3-10. Print.

Lunsford, Andrea, Lisa Ede, and Corinne Arráez. “Working Together: Collaborative Research and Writing in Higher Education.” Modern Language Association Profession (2001): 7-15. Print.

Lunsford, Andrea and Lisa Ede. “Collaboration and Concepts of Authorship.” PMLA 116.2 (2001): 354-370. Print.

Macrorie, Ken. “Words in the Way.” The English Journal 40.7 (1951): 382–385. Print.

Murray, Donald M. “Teach Writing as Process Not Product.” The Leaflet (Nov 1972): 1-11. Print.

———. “The Listening Eye: Reflections on the Writing Conference.” College English 41.1 (1979): 13-18. Print.

North, Stephen. “The Idea of a Writing Center.” College English 46.5 (1984): 433-46. Print.

Soven, Margot Iris. What the Writing Tutor Needs to Know. Boston, MA: Thomson/ Wadsworth, 2006. Print.

Spigelman, Candace and Laurie Grobman, Eds. On Location: Theory and Practice in Classroom-Based Writing Tutoring. Logan: Utah State UP, 2005. Print.

Stanger, Carol. “The Sexual Politics of the One-to-One Tutorial Approach and Collaborative Learning.” Teaching Writing: Pedagogy, Gender, and Equity. Eds. Cynthia L. Caywood and Gillian R. Overing. Albany: SUNY UP, 1987. 31-44. Print.

Strauss, Susan and Xuehua Xiang. “The Writing Conference as a Locus of Emergent Agency.” Written Communication 23 (2006): 355-396. Print.

Walker, Caroline. “Teacher Dominance in the Writing Conference.” Journal of Teaching Writing 11.1 (1992): 65-88. Print.

“The Peer-Interactive Writing Center at the University of New Mexico” from Composition Forum 25 (Spring 2012)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/25/new-mexico-interactive-wc.php

© Copyright 2012 Daniel Sanford.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 25 table of contents.