Composition Forum 37, Fall 2017

http://compositionforum.com/issue/37/

Getting ‘Writing Ready’ at the University of Washington: Developing Metacognition at a Time of Academic Transition

Abstract: Within the field of Writing Studies, metacognition is rapidly being recognized as essential for the effective transfer of knowledge across contexts. This program profile describes a pre-college writing course at the University of Washington that builds metacognition, confidence, and fluency in writing. Through program evaluations, student surveys, and instructor feedback, this profile describes how the course has evolved over the past decade, how students and instructors experience the curriculum, and reflections and recommendations for instructors considering introducing metacognitive practices in their own writing courses.

Introduction

Recent composition research has highlighted the importance of metacognition in helping students transfer and transform writing knowledge across learning contexts (Beaufort; Nowacek; Reiff and Bawarshi). Although this fuzzy concept (Scott and Levy) is recognized as central to critical thinking, self-directed learning, and the ability to apply prior knowledge to new learning situations, writing researchers and teachers are only beginning to understand how metacognition can best be researched (Driscoll and Wells; Gorzelsky et al.; Negretti and Kuteeva; VanKooten) and the optimal locations and methods for teaching metacognitive practices. This program profile describes a writing course that explicitly focuses on the development of students’ metacognitive practices, the University of Washington’s English 108: Writing Ready. This pre-college writing course for self-described “underprepared” writers cultivates students’ metacognition through self-reflective writing and learning about learning.

Generally defined as “thinking about thinking,” metacognition is a complex concept employed by researchers in many fields, including education, psychology, neuroscience, and learning sciences (Scott and Levy). Researchers generally agree that metacognition consists of two key components: first, metacognitive awareness, or awareness of one’s own cognition, and second, metacognitive regulation, or the ability to regulate one’s thinking and related practices (Hacker; Negretti and Kuteeva; Schraw; Scott and Levy; Sitko). Although metacognition is a part of normal cognitive development (Kuhn and Dean), students do not necessarily develop a robust set of metacognitive practices without explicit instruction and practice (Schraw). In fact, many college students enter the university without the flexible learning practices necessary for their ongoing success (Ambrose et al.; Moore et al.; Sommers and Saltz; Wardle). Recent studies of metacognition in the developmental writing classroom (Pacello), second language writing classrooms (DePalma and Ringer; Negretti and Kuteeva), and the first-year writing classroom (VanKooten; Yancey et al.) indicate that metacognition can be cultivated in the writing classroom to the benefit of students’ writing and their learning in general. Already, classroom practices such as reflective writing and self-assessment have been shown to strengthen students’ metacognitive awareness. Additionally, classroom practices such as teaching students to use feedback for revision and encouraging them to use campus resources can strengthen their metacognitive regulation.

Although these classroom activities are important ways to develop students’ writing skills and metacognitive practices, research indicates that integrating metacognitive practices throughout the curriculum deepens students’ understanding of their own writing and enables them to better transfer writing skills across contexts. In one such study, Kathleen Blake Yancey, Liane Robertson, and Kara Taczak challenge readers to explore metacognitive curricula that bring together structured reflection, vocabulary about writing and learning, readings about writing and reflection, and opportunities for students to develop their own relationship with writing.

This program profile explores the decade of Writing Ready course development, which, like Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak’s recent Teaching for Transfer curriculum project, has a curricular focus on students’ metacognitive development through writing instruction. Set in the month before incoming students officially matriculate to the university, the University of Washington’s English 108: Writing Ready attracts self-described underprepared writers through its focus on writing and learning. Developed in response to complaints that incoming students lacked writing skills, the Writing Ready curriculum focuses on developing students’ confidence in writing, expanding their comfort and fluency composing longer texts, and supporting students’ development of robust metacognitive practices.

In this program profile, I first explore the context that led to the creation of such a course and what it looks like today. Second, I describe the current curriculum, including the key course assignments and curricular materials shared across the twenty sections of Writing Ready. Third, I analyze program assessment materials—including student course evaluations, instructor reflections, and a follow-up student survey—to shed light on how the course is understood by students and faculty alike and explore areas for further improvement. Finally, I analyze Writing Ready instructor feedback to reflect upon the course in practice and make recommendations for others who see the value of integrating explicit metacognitive instruction into their writing classrooms.

Context for Writing Ready

The University of Washington, Seattle, is a flagship public research university located just north of downtown Seattle. It currently has an enrollment of almost 45,000 students, including over 29,000 undergraduates. The university consists of 140 departments organized into 18 colleges and schools including the College of Arts and Sciences (CAS), College of Engineering, and Schools of Law, Business, and Medicine. In the fall of 2013 (when data was collected for this program profile), 28.3 percent of first-year students were first-generation college students, and international students made up 15.6 percent of the first-year class (Roseth).

The story of Writing Ready begins in 2002, when the Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences began receiving increasing numbers of faculty complaints that undergraduates lacked academic writing skills, such as one instructor’s complaint that student papers “had no verbs” (Webster, Personal Interview). In response, the Dean established a cross-disciplinary Undergraduate Curriculum Writing Committee charged with reviewing the undergraduate writing curriculum and presenting a proposal for improving it. This committee established the CAS Writing Program, with Associate Professor of English John Webster as Director, to coordinate a series of new writing initiatives to better support student and faculty needs—one of which was the Writing Ready course (Gatlin and Reddinger).

From the beginning, Writing Ready was a part of the Early Fall Start (EFS) program, which runs during the month-long break between Summer and Autumn Quarters (from mid-August to mid-September). Along with the Writing Ready course, EFS includes a number of one-month intensive Discovery Seminars taught by university faculty as engaging introductions to various disciplines. During the summer, incoming first-year students are invited to register for Writing Ready or one of the other Discovery Seminars{1} in order to get a “head start on college” (Early Fall Start - About). The course is considered part of Autumn Quarter, so students receive college credit for completion. Students who choose to enroll in an EFS course pay an additional fee (in 2013 tuition cost approximately $1400 for five credits) and students may choose to live on campus.

Developed as an alternative to existing grammar-based developmental writing courses, from the start Writing Ready focused on building students’ fluency, confidence, and comfort in writing through the development of metacognitive practices. In an interview with Webster about the development of the curriculum, he explains that his aim was to focus on the individual needs of each writer as opposed to the skill they as a group lacked (Webster, Personal Interview). He notes that many college writers lack both confidence and fluency in their writing: like any lifelong skill, writing requires practice in order to gain facility with the activity. By writing more frequently and more metacognitively, Webster argues, novice writers’ comfort and confidence with writing improves along with their fluency. Webster, along with then-Expository Writing Program Director Anis Bawarshi, approached Writing Ready course development by focusing on students’ metacognitive practices, asking the following question in their course proposal: “What would we like students to come to the college writing courses better able to do? In answering this question, we focused on the meta-cognitive skills students need if they are to perform effectively as college writers.”

Developing students’ metacognitive abilities, then, includes fostering students’ self-regulatory capabilities, or their ability to manage learning demands. Bawarshi explains this focus on metacognition in Writing Ready further: “we want students to think about what writing and reading skills they bring [to the class] and how they can build on [those skills] to perform more effectively as college writers” (personal email, qtd. in Gatlin and Reddinger). As it was established to develop students’ metacognition, confidence, and fluency in writing, Writing Ready has, from the beginning “encourage[ed] students to understand their development and potential as writers in the past (high school), in the present (the threshold of GIS 140), and in the future (the university)” (Gatlin and Reddinger).

In 2004, Writing Ready joined the EFS program as a General Interdisciplinary Studies (GIS) course with two course sections each enrolling 20 students, growing to three sections in 2005 and four in 2006 (Gatlin and Reddinger). Today, it is housed in the English department as English 108: Writing Ready{2}. It is the most popular EFS course, with overall enrollments usually ranging from 250-320 students, with a target of 16 students per section. During the four-week course, students meet with their instructor for two and a half hours each day, four days per week. In addition, they are encouraged to visit office hours, the writing center, and many students also participate in campus activities, including international student activities and recruitment for Greek fraternities and sororities.

Along with the two current program directors, John Webster and Carrie Matthews, Writing Ready is taught by experienced graduate student instructors in the University of Washington from English Department programs, which include an M.A./PhD. in English Language and Literature (with concentrations in literary and cultural studies, in language, rhetoric and composition studies, and in textual studies), an MFA in poetry and fiction, and a Master of Arts for Teachers (of English to Speakers of Other Languages). Writing Ready instructors are chosen for their strong teaching abilities through a competitive application and interview process. All instructors participate in a three-day orientation that is preceded by an online conversation that asks them to read and respond to course texts, curricular materials, and pedagogical questions on an online discussion board. Both during orientation and during Writing Ready, the instructors are grouped into pods, or teaching cohorts of 4-5 instructors, guided by a Lead Instructor through training and providing support while the course is underway.

The Writing Ready instructors bring a variety of teaching experiences to the program. While the majority of the instructors have spent at least one year teaching in the Expository Writing Program (which includes expository writing, writing with literature, service learning, and a two-course sequence “stretch” version of first-year writing), many have also taught in the Interdisciplinary Writing Program (which includes first-year writing courses linked to the humanities, social sciences, and natural sciences). These instructors have extensive experience teaching a variety of composition courses to undergraduates at the University of Washington, whether in first-year writing or interdisciplinary writing contexts, or both. Although the Writing Ready course goals compliment the Expository and Interdisciplinary Writing Programs’ course outcomes, from the beginning it has been made clear to instructors that Writing Ready is not a mini-FYW course (Gatlin and Reddinger).

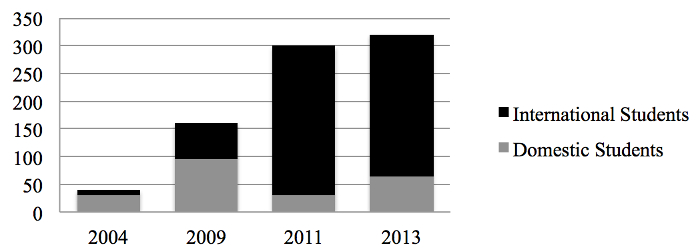

When it was first piloted in 2004, the majority of Writing Ready students were domestic students, but the course rapidly gained popularity among international and multilingual students{3}. With the drastic increase of international student enrollments at the University of Washington in 2011, ninety percent of students enrolled in Writing Ready had international student status. These large numbers of international student enrollments has continued to the present (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Student Entrollments in Writing Ready, 2004-2013

The disproportionate numbers of international students enrolling for the course has created some logistical challenges in course placement. Through trial and error, the program directors determined that, pedagogically, courses were the most productive when there were no isolated domestic students in a class of mainly international students. Therefore, the program directors ensure that there are at least three or four domestic students per class. In 2013, just under half of the course sections had a mixture of international and domestic students in class, while the rest of the sections had entirely international students. Instructors approach cultural diversity differently, depending on the student make-up of the courses.

With such a vast change in student population, Writing Ready instructors training began to incorporate more discussion of how to work with multilingual students, how to create community in diverse classrooms, and when and where to give instruction and feedback on grammar, while continuing to maintain the central course goals and assignment sequences. Over the past decade, Writing Ready has evolved into a space where self-described “underprepared” students become more prepared writers by engaging with their prior writing and learning experiences, performing and reflecting upon college writing practices, and by facing—and overcoming—difficulty through carefully-scaffolded complex learning tasks.

Course Curriculum

Building students’ metacognitive practices is a clear goal of the Writing Ready course, as the course goal statement used during instructor training states: “We want students to leave English 108 with more Fluency, more Confidence, and more Self-efficacy with respect to writing, reading and learning in English.” From the first day of class, Writing Ready is explicit in its motives to improve students’ fluency by writing a lot; build their confidence by becoming more metacognitive; expand their a vocabulary about writing and learning through the study of learning concepts; and support their development of strategies for using campus resources. The four-week course is built around two learning sequences: first, a two-week writing sequence that includes reflective and analytical writing about students’ past writing and learning experiences, and second, an interactive two-week sequence on learning that culminates in a group presentation on a learning question to a community of their peers (see Appendix 1: Major Course Assignments).

The first two-week sequence consists of three writing assignments, which ask students to engage with their learning memories in different ways. The first assignment is an in-class timed essay that asks students to give a “snapshot” of a “distinct moment” from their writing life. This enables students to recount and revise significant writing memories while acknowledging their emotional relationship with and attitude toward writing in general (Musgrove 1). The second assignment, My Writing Life, is a three- to four-page essay that builds from the first in-class “snapshot” essay, and asks students to “tell […] the story of how you came to be the writer you are.” In this essay, students are asked to describe two or three key moments from their writing lives, linking them together with a common theme. This essay becomes both social and instructive through self-assessment and peer review activities during the drafting process.

The third assignment, My Learning Profile—also a three- to four-page essay—asks students to use examples from their past experiences, but expands the focus from writing to all learning tasks, asking students to “tell me about yourself as a learner, using key learning concepts we have developed over the past two weeks and supporting your self-analysis by recounting three or four different events in your learning life.” This essay asks students to move from narrative writing assignments to analytical writing assignments that help them explore who they are as individual learners and what that means for their future learning. Students use vocabulary from scholarship on teaching and learning to analyze their personal learning moments. This self-appraisal activity helps foster students’ metacognitive awareness and articulate potential future learning strategies (Hacker 10). My Learning Profile, then, serves as a reflective moment where students remember and analyze prior learning moments, and it becomes a new learning memory where the student grapples with the meaning of those moments within a social context (Jarratt et al.).

Writing Ready has a specific set of grading criteria that is used across all sections of the course throughout the majority of the assignments. Developed by Webster, it is based on six broad criteria of good writing: central purpose, details, organization, fullness, fluency, and presentation (see Appendix 2: Writing Criteria). Students are introduced to these criteria in the first week and become well-acquainted with them early by using them to score a sample essay, participating in an in-class norming workshop, and using the language of the criteria in peer review. Additionally, when students turn in papers for instructor feedback, many instructors first ask students to score their essay according to the common grading criteria. Students are then asked to write down two areas that work well and two that require improvement. This feedback enables instructors to respond directly to students’ self-evaluations.

Inviting students to evaluate their own work begins a conversation that allows students to identify and respond to their own strengths and weaknesses as writers. Both instructors and students use the writing criteria throughout the course in order to develop students’ ability to independently evaluate their own writing. By inviting students to first evaluate their own writing, instructors are assessing the quality of students’ own self-assessment rather than the writing itself. Self-assessment is important for managing the emotions related to learning tasks, as well as managing the strategies necessary for successful learning strategy (Hacker 10). These writing criteria become shorthand for talking about writing in the Writing Ready classroom, while also informing the way instructors give feedback and the way students approach revision.

As students are writing about their own writing and learning experiences, they also read about the experiences of others: an excerpt from Kohl’s narrative essay, I Won’t Learn From You, Ramirez and Beilock’s scientific report Writing About Testing Worries Boosts Exam Performance in the Classroom, and Meyer and Land’s influential educational research article on Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge{4}.

Through these readings, students not only move from understanding narrative-style essays to analyzing academic articles, they also learn a vocabulary for talking about writing and learning. Establishing a set of vocabulary to talk about writing and learning enables students to critically engage with key concepts of learning and transfer (Wardle; Yancey et al.). The course readings are also accompanied by the Glossary of Common Learning Terms, written by program co-director Webster, which include contrasting concepts such as “long-term memory” versus “working memory,” “unlearning” versus “not-learning,” and “resistance” versus “resilience.” This vocabulary is used in class discussion, low-stakes writing assignments, and ultimately in their essays and class projects (Webster, A Glossary of Common Learning Terms).

The second two-week sequence focuses on researching a learning question and culminates in group conference presentations. Beginning with a Group Research Proposal and Presentation, students work collaboratively to research a question about learning that is interesting to them, conduct preliminary library research, and present their findings at a Conference on Learning. This assignment includes several scaffolded steps: forming a research question, conducting library research, writing a group presentation proposal, collaboratively creating a 10-12 minute group presentation (typically using Power Point or Prezi), giving a practice presentation in-class to their instructor and peers for feedback, and finally performing their presentation in an academic-style conference to other Writing Ready students. The final component of this sequence is a Conference Narrative and Analysis essay where students reflect upon their experiences working collaboratively to research and present their learning question and analyze one of the presentations they observed at the conference.

The final assignment in Writing Ready is a final portfolio, in which students compile all their writing from the course. On the final day of class, students write a final one-hour in-class essay reflecting upon their learning in the course. The reflection essay prompt asks students to “look back on all the work you have done these past four weeks,” noting that “[t]he more honest, thoughtful, and convincing you are about the challenges you will still be facing as you leave the class, the better positioned you will be to practice self-efficacy fall quarter.” This portfolio gives students the opportunity to collect and organize the work they have done over the past four weeks and reflect upon the impact it has had on how they think about themselves as writers and learners.

Assessing Writing Ready: Student Perceptions of the Course

The Writing Ready course has grown and adapted to a changing student demographic over the past decade and has been deemed a success by students and faculty alike. In this section, I analyze student perceptions of the Writing Ready course at the end of EFS and the end of their first year of college through CAS program assessment data and student Spring Survey responses. Understanding how students perceive learning experiences is an important factor in how actively students can utilize, or transfer, that knowledge (Bergmann and Zepernick; Jarratt et al.; Negretti; Pacello).

The CAS Writing Program annual program assessment of Writing Ready includes a course evaluation at the end of the term and a survey in the spring near the end of students’ first academic year (see Appendix 3: Assessment Questions). The course evaluation consists of two parts: the first part asks students to evaluate ten course components and evaluate their own confidence before and at the end of the course, while the second part invites students to respond to short answer questions about their learning during the course. For the purpose of this program profile, the 2013 EFS course evaluation and student confidence data were averaged by class and the short answer responses were coded by the CAS program assistant, and I was provided with the aggregate numeric results by category.

The 2014 Spring Survey included three separate parts designed to gather demographic background information about the students, ask questions about their Writing Ready experience, and examine what knowledge they used in their University of Washington coursework. Almost all of the questions were open-ended, allowing the students to respond to the question in their own way. Thirty-six students responded to this institutional research board-approved survey: an 11% response rate. Although this rate of participation is low, the rate is similar or better than previous Writing Ready Spring Surveys.

At the end of the course

Given the focus on building confidence and fluency in writing, it is not surprising that the program evaluation data indicates that students do feel more comfortable and confident writing after completing the course. When asked to self-report their confidence in their ability to meet the demands of college-level writing assignments at the beginning of the course and at the end, students across sections indicated that they felt more confident, with an average change of 1.59 points (see Table 1 below). Although all classes showed a net increase in confidence, the amount of increase ranged from class section to section, from just under 1 point to almost 3 points.

Table 1. Average Student Self-Reported Confidence Across 20 Course Sections (1-7)

|

Mean across sections |

Range of averages across sections |

Median of averages across sections |

|

|---|---|---|---|

|

Confidence before the course |

4.1 |

3.4 to 5.0 |

4.0 |

|

Confidence at end of the course |

5.6 |

4.8 to 6.6 |

5.55 |

|

Average Change |

1.59 |

0.8 to 2.9 |

1.65 |

These student-reported confidence scores show that students felt that the writing and learning tools they developed during the four-week course positively affected their confidence in their capabilities as college writers.

When asked to evaluate the main curricular features of the course, students indicated that interactions with their instructors contributed the most to their learning, whether through writing feedback or instructor conferences. Given the small class size and intensive nature of the EFS program, this is not surprising. However, students indicated that the group research presentation was similarly useful to their learning, rating the research and presentation project itself—as well as the accompanying group work—very highly (see Table 2).

Table 2. “How useful to your learning were each of the following?” (1-7)

|

Question rankings based on overall average values across 20 course sections. |

|

|

Question |

Overall Mean |

|---|---|

|

Your instructor’s feedback on your writing |

6.7 |

|

Conference(s) with your instructor |

6.5 |

|

Research and presentation project |

6.5 |

|

Group work for research presentation |

6.5 |

|

Workshop(s) on criteria scores and grades |

6.3 |

|

Essays/Papers reflecting on writing and learning strategies |

6.2 |

|

In-class discussion of student writing and writing strategies |

6.1 |

|

Scavenger hunt |

5.7 |

|

Free writes/in-class writings/informal writing |

5.6 |

|

Conferences with a writing tutor |

5.1 |

While students recognized that the course is primarily a writing preparation course, they also seemed to appreciate the metacognitive practices embedded in the curriculum. In particular, the self-assessment workshop on criteria scores, reflective essays, and in-class discussions of writing strategies were rated highly by most students. This indicates that students do perceive explicit attention to metacognitive practices to be useful to their learning.

The three activities that received lower—yet still “useful”—scores were the scavenger hunt, informal writing, and writing tutor conferences. Analysis of student written comments indicates that students’ perception of these activities ranged widely: for example, some students found the scavenger hunt to be a fun activity that helped them learn about the campus and build a spirit of camaraderie, while others found it unorganized and didn’t understand the purpose. Each year, the Program Directors and Lead Instructors work to clarify the objective of each of these activities, as there is general agreement among the directors and instructors alike that the value of these activities outweighs any negatives.

In addition to rating ten curricular features of the course, the 321 Writing Ready students were asked via short answer response questions to articulate the two most important things they learned during the course. Their responses indicated that both the academic and metacognitive practices were valuable to them. Students named academic writing practices (such as paper organization, research, argumentation, revision, quote integration, free-writing, and analysis) at least 263 times. Students noted metacognitive practices (such as confidence/self-efficacy, utilizing office hours, time management, metacognition, learning about learning/learning concepts, on-campus resources, self-evaluation, and critical thinking) at least 242 times across the short answer responses. That students identified both writing practices and metacognitive practices as valuable in their course evaluations is important for two reasons: first, because it demonstrates that students have developed a vocabulary to talk about not only their writing but also their learning, demystifying many college-level learning practices; and second, because robust metacognitive practices support effective writing practices.

At the end of the Academic Year

Although the College Writing Program has some statistics about student enrollments in Writing Ready, they do not collect specific demographic information about students’ linguistic histories and educational goals. One aim of the 2014 Spring Survey was to gather this demographic information. The thirty-six survey respondents included twenty-two students who identify as female and fourteen who identify as male. Twenty-five students lived in China at some point in their lives, while eight lived in the United States before enrolling at the University of Washington, three in Taiwan, and one student each in Ecuador and Korea. As a group, the survey respondents spoke seven languages: English, Chinese (including various dialects), Spanish, Korean, French, Italian, and German. The survey respondents also listed a wide variety of potential majors, from Neurobiology to Informatics, and Music to Environmental Science and Resource Management.

The Spring Survey asks students to recall the most important things they learned during Writing Ready. Like Bergmann and Zepernick’s study of student perceptions of learning to write and Jarratt, Mack, Sartor and Watson’s study of pedagogical memory, the spring survey questions are not intended to be an accurate representation of how students’ remember the course, but as a representation of their perceived learning during Writing Ready and the value that learning holds for them at the end of the academic year. Like the Course Evaluation data, students’ short-answer responses to the spring survey were coded for emergent themes.

Students’ Spring Survey responses indicate that students still feel that the most important things they learned in Writing Ready were academic skills and strategies (see Table 2).

Table 3. “After completing the course, what do you think are the most important things you learned in English 108?”

|

Academic Writing Skills/Strategies |

20 |

|

Awareness of Self /Metacognition |

8 |

|

Oral Communication (Peer work, presentation) |

8 |

|

Comfort/confidence |

4 |

|

Process/Revision |

4 |

|

Made Friends |

2 |

|

Reading Skills |

2 |

This perception that the academic skills and strategies taught during Writing Ready continued to be useful over their first year indicates that students maintained their awareness of effective writing practices as well as the vocabulary to name these skills and practices.

The majority of students listed academic writing practices as the most valuable things they learned, followed by self-awareness and oral communication. Many students’ short-answer responses show how these themes were interconnected. For example, note how one student describes learning study skills: “The way of study. I learned how to study generally, not just English itself. This course provides a pattern of learning that I will apply in University.” This student makes a distinction between learning more about the English language and learning the ways of thinking and learning necessary for success at an American university.

More than just skills and strategies, many students described a new orientation towards the challenge of college. One student writes that they learned, “College is doable and I can make it.” Another student writes that the most important thing they learned is to “Take steps and don’t hurry things. Progress takes time.” These lessons of persistence are important components of metacognitive awareness and regulation, and students seem to credit Writing Ready for this new orientation towards learning.

Students were also asked about how they transferred their learning in Writing Ready into their coursework over the first year. In contrast to the previous question that asked students about the most important things they learned in Writing Ready, students had a more difficult time specifying which skills and strategies helped in their coursework. Additionally, no students named metacognitive practices as helpful in their coursework (see Table 3).

Table 4. “What skills and strategies from English 108 have helped you in your coursework?”

|

Paper organization |

13 |

|

Writing process/revision |

8 |

|

No Response/Can’t think of any |

8 |

|

Library research |

4 |

|

Write concisely/clearly |

4 |

|

Self-assessment |

3 |

|

Oral communication |

3 |

|

Creative thinking |

2 |

|

Reading skills |

2 |

|

Fluency/Grammar |

2 |

|

Use writing center |

1 |

|

Use of analysis |

1 |

The lack of response by eight students suggests that even though students seem to value the writing and learning practices taught in Writing Ready, they might not immediately see the connection with their university coursework. The skills and strategies they did mention were largely related to writing, which suggests that students do make some connection with the writing practices taught during Writing Ready, but also that there may be a gap in how students understand the value of metacognitive practices for their university learning.

In addition to asking students about how they valued the learning done in Writing Ready and the skills and practices from the course that were useful during their first year, the Spring Survey asked whether they would recommend the course to a friend. The aim of this question is to encourage students’ reflection upon their motivations and experiences in the course. When asked “If you were going to recommend English 108 to a friend, what would you say about the course?” students were broadly reflective, with two themes emerging: the survey respondents recommended the course as an effective way to help students learn more about writing, and as a beneficial way to spend the transitional time to college. Often these themes were intertwined: one student recommended the course for both its content and timing: “I would say that it is an excellent experience and that it will make them productive over a very unproductive period of their life (between high school and college).” Another student describes the value of learning about new expectations about writing and learning at the university: “Change the traditional view of writing classes. Really helpful to prepare college courses.” Another student adds, “You learn a lot about yourself as a writer. I've never taken an English class where YOU yourself are the subject, so it was pretty interesting.”

The survey responses suggest that students came into the class expecting to learn about writing and, after completing the course, they believed that had. Moreover, the students felt that many of the writing practices they learned in Writing Ready were valuable in their later coursework. In addition to writing practices, students also recognized the value of the metacognitive practices taught in support of their ongoing learning. Although they did not name these metacognitive practices as valuable in their coursework over the first year, many students recognized the value of reflecting upon their learning habits during the transition from high school to university. All of the Spring Survey respondents would positively recommend the course to a friend.

Reflection and Recommendations

At end of Writing Across Contexts, Yancey, Robertson, and Taczak ask, “whether we should be teaching for transfer in the writing classroom,” and “whether we have any research showing us how to go about it” (149). This profile of Writing Ready supports their conclusion that incorporating the concepts, vocabulary, and practices associated with writing knowledge transfer can have a positive impact on students during their first year as college writers. In this final section, I will reflect on the recurring themes that emerged from this analysis of the Writing Ready program and the opportunities and challenges reported by instructors teaching the curriculum and offer recommendations for instructors and writing program administrators regarding incorporating metacognitive practices into writing curricula.

Emerging Themes

Teaching for metacognition, confidence, and fluency supports students’ transition to the university. Throughout student survey responses at the end of the course and the end of the first year, it is clear that students value Writing Ready for the important role it plays in supporting their transition from high school to college learning. Specifically, across all sections of Writing Ready, students report an increase in confidence in their ability to meet the demands of college-level writing assignments. At the end of the course, students name a large number of academic writing and metacognitive practices that they view as beneficial for their ongoing learning. At the end of the school year, students not only name a variety of Writing Ready writing practices that they have found valuable, but they also highlight the value of the class in supporting them during this transitional period for both social and academic reasons.

Teaching metacognitive practices creates a more active, engaged classroom environment. Students and instructors both reported high levels of satisfaction with their course experience. In focus group interviews and written reflections, many instructors indicated that Writing Ready energized their teaching in ways that persisted into their other teaching assignments. Instructor Charlotte{5} wrote, “What I love about [Writing Ready] is that I feel like I leave each summer of teaching with a whole new stock of strategies that I often appropriate and bring into my other classes as well. It is the most collaborative teaching work I do and [it] reinvigorates my pedagogical practices in ways I’m not even sure I can fully account for.” The Writing Ready curriculum has evolved to be both rigid and flexible; individually adaptable and collaborative. Instructors are free to adapt daily activities to their students’ needs, and can get both support and advice from the fellow members of their pod. Teaching metacognitive practices supports the creation of a classroom environment where instructors are excited to teach and invite their students to learn. Additionally, a curriculum focused first on self-exploration and second on learning about learning engages students in topics that are often at the forefront of their minds as they are moving between high school and university.

Challenges

Although the Writing Ready course is highly regarded among students and instructors, two specific challenges emerged from focus group discussions with instructors. First, the concept of metacognition itself remains fuzzy for many instructors. Although some instructors could easily give a brief definition of metacognition and describe how they and their students used it in the classroom, some instructors had a more difficult time defining the term and what it meant for their teaching practice. In one focus group discussion, two Writing Ready instructors articulated their discomfort with and resistance to this concept. First-year instructor Xander describes the challenge of using the term: “I think the weakest aspect of my teaching last year was effective use of metacognition.” Instructor Jared agrees, “To be honest, I don’t think I could tell you what metacognition means. It’s not a term that is useful to my area of study so I teach it and then I forget and I have to relearn it.” Although both Jared and Xander are honest about their discomfort with the term metacognition, both instructors indicated that, for them, the term was synonymous with reflection, which they felt was a valuable part of their teaching in Writing Ready and beyond. Jared acknowledges his resistance to the term metacognition, but recognizes the influence of reflective practices on his general teaching repertoire: “I think that reflection is really important, ironically. Though I hate the term metacognition, by working hard in [Writing Ready] to incorporate reflection more, it has enabled me to incorporate free writing and reflection in all the classes I teach.” The term metacognition, as introduced in the course, often did not seem relevant for instructors teaching in Literature, Creative Writing, and other disciplines; however, both student and instructor feedback indicated that by explicitly defining the term as a complex concept helped connect the learning concepts explored in the course and better bridge the two course sequences. Specifically, the term metacognition is most powerful when used as a broad concept linking reflection, self-assessment, self-efficacy, confidence, and many other learning practices.

In addition to the lack of clarity with the concept of metacognition, some instructors commented on the challenge of working with Writing Ready’s diverse student population. In a focus group conversation, returning-instructor Olga described some of the cross-cultural moments of the course as “navigating landmines” where different expectations and understandings of cultural, gender, and religious identities conflicted. Because the course is so popular with international students, Writing Ready often has a number of sections made up of entirely international students, while other sections have a mix of domestic and international students. The course curriculum does not vary across sections, as both students and instructors see the value of a course that focuses writing and learning through metacognitive practices for domestic and international students alike. However, creating space for instructors to work through cross-cultural conflicts in the classroom is essential.

The experience of one returning instructor describes both the challenge—and the value—of creating spaces where students with different cultural backgrounds can work across difference (Horner et al.; Lorimer; Lu and Horner). Returning-instructor Eleanor described her class of seventeen students as having ten students from China, one student from Central Asia, one from India, one Taiwanese-American, and four white Americans. Differences in how students from different educational backgrounds valued writing—and how they perceived writing errors—divided the class. In both her written reflection and focus group conversation, Eleanor described how these perceptions shaped the class environment:

Native English speak[ers] had a harder time disaggregating grammar and syntax (presentation) from central purpose. During that particular [writing criteria] norming session, a few louder, native English-speaking students had disparaged the sample paper we'd read for grammar and syntax errors. I think some of the non-native English speakers felt resentful that the paper was being dismissed on the basis of these errors and were eager to point out that central purpose and presentation are separate evaluative categories.

This incident highlights the tacit values students held for what “good” writing was—a difference which also highlighted cultural biases in the classroom (Matsuda). After this norming session, Eleanor described the classroom as tense. However, Eleanor reached out to the fellow instructors in her pod, and together they came up with in-class activities that would enable students to, as Eleanor described, “speak truth” to their experiences and also help students to develop active learning practices to negotiate across linguistic and cultural difference.

Because of the curricular focus on writing and learning, Eleanor and her fellow teachers were able to turn this and similar cross-cultural interactions into teachable moments. While this incident provided Eleanor with an opportunity for teaching metacognition with real stakes, it also allowed for an opportunity to connect the present activity to classroom readings and to students’ prior learning experiences and future goals. Eleanor noted in her written teaching reflection that this had a significant positive effect on the classroom environment, writing that students “began to approach each other as co-learners and co-contributors by the end of four weeks. One of the powerful things about [Writing Ready] is that since there are students who identify with so many cultures and identities, it can be a space to stage difficult conversations about how students see themselves and each other in the classroom.”

Creating spaces where tacit assumptions about writing and learning are exposed and where students have both the space and vocabulary to reflectively engage with past learning and future aspirations is an essential part of learning. This can feel uncomfortable for students and for instructors, and so there must be programmatic support for instructors to actively respond to classroom exigencies. In the case of Writing Ready, the curricular focus on metacognitive practices and the ability to share ideas within her supportive pod of instructors enabled Eleanor and other instructors to creatively respond to classroom challenges in a meaningful way.

Recommendations

When teaching for metacognition, emphasize how the concept brings many learning concepts together. Developing students’ metacognition was clearly an important component from the first Writing Ready course proposals; however, the concept is often used as a synonym for reflection. When introducing metacognition to faculty and teaching students metacognitive practices, many Writing Ready instructors reported success when introducing it as a complex concept that includes many other learning concepts. That is, metacognition is a two-part process that includes awareness of one’s learning practices (facilitated through classroom activities such as reflecting on prior learning experiences and recognizing the affective relationship students have with writing and learning) and the utilization of that awareness to regulate ongoing learning (developed through classroom activities such as practicing self-assessment, having students use on-campus resources, etc.). Framing metacognition as a broad concept that links the Writing Ready practices together might clarify the course objectives of improving students’ metacognition and their confidence and fluency in writing together. Being explicit in teaching not only a vocabulary of learning and writing terms, but how they relate to each other, helps students more articulately talk about their learning and writing experiences and improve upon them (Beaufort; Jarratt et al.; Nowacek; Yancey et al.).

When teaching for metacognition, utilize integrated, social practices. Because metacognition is a complex concept that brings together many learning activities, it needs to be integrated throughout a curriculum. Writing Ready instructors reported the most success when they integrated metacognitive practices regularly into classroom activities. Consistently practicing metacognition enables students to form good learning and writing habits. Xander compares this process with the musical concept of études, or “small compositions that are meant for you to hone a particular skill.” In his teaching, he invites students to regularly practice reflection just like a musician might practice études so that “You feel like you’re being a scholar, but really you’re creating the habit of having […] good practices. Because learning the word, they’re gonna forget that.” Integrating metacognition throughout the curriculum might include students regularly performing self-assessments of their writing skills using a common rubric, using reflective writing as a springboard for pre-reading discussions to activate prior knowledge, or the instructor verbally reflecting why they’ve chosen particular class activities or sharing stories of their literary or learning history (Zinchuk). Importantly, these metacognitive practices are both ongoing and social. Instructors and students engaging in collaborative discussions about different learning and writing processes on both a general and personal level normalizes metacognitive practices to the benefit of all involved.

Appendices

Notes

-

Discovery Seminars include topics such as space exploration, neurobiology, and travel writing. (Return to text.)

-

The full catalog course title is English 108, Writing Ready: Preparing for College Writing. On campus, it is commonly known by administrators, instructors, and students as English 108. In this article, I focus on the name of the course Writing Ready so that it is more accessible to writing faculty across institutions. (Return to text.)

-

There seem to be a number of factors contributing to this dramatic increase in international student enrollment. Most students indicate that they enrolled in the course on the recommendation of previous international students who enrolled in Writing Ready. (Return to text.)

-

Kohl, Herbert R. “I Won’t Learn From You”: And Other Thoughts on Creative Maladjustment. New Press. 2005.

Meyer, Jan and Ray Land. Threshold Concepts and Troublesome Knowledge: Linkages to Ways of Thinking and Practising Within the Disciplines. Improving Student Learning: Improving Student Learning Theory and Practice - Ten Years On, edited by C. Rust, Oxford Centre for Staff and Learning Development, 2003, http://www.etl.tla.ed.ac.uk/docs/ETLreport4.pdf.

Ramirez, Gerardo and Sian L. Beilock. Writing About Testing Worries Boosts Exam Performance in the Classroom. Science, vol. 331, no. 6014, 2011, pp. 211-213.

-

The names used in this study are pseudonyms, chosen by each of the instructors. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Ambrose, Susan A., et al. How Learning Works: Seven Research-Based Principles for Smart Teaching. 1st ed., Jossey-Bass, 2010.

Beaufort, Anne. College Writing and Beyond: A New Framework for University Writing Instruction. Utah State UP, 2007.

Bergmann, Linda S., and Janet Zepernick. Disciplinarity and Transfer: Students’ Perception of Learning to Write. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 31, no. 1-2, 2007, pp. 124-49.

DePalma, Michael-John, and Jeffrey M. Ringer. Toward a Theory of Adaptive Transfer: Expanding Disciplinary Discussions of ‘transfer’ in Second-Language Writing and Composition Studies. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 20, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 134-47.

Driscoll, Dana Lynn, and Jennifer Wells. Beyond Knowledge and Skills: Writing Transfer and the Role of Student Dispositions. Composition Forum, vol. 26, Fall 2012, www.compositionforum.com/issue/26/beyond-knowledge-skills.php.

Early Fall Start - About. www.outreach.washington.edu/efs/about/. Accessed 7 June 2016.

Gatlin, Jill, and Amy Reddinger. General Interdisciplinary Studies 140: Writing Ready: Getting a Start on Writing in College. 2005. Unpublished Manuscript. College Writing Program, University of Washington.

Gorzelsky, Gwen, et al. Chapter 8. Cultivating Constructive Metacognition: A New Taxonomy for Writing Studies. Critical Transitions: Writing and the Question of Transfer, edited by Chris M. Anson and Jessie L. Moore, The WAC Clearinghouse and UP of Colorado, 2016, pp. 217-49.

Hacker, Douglas J. Definitions and Empirical Foundations. Metacognition in Educational Theory and Practice, edited by Douglas J. Hacker et al., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998, pp. 1-23.

Horner, Bruce, et al. OPINION: Language Difference in Writing: Toward a Translingual Approach. College English, vol. 73, no. 3, Jan. 2011, pp. 303-21.

Jarratt, Susan C., et al. Pedagogical Memory: Writing, Mapping, Translating. WPA: Writing Program Administration, vol. 33, no. 1-2, Fall/Winter 2009, pp. 46-73.

Lorimer, Rebecca. Writing across Languages: Developing Rhetorical Attunement. Literacy as Translingual Practice: Between Classrooms and Communities, edited by Suresh Canagarajah, Routledge, 2013, pp. 162-69.

Lu, Min-Zhan, and Bruce Horner. Translingual Literacy, Language Difference, and Matters of Agency. College English, vol. 75, no. 6, July 2013, pp. 582-607.

Matsuda, Paul Kei. The Myth of Linguistic Homogeneity in U.S. College Composition. College English, vol. 68, no. 6, July 2006, pp. 637-51.

Moore, Jessie L., et al. Writing the Transition to College: A Summer College Writing Experience at Elon University. Composition Forum, vol. 27, Spring 2013, www.compositionforum.com/issue/27/elon.php.

Musgrove, Laurence. Attitudes Toward Writing. The Journal of the Assembly for Expanded Perspectives on Learning, vol. 4, no. 1, Jan. 1998, trace.tennessee.edu/jaepl/vol4/iss1/3.

Negretti, Raffaella. Metacognition in Student Academic Writing A Longitudinal Study of Metacognitive Awareness and Its Relation to Task Perception, Self-Regulation, and Evaluation of Performance. Written Communication, vol. 29, no. 2, Apr. 2012, pp. 142-79.

Negretti, Raffaella, and Maria Kuteeva. Fostering Metacognitive Genre Awareness in L2 Academic Reading and Writing: A Case Study of Pre-Service English Teachers. Journal of Second Language Writing, vol. 20, no. 2, June 2011, pp. 95-110.

Nowacek, Rebecca S. Agents of Integration: Understanding Transfer as a Rhetorical Act. 1st edition, Southern Illinois UP, 2011.

Pacello, James. Integrating Metacognition into a Developmental Reading and Writing Course to Promote Skill Transfer: An Examination of Student Perceptions and Experiences. Journal of College Reading and Learning, vol. 44, no. 2, Apr. 2014, pp. 119-40.

Reiff, Mary Jo, and Anis Bawarshi. Tracing Discursive Resources: How Students Use Prior Genre Knowledge to Negotiate New Writing Contexts in First-Year Composition. Written Communication, vol. 28, no. 3, July 2011, pp. 312-37.

Roseth, Bob. UW Fall 2013 Enrollment: Largest Freshman Class Ever | UW Today. 14 Oct. 2013, www.washington.edu/news/2013/10/14/uw-fall-2013-enrollment-largest-freshman-class-ever/.

Schraw, Gregory. Promoting General Metacognitive Awareness. Instructional Science, vol. 26, no. 1-2, Mar. 1998, pp. 113-25.

Scott, Brianna M., and Matthew Levy. Metacognition: Examining the Components of a Fuzzy Concept. Educational Research eJournal, vol. 2, no. 2, July 2013, pp. 120-31.

Sitko, Barbara M. Knowing How to Write: Metacognition and Writing Instruction. Metacognition in Educational Theory and Practice, edited by Douglas J. Hacker et al., Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, 1998, pp. 93-115.

Sommers, Nancy, and Laura Saltz. The Novice as Expert: Writing the Freshman Year. College Composition and Communication, vol. 56, no. 1, 2004, pp. 124-49.

VanKooten, Crystal. Identifying Components of Meta-Awareness about Composition: Toward a Theory and Methodology for Writing Studies. Composition Forum, vol. 33, Spring 2016, www.compositionforum.com/issue/33/meta-awareness.php.

Wardle, Elizabeth. Creative Repurposing for Expansive Learning: Considering ‘Problem-Exploring’ and ‘Answer-Getting’ Dispositions in Individuals and Fields. Composition Forum, vol. 26, Fall 2012, www.compositionforum.com/issue/26/creative-repurposing.php.

Webster, John. A Glossary of Common Learning Terms. Learning About Learning Common Terms and Concepts in the Field of Learning, n.d., faculty.washington.edu/cicero/learningresources2.htm#glossary.

---. Personal Interview. 29 May 2014.

Yancey, Kathleen, et al. Writing across Contexts: Transfer, Composition, and Sites of Writing. 1st ed., Utah State UP, 2014.

Zinchuk, Jennifer. Activating Learning: Teaching for Metacognition. Literacy & NCTE, 8 Feb. 2016, blogs.ncte.org/index.php/2016/02/activating-learning-practical-teaching-interventions-to-foster-student-metacognitive-patterns/.

Getting ‘Writing Ready’ at the University of Washington from Composition Forum 37 (Fall 2017)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/37/washington.php

© Copyright 2017 Jennifer Eidum Zinchuk.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 37 table of contents.