Composition Forum 49, Summer 2022

http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/

“My Job is Killing Me:” Discourse-Based Interviews Reframed for Linguistic Discursive Research

Abstract: This paper discusses the relevance of the discourse-based interview (DBI) for holistic research and access to more layers of meaning in the study of complex phenomena. We draw on our own work in workplace discourse and relevant research from different linguistic traditions, particularly sociolinguistic inquiry. We reflect on the potential of DBI for enhancing reflexivity and enabling the researcher and participant to co-create the research problem. We reposition ‘the interview’ from a tool for collecting self-reported data to a process of negotiation which allows for multiple and alternative readings of the researcher’s findings. We close the paper with a model and set of principles that expend the current framing of DBI and we provide directions for future research.

Introduction

The increase in qualitative approaches in social sciences, alongside the acknowledgment of the complexity of the lived experience, has led to the development of tools that aim to enhance the potential of established research methods to access participants’ knowledge and perception of reality. The research interview in particular holds a prominent position in the social science theoretical and analytical inventory and is the flagship tool in relation to the researcher/participant relationship. In linguistic discursive analysis, which is our disciplinary field, tools such as playback techniques, stimulated recall and discourse-based interviews are by now established. They constitute interview designs that aim at eliciting lay users’ interpretations of encounters and, simultaneously, seek to open and democratize the research agenda, moving away from the “researcher-agenda controller” ideal. However, despite the vast scholarship in the area, there is less systematic discussion on the role of the researcher in the co-construction of the event and the use of those tools. The focus typically remains on the capabilities of the tool and the participants instead of the dialogic process through which the researcher and the researched actively negotiate their accounts in the research context and frame the representation of results (Gubrium and Holstein 34; Pitman 286).

In this article we critically discuss this dialectic process of lay users’/researchers’ co-creation of reality in the research interview context. We look into the research interview as a context and event where the two interactants negotiate self/other understandings of a phenomenon in enacting their roles. We pay special attention to the discourse-based interview (DBI). We define DBI as a research approach aiming to enhance reflexivity and allowing access to more layers of meaning encompassing methods that enable research participants to provide accounts for aspects of their practice. The DBI is particularly appropriate for providing tools as well as a framework for capturing the lived experience of a phenomenon and the process of meta-reflection on it (Angouri, Culture 85). The relationship between experience and theorizing is central in all research and particularly in research that falls under the qualitative end of the research paradigms spectrum. Discourse-based interviews (DBIs) can offer a conceptual framework and methodological tool for complex research designs by: (a) bringing together methods that draw on quantifying patterns and using descriptive statistics alongside a commitment to exploratory methods which seek to capture the participants’ lived experience; and (b) by allowing for a multilayered analysis of interviews beyond traditional coding processes. We discuss those positions further and illustrate in the light of the data.

We align with the critique of the qualitative-quantitative (QUAN/QUAL) binary as oversimplifying or overgeneralizing the methods most research projects draw upon to address complex problems as well as the nuances in the ontological positions of researchers. While this is a case well argued in literature, the paradigm wars of the 80s (e.g., Bryman 79) are still echoed in QUAN/QUAL epistemological dispositions towards objectivity and subjectivity associated with (post)positivism and constructivism respectively (we take those to be well-known to the readership of the journal). The more recent trend towards mixed (MIX) methods aims to balance the contrast between paradigms and schools of thought. There is no doubt by now that the MIX paradigm, and pragmatist approach, has added a lot to social science research. However, the essence of the QUAN/QUAL contrast is still present and comes in guises under the MIX paradigm that often reinforce linearity and the essence of the divide. Research interviews as an almost prototypical tool associated with qualitative research are often good examples of the persistence of the binary. Supposedly qualitative interviews are commonly approached from the angle of accuracy, faithfulness and generalizability (Angouri, Quantitative 35) and the data are coded on the basis of word frequencies. This imposes a quantitatively-conceived qualitative guise which is deeply embedded in research scholarship. We argue that DBIs can provide a useful tool towards multilevel analysis and make a wide contribution to research thinking. We draw on interactional sociolinguistic tools to analyze the discursive work of the participants in negotiating their roles in situ, drawing on the expectations of role performance from their wider sociocultural context. We discuss this further in the light of our work and show the process by which a nuanced approach to coding and analysis can provide more depth in the interpretive potential of the researcher.

We start by discussing the role of the reflexive researcher and the interview as process and product and turn to negotiating first/second order accounts. We then provide an overview of the different types of research interviews and zoom in on the DBI. We connect with other studies that have adopted DBIs (e. g. Harwood, (In)appropriate 430, Interview-Based 500; Lancaster 120) and discuss an example from our data on formality in workplace emails (Machili, Writing 144-146) to illustrate our arguments. We close the article with directions for future research.

Negotiating Worldviews in the Interview Context—the Implications of Being Reflexive

The complex relationship between experiencing the world and translating and reflecting on it for research purposes is well captured in research methodology literature. Research interviews in particular have a long footprint in social science scholarship on their complexity, potential and value (see e.g., Strang 498) for addressing multiple layers of a phenomenon. To this day, they are employed in both (post)positivist and constructionist designs, where participants are either the source (of information, knowledge, the truth) or active agents in co-creating accounts with the researcher (Gubrium and Holstein 32). Our work is aligned with the constructionist end of the spectrum. We acknowledge, however, that it is not rare for constructivist approaches to translate participants’ accounts as products of the process without more than a brief or descriptive reference to the researcher’s role in elicitation. Although framed often as two ends of a spectrum, (post)positivist and constructionist designs often result in reading data in surprisingly similar ways.

Our interest here is the potential of DBIs for capturing the interactional work of the researcher/participant dyad and, in the process, the multiple angles of a phenomenon. The DBI interview itself can be a target for analysis which can usefully shed light on the multiple roles the interactants take. We draw on interactional sociolinguistic theory and method which gives insight into how the process is negotiated in situ. We understand the interview as a context and event which comes with specific expectations of form and function. If we live in the interview society (Atkinson and Silverman 304; Silverman 144) then both the researcher and the participants have concrete expectations of the interview, what it looks and sounds like and what is its purpose. In this context, the interactants adopt their situated roles of interviewer-participant, but as the interaction unfolds, they alternate them with social roles (when they do bonding and collegiality, for example) as well as their roles that pre-exist and are outside the interview (for example, that of a researcher/professor and a company manager). In the interaction, these roles are often taken in turns, but they may conflict and overlap and may also become indistinct.

Further, our starting point is that any interview follows a dialogic structure and process through which the researcher and the researched actively negotiate their accounts in the research context and frame the representation of results (Pitman 286-287). Interviewing then is an active social interaction that leads to negotiated, contextually based accounts through a process of co-construction which draws on ongoing and negotiated relationships with the participant in all stages of research process—from the design to data collection to analysis and interpretation. What is less discussed in constructionist accounts of research interviews, is (a) the implications of the role of the researcher on the co-creation and the representation of research findings; and (b) the move beyond the co-produced accounts in the interview space to them being a proxy for representing practice in other domains of activity. We address both in turn.

The “Reflexive” Researcher in Co-Constructed Encounters

In the, by now, common approach to interviews as co-constructions, researchers are not invisible, neutral beings who endeavor to get the respondent to reveal the truth, but by interacting with the interviewee they inevitably become active agents in the process. Interviews, then, are not merely a series of asking and answering questions aiming at collecting objective data to be used neutrally for scientific purposes. Rather, they constitute an active (Holstein and Gubrium 4) and dynamic (Jonson and Rowlands 107) collaborative exchange that leads to a historically and contextually bound, mutually created story (Fontana and Frey 696). Interviews are acknowledged as complex, unique and unpredictable (Scheurich 241) encounters that may take unexpected turns, digress (Warren 140), and move both parties emotionally and/or empathetically as well as sympathetically (Fontana and Frey 697). In contrast to the positivist traditional epistemologies of condemning traces of bias and emotions in accounts, the empathetic approaches embrace both the inevitability and value of being involved.

In this light, the role of a researcher as a collaborator towards a mutually constitutive goal with the interviews entails a strongly reflexive attitude about what as well as how this mutually constitutive goal is being accomplished (Dingwall 51-60). A reflexive approach is actively seen as a strong desirable, something the interviewer trains themselves to do and is done during an interview and in retrospect, in the analysis of the data. Some ways this is accomplished involve acknowledging the possible, often inescapable, preconceptions of the interview, negotiations between the interlocutors, and affordances made by both parties during these negotiations. Typically, the interviewer is encouraged to be observant and monitor self in action when in interaction with interviewees and to be open-minded and flexible.

Further, being reflexive involves acknowledging the tendency to hear only what one’s ethical, experiential and subject disposition allows them to hear—to draw on one’s own commonsense knowledge to make sense and create a truth that will work for their own purposes. In an interview as mutual collaboration the researcher is supposed to take pains not to privilege any one way of looking at the world as there is no one truth sought to report, not even that of the interviewee, which the researcher hears or sees (Johnson and Rowlands 101). Adopting an empathetic attitude should not be a tool to get to elaborated responses. It is not “a method of friendship but of morality because it attempts to restore the sacredness of humans before addressing any theoretical or methodological concerns” (Fontana and Frey 697). In sharp contrast to traditional predetermined well-crafted and tightly structured agendas, in interviews as social interaction, interviewers are allowed to show their human side by answering questions, expressing feelings and talking about themselves. Part of this human side involves allowing digressions and going with the flow, which are more appropriate for unstructured and semi-structured formats of questioning. The researcher must be ready to adapt to the pace and topics that come up but also capable of returning to the predetermined agenda when needed. Trust can momentarily be broken and repaired—e.g., a patient be suddenly afflicted by confusion or memory loss, a senior manager may wish to assert his dominance over a female interviewer, and a working mother may be overwhelmed by a bout of drowsiness. A humanitarian approach to interviewing has at heart the acknowledgment of the nature of human interaction and the agency of the two parties involved.

Adopting a constructionist perspective entails, then, viewing all the above (and more) as inescapable, inevitable aspects of a social interaction; far from comprising ground for dismissing the interview data as unreliable. This is all well argued over the years and is convincing in the light of data of multiple studies under this epistemological position. What is less clear is: (a) what this actually means in practice, and (b) how we achieve it. The researcher is supposed to be reflexive of all those parameters of the event but the enactment of the above methodologically and analytically often remains fuzzy. Raising awareness of the need to be self-critical is certainly important for any research approach. Aphorisms like we summarized, however, indicate well-intended ideals of equality in the process of eliciting data, but the form they take and what they mean in practice is much less straightforward. As put by Carol Warren, “Sociologists [and social scientists more generally] are famous for pointing things out that they then ignore; the interactionally contingent aspects of the interview are among those things. We write methodological articles about these contingent aspects, and then go to analyze the data as if this were not so” (140, our note). We return to this position in the light of our data. Going further, approaching interview as an interaction bears direct implications on analytical dispositions. We turn to this next.

The Interview as a Process and a Product

Taking a reflexive approach to the interview has been associated with a better understanding of the interviewee’s point of view. Better in this context carries implications of accuracy, faithfulness and hence objectivity. This is represented in the ways the researcher-participant roles are captured in relevant scholarship (Breen 164; Roulston 278; Vähäsantanen and Saarinen 507). For instance, the interviewer is seen to take the role of an “attentively listening student” or getting “in the shoes of the interviewee” (Fontana and Frey 703). These metaphors are very useful in capturing the understanding of relationships of power between interviewer/ee (note here a student/teacher metaphor) and the function of the interview as an event that leads to a fuller or more complete account. Taking this further, the interviewee is still a carrier of a form of the truth that the interviewer can touch upon and the boundaries between the researcher/participant are well defined. The interaction/co-construction becomes a conduit or a mechanism for enhancing accuracy. Despite all the ideals of a negotiated floor, the interviewer is indirectly positioned as an agent of their organization, representing/illustrating positions that carry general validity.

This is a problematic assertion which contradicts what happens in a situated encounter in which each party creates the interactional context for the next turn. Perceiving the interview as social interaction necessitates understanding that both parties are contextually bound both prior and during the interview and they bring their respective roles and agendas to the encounter. The interviewers, on the one hand, can be well-trained or novice researchers with a keen interest in the research goal, accountable to supervisors and/or mentors, other collaborating researchers, funding sources: they can get to the interview feeling enthusiastic or burdened by a myriad of concurrent agendas. The interviewees, on the other, carry their own expectations of what will ensue and, regardless of having agreed to it, are subject to their own feelings. Research methodology literature has shown that participants who see in the interview a social event are more talkative and provide different type of narratives compared to others who associate interviews with social (or other) control. Similarly, structural and material characteristics play a critical role in the form and function of the interview. The time and place of the interview and contextual parameters play an equally important role. Participants interviewed at the end of a busy day who see the interview as a social event engage with the interview through a different prism (Machili, Writing 69), and having the interview late at night in one’s house with the spouse and kids at home will lead to a different event (see excerpt 1) from conducting it in the morning in an office. Also, the historicity and relationship between the two parties affect both the design of questions and responses according to whether there is a prior relationship between the two, the kind and depth of the relation (e. g. trusted colleague, distant acquaintance, family) or if the two are complete strangers. “Respondents come to the interview willingly (presumably), interested in the topic—and whatever lures are thrown out—to show up. But their agendas and understanding of what the interview is for, and how it unfolds, depend on the biographical and situated context of their lives-which, in turn, is also historically situated.” (Warren 133). The circumstances of the interview itself are a contextual factor. According to the empathetic approaches to interviewing, establishing trust and rapport (Fontana and Frey 708) is paramount for the interview to succeed as it is an in inevitable element of any fruitful or positive social interaction.

Further on this, drawing on the conversation analytic and interactional sociolinguistic tradition, interactants in an interview context will negotiate their situated role as well as professional and personal or social identities that they see relevant to the business at hand. An interview, as an interactional situated encounter then, could suggest that the account is a product of the interactional work of the two participants and carries little or no representability of behaviors in other domains of activity. This is a problematic position too. Interactants (both the researcher and the participant) are not tabula rasa prior to the event. They draw on their lived experience and expectations of what an interview should or could look like as well as their professional experience that drove them to the project in the first place. They, therefore, draw on the question-answer design of the interview as well as the capital of their lived experience. The referential value of the accounts very much depends on the topic and the researcher’s reading and the framing of the whole research project. We capture this process through data we use to illustrate the argument. The excerpt in this chapter represents patterns in the datasets, which more generally reflect the complexity of the positions the interviewers/ees take.

To sum up the discussion, instead of debating on a binary between constructionist and (post)positivist approaches, we advocate for a holistic research approach, according to which the researcher’s own understanding of the phenomenon shifts in and through the engagement with multiple datasets (Angouri, Culture 92; Machili, Writing 65, Pretty Simple 123). The research interview, in particular, provides the context for the researcher’s development and negotiation of pre-existing, situated and any other momentarily enacted roles, which apply to their own capacity for theorizing and shifting from describing a first order phenomenon (lay user) to a second order meta-account. The choreography between the interactants unlocks layers of meaning and allows for the development of a shared meta commentary between them which, in its turn, enables the researcher’s theorization. In other words, both the position of a better interview is accurate and the position of the interview as an interactional situated encounter. We argue that tools such as DBIs enable to capture the dynamic interface between first/second order. We discuss this next.

Negotiating First/Second Order Accounts in the Research Interview

A distinction between first and second order approaches is typically used to distinguish between a lay user’s and a researcher’s reading of a phenomenon. The distance between a common-sense (first order) view of a phenomenon and a second order constructed account is noted in literature and particularly in traditions such as ethnomethodology which oriented on the mundane experience (see Schutz 1-53). Alfred Schutz writes: “The thought objects constructed by the social scientists refer to and are founded upon the thought objects constructed by the common-sense thought of man [sic] living his [sic] everyday life among his fellowmen [sic]” (3).

Prioritizing the first order as well as the complexity of building accounts around it (second order) has long standing in socio/linguistic enquiry. Particularly researchers in politeness theory and pragmatics (e.g., Haug 251) have long engaged with how to best capture the analyst’s vs. speaker’s interpretation of a speech event. The first/second order concept has been heavily and usefully debated in those areas. It is also an issue well debated in relation to emic (insider) and etic (outsider) accounts of data. All those binaries—positivism/constructionism, process/product, first second/order—have been very valuable in challenging our thinking around the methods and theories for capturing data and the ensuing interpretation processes. None of those binaries in and by itself, however, can capture the complexity of meaning negotiation in the interview context as well as in the researcher’s own interpretation.

The researcher and the participants are involved in a choreography which is iterative. First order events and second order reflection of phenomena concern both the researcher and the participants constructing the here and now of their world as well what is preceding and following an event. The researcher’s own reflexive approach to their data, or the participants’ use of a meta language in subsequent research activities, become part of deconstructing and reconstructing their experience. A DBI approach is particularly relevant to this process.

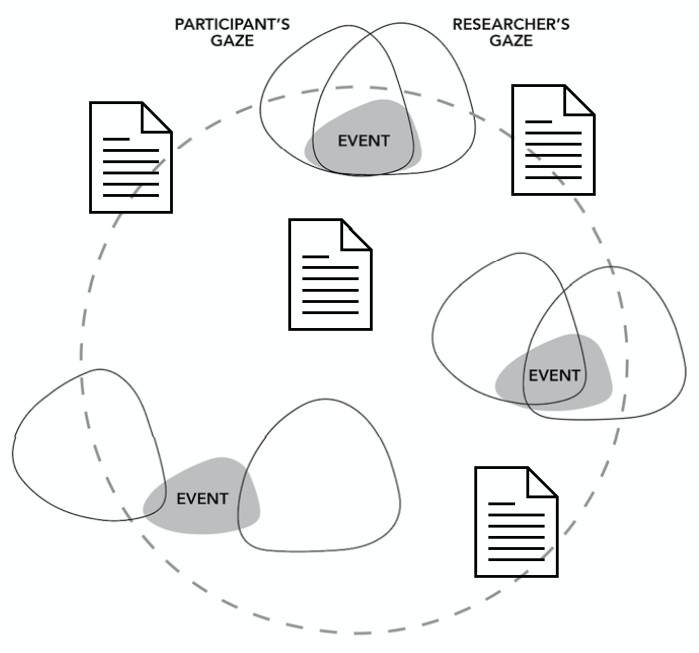

Figure 1. Graph showing how the narrative created by interviews is negotiated and co-created by participant and researcher: the participant's gaze, the researcher's gaze, the interview as an event, and the artefact involved.

The two actors of the event have different approaches and viewpoints by the nature of their roles and lived experience. Figure 1 represents the ongoing process of negotiation and co-creation of the narrative. When tools external to the (interview) event are used as stimuli by the researcher, they provide a reference which requires a recontextualization of practice in the interview event. The artefact, represented here as a written piece, is typically taken from the participants’ core domains of practice which the researcher has captured. The figure shows an abstraction of material recontextualized for the purposes of the event; the artefact then acts as a third actor, a referee, and provides a pathway into creating accounts and sharing experiences that would otherwise not be mobilized in the interview event. The interactants draw, challenge and perpetuate their own and each other’s perceptions in the interview frames which shift between the situated interview format (question/answer) and their non- situated role in providing accounts about the form and function of the artefact. We elaborate in relation to three established tools and the way they are used in our discipline below.

From Think Aloud to Stimulated Recall and Interactional sociolinguistics

Think aloud protocols were developed as an attempt to circumvent the influence and perception of the observer by obtaining verbal data directly from the participants concurrently with their performance of a task. Initially the method held much promise for easily eliciting detailed information on the sequential steps followed by the participants during the performance of the task (Ericsson and Simon 19). However, the method was soon criticized on two grounds: the interference (as well the presence of the researcher) caused by the verbalization could either disrupt and hamper the thinking process or even improve it particularly in highly interactive and dynamic settings thus altering the natural environment it occurs (Verplanck 133). This echoes observations by sociolinguists and notably Labov who described the observer’s paradox referring to the unintended influence on a phenomenon by a researcher (61). Given the strong positivist tradition at the time think aloud was growing, the difficulty revealing true feelings and accurately reporting what participants thought made the methods associated with judgement bias (Nisbett and Wilson 231-235). A number of modifications ensued as researchers tried to elicit not mere recalling of information but engaged the participants in reflection encouraging justifications and inferences by actively interacting with them during the task performance (Boren and Ramsey 270) or analyzed participant transcripts retrospectively (Ericsson and Simon xvi; Yang 101). All the above evidently raise a number of what was perceived as validity issues for concurrent collection of verbalization and ultimately led to the development of retrospective methods using the aid of a stimulus.

In stimulated recall protocols the participants were allowed to complete the task naturally and then asked to verbalize their thoughts using the aid of a stimulus, which in most cases was a videotape but could also be an audiotape, a transaction log, a picture, a completed questionnaire, or a piece of their own writing. Following shortly after the performance of the task, this would aid the recall of the original thought processes accurately and even engage the participants in retrospective (critical) reflection on why they acted the way they did and possible alternative choices at the time of the event. The method became widely adopted yet adapted to suit different research contexts such as counselling (Kagan et al. 5-6), chess playing (Calderhead 213), medicine and nursing (Daly 123-124), and sport coaching (Lyle 868-871), and was used extensively in language teaching (Gass and Mackey 28-40). Some variations in its implementation include using semi-structured or more focused questions and thought listing, use of static or head-mounted cameras (to accommodate classroom or more dynamic and complex settings) and audio recorders, and interviewing the participants immediately after the video is played or during multiple playbacks of audio recordings. Despite the advantages of its wide flexibility, of not tampering with the naturalistic setting of data collection and of allowing the participants to recall and critically reflect on their cognitive processes, the tool has also continued receiving criticism. One is still echoing the positivist/post-positivist school of thought and concerns “a number of possible biases in judgment” (Hoffman et al. 147-149) evident in what is perceived as lack of consistency in reports, adoption of a favorable image, and trying to conform to the researcher’s expectations/goals. These are said to emanate from feelings of anxiety and discomfort from viewing a videotape of their behavior, the limitations of visual cues recorded, and the new altered and enriched perspectives elicited from reflecting on the videoed experience (Calderhead 213; Yinger 273-280). All the above are perceived as problems to the tool’s validity and reliability (Gass and Mackey 13-14).

The ideological dispositions of positivism and the emphasis on attempting objectivity is directly relevant to the framing of the use of the tool. The most salient issue from the point of view for our discussion is the focus on the participant, and the effort to minimize the interference of the researcher and the tampering of original data collection from a naturalistic setting. The tacit knowledge to be elicited is perceived as objective quantifiable information that is transported, rather than constructed, and is not to be tampered with or else issues of reliability and validity arise. The researcher and the procedure were supposed to be as unobtrusive as possible, yet solutions advise the establishment of rapport between researcher and researched. Although a researcher’s previous familiarity with a research setting may be beneficial both in terms of establishing rapport, gaining a better understanding of the area under investigation and even facilitating the research procedure (e.g. for John Lyle’s volleyball coaches), the language used around the method is indicative as the researcher is encouraged to not “contaminate the process” (873). These positions are all products of the underpinning, dominant epistemological paradigms of their time. At the same time and despite the deterministic nature of the underpinning rationale, selecting a range of practices that emerge from the data, and allowing the participants to frame what is more or less relevant to them, undoubtedly constitutes good practice. A context-sensitive approach enhances the depth of participants’ accounts by enabling the core actors to position themselves and practices in their setting.

Around the same time sociolinguistics as a subdiscipline of linguistics continued to grow, John Gumperz developed and introduced a theoretical and analytical framework connecting linguistic analysis with the social world within which speakers interact, interactional sociolinguistics (IS). IS focuses on a detailed analysis of situated encounters. It analyzes linguistic resources mobilized in interaction with the wider social order. This is through a systematic analysis of social meaning associated with the cues speakers mobilize. IS offers a theory of context as it enables the researcher to move between the here and now of interaction to the wider sociopolitical order. The researcher has the tools to move away from “spotlighting” the participant and creates space for a holistic and humanitarian approach to understanding complex phenomena.

Gumperz (223) suggested a staged approach to IS involving five levels. In more detail:

-

Insight into the local communicative ecology [involving landscaping the characteristics and norms that apply to events relevant to the community];

-

Identification of recurrent encounter types;

-

Emic perceptions of the problems/issues and ways of handling them;

-

Detailed analysis of interaction;

-

Playback-playing recordings to those participating in a project.

The last is relevant here as it was conceived to provide a method for involving the participants in providing accounts for language use. Playback techniques, in their most basic format, involve playing video or audio recordings of interaction back to those involved in an encounter and invite their interpretation. This process is intended to be exploratory and empowering for the participants. Playback techniques have been operationalized differently in different studies, and in recent years they have allowed for the reflexivity project, i.e. for researchers to work with professionals in a variety of settings in exploring issues around daily life at work. We consider IS to be well aligned with the ethos and rationale of DBI to which we turn next. IS provided us a method to analyze DBI tools as an object of analysis which shows how multiple frames are mobilized and become relevant to the participants. Beyond this, however, we take a broad approach and consider those variations as useful designs that need to be shared more broadly for DBIs and to become established in the social sciences toolkit. We discuss this further next.

DBIs

DBIs’ most common approach involves showing the participants actual pieces of their own writing and inviting them to talk through alternatives. The DBI, in line with the other tools, was conceived and applied to provide accurate and unbiased insights into the participants’ reality and capture lay user’s accounts. The importance of such first rather than second order concepts has been highlighted by various sociolinguists concerned with the study of written discourse (e.g., Angouri & Bargiela-Chiappini 212). The DBI has also been warmly embraced by linguists as it provides the opportunity to engage with data retrospectively without impacting the act of producing naturally occurring discourse.

Similarly to earlier discussion, DBIs can provide access to contextual information not present in the text, which is necessary for our understanding of the writers’ rhetorical accounts/aspiration or intentions. It is aligned with the emic ideal, the insider’s view contrasted with that of the “observer looking on” (Widdowson 6). By addressing questions like “why does X happen here?” and “I see in other places you do Z. Would you be willing to do Z than X?” with reference to their own writing and in recontextualizing practice outside the interview context, writers, in principle, tap into the conscious and a good part of the subconscious level of their intentions (Odell et al. 223).

Despite the initially apparent similarity to the think aloud/playback designs, DBIs focus exclusively on writing which is a significant differentiation and particularly relevant for linguistic research as written texts often remain secondary or get sidelined. Although the emphasis has been historically on participants’ view, DBIs have been more open to the ways in which researcher and participants are actively involved contributing more or less equally to the elicitation of the data/interviewing process. Departing slightly from Odell, Goswami, and Herrington’s tightly structured format (223), the use of a semi-structured design allows both parties to develop the conversation freely in addition to addressing a number of predetermined questions. The participant is given time and space to elaborate more on aspects that s/he deems important and relevant, and the researcher is ready to ask questions that are prompted from the participant’s responses as the interview develops. As research has indicated, being shown instances of their own texts, participants are willing to go in detail about why they acted the way they did, be open about it and despite the situated encounter they adjust their response less to what the researcher might want to hear or the research project aims (Harwood, (In)appropriate 430, Interview-Based 501; Machili, Pretty Simple 124).

The appeal and flexibility of DBIs are evident in the substantial body of researchers who have used them to investigate a variety of contexts making several adaptations to Odell et el. (1983) original version and affording different roles to the researcher. Areas investigated through DBIs vary widely including scientific and academic writing (Olinger 460) and digital texts (Gallagher 20-21). Work by Harwood on use of pronouns and citations in academic writing (Petric and Harwood 112; Harwood, (In)appropriate 429, Interview-Based 500) has adopted an emic perspective by unearthing the participants’ intentions behind instances of their writing yet allowed both the researcher and the participant to become actively involved in the conversation. In these studies, having read the texts, the researcher prepares a number of questions to ask in the interview but also allows the participant to elaborate on points of their choice. In his examination of one student’s use of stance, for example, Lancaster uses corpus-based analysis to prompt the questions to use in the interview. This, from a (post)positivist perspective, could give objectivity to a procedure that has been criticized for its subjective thrust (143). What is more dynamic, however, is that DBI enables the participants to theorize and create accounts with the researcher, and first and second order accounts become co-constitutive in the interview context.

In summary, what those designs provide is a dialogue between the researcher and the participant as well as the artefact which connects the interview event with practice captured in other aspects of the participants’ realities (see Figure 1). Moving beyond the binary of an interview as the process or the product, the DBI opens the floor and provides a structural component to enable both researcher and participant to design their accounts with reference to an artefact. The interactants then negotiate the interviewer/interviewee role; their non-situated professional roles; their relationship with the stimulus. Through this process of negotiating their encounter, a participatory approach to the agenda which brings together first and second order accounts emerges. The interview becomes a performance and a performative, a co-construction between the participant and interviewer and a recontextualization of pieces of the world in the interview event (Edley and Litosseliti 157). The DBI then, reframed in the way we discuss here, enables the researcher to move beyond a static binary between written and spoken artefacts and engage holistically with the participants’ ecology.

As an illustration of the DBI potential for holistic research we draw on our ongoing research on workplace writing and the enactment of formality in workplace emails in five multinational companies in Greece.

The data is collected from 18 DBIs, where the participants were invited to reflect on the form and function of their own emails and articulate their linguistic choices. The focus of that work has been on exploring the ways in which professionals use linguistic formality to claim their roles and navigate power asymmetry in their context. The purpose of the excerpt below is to show a worked example of DBI and its capabilities. The excerpt we have selected is representative of our interview data set in the linguistic features and contexts identified as well as of the multi-layered significance of the interpersonal relation between interviewer, participant and artefact.

The DBI Interview as a Dynamic Space for Role Negotiation

We look here at how role negotiation is actively done in a discourse-based interview with the researcher as the interviewer, where the participants talk about their use of (in)formal linguistic features and contexts in their own emails. Note that the language around formality has been introduced already in participant information documents and consent forms. As formality carries strong first order connotations, the participants already had a metalanguage to theorize in response and in anticipation of the researchers’ questions. We discuss the study itself elsewhere (Machili, Writing 89, 142-207). Here we will show how the participants orient towards their situated, pre-existing and social roles and the artefact.

Background: This interview is between prior acquaintances. The interview is taking place in Mary’s house with her two kids in their room playing and her husband in the next room working. She has just finished cooking and put the food in the oven. It’s 10:00 at night, she is tired after a long day, and the interviewer is tired too. Going to her place at that time was the only free time she had. She works for a multinational pharmaceutical company.

Table 1. Excerpt showing exchange between Mary (M, participant) and interviewer (I).

|

Lines |

Interactants’ exchanges |

|---|---|

|

1 |

M: [points at a particular email] let’s look at this email see if... there is |

|

2 |

anything here. |

|

3 |

I: ok how formal would you say this is? |

|

4 |

M: well this [email] I would say is something informal between my |

|

5 |

colleague George and me about where we should meet. |

|

6 |

I: what do you mean by informal? |

|

7 |

M: I mean it’s just between George and me. |

|

8 |

I: so you’re saying it’s personal communication? |

|

9 |

M: yeap personal informal not formal the whole world doesn’t have to |

|

10 |

know where we’ll meet. |

|

11 |

I: Can you show me where is this informality? where does it show? |

|

12 |

M: [looks at email] well it’s everywhere there’s [points at a phrase |

|

13 |

in one email] here “how’s 10” is something I would write to ... |

|

14 |

[stops speaking and looks at her watch] ups it’s 10 already I just |

|

15 |

remembered I need to turn the oven off [leaves & comes back] we’re |

|

16 |

having roast chicken and potatoes tomorrow for the kids mainly ... you? |

|

17 |

I: no idea not yet. |

|

18 |

M: so we were saying? My job is killing me. |

|

19 |

I: it is, isn’t it? the food ok? |

|

20 |

M: yea yea |

|

21 |

I: [silence] we were talking about “how’s 10” how informal this is and |

|

22 |

who you would say it to. |

|

23 |

M: right ... well to my colleague George ... we work together in the |

|

24 |

same office we get along he’s nice ... there is no salutation it’s just two |

|

25 |

words “how’s 10” it’s like ... you know talking to you I would write the |

|

26 |

same thing to you. |

|

27 |

I. Mary we’re friends we don’t arrange our meetings in emails we use |

|

28 |

the phone [laughs] |

|

29 |

M: [silence frowning] |

|

30 |

I: [laughs] gotcha there. |

|

31 |

M: [laughs] got it ... hm to you I would just text “10”. |

|

32 |

I: why’s that ? everything else is implied you mean ? |

|

33 |

M: well yea we understand each other. |

|

34 |

I: or do you mean it’s not a sentence? |

|

35 |

M: well both actually we don’t use sentences do we? [silence] but to my |

|

36 |

manager I would write “Could we meet at 10?” to my colleagues in the |

|

37 |

other departments I think I would write “how about?” ... something like |

|

38 |

that. |

|

39 |

I: so |

|

40 |

M: so it really depends on who you’re talking to ... and for what reason |

|

41 |

it’s not black or white. |

|

42 |

I: formal or informal |

|

43 |

M: well obviously there are degrees of formality. |

|

44 |

I: like a continuum |

|

45 |

M: yea for example “dear” is very formal for us I would place it at the |

|

46 |

one end of the continuum ... I would use it with people I don’t know |

|

47 |

mostly prospective clients but not with my boss not in this company |

|

48 |

[looks at other emails] let me see I’m trying to find something ... |

|

49 |

something more professional ... more formal ... hm I think this email |

|

50 |

[points at another email] has more to give us |

|

51 |

ok let’s focus now ... |

|

52 |

[silence] my job is killing me |

The exchange shows the dynamic between roles that are at play: the situated and preexisting social roles of the interviewer, the participant, and the artefact (the emails and their specific linguistic features in our case). The relationship between those involved, with its historicity long or short, plays an active role in the research agenda and affects the parties’ lived experience and accounts.

The exchange here starts with both parties referring to the artefact (lines 1-13). The interviewer asks questions about the formality of the specific email and Maria, as participant, elaborates on the informal context in which the email is written, an instance of personal communication between her and her close colleague. As the question-answer sequence moves from the context of the email to its linguistic features, however, the email phrase “how’s 10” triggers an interruption of topic as the participant remembers it’s 10:00 and time to turn the oven off. The topic shifts to a short social discussion about food and the participant’s job between two friends (lines 14-20). It soon returns to a discussion of the linguistic features, “how’s 10” and the absence of salutation, in lines 21-26, and is yet interrupted again by a friendly joke this time initiated by the interviewer (lines 27-31). We see the artefact gaining a prominent role in the interaction by triggering changes in the topics from the informal context of email to the food (lines 14-20), from the food back to the linguistic feature of “how’s 10” (line 21-26), further to the joke (lines 27-31), and back to the linguistic features of (in)formality (lines 32-47).

The artefact is also seen to trigger first and second order accounts in the interaction. The references to the informal context of the email, as an instance of personal communication among colleagues, (lines 4, 5, 7) constitutes a first order account that in turn leads to an explanation of its informality (lines 9, 10), the theorization that personal communication between fellow workers is considered an informal yet acceptable organizational context/situation. Further the references to the specific linguistic feature “how’s 10,” the participant’s first order account, triggers further lay yet detailed accounts in “to you I would just text “10,” “to my manager I would write “Could we meet at 10?” to my colleagues in the other departments I think I would write “how about? ...” as well as similarly specific second order accounts in “we understand each other,” “well both we don’t use sentences do we ?.” As the analysis unfolds, deeper/more theorization of practice ensues by both participant and interviewer as they conclude that formality is not a matter of black or while, formal or informal, but more like choices in a continuum (lines 40-44). These second order accounts, which are initially stirred by the linguistic features present in the email at hand (artefact), then trigger further first and second order accounts of the use of “dear,” a linguistic feature not present in the email at hand but frequently used by the participant in other contexts. Mary’s narrative starts with her theorization in “dear” is very formal for us I would place it at the one end of the continuum ...” and then moves to her lay description of whom she would use it with in “I would use it with people I don’t know mostly prospective clients but not with my boss not in this company.” Interestingly it is these accounts that make her want to look for other “more professional ... more formal” artefacts to discuss.

Similarly, in the beginning of the exchange (lines 1-2), Mary also picks a specific email to discuss. By picking specific artefacts for topic of discussion and justifying her choice in “let’s look at this email see if ... there is anything here” and “let me see I’m trying to find something ... something more professional ... more formal ... hm I think this email [points at another email] has more to give us,” Mary transcends a first order account to a second order theorization of practice. As the exchange shows, first and second order accounts, initially stirred by the artefact at hand, precede and follow each other and trigger the choice of future artefacts in a process that is more iterative than linear.

This exchange further expands to the pre-existing and situated roles the two parties adopt. The parties alternate between their initial situated interviewer-participant role and their pre-existing respective social roles of friends/social acquaintances. The beginning of exchange finds the two parties in their situated participant-interviewer roles (lines 1-13) discussing the email in terms of context. Triggered by the phrase “how’s 10,” these roles shift to pre-existing ones of friends (lines 14-20), and then go back to discuss the artefact in terms of linguistic features as interviewer-participant, return back to friends again, participants-interviewer and the exchange ends with “My job is killing me” in her role as a friend.

These roles, however, are not always distinct. In “‘how’s 10’ it’s like ... you know talking to you I would write the same thing to you,” Mary explains the use of the particular phrase as both an interview participant and a friend. As these roles overlap, they become indistinct and may even cause possible misunderstandings. The interviewer responds laughingly with a joke “Mary we’re friends we don’t arrange our meetings in emails we use the phone,” a social yet corrective and evaluative comment that is followed by Mary’s frown and silence. The interviewer’s ensuing laugh together with “gotcha there,” however, clarify that the intention was to make a joke between friends. Mary’s laughter and response in “got it” make the atmosphere lighter and the act is rendered an act of social bonding and collegiality, instead.

Further, the traditional interviewer-question initiator and participant-respondent format is not retained as the participant shares feelings of tiredness with her job (lines 18, 52) that may potentially disrupt the question-answer sequence if taken up by the interlocutor. Similarly, the participant is not a mere vessel of information the interviewer seeks. She resists situated positions, actively selects parts of the lived experience to theorize on practice and engages in social talk with the interviewer. Multiple analytical procedures follow and emerge from DBI encounters. In the case of our work, the richness of the data enabled us to both identify patterns on frequency and correlation of appearance as well as offer accounts drawing on the lived experience of all participating stakeholders, both the researcher and participants. We combined measuring patters as per traditional thematic analysis with a detailed analysis of the artefacts themselves. The multi-method treatment of the data enabled us to go beyond a QUAN/QUAL approach, and we provide some examples of the resulting representations of the data analyses in the appendix. Appendix 1 shows a qualitatively derived thematic analysis of formal and informal linguistic features used in workplace emails. Appendix 2 illustrates a quantitatively derived collection of formal and informal linguistic features in an email corpus (Machili et al. 29, 31)

In sum, the two parties orient towards producing a joint account by negotiating actively their situated and pre-existing social roles and by co-addressing the artefact. The artefact becomes more than a stimulus. It becomes an active agent that sets the conditions for and affects the event. It necessitates a deeper level of description (first order account) than one we would have without it and theorization (second order account), a pattern we see across our data set. The artefact becomes a structural component of the event, which, through its agency, makes the interactants alternate and mix roles, affects the specificity of their narratives and leads to second order accounts. We claim that the agency of the artefact can be conceptualized as a third participant across the data set and a core enabler in a multi-method perspective (Figure 1). By being taken away from its pre-existing organizational context and recontextualized in the interview environment, it provides windows into the prior- as well as the situated lived experience from the perspective of what they are doing and co-constructing the situated moment and of the narratives they provide. The DBI creates a (safe) context for those accounts to be co-created and the participants’ relationships to be negotiated in situ. We summarize this discussion in the next and final section of the article.

Discussion and Concluding Remarks

We have argued that a DBI approach, and ensuing research designs, can go beyond static binaries that fail to capture the dynamic of phenomena research seeks to address. Our work in workplace writing, particularly on workplace email, shows the importance of collaborative framing of the interpretation of and theorization from data in which the participants are co-creators; through this process researcher and researched are in a meaningful process of on-going negotiation. Although complex, this process provides pathways into capturing the complexity of the lived experience in modern organizations. This increases the depth of research outcomes and carries potential for applying results for the benefit of the participants.

Against this backdrop, DBI is best understood as a framework and not a single method. Any of the designs we discussed in this article can provide the researcher with valuable tools for exploring nuances in their topic area. They enable a dynamic co-construction of first and second order accounts which usefully draws on tools and methods that are associated with QUAN/QUAL/MIX paradigms and relevant stances play a role in unlocking and unpacking different layers of meaning. We have shown elsewhere a visual metaphor of the possible differences between first/second order worldviews and theorization. In the light of the discussion here, we argue that these positions are dynamic and are shifting in the timeline of the encounter as well as during the lifecycle of the process. In Figure 1 we represented the fluidity between first/second order positions. This process is ongoing and changes as participants develop common frames of reference.

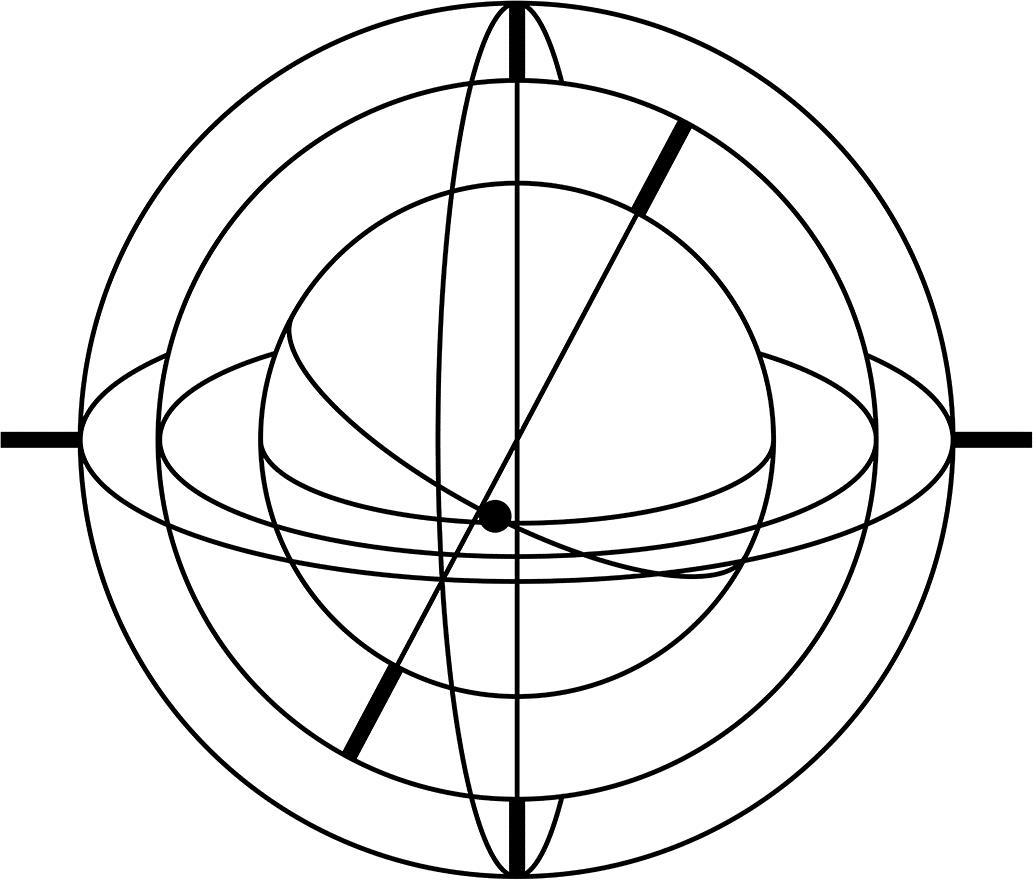

Capturing more layers of the individual knowledge is, currently, a target for researchers, and the increasingly adopted MIX approach is presented as a solution to capture the so-called best of both worlds in the QUAL/QUAN spectrum. We certainly welcome the essence of using the previous worlds as a springboard to reach deeper and analytically richer readings of research. Elsewhere (Angouri, Culture 79) the metaphor of Eudoxus’s rotating spheres has been used to provide an illustration of the research process as nesting concentric spheres each of which are connected to a centre, the researcher’s gaze. Eudoxus’s spheres do not turn in the same direction, which provides a continuation of the process we described in Figure 1. The multilayered and shifting nature of the research reveals further angles as it unfolds and is always related to relationship between the researcher and the researched.

Figure 2. Visual of Eudoxus’s concentric, rotating spheres from Angouri, Culture, with multiple spheres rotating around the gaze of the researcher.

To achieve this perspective we need to shift from static and essentialistic understandings of the researcher and participant to looking into, in this case, the interview as an interactional domain of activity where both situated and wider roles and knowledge emerge and become object and subject for further analysis. This is essential for multi-method, multi-layered research which will democratize research agendas and move from binaries to a system of participatory research where the participants are truly freed from being directly or indirectly positioned from a passive bearer of information to an active agent in the research practice.

DBIs as a framework and ensuing methodology allows the systematic use of artefacts and offers the DBI encounter itself as an object of analysis. A repositioned DBI can provide social science research with new insights on topics of investigation but also new methodological and analytical tools for collaborative research with (non-academic) professionals. Despite the volume of writing on the significance of reflexivity and making research accessible to all, we have not yet achieved ongoing and systematic collaboration with research participants. This is necessary in order to address the complexity of professional domains, such as the workplace, and to provide solutions to real world issues. Current moves such as open science advocate for and aspire to bring research to the wider population. The DBI is very much ahead of the trend and is providing linguists, and more broadly social scientists, with a versatile tool that can become more established and discussed in research method training. We hope our article makes a contribution to this agenda and invite future research to continue elaborating.

Appendices

- Appendix 1: Uses of (In)formal Linguistic Features

- Appendix 2: Association of Selected Linguistic Features of Formality and Informality

Appendix 1: Uses of (In)formal Linguistic Features (PDF)

Appendix 2: Association of Selected Linguistic Features of Formality and Informality

|

Types of linguistic features |

Associated with formality |

Associated with informality |

|---|---|---|

|

Reference |

Corporate & collective “we” Collective & impersonal reference Impersonal & passive structures |

Individualized “I” & “you” Individualized reference Personal structures & active voice |

|

Fullness of linguistic forms |

Full forms |

Contractions, abbreviations, elliptical language |

|

(In)tolerance of grammatical errors |

Attention to grammatical correctness |

Tolerance of grammatical errors |

|

Lexical register |

Technical scientific & formal diction Standardized phrases Unemotional detached diction |

Conversational, colloquial diction Innovative, unconventional language Powerful, emotionally charged diction |

|

Organizational clarity & complexity |

Clear & linear paragraphing Long sentences variable in structure |

Loose, absent paragraphing Short, simple terse sentences/phrases Excessively long & loosely connected sentences Unconventional disruptive structure |

|

Degree of explicitness |

Explicit language |

Implicit language (minimal content, pronoun use) |

|

Degree of directness |

Fronting/Backgrounding Indirectness in speech acts |

Directness Directness in speech acts |

|

Greetings |

Impersonal |

Personal Absence of greetings |

Works Cited

Angouri, Jo. Culture, Discourse, and the Workplace. Routledge, 2018.

---. Quantitative, Qualitative, Mixed or Holistic Research? Combining Methods in Linguistic Research. Research Methods in Linguistics, edited by Lia Litosseliti, Bloomsbury Publishing, 2018, pp. 35-55.

Angouri, Jo, & Fransesca Bargiela-Chiappini. ‘So What Problems Bother You and You Are Not Speeding up Your Work?’ Problem Solving Talk at Work. Discourse & Communication, vol. 5, no. 3, 2011, pp. 209-229. https://doi.org/10.1177/1750481311405589.

Atkinson, Paul, and David Silverman. Kundera’s Immortality: The Interview Society and the Invention of the Self. Qualitative Inquiry, vol. 3, no. 3, 1997, pp. 304-325. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780049700300304.

Boren, Ted, and Judith Ramsey. Thinking Aloud: Reconciling Theory and Practice. IEEE Transactions on Professional Communication, vol. 43, no 3, 2000, pp. 261-278. http://doi.org/10.1109/47.867942.

Breen, Lauren. The Researcher ‘in the Middle:’ Negotiating the Insider/outsider Dichotomy. The Australian Community Psychologist, vol. 19, no.1, 2007, pp. 163-174.

Bryman, Alan. The Debate about Quantitative and Qualitative Research: A Question of Method or Epistemology? British Journal of Sociology, 1984, p. 75-92. https://doi.org/590553

Calderhead, James. Stimulated Recall: A Method for Research on Teaching. British Journal of Educational Psychology, vol. 51, no 2, 1981, pp. 211-217. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.2044-8279.1981.tb02474.x.

Daly, William M. The Development of an Alternative Method in the Assessment of Critical Thinking as an Outcome of Nursing Education. Journal of Advanced Nursing, vol. 36, 2001, pp. 120–130. https://doi.org/10.1046/j.1365-2648.2001.01949.x.

Dingwall, Robert. Accounts, Interviews, and Observations. Context and Method in Qualitative Research, edited by Gale Miller and Robert Dingwall, Sage, 1997, pp. 51-65.

Edley, Nigel, and Lia Litosseliti. Contemplating Interviews and Focus Groups. Research Methods in Linguistics, edited by Lia Litosseliti, Continuum, 2010, pp. 155-179.

Ericsson, K. Anders, and Herbert, A. Simon. Protocol Analysis: Verbal Reports as Data, revised edition, Bradford Books/MIT Press, 1996.

Fontana, Andrea, and James Frey. The Interview: From Neutral Stance to Political Involvement. The Sage Handbook of Qualitative Research, 3rd edition, edited by Norman, K. Denzin and Yvonna Lincoln, Sage, 2005, pp. 695-727.

Gallagher, John. Update Culture and the Afterlife of Digital Writing. University Press of Colorado, 2020.

Gass, Suzan. M., and Alison Mackey. Stimulated Recall Methodology in Second Language Research. Routledge, 2017.

Gubrium, Jaber F., and James A. Holstein. Narrative Practice and the Transformation of Interview Subjectivity. Handbook of Interview Research: Context and Method, Sage, 2012, pp. 27-43

Gumperz, John. Interactional Sociolinguistics: A Personal Perspective. The Handbook of Discourse Analysis. 2nd edition, edited by Deborah Schiffin, Debora Tannen & Heidi Hamilton, Blackwell, 2003, pp. 215-228.

Harwood, Nigel. (In)appropriate Personal Pronoun Use in Political Science: A Qualitative Study and a Proposed Heuristic for Future Research. Written Communication, vol. 23, no. 4, 2006, pp. 424-450. https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088306293921.

Harwood, Nigel. An Interview-Based Study of the Functions of Citations in Academic Writing across Two Disciplines. Journal of Pragmatics, vol. 41, no. 3, 2009, pp. 497-518. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2008.06.001.

Haugh, Michael. Conversational Interaction. The Cambridge Handbook of Pragmatics, edited by Keith Allan and Kasia M. Jaczcolt, Cambridge University Press, pp. 251-274.

Hoffman, Robert. R., Nigel, R. Shadbolt, Mike, A. Burton, and Gary, Klein. Eliciting Knowledge from Experts: A Methodological Analysis. Organizational Behavior and Human Decision Processes, vol. 62, 1995, pp. 129–158. https://doi.org/10.1006/obhd.1995.1039.

Holstein, James A., and Gubrium, Jaber. F. The Active Interview. Sage, 1995.

Johnson, John M., and Timothy Rowlands. The Interpersonal Dynamics of In-depth Interviewing. The Sage Handbook of Interview Research, 2nd edition, edited by Jaber F. Gubrium, James A. Holstein, Amir B. Marvasti, and Karyn D. McKinney, Sage, 2012, pp. 99-113.

Kagan, Norman et al. Studies in Human Interaction: Interpersonal Process Recall Stimulated by Videotape. Michigan State University Press, 1967.

Lancaster, Zak. Using Corpus Results to Guide the Discourse-Based Interview: A Study of One Student’s Awareness of Stance in Academic Writing in Philosophy. Journal of Writing Research, vol. 8, no. 1, 2016. http://doi.org/10.17239/jowr-2016.08.01.04.

Labov, William. Sociolinguistic Patterns. No. 4. University of Pennsylvania Press, 1972.

Lyle, John. Stimulated Recall: A Report on Its Use in Naturalistic Research. British Educational Research Journal, vol. 29, no. 6, 2003, pp. 861-878. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192032000137349.

Machili, Ifigeneia. ‘It’s Pretty Simple And in Greek...’: Global and Local Languages in the Greek Corporate Setting Multilingua, vol. 33, no. 1-2, 2014, pp. 117-146. https://doi.org/10.1515/multi-2014-0006.

---. Writing in the Workplace: Variation in the Writing Practices and Formality of Eight Multinational Companies in Greece. Diss. University of the West of England, 2014.

Machili, Ifigeneia, Jo Angouri, and Nigel Harwood. The Snowball of Emails We Deal with: CCing in Multinational Companies. Business and Professional Communication Quarterly, vol. 82, no. 1, 2019, pp. 5-37. https://doi.org/10.1177/2329490618815700.

Nisbett, Richard E., and Timothy D. Wilson. Telling More Than We Know: Verbal Reports on Mental Processes. Psychological Review, vol. 84, no. 3, 1977, pp. 231-159. https://doi.org/10.1037/0033-295X.84.3.231.

Odell, Lee, Dixie Goswami, and Anne Herrington. The Discourse-Based Interview: A Procedure for Exploring the Tacit Knowledge of Writers in Nonacademic Settings. Research on Writing: Principles and Methods, edited by Peter Mosenthal, Lynne Tamor, and Sean A. Walmsley, Longman, 1983, pp. 220-236.

Olinger, Andrea R. On the Instability of Disciplinary Style: Common and Conflicting Metaphors and Practices in Text, Talk, and Gesture. Research in the Teaching of English, vol. 48, no. 4, 2014, pp. 453-478.

Petrić, Bojana, and Nigel Harwood. Task Requirements, Task Representation, and Self-reported Citation Functions: An Exploratory Study of a Successful L2 Student’s Writing. Journal of English for Academic Purposes, vol. 12, no. 2, 2013, pp. 110-124. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jeap.2013.01.002.

Pitman, Gayle, E. Outsider/Insider: The Politics of Shifting Identities in the Research Process. Feminism & Psychology, vol. 12, no. 2, 2002, 282-288.

Rouston, Kathryn. Interactional Problems in Research Interviews. Qualitative Research, vol. 14, no. 3, 2014, pp. 277-293. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112473497.

Scheurich, James J. A Postmodernist Critique of Research Interviewing. Qualitative Studies in Education, vol. 8, 1995, pp. 239-252. https://doi.org/10.1080/0951839950080303.

Schutz, Alfred. The Problem of Social Reality: Common-Sense and Scientific Interpretation of Human Action. Philosophy and Phenomenological Research, vol. 14, 1953, pp. 1-38. http://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-010-2851-6_1.

Silverman, David. How Was It for You? The Interview Society and the Irresistible Rise of the (Poorly Analyzed) Interview. Qualitative Research, vol. 17, no. 2, 2017, pp. 144-158. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794116668231.

Strang, Ruth. Chapter VIII: The Interview. Review of Educational Research, vol. 9, no. 5, 1939, pp. 498-501. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543009005498.

Vähäsantanen, Katja, and Jaana Saarinen. The Power Dance in the Research Interview: Manifesting Power and Powerlessness. Qualitative Research, vol. 13, no. 5, 2012, pp. 493-510. https://doi.org/10.1177/1468794112451036.

Verplanck, William S. Unaware of Where’s Awareness: Some Verbal Operants- Notates, Moments and Notants. Journal of Personality, vol. 30, no. 3, 1962, pp. 130-158.

Warren, Carol, A. B. Interviewing as Social Interaction. The Sage Handbook of Interview Research, 2nd edition, edited by Jaber Gubrium et al., Sage, 2012, pp. 129-142.

Widdowson, Henry G. On the Limitations of Linguistics Applied. Applied Linguistics. Vol. 21, no. 1, 2000, pp. 3-25. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/21.1.3.

Yang, Sue Ching. Reconceptualizing Think Aloud Methodology: Refining the Encoding and Categorizing Techniques via Contextualized Perspectives. Computers in Human Behavior, vol. 19, no. 1, 2003, pp. 95-115. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0747-5632(02)00011-0.

Yinger, Robert J. Examining thought in Action: A Theoretical and Methodological Critique of Research on Interactive Teaching. Teaching and Teacher Education, vol. 2, no. 3, 1986, pp. 263-282. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0742-051X(86)80007-5.

Discourse-Based Interviews from Composition Forum 49 (Summer 2022)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/49/linguistic-discursive-research.php

© Copyright 2022 Jo Angouri and Ifigeneia Machili.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 49 table of contents.