Composition Forum 45, Fall 2020

http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/

Audit of a Profession: The Virtues of (Very Belatedly) Meeting Ann E. Berthoff’s Challenge to Composition

In this retrospective, we merge with and reflect on Keith’s unpublished Audit of a Profession (late 1990s), a retrospective that considers the field’s resistance to the philosophy and methodology of one of its founders, Ann E. Berthoff. Ann’s voice shook composition scholarship in the 70’s and 80’s by demanding that the nature of the relationship between language and meaning is three-fold, not direct. Accounting for “the third” element requires writing teachers to make radical changes to what and how they teach. In the 1990’s, Keith found that, despite decades of Ann’s drumbeat calls for the field to account for the nature of language as three-fold in scholarship and practice, her work remained “unaccepted without rejection.” Offering a reintroduction to some of Ann’s key concepts, this retrospective suggests that contemporary writing studies could benefit now more than ever from studying Ann’s pedagogy of forming. Given the radical humanism at its core, Ann Berthoff’s call to teach the possibilities inherent in writing as “forming” could manifest the social justice consequences for writing classrooms so many of us have cried out for since Composition’s inception, consequences that seem as crucial now as ever. We retain the sense of dialog in Piage’s reading of Keith’s text by labeling some sections as “Paige” and others as “Keith.” Keith’s sections remain largely as written over two decades ago, since we find that little has changed in the discipline’s reading of and reaction to Ann’s work.

Ann Berthoff’s Legacy

Paige

At the end of my first foray into the Archives & Special Collections of the Joseph Healey Library, University of Massachusetts Boston, I felt exhausted. In part, the fatigue stemmed from trying to cram my experience of the newly processed collected papers of Ann E. Berthoff into two days. Widely considered one of the founders of the field of composition and rhetoric (hereto “Composition”), Berthoff served the English department at UMass/Boston for nearly twenty years. She’d begun as Lecturer and moved to Associate Professor even without a PhD. Eventually, after decades of authorship in Composition’s major journals, Berthoff insisted her way to full Professor. She’d also published prominently in fields such as semiotics, education, philosophy, and English literature. Berthoff’s books—perhaps especially The Making of Meaning and The Sense of Learning, Forming/Thinking/Writing: The Composing Imagination (her 1978 textbook), and The Mysterious Barricades: Language and its Limits—garnered acclaim across disciplines. Among compositionists though, Ann Berthoff is most recognized as the Berthoff of the 1970’s Berthoff/Lauer debates. She won the 4C’s Exemplar Award with Janice Lauer in 1997. Berthoff’s acceptance speech is in the archive. “I’m ... surprised to be here,” she writes, “—and I’ll begin by telling you why ...”

I’d lit on that speech day one. The next, my final day, had me speeding through folders, leafing around duplicate publications and bundles of postcards from former students. That’s when I found something else that made me pause. A printed-out email. At the top, in large, penned letters: “Ann- You have become an email subject—C.”{1}

The “C” is Cheryl Glenn, who had snail-mailed the printout to Berthoff, an admitted techno-skeptic. My interest in digital media studies and new materialisms had led me to Berthoff in the first place, though those familiar with her work might find that curious. When I first spoke with her, even Ann herself, now 96 years old, voiced doubt in response to the idea of bringing “Berthoff” to the teaching of writing in digital spaces. But I am a writing teacher with a quarter century of experience teaching first year writing, and as I’d come to understand Ann’s philosophy, her pedagogy of forming began to resonate not only with my teaching experience, but also with my studies in digital media and new materialisms. When I saw the email from Glenn in the archive, my interest piqued.

The email, posted to the wpa-listserv, 28 April 1997, is from Keith, then Coordinator of Composition at Northwest Missouri State University. In the email he wonders how many of us have read the entire works of other Composition scholars. He writes this: “... by the end of summer I’ll have finished reading all of Berthoff ... My reaction to this has been to wonder just why Berthoff’s theoretical thinking seems not to be as pervasive in our published theoretical work as one would think from the frequency with which she is included on relatively brief reading lists in relatively key places (e.g., graduate courses)”. Here I was, working on a dissertation published in 2019, twenty years after Keith’s email, essentially asking the same kinds of questions of Berthoff’s legacy: Where is Berthoff’s philosophy—materially, theoretically, practically—in our contemporary conversations? I’d read Berthoff’s name in introductions to contemporary monographs or sections of chapters (Hawk, Fleckenstein, Micciche, Sanchez), and occasionally her name makes the title of an article (Palmeri & Rutherford). But I’ve found virtually no instance of contemporary scholarship in which Berthoff’s ideas are discussed with focused attention in the full context of her philosophy.

Like Keith’s twenty years ago, my instinct tells me that Ann Berthoff’s philosophy matters. Crucially. And it matters not just to the few scholars who, in one way or another, have come to embrace Berthoff’s pedagogy of forming—her former students like Richard Miller, the many established scholars who remember Berthoff herself and respect her work, or her colleagues such as Hephzibah Roskelly, Kate Ronald and others of a generation at the brink of retirement. Berthoff’s philosophy speaks to the heart of Composition: what we do, who we are as a field, and who we could be as a discipline. My contemporary studies attest to the fact that Ann Berthoff’s work, as Keith noted back in 1997, continues to whisper through Composition, offering critique of and guidance for the field that is as potentially revolutionary as ever.

When I contacted Keith to ask him about his studies in Berthoffian praxis, he sent me a draft of an article he’d completed around that time (late 1990s) but never sent out for publication. The draft, tentatively titled Audit of a Profession: Meeting Berthoff's Challenge to Composition or Whispers in Class: Berthoff's Place in the Conversation of Composition, thinks through possible reasons why the field seems to avoid the radical implications of Berthoff’s philosophy, and it claims that writing studies continues to pay a steep price for doing so.

As I read Keith’s draft, I was struck by its timelessness.

Usually, change-over-time defines Retrospective contributions. Most submissions feature an established scholar looking back on long-ago publications and assessing the ideas formulated there in light of contemporary contexts and perspectives. In nearly all of them, authors report that, looking back, they now see “gaps in understanding” or opportunities for “more in-depth study” (Mutnick & Carter). They perceive “limitations” in their previous conceptions, or “omissions” (Micciche). Even essays such as Bawarshi and Reif’s retrospective on their 2002 interview with Susan Miller tend to see something different, something changed—new treasures in original works. In this essay, however, Keith and I marvel at the unchanged value of Berthoff’s philosophy; despite fifty years and three generations of Composition scholarship, Ann Berthoff’s pedagogy of forming has remained stubbornly, consequentially—and perhaps wonderfully—relevant and full of possibility.

This retrospective puts into dialogue Keith’s unpublished Audit of a Profession and my contemporary understanding of the pedagogy of forming, as sustained by conversations with Ann Berthoff herself. With this work, Keith and I hope to inspire two avenues of inquiry:

-

Renewed attention to Berthoff’s complete philosophy. We suggest that the relevance and implications of Berthoff’s praxis—literacy instruction rooted in Peircean triadic semiosis—remains as pertinent as ever in the digital age, and remains, too, woefully under-considered by the field.

-

And deep contemplation of “the problem of Ann Berthoff”: what keeps her philosophy “unaccepted without rejection”? And what does that suggest about the culture of Composition then and now?

This is much work for just a few pages, especially when Berthoff’s praxis challenges perhaps the most fundamental relationship defining what we do (or could do) as compositionists: the relationship between writing and meaning. Not only that, but despite contemporary references to her ideas, Berthoff’s philosophy as a whole seems to be fading from our collective understanding.

So, this retrospective serves as a gloss, a finger pointing to a very large, mostly hidden, door: Ann Berthoff’s philosophy. There are consequences for ignoring it, we argue. Holding Berthoff’s work in limbo, “unaccepted without rejection,” keeps writing studies from coalescing around one of its most vital, humanist responsibilities: to teach people how to use writing as a way of making meaning—of becoming the problem posers, not just the problem solvers.

Keith

Ann Berthoff's glittering intelligence runs through the conversation of composition and rhetoric, preserved in her memorable terms. When we speak of killer dichotomies, of double-entry journals, of recipe-swapping, of pedagogies of exhortation, of meeting students where they are, of writing as the ordering of chaos, of revising as Re-Vising, or of “allatonceness,” we use language that Berthoff either invented or made suddenly more powerful. Indeed, when we refer to larger matters like semiotics, hermeneutics, or Paulo Freire's concept of conscientization, we continue important, if conceptually difficult, conversations diverted into our own in significant part by Berthoff. Her textbook, Forming/Thinking/Writing, converted theory into practice thoroughly and deeply. It was admired for its method and philosophical acumen by critical theorist Paulo Freire, certainly not a reader to whom most of our composition textbooks would have appealed (Freire, Foreword). Her textbook goes beyond the more normal scholarship of simply criticizing traditional pedagogies, applying critical understanding to the creation of whole new ways of teaching writing. Her landmark book The Making of Meaning completely broke the existing molds, departing at once from what was then the largely historical scholarship in rhetoric and the largely form-driven scholarship in composition, moving past even the nascent process movement, fully theorizing writing instruction in its entire context. Her challenging essays throughout the 1980's, the strongest of which were eventually collected in The Sense of Learning, consistently presented writing teaching as at once philosophical, psychological, and social.

Berthoff’s Ideas: The Pedagogy of Forming

Paige

Berthoff was able to do this—treat the teaching of writing as all-at-once social, psychological, and philosophical—by thinking with the concept of “form.” Although Berthoff never named her approach to the teaching of writing, we’re calling it “the pedagogy of forming,” and it rises from her deep understanding of C.S. Peirce’s triadic semiosis. The following terms comprise a few of the key concepts rooting Berthoff’s philosophy and her pedagogy of forming:

Triadic Semiosis

Triadic semiosis, or “triadicity,” is the theory that all meaning is mediated by meaning; there can be no direct relationship between a sign and the thing-in-the-world to which it refers, and yet there always remains a real, mediated coherence. It’s a simple idea, really, and one that confirms quotidian experience. But the implications of triadicity reach far and challenge the core commonplace notions about the teaching of literacy.

For instance, consider the associations your mind makes in response to Figure 1:

Figure 1. What do you think when you look at this?

Perhaps words come to mind: “blob,”

“amoeba,” “liver,” “sinking tugboat,” “gestalten,”

“form,” “udi.” Maybe the image evokes memories. Sensations.

Emotions. Sounds. Or other images—perhaps, 形状.

Whatever associations happen when you experience the given form, the

material for those associations exists in you to begin with. From a

triadic perspective, that’s what meaning is: the evocation that

happens inside a person encountering the world—including texts,

“signs” like “A” or “cattle,” 49 or ♿

. These signs—and the meanings they gather for you—become

meaning-material evoked in future associations. “Signs” are

forms.

. These signs—and the meanings they gather for you—become

meaning-material evoked in future associations. “Signs” are

forms.

Form

A form is anything with limits, boundaries, borders; all forms are Something and Not-something-else. But—and here’s the essence of triadicity, what distinguishes it from other theories of meaning, being, and signification—forms are always forming. Triadic pedagogy accounts for, centers, and capitalizes upon this mutability.

In a sense, of course, we are forms, delimited physically and immaterially, by skin, physiology, ideas, thoughts, feelings, memories. We are meaning-full beings, with agency—the ability to engage our imaginations to generate choices, and to choose.

Pragmatism

Thus we, in our contexts, are all also full of potential. From a triadic point of view, there is never one, specific, “objective,” deemed-by-nature, “right” association to be made in regard to a “sign,” a form. There is just “what is,” which is slightly different for everyone, and “what could be” (what Peirce deems “pragmatism”). Whatever associations one person experiences in response to a sign is just as “right” as the next person’s. But this isn’t to say meanings, and the realities they construct for us, are completely relative or random, or so idiosyncratic as to make mutual understanding and communication (and teaching) impossible—as experience confirms. The meaning-making process produces commonplaces, “norms,” that we collectively treat as if “true”; but Berthoffian triadicity understands, and accounts for, the malleability of these norms. That’s what’s so hopeful about Berthoff’s philosophy, and what makes the pedagogy of forming a kind of critical pedagogy. The pragmatic practice of questioning (problematizing) language practices that most people take for granted—like gender pronouns, say—opens possibilities for new meanings: they/them, xe/xem, or ... ? What happens if we put it this way, or that? What ideas do these new meanings gather? For whom? In what contexts? What new meanings could people create through them? To what effect emotionally, materially? Note the naturally rhetorical nature of this thinking. From my Berthoffian-inspired view, rhetoric has become this: accounting for the contextual dimensions of meaning. It is apprehending the limits that define relationships and acting consciously within and upon those limits. Fundamentally, rhetoric is operating from the knowledge that things could mean—and thus be—otherwise.

Dialectic

Triadicity posits that norms and forms are fields of potential, always shifting and changing, but not “indeterminable” (Berthoff, The Mysterious Barricades). When viewing the image in figure 1, for instance, there are associations we’ll wager that you did not make. You did not think “rainbow” in response to the image. You did not suddenly imagine birds singing or remember the time you accidentally drove your Big Wheel into the pool behind your uncle’s house. And this is true no matter where you come from or what language you speak, the genders you occupy, the ethnicities and cultures with which you identify, your age or your economic situation, or the state of your body at any particular time.

These fields of potential, and the actualities that manifest from them, form as a result of the back and forth between elements in environments: dialectic. This back and forth happens inside of us—our emotions and sensations resonating with memories meeting new information. Simultaneously, “allatonce,” this oscillation occurs between individuals and their social environments. The socio-historical is constituent of all emotion, sensation, and experience. The pedagogy of forming simply enrolls writing in the service of generating an awareness and understanding of this natural system of dynamic reciprocity that constitutes meaning.

Allatonceness

From a triadic perspective, to be human is to be a flesh and blood vessel shaped by past experience (physical and immaterial) into potential and realized translations of current and future encounters with new experiences and ideas, and the inevitable texts constituting those new experiences and ideas. This is a system of meaning, always in motion. There is no fixed right or wrong, correctness and error, in this perspective; there is only human nature manifesting awareness, choice-making, and effect.

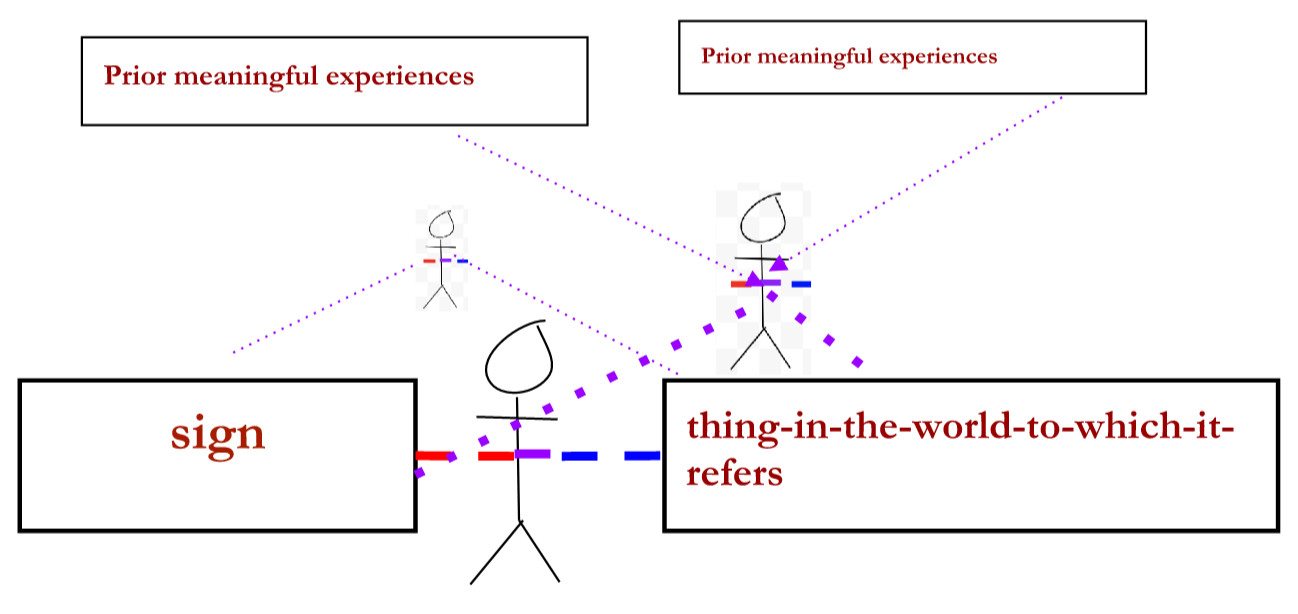

Figure 2. Tracing triadicity. The purple dashes represent the place where human meaning happens, inside each person

In Figure 2 above the purple dashes represent the meaningful connection made between a sign and the thing-in-the-world to which it refers. That dash only manifests inside of a person (not necessarily only human animals), and the purple dash of meaning is constituent of previous experiences, thoughts, and feelings. One of the implications of a triadic understanding of the relationship between meaning and signification is that all signs are wholly or in part artifacts of previous moments and [human] sites of meaning-making. The sign “is/becomes” by virtue of a simultaneous (all-at-once) interaction of past and present, social and personal, textual and non-textual, in-form-ationings; a sign is an artifact with contextual legacy, and a person’s re-cognition of that sign (connecting sign and the thing-in-the-world-to-which-it-refers) simultaneously perpetuates and evolves the meaning potential of that sign as it manifests within communities.

Meaning doesn’t happen, then, as a step-by-step process. It is neither purely personal nor social in its essence. Past, present, and future-as-potential—individual and community—exist simultaneously in meaning-making. Berthoff calls it “allatonceness” (see especially Allatonceness in The Sense of Learning) and part of her campaign against pedagogical practices that break writing down systematically—such as into correctness and error, or into steps and categories—emerges from her ability to appreciate the richness of interaction and interpretation at the heart of meaning-making to begin with. Berthoff always accounts for “the third,” meaning as mediator, and accounting for “the third” marks the pedagogy of forming.

And here we find a consequence of Berthoff’s philosophy that matters as much today as ever: from a Berthoffian perspective, the shift to valuing “process over product” that often defines the process movement in Composition history has been no shift at all. Writing instruction has simply gone from defining and expecting “correct” and aesthetically pleasing (to those in power) final texts, to defining and expecting “correct” or formulaic processes for producing final texts. In both situations, students are taught content that is defined, delivered or provided, and assessed by those in privileged power positions. The difference of what “side” of composing you’re focusing on—process or product—makes no difference at all from a Berthoffian point of view; the power dynamics within the classroom and society remain the same, top-down, those in power feeding “knowledge” (of Standard American White English, of writing, of oppression) to the oppressed/suppressed.

Berthoff’s philosophy offers a genuine escape from the unhelpful process/product dichotomy. A pedagogy of forming engages students in using writing to generate awareness of writing as meaning-making. There are no formulas to learn, no particular categories or steps to practice, no patterns to memorize that define, say, an introduction, or an essay. A pedagogy of forming does not teach specific forms directly; rather, it guides students into the awareness that they form meaning already, naturally, and that writing is a way of forming, a way of making meaning. A pedagogy of forming guides students into the awareness that oppression is a language construct—meanings made, that could be made differently to yield different power relationships.

Berthoff’s pedagogy of forming—her specific notions of triadicity, form, pragmatism, allatonceness, and dialectic—uniquely accounts for the omnipresent fact of human interpretation and the dynamic nature of meaning (in any environment and medium). And for many of us who have been fortunate to experience what it’s like to teach a course anchored in the pedagogy of forming, even if we’ve been teaching for decades, we know the feeling of what it’s like to teach writing for the first time. Writing—not Standard American White English or specific texts or anthropology, or cultural studies, or philosophy, or media studies, or communities. Writing as thinking, as making meaning.

The Hold Up

But wait.... If Berthoff’s ideas were so great back in the late twentieth century, and they were never pointedly challenged or rejected by scholars in the field, why did those ideas fail to take hold in Composition? This was the central concern of Keith’s Audit of a Profession. It also became one of the central questions of my 2019 dissertation, Ann Berthoff from the Margins. If I could figure out why the field has seemingly marginalized Berthoff’s philosophy, I thought, perhaps I could reintroduce her ideas in a way that avoids the same fate. Keith’s conclusions in Audit did not leave me feeling hopeful. But they did resonate with my experience as a researcher engaged in the study of Ann Berthoff’s life and work. Here are those conclusions:

“Too Much Too Soon: Berthoff's Maturity in a Boomer Field”

In this section, Keith identifies Ann’s philosophy as “before her time.” It’s a designation that she refutes. I think her resistance to the designation stems from her focus on our tendency as humans to form meanings naturally, constantly; this tendency is never out of date. Some scholars, such as Paulo Freire, deem this aspect of our nature what makes us human in the first place. As I took in Keith’s essay, I wondered this: if Berthoff’s uncontested philosophy is rooted in an aspect of human nature, what does it say about Composition that the field has yet to arrive at a “time” for Berthoff?

Keith

Berthoff's first published article in this field was (fittingly, given her championing of dialectic) a response to another article. In 1971, in her mid-forties—an age by which rhet/comp's fiercest young lions start to think in terms of having published their age in articles—Berthoff officially crossed over from literary criticism to composition and rhetoric. It is useful to look back at College Composition and Communication from those days to realize how much more informal and even simplistic the journal was in 1971, a year by which the most precocious of comp/rhet's Boomers might have been typing up their dissertations (overwhelmingly on literary subjects, of course). This was a time when most other composition pioneers of note were still finding the issues on which they would lay the groundwork for the Boomer boom in rhetoric and composition theories. The article to which Berthoff responded, by Sister Janice Lauer (1970), was simply a brief proposal, accompanied by a much longer bibliography, urging compositionists to take more interest in cognitive psychology.

Looking back at it from our perspective and in isolation, Berthoff's response (The Problem) seems entirely unremarkable; but in that lies its very claim to warrant remark. Rigorously backed by a solid, fully articulated philosophical perspective, Berthoff's response was almost a new thing under the sun: a discussion of composition practice as the subject of intellectual theorizing of the highest order. That it could be published today, needing only current levels of attention to bibliography and citation, is immediately evident; and a review of the remainder of that issue brings about the more measured realization that in meeting current standards Berthoff's work was extraordinary for its time. Sister Lauer can hardly be faulted for her somewhat vacillating rejoinder (1972); the very possibility of a response such as Berthoff's would have been very difficult to anticipate.

Berthoff's surrebuttal, published in College English (From Problem-Solving), set out even more completely the fundamental premises of her theories, a statement from which she has never had cause to vary significantly. Those theories themselves will unfold more fully in the next sections of this argument, though on the whole the point of this article is not to re-iterate what Berthoff herself has written so well over so many years. What is more interesting here is that at a time well before most of composition and rhetoric's professionalizing Boomers were active in the field, Berthoff was pretty much already saying what she has ever since—and encountering as little meritorious rebuttal or apparent understanding as we have since been able to muster.

As a result, one hypothesis for the odd “non-acceptance without rejection” status of Berthoff's work may have to do with its unfortunate timing in the fashion cycles of the discipline. In 1971-72, Berthoff was much too far ahead of her time; but by 1981, and then 1987-88, and then 1993 (to cite other high-water marks in her publication career), her ideas were old news, from an old woman. I hate to think that her lack of a traditional full-time academic post have contributed to her reception, but an hypothesis based in part on fashion sense cannot exclude the possible effects of such things. Mainly, though, she just seems to have become old hat before we ever completely caught on to what she was saying. While her later publications outside of composition have won awards (Walker Percy's Castaway) and prestigious placement (Sapir and the Two Tasks of Language), in composition she has been treated more as an object of nostalgia, with “emeritus” special placements in leading journals (e.g., Rhetoric as Hermeneutic) and even, many years ago now, a festschrift on her behalf (Smith). With a more recent article in College English (Problem-Dissolving) and her CCCC Exemplar's address, perhaps Berthoff was declaring that the rumors of her fossilization had been greatly exaggerated; but again an almost eerie silence ensued in response to her typically bracing challenges to current orthodoxy. In the most tragically hip field in academe, perhaps the main thing the Boomers ever did anywhere that really lasted or meant anything, Berthoff simply does not fit in. Too old to be hip, too lively to be an honorific elder sage, she has been the equivalent of a sixties suburban mom in a seventies new wave band; and it is perhaps all to the worse that her chops have always been sharp.

“The Personal Is the Professional: Berthoff's “Rambo” Attacks on a Fragile Field”

Paige

Ann Berthoff suffered no fools in writing. If your ideas were, in her view, wrong ones, Ann would tell you so. This endeared her to many, including me. But her personality cultivated genuine disdain between herself and other scholars, perhaps the most notable being Ross Winterowd.{2} Sometimes that disdain flowed one way. She couldn’t tolerate James Berlin’s ideas, for instance, and held him especially responsible for installing trap terms that, from a Berthoffian view, continue to obscure the possibilities inherent in triadicity. But Ann could disagree on fundamental levels with colleagues and still respect them, as it was with James Moffett, for instance, who was, in Ann’s words, “the absolute opposite of anything I ever tried to do” (Arrington 217).

Keith

Perhaps Berthoff’s work has suffered greatly from personal reactions to Berthoff's critical personality. In her years of deepest engagement with the field, the years between 1971 and 1993, Berthoff's writings were marked by a form of inquiry that was often agonistic, even antagonistic. Berthoff responded to specific articles, named names, swapped insults, and called it as she saw it. To use the current vernacular, she often flamed people, and she expected to be flamed in return.

Composition scholarship regularly features indirect personal attack, of course, and direct attack upon the objectified merit of an author's writing and thinking. We are even able, often, to spy the cunning knife beneath the cloak. Rarely, though, do we encounter in our journals the willingness to, for an archetypal Berthoffian example, call our opponent a “diligent reader of prefaces ... [who] in this instance has actually reached page 46” (A Comment on ‘The Purification’). A community of discourse founded by people who tend to be unusually sensitive to such critique certainly may not take easily to Berthoff’s aggressive style.

Berthoff’s use of that style, however, was hard to separate from her incisive thinking. We can see it doing considerable work in that initial exchange with Sister Lauer:

If studying “the problem of composition” leads us to consider the use of metaphor, the logic of analogy, the various means by which we come to know our knowledge and hence ourselves, then it can be enormously beneficial ... . Instead, the [Dartmouth] Conference concluded that “English” is somehow involved with “intellectual” uses of language, and that what we teach is “communication” and “expression.” “The intellectual uses of language” were identified with problem-solving and then posited as the polar opposite of “creativity.” This spurious opposition (it is not a logical antithesis) of the “creative” and the “intellectual” has been the primary contribution of the psychologists of learning to the field of the teaching of English. The harm it has caused is scarcely calculable.” (“The Problem” 238)

Those scare quotes may seem at first merely snarky, but it vividly illustrates how careless uses of words can build a false dichotomy and an apparently reasonable argument that, aggressively unpacked, comes to seem quite shoddy.

Berthoff herself acknowledged, only somewhat in jest, her “Rambo temperament” (How Philosophy 83). Despite the consistency of this form of “Rambo” inquiry with her theories of rigorous dialectic, many in the field may have seen it as unacceptable pugnacity. Most likely, there were kinder, smoother, ways to make these cases. Perhaps we should hold Berthoff's “Rambo” approach against her. Despite its consistency with her theories, her dialectic could certainly have been handled with more diplomacy. Her attacking style could even be read to indicate ideologies working through her that could be productively questioned. Yet Berthoff’s in-your-face personality is an unavoidable part of nearly all of her work, not just the most memorable of her attacks. In essence, Berthoff blithely tramples a boundary of depersonalized, sophisticated discourse. Further, after reading a steady diet of Berthoff, it can come to seem odd how homogeneous the personal style of other composition theorists really is, how carefully so many of them walk the same fine line between the Scylla of personal engagement and the Charybdis of scientistic detachment. Berthoff simply does not adhere to those discourse community conventions. It is as if someone should bite off the end of a fine Cuban cigar before lighting it!

“Toward a More Berthoffian Profession?”

Paige

In my experience, one of the challenges of advocating a Berthoffian position manifests around this issue of tone. Throughout my dissertation process, I was kindly advised on multiple occasions by well-established scholars in the field (whom I admire, respect, and like, immensely) to reconsider my tone. Because no one wants to hear directly that what they’ve been doing is wrong or mistaken, or that what they are doing isn’t helping. Maybe focus on the possibilities, they advise. How could Ann’s philosophy enrich our existing practices?

And yet, as perhaps we rhetoricians know especially, there exists, like a coin, a space where tone and substance meet, where changing the tone changes the meaning. In my experience, accounting for “the third” tends to challenge the most fundamental valuation of most ideas about the teaching of writing. Keith’s final observation in Audit identifies how, despite Composition’s continued referencing of terms, concepts, and phrases extracted from her philosophy, the substance of Ann Berthoff’s challenges to the field—the view of Composition constituent of Ann’s directness—no longer garners much response and is in danger of fading away entirely.

Keith

There is, of course, one more explanation of Berthoff’s universal but shallow praise in contemporary Composition studies. Perhaps her ideas have been examined thoroughly and have been found wanting. If so this has been a curiously quiet affair, however. After all, the record of direct opposition to her central points themselves—that is, to her substance, not her style—has been extraordinarily thin. Further, to a very large extent such citations to her work as there are tend to approve of it, or even seek to verify new declarations by indicating that they are coherent with Berthoff’s ideas. Rather, it is highly likely that the record must be taken on its face: Berthoff’s actual program has simply been under-explored and poorly understood.

To realize fully the import of Berthoff’s vision of Composition, it is useful to remind ourselves of the obvious facts about Composition’s present state of limitation as a professional discipline. First, little of Composition’s professional activity has had any visible impact on vast swaths of writing classes. A great many college writing students are taught by underprepared, underpaid, undersupported teachers, whether of the adjunct, temporary, or apprentice variety. Many other students are taught by English professors with other specialties. And much fully professional work in Composition has been both focused upon and dissipated by the challenging craft of writing program administration. Despite the great premium supposedly put on writing by academe and business, students must be forced to enroll in composition courses. And multiple strong economic forces work to get them through such classes as soon as they might be minimally competent in whatever the classes have to offer. Meanwhile, careful examination of syllabi reveals to anyone who has done it that most teachers apparently believe putting real energy and substance into composition classes almost always depends on including other kinds of material (from literature to cultural studies) or activities (from technology to service learning)—or even Composition’s very own unkillable zombie, grammar study.

Bluntly put, there is little evident justification at present for anything like a “profession” focused on composing itself, seen with the focus with which Berthoff has always asked us to see it.

Berthoff Now, Still, More than Ever

Paige

No mere curiosity compels us here to reintroduce Ann Berthoff, her legacy, and her pedagogy of forming. We have defined key concepts central to her theory of language, Peircean triadic semiosis, so that new scholarship might take up Ann’s philosophy, not just her terminology. But as goes the nature of terms, Berthoff’s terms—triadicity, form, pragmatism, dialectic, and allatonceness—lose their meaning and their power when divorced from her philosophy. If more scholars might return to Ann’s philosophy, they might begin to “think with” Berthoffian concepts in dialogue with other ideas in Composition and new ones could be born.

Do we need new ideas? Perhaps one of the things we’ve learned from the dawn of the digital age is that there is no inherent value in newness. Social and economic inequities persist, in our writing programs and in the communities they serve. Could we change our practices in order to address those inequities in new ways? Berthoff’s work suggests that accounting for the mediating nature of meaning in our scholarship and practices, “the third,” could be the kind of change to help us address on a disciplinary level the kinds of inequities illuminated by our scholarship time and again. And although her ideas are not “new,” they are different, and they yield different kinds of practices.

I have just recently begun to practice the pedagogy of forming in my own first year writing classes. Last year, each course culminated in an essay (or other textual form of choice) that “thinks with” the meanings outlined in a general rubric about the student writing conducted throughout the semester (not just in our course). Each student’s final, comprehensive reflection we prepared for by dialoguing about the work from the beginning. The art of “thinking with” has become one of the methods I try to encourage students to grow aware of so that they can practice assessing their own work and engage with expectations consciously, far beyond first-year writing.

Yes, the terms with which I describe the course above are Berthoffian terms, but more importantly, they are deployed in the spirit of Berthoff’s philosophy. This is reflected in the course outcomes I revise along Berthoffian lines. For instance, “Engage in writing as a process, including various invention heuristics (brainstorming, for example), gathering evidence, considering audience, drafting, revising, editing, and proofreading” becomes this: “Engage consciously in writing as a way of making meaning, of generating choices, considering relationships, and observing forms.” The language of the former outcome evokes a sense of chronological steps: first we brainstorm, then we gather evidence, then we consider audience, then we draft, revise, edit, proofread. The latter avoids creating that false sense of sequence. One might ask, what does “consciously” mean? And my students do ask that. And so we dialogue about it—What could it mean?—defining as we go, making the meaning, together. “This class feels like a philosophy class,” they tell me. “Only one I can understand.” And that’s when I know I’ve got it.

Perhaps the most challenging aspect has

been bringing students into the world of responsibility when it comes

to writing. No, a paragraph is not 5-6 sentences long. But it can be.

Yes, a paragraph can be one sentence long. What

is a paragraph? How

could we define “paragraph”? Don’t freak out, but there’s not

“a” way. There are many ways. A “way” is a method. For twelve

years, our students have been given methods, methods that don’t

work well for them beyond taking specific tests. Triadic pedagogy

aims to prepare students for forming their own methods of thinking

and writing, of thinking through writing. Methods of composing.

Conclusions

Berthoff’s philosophy might be “old news from an old woman.” But if Keith and I are correct, and Berthoff’s ideas simply remain unaccepted without rejection, then great opportunities exist in considering Berthoff’s implications for Composition scholarship and practice. In the spirit of Keith’s 1990s “Audit of a Profession,” we might wonder what the field’s response to Berthoff’s work says about the culture of Composition broadly, so that new scholarship might take up the call to contemplate the constructiveness of such a culture. And in the spirit of Paige’s contemporary studies of the pedagogy of forming, we might wonder how the pedagogy of forming might help us address contemporary issues in writing classrooms and programs. Berthoff’s philosophy transcends media (we like to think Paige has convinced her of that, too), transcends languages and dialects, grammars and genre, communities and identities. All of our rhetorics are first acts of composing.

Keith and I engage in this work because we understand that perhaps the most consequential implication of Ann Berthoff’s philosophy is the clearly defined space that philosophy makes for Composition as a “profession” or, in our contemporary conversations, as a “discipline.” From the beginning Ann taught us that writing—and reading, and teaching, and learning, and making—are all acts of the composing imagination. So, if we teach students, first, how to harness the power of the composing imagination, then everything else we teach—grammar, poetry, business writing, cultural rhetorics, multimodality, accessibility, digital media ... everything, including learning—can fall more under the control of composers. Not only do they become people equipped to solve problems; they become empowered to use their own meanings, in dialogue with the meanings that constitute their world, to define those problems in the first place. In essence, that is the gift of the pedagogy of forming, the way it gives back to students of all varieties and identities the power of the composing imagination.

Notes

-

Glen, Cheryl. Note to Berthoff, 29 April 1997. Box 5, Folder 1, Various Writings and Collected Articles 1975-2000, The Ann E. Berthoff Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Joseph Healey Library, University of Massachusetts, Boston. (Return to text.)

-

Several instances of Berthoff’s unadulterated views of Ross Winterowd are instantiated in her papers. For example see: Berthoff, Ann. Letter to Friends and Colleagues, 05 March 1993. Box 5, Folder 1. Various Writings and Collected Articles 1975-2000, The Ann E. Berthoff Papers, Special Collections and Archives, Joseph Healey Library, University of Massachusetts, Boston. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Arrington, Paige Davis. Ann Berthoff from the Margins: An Infusion of All-at-Once-Ness for Contemporary Writing Pedagogy. ScholarWorks @ Georgia State University, 2019.

Bawarshi, Anis, and Mary Jo Reiff. Composition and the Cultural Imaginary: A Conversation with Susan Miller. Composition Forum, vol. 13, no. 1/2, Jan. 2002, pp. 1-22.

Berthoff, Ann E. A Comment on 'The Purification of Literature and Rhetoric.' College English, vol. 50, no. 1, 1988, pp. 95-96.

---. Forming, Thinking, Writing: The Composing Imagination. Boynton/Cook, 1978.

---. From Problem-solving to a Theory of Imagination. College English, vol. 33, no. 6, 1972, pp. 636-49.

---. How Philosophy Can Help Us. Pre/Text vol. 9, no. 1-2 1988, pp. 61-90. A Polylog with John Schilb, Patricia Harkin, and C. Jan Swearingen.

---. The Making of Meaning. Boynton/Cook, 1981.

---. The Mysterious Barricades: Language and its Limits. University of Toronto Press, 2016.

---. The Problem of Problem Solving. College Composition and Communication vol. 22, no. 3, 1971, pp. 237-42.

---. Problem-Dissolving by Triadic Means. College English vol. 58, no.1, 1996, pp. 9-21.

---. Remarks on Acknowledging 1997 Exemplar Award, CCCC, Chicago, April 1998, Box 5, Folder 39, Series IV, various writings and collected articles, The Ann E. Berthoff Papers. Special Collections & Archives, Joseph Healey Library, University of Massachusetts, Boston.

---. Rhetoric as Hermeneutic. College Composition and Communication vol. 42, no. 3, 1991, pp. 279-87.

---. Sapir and the Two Tasks of Language. Semiotica vol. 71, no. 1/2, 1988, pp. 1-47.

---. The Sense of Learning. Boynton/Cook, 1990.

---. Walker Percy's Castaways. Sewanee Review, vol. 102, no. 3, 1994, pp. 409- 23.

---. What Works? How Do We Know? Journal of Basic Writing, vol. 12, no. 2, 1993, pp. 3-17.

Fleckenstein, Kristie S. Embodied Literacies: Imageword and a Poetics of Teaching. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2003.

Freire, Paulo. Foreword. Smith xi-xii.

Hawk, Byron. A Counter-history of Composition: Toward Methodologies of Complexity. University of Pittsburgh Press, 2007.

Lauer, Janice. Heuristics and Composition. College Composition and Communication, vol. 21, no. 5, 1970, pp. 396-404.

---. Response to Ann E. Berthoff, ‘The Problem of Problem Solving.’ College Composition and Communication, vol. 23, no. 2, 1972, pp. 208-10.

Micciche, Laura R. Acknowledging Writing Partners. The WAC Clearinghouse, University Press of Colorado, 2017.

---. Staying with Emotion. Composition Forum, vol. 34, Summer 2016. Accessed 28 September 2020. http://compositionforum.com/issue/34/micciche-retrospective.php.

Mutnick, Deborah, and Shannon Carter. Valuing the Literate Skills and Knowledge of Academic Outsiders: A Retrospective on Two Basic Writing Case Studies. Composition Forum, vol. 32, Fall 2015. http://compositionforum.com/issue/32/mutnick-carter-retrospective.php.

Rutherford, Kevin, and Jason Palmeri. Toward an Object-Oriented History of Composition. Rhetoric, Through Everyday Things (2016): 96.

Sanchez, Raul. Function of Theory in Composition Studies, The. SUNY Press, 2012.

Audit of a Profession from Composition Forum 45 (Fall 2020)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/berthoff-rhodes-retrospective.php

© Copyright 2020 Paige Davis Arrington and Keith Rhodes.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 45 table of contents.