Composition Forum 25, Spring 2012

http://compositionforum.com/issue/25/

“For rhetoric, the text is the world in which we find ourselves”: A Conversation with Victor Villanueva

Abstract: In this conversation, Villanueva reflects on his major goals as a scholar, teacher, and an administrator. He argues that his main concerns emerge from negotiating his various "insider" and "outsider" roles and personal experiences that have been shaped both by cultural meanings and cultural theories. Ultimately Villanueva rejects being called a "boss compositionist" and instead reiterates his commitment to being a student of rhetoric.

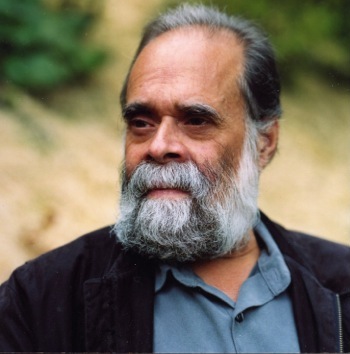

To introduce Victor Villanueva is to point to his own words; the best overview comes from his Bootstraps: From an American Academic of Color (1993) for which he won NCTE’s David Russell Award for Distinguished Research in the Teaching of English. Born in Brooklyn, Puerto Rican, a high-school dropout, a community college student, a Vietnam-era vet, a Ph.D.—Victor has a rich and diverse background that communicates itself most eloquently in his equally rich and diverse work: numerous edited or co-edited books including Cross-Talk in Comp Theory: A Graduate Reader (1997, 2003, 2011); Latino/a Discourses: On Language, Identity, and Literacy Education (2004), with Michelle Hall Kells and Valerie Balester; Rhetorics of the Americas: 3114 BCE to 2012 CE (2009), with Damián Baca; and the forthcoming A Language and Power Reader: Representations of Race in a Color-Blind Era, with Robert Eddy, and On Language and Value: Political Economies of Rhetoric and Composition, with Wendy Olson and Siskanna Naynaha. He has authored numerous book chapters and articles on race and rhetoric, writers of color, basic writing, colonialism and writing, and various social and political connections to composition and rhetoric.

In addition to his scholarship, he has contributed much to the field of composition and rhetoric through his teaching, beginning at Big Bend Community College in Moses Lake, Washington; and moving to the University of Washington, the University of Missouri-Kansas City, Northern Arizona University, and Washington State University, where he earned the honor of being named Regents Professor. Most recently he accepted the post as Head of the English Department at Auburn University. He has been honored with numerous guest editing posts, visiting professorships, keynote addresses, and awards of excellence for his scholarship and teaching.

I was pleased to be Victor’s student when he first arrived at Washington State University’s English Department and was very happy that he was willing to complete this interview even as he was beginning his new post at Auburn. Our conversations took place over email between late July and October 2011. I have rearranged the questions and answers to follow logical order, though I tended to send Victor three or more questions at a time and, after receiving his replies, would send three or more responses and additional questions. Thus our conversation became somewhat looping, intertextual, and interlaced with my nagging reminders and his kind words alternating between assurance and apology. I thank Victor, as always, for his generosity with his time and his willingness to continuously give to the field to which he has already given so much.

Ellen Gil-Gómez (EGG): Hi Victor, just some openers to start off … first, the most important: what do you currently have playing on your iPod?

Victor Villanueva (VV): Well, because I’m in the office, I’ve got Pandora on, rather than iTunes on my iPhone/iPad. I’m listening to Ralph Towner Radio—acoustic jazz guitar stuff; I don’t have to play it loud; and I like it.

EGG: How has your move to Auburn been? Are there any particular changes you were looking for in terms of your professional life?

VV: So far the move has been great. I’m enjoying the sun. I don’t seem to have allergies here (the second time in my life; the first time was during a stay in Costa Rica; archeologists have uncovered that the Taíno indians, which are surely a part of my ancestry and genetic makeup once lived in this area then joined with the Creek Indians when the Europeans started to take over). And the people have been wonderful so far. Professionally, it’s a break from the primacy of graduate student work and the classroom. After exactly thirty years, I’ve needed a break.

EGG: Can you give readers an overview as to what you feel is most important from your background as it relates to composition?

VV: This is a simple matter, really. Although each of us—all of us—have unique backgrounds that affect how we go about our jobs, there remains a scarcity of folks with backgrounds like mine in front of classrooms, in the pages of our publications, or in academic administrative posts (and I say “academic” administrative posts, because I think the majority of administration in universities aren’t directly connected to the day-to-day of academics—that’s mainly the job of department chairs or heads). There is a new generation of compositionists coming up now with backgrounds similar to mine. But their numbers continue to remain few. So, as always, those—the overwhelming majority—who wish to do well by students of color and from poverty might glean something from the perspective I provide, matters discussed in simple autobiography to theories of culture, representation, and political economies, all ways of coming to an understanding of those folks wishing to enter the academy or wishing to remain in the academy whose backgrounds are not typical (in terms of notions of race, or class as a cultural determinant, or class in the economic sense, or even class in the sense of having served in the military, which isn’t always primarily a matter of national loyalties but primarily (I’m not excluding the patriotic) economic. Thirty years, and even though I’ve met a few high-school dropout professors and a few combat veteran professors (though always commissioned officers), I’ve yet to meet another Puerto Rican high-school dropout, enlisted Vietnam Vet professor. I think it colors how one sees the job; and I hope that the work I do helps color how others see the job and consider how I come to those theories and theorists I am most drawn to.

And that ends this phase for now, I reckon.

EGG: Can you discuss some specific ways that your background—dropout, vet, Puerto Rican (not necessarily in that order!) has influenced you in the classroom—with both undergraduate and graduate students? What are the differences and similarities in these environments for you?

VV: I don’t really know how to answer this, because there is an inherent contradiction between the insider and the outsider when one has been in this profession for as long as I have now. I mean, my first impulse is to say that as the perennial outsider, I am always conscious of having to detail the political, of always having to foreground and contextualize, of having to assume that the matters that have given rise to my worldview are foreign to most of the students, maybe even all of the students, because I’m now older than their parents, often. I’m a man of the 1950s (born at the end of 1948) talking with students of the 1990s (the typical junior having been born in 1989). That makes for a whole lot of contextualizing. But it also makes for a whole lot of learning. I have to listen, really listen, to students, parcel out the experiential from the ideological among the students.

And I’m also the insider in ways that requires more and more foregrounding and contextualizing. I’ve become fully ensconced in the academy, having to remember that students don’t know a chair from a dean, an instructor from a full professor. I remember telling my mother that I had been promoted to full professor. Her response was to say “I thought you were already a professor.” So here I am having to articulate quite fully the workings of the world I’m in and having to articulate even more fully the worlds I came from and that still reside within me. At this point, I’m neither fish nor foul yet both.

EGG: How about the same in advising/administration roles?

VV: I think [the above answer], gets at a great deal of the advising role—from undergraduates trying to make it through the major to doctoral students. Where advising and administration come together, and where my successes in helping negotiate the system (and helps me in negotiating the system) comes from the degree to which a certain set of locations (geographic, cultural, class) have prepared me to understanding, intimately, the workings of bureaucracies. I grew up in a Catholic school, where priests, the brothers, the nuns, and the lay teachers adhered to a very strict order, where rules came down through the Pope, bishops, and pastors. Then a short time in business—the head of the computer room was in charge of the keypunchers (never mind that the computer guy was 18, me, and the keypunchers were women in their forties and older—one learns something about gender too). Then the army. No need to carry on about that particular bureaucracy. I entered business and the army at the lowest rung—a high-school dropout doing clerk work; a private—I left both as a part of middle management. Although it took me a while, when I figured out that “faculty and administration” meant the same as “enlisted and officers” or more directly “labor and management,” I knew my way around, a way around that did not begin with the presumption of entitlement. And I knew, especially with the help of Max Weber, that bureaucracies are built to weather crises and incompetent leadership, so that no crisis is catastrophic; they all pass.

EGG: Considering what you’ve said about the uniqueness of your background as an academic in the field, what specifically attracted you to the field of English generally and/or composition/rhetoric in particular when you first began your studies? Did you have particular goals when you entered as an undergraduate? Or graduate student? Or beginning instructor?

VV: Oh, this question actually get played out quite completely in Bootstraps. So here’s a truncated version. The short version is that after the Army, I went to the local community college to get a regular high school diploma, because it was obvious that the GED carried no weight in the labor market. To the degree to which I thought of a major, I went into Chemistry, with a plan that maybe I could become a pharmacist. I thought about pharmacy because I aspired to a small-town life and a job with some prestige and some autonomy. But I had to take English 101 and 102. And while I was very good at math and could solve the problems presented in Chemistry classes, it was the fun of reading and discussing what we read that stuck with me. Then, a section of 102 is devoted to “AfroAmerican Lit,” and I realize that I had something to contribute, an understanding of the text that the teacher (a very nice man) didn’t have. So—an English major. Then graduate school because I had decided to stay in college until I got kicked out (I started at the community college in 1976; I got the Ph.D. in 1986; and I’ve been a professor since 1985—haven’t been kicked out yet). In graduate school, I accidentally took a course on rhetoric. The class’s title was “Theories of Invention.” Somehow I thought it was an American Lit class, because I remember that Benjamin Franklin would sign his name followed by “Inventor.” And that was all she wrote. It was the realization that I had been a rhetorician all my life; just didn’t know that’s what I did. I read and thought about language and the world. The difference to me between literary criticism and rhetoric is what constitutes text. For lit, the text is the book in your hands; for rhetoric, the text is the world in which we find ourselves. I still love what I do.

EGG: What’s your view in terms of how the world of composition has welcomed/changed (or not!) students/faculty/administrators from various “outsider” backgrounds? Any specifics come to mind?

VV: When I was a graduate student, I thoroughly enjoyed the writing of James Sledd and his tirades for bidialectalism (though eventually, I’d be called one of the “boss compositionists” by Sledd; he knew my place in the bureaucracy, but not what I wrote about, apparently). Of late, I’ve enjoyed reading Bruce Horner and John Trimbur taking the conversation from dialect to language, arguing against the rigid monolingualism of the composition classroom. Spanish enters into some of our English articles (some by me); American Indian languages; surely some of the ways of African American Language enters the discourse; discussions from Asians, Asian Americans, Hawaiians (but not much from Filipinos and Filipinas, I notice). Vershawn Young, in terms of people of color; Suresh Canagarajah for speakers of other languages coming to English, both making the case for “code meshing,” Vershawn’s term. We are all heard. We are all accommodated. Our discussions arise and are entertained by the majority of our profession, it seems. But we are institutionally constrained. So that any rhetoric for first-year comp or any handbook we see might bring up such things, but all of it to tell us how best to recognize those various ways with words in order to teach the one-true-way-with-words. In the end, because our voices are not fully heard across the institution, because we must comply with “the language of wider communication,” to borrow from Joshua Fishman, in institutions that have departments of “foreign” languages rather than departments of languages and cultures, the real change, the real appreciation of our many Englishes and other languages continues to elude us. We have changed in the quarter-century that I’ve been a part of this profession; what we do when we walk into a comp classroom has not, at least not significantly.

EGG: It’s quite interesting to me how you discuss the constant negotiation of insiders/outsiders on so many levels. What do you make of the enormous differences that you just mentioned regarding how dialects/Englishes/etc. are more and more explored by compositionists versus the “institution” or should I say “business” of composition? Is this just another level of “boss and labor” in your view? Or is something else going on?

VV: Oh, I’d say that this gap between language fairness in our discussions and language oneness in our day-to-day institutional labors has to do with the business of business. In other words, this is less boss-and-labor than the nature of capitalism writ large. Our scholarship is always concerned with justice and equity, but we are given to having to work within an inequitable system, a system that by necessity has to seek out profits and serve the overall political economic hegemony. I really like the rhetoric of profit for universities and other such entities—“not for profit.” That’s not “non-profit” but an assertion that the main motivation isn’t profit but profit remains nevertheless. The university—despite its wonderful ideals for the betterment of society in all kinds of ways—has to compete in a global market. For the moment, that global market’s hegemon is the U.S. with its de facto official language. We can speak of the ways of teaching English that recognize there is no inherently superior dialect or language; we work within a structure that says “no inherent superiority” yet asserts “an economically convenient superiority.” We make ourselves feel better about the contradiction by saying we’re helping students to succeed in an ostensibly English-only institution. We can adopt Joshua Fishman’s “language of wider communication.” But that’s really a euphemism, a way of skirting around power relations. We’re really caught up in the rhetoric and the discourse of the global political economic verity of the moment.

EGG: Do you think there are any dangers to seeing yourself as always both insider AND outsider? Are you fooling yourself about your own power in the field? Your own “boss-ness”? Put another way, are you wary of emphasizing the outsiderness to the detriment of insiderness?

VV: Sure is a loaded question, eh? [As I mentioned before] James Sledd (from another generation of Comp) once included me among his “Boss Compositionists.” I was mildly insulted, because my work had to do with racism, colonialism, hegemony and all that resistance stuff. But what with Cross-Talk and being somewhere in the Cs hierarchy at the time (maybe 12 years ago), he wasn’t wrong. I remain, however, sometimes taken aback about my status in this discipline because I never set out to be the first at anything, just to say stuff that occurs to me as I read and talk with folks in our business and in other fields (and my favorite autodidact—my wife, Carol, whose background is in history but who extends beyond that) and thereby learn of new things to read and think about and write. So maybe I have to say “yes and no.” I know I have status. I never know really about the nature of that status. I know I’m a big fish in this little rhet-and-comp pool. But I never know the degree to which it’s because I’m a fish of a different color. And it’s in the not knowing that I remain relatively safe from arrogance (though I have my moments) or from complete disassociation with my co-workers, including those whose work is outside my range of interests. This is the stuff of identity politics, the reason why identity politics finally falls short, because there is a tacit insistence to choose in identity politics, but it ain’t never that easy. Am I wary of emphasizing the one over the other? Hadn’t thought of it till you asked. Off the top, yes, safely so, I hope.

EGG: It seems to me that you are emphasizing more and more the importance of personal intimate spaces, languages, cultural meanings, memory, etc. Is this an intentional shift as you gain more and more of the trappings of “insiderness?”

VV: This is more a matter of age. Really, I’ve never been far from intimate spaces, having blended the personal with the generalizable and maybe even global since my second publication, the one that appeared in English Journal back in 1987. But I know my writing has tapped a little deeper into the soul these days, as a parent dies and another starts to leave, her memory fading, and as children grow and leave, and as my own mortality confronts me a little more directly, Mortality in my face—literally as well as metaphorically. So I recognize the advantage I do have of my insiderness, and I use it to leave a trail that is deeply personal but which I continue to hope is a trail that others will tread and even find familiar in some sense or other.

EGG: In a very real way, being “Boss” can be different when you intend to be one, versus when you don’t intend to. I mean, if you are looking for power/influence, even for “good” reasons, it seems that your work can be more easily uprooted from its intent. However, when you find yourself being referred to as “Boss” you can still choose to not accept its benefits and write or work against it. Is that something you’ve tried to do?

VV: Thing is, when you’ve been the head of a national organization, director of comp, chair of a department (twice!), a director (also twice), an associate dean, what else can you be but Boss? And surely there has been a certain intention to my being Boss, sometimes explicitly, sometimes more passively (being asked and not saying “no”). And the “good” reasons were always somehow not so good—ambition and lucre (well, maybe “lucre” is a little harsh; let’s just say “pay increases”). Boss, yes. My problem with being “Boss Compositionist” was with who was saying it, someone with whom I tended to agree (or at least to be grateful for, for his manner, his voice, his well-studied curmudgeonliness). I didn’t like being cast as his opposition, knowing he knew nothing of my work, only of my job, but that my work was more aligned with his than not. Because whatever Boss-ness I’ve sought and gathered, that was the job, jobs carried out with honesty and kindness as a rule, but not the Work. So I’ve kind of seen a thin membrane that separates the Job from the Work, not a subversion of the Job but emotionally, at least, transcendent of the Job, with the Work having the greater meaning for me and with the hope that it carries the greater meaning for my fellow fish in this small pond.

EGG: I can remember being labeled, at various points in my education and career, as a “troublemaker” when what I wanted to do was study work by lesbians of color. It was clear to me early on that my interests said more about where I was studying or working than my intent to be disruptive. But I guess, as you mention earlier, some topics are always in opposition to the unspoken role of the university as part of the system rather than as a way out of it. What labels have you been given that you are uncomfortable with? Alternately, are there any that you embrace?

VV: Oh, I’ve been called Trouble (“Here comes Trouble!”) a lot. Even just last week. But it’s always been said—or at least I’ve accepted the label as being said— with affection. And about the only label I’ve resisted has been being characterized as a Marxist. I tell folks who call me that that I’m not a Marxist; I’m a Catholic. And folks laugh. But I don’t know that they understand what I mean. I assume because folks associate Marxism with atheism, that that’s what they think I’m getting at. But I’m thinking more along the lines of Kenneth Burke’s “terministic screens,” that the label “Marxist” defines a little too restrictively. The label confines, limits. There is too much of a presupposition of what I think or believe. We’re back to the identity politics box. Marx is really smart. I tend to like a good deal of his writings. Gramsci knocks me out. There are parts of all of their derivatives—derivatives and expanders—that I like, admire, refer to: Althusser, Raymond Williams, Stuart Hall, Erik Olin Wright. And there are many others: Karl Polanyi, Arrigi, Wallerstein, Braudel—who fall out of yet might be attached somewhat to such a label. And there are still others. In a comp class, I can use Aristotle or Elbow. What matters to me is a kind of conceptual or philosophical consistency rather than a School (especially one that starts to take on religious overtones)—my religion is Catholicism (I tried being agnostic but felt guilty, is a standard joke of mine; but it’s also true), not Marxism.

As for a label I embrace, it’s Scholar. It’s connotation is honorable—a serious thinker. Its roots are accurate—a student. I aspire to seeing myself as a Scholar in that most honorable way at some point in this life; I’m happy to continue to be a student until (if ever) I achieve what I aspire; and I feel honored when I’m referred to that way (even if I don’t think I’ve quite earned the title yet).

EGG: You mentioned your “mortality—literally and metaphorically” earlier. Do you feel you have a lot of work to do? Have the goals of your work changed? What do you see as the greatest current challenge to the field? Or for that matter your greatest hope for change or improvement?

VV: “The field” is tough, because we embrace at least two disciplines. I’m kind of proud about being associated with the link between political economy and rhetoric. I haven’t done anything substantial with that connection, but I see others who are embracing it, realizing that power cannot be detached from the rhetorical except when it’s coercive power (and even that can come into question). Comp, I think, continues to find its way. But it’s a young field. As for work to do—yep—both broad (as in the rhetoric of pol econ or the pol econ of rhetoric) and very personal (as in the rhetorics of the Taíno). There is always the Work.

Works Cited

Baca, Damián, and Victor Villanueva, eds. Rhetorics of the Americas: 3114 BCE to 2012 CE. New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2009. Print.

Kells, Michelle Hall, Valerie Balester, and Victor Villanueva, eds. Latino/a Discourses: On Language, Identity, and Literacy Education. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook-Heinemann, 2004. Print.

Villanueva, Victor. Bootstraps: From an American Academic of Color. Urbana, IL: NCTE, 1993. Print.

Villanueva, Victor, and Kristin L. Arola, eds. Cross-Talk in Comp Theory: A Graduate Reader. 3rd ed. Urbana, IL: NCTE, 2011. Print.

Villanueva, Victor, and Robert Eddy, eds. A Language and Power Reader: Representations of Race in a Color-Blind Era. Forthcoming 2012. Print.

Villanueva, Victor, Wendy Olson, and Siskanna Naynaha, eds. On Language and Value: Political Economies of Rhetoric and Composition. Logan, UT: Utah State UP, forthcoming 2012. Print.

Interview with Victor Villanueva from Composition Forum 25 (Spring 2012)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/25/victor-villanueva-interview.php

© Copyright 2012 Ellen M. Gil-Gómez.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 25 table of contents.