Composition Forum 53, Spring 2024

http://compositionforum.com/issue/53/

Nurturing Distributed Expertise with Social Media in First Year Composition Pedagogy

Abstract: This article offers composition theorists and practitioners insight into how social media pedagogies can help support the development of distributed expertise in writing classrooms. Reporting on the findings of an IRB-approved qualitative case study, this article showcases how students learning from and alongside one another in a Slack social media learning environment can enact distributed expertise within the classroom. After reviewing the study’s findings and contributions, the article offers some “best practices” for supporting distributed expertise with social media pedagogies in composition courses. It closes by considering social justice implications for social media pedagogies, distributed expertise, and composition pedagogy.

In common parlance, expertise is a term that often connotes professionalism, experience, competence, knowledge, and know-how. In academic settings such as college classrooms, expertise commonly celebrates the formal credentials, authority, and professional acumen of the expert professor. This somewhat traditional understanding of expertise lends itself well to sage-on-the-stage models of learning characterized by the expert professor imparting knowledge, wisdom, insight, and judgment to onlooking students sitting passively at their desks.

In recent years, however, some in academic settings and beyond have begun to rethink expertise, working to factor elements beyond formal credentials and institutional affiliations into how expertise is understood, conceptualized, and enacted in learning and education (Ito et al., 78; Wardle and Scott; Geisler; Glotfelter, Updike, and Wardle; Reed; Hartelius). One approach to reconsidering how expertise works in communities and classrooms, distributed expertise, recognizes the immense value of oft-neglected expertise-creating elements such as personal experiences, cultural knowledge, positionality, and individual interests, passions, and curiosities (Langer-Osuna and Engle; Tucker-Raymond et al.; Cassidy et al.). Similarly, distributed expertise in educational environments considers beyond-the-classroom knowledge as not only valuable contributors to who students are in the classroom, but also as integral expertise informing how students can contribute through writing, participation, and discussion as part of a learning community. In learning environments such as these, according to Eli Tucker-Raymond et al., “knowledge is spread across individuals, groups, and tools, creating distributed systems of expertise” (2). Distributed expertise considers how individuals and groups craft expertise from a variety of identities, knowledge sources, cultures, and experiences. It additionally considers how groups can benefit from mobilizing existing expertise in new forms within distributed, decentered systems. Research has shown classroom environments that nurture distributed expertise help students develop confidence and authority about their own varied forms of expertise (see Langer-Osuna and Engle) and even help them to learn from and with one another (see Cassidy et al., 19). Distributed expertise further defines expertise to be plural, positional, situated, non-hierarchical, and culturally empowering. Furthermore, it recognizes that expertise is connected to power structures and that ideals of distributed expertise must be continually pursued and worked toward if they are to be effective and equitable.

While composition scholars such as Meridith Reed have pointed out how cultural and personal experiences can supplement disciplinary expertise in the training of composition instructors, the pedagogical approach outlined here strives to do similar work for composition students by infusing the classroom with opportunities for enactment of distributed expertise within the confines of the writing classroom using social media as a learning and connection tool. This article offers instructors an approach to nurturing distributed expertise in their writing and composition classrooms that takes advantage of the communication, sharing, and connection affordances of social media environments. In my classroom, I use the social media platform Slack to help students write, share, connect, and compose for one another. Partly as a response to the growing ubiquity of social media and partly out of necessities arising from the COVID-19 pandemic, I developed a social media pedagogy using Slack that helped students to learn from and alongside one another through weekly composition and connection on the platform. I made incremental changes to the pedagogy each semester that I used Slack and grew fascinated with the insights students were collaboratively generating, the connections they were uncovering, and the knowledge they were producing together as they shared, interacted, and exchanged comments with one another each week.

In an effort to more firmly develop my participatory and interactive social media pedagogy, I conducted an IRB-approved qualitative case study with grounded theory elements that examined what learning was occurring in the social media environment, how that learning was occurring, and how this knowledge could inform composition instructors’ understanding of social media’s utility in their First Year Composition courses. After collecting, coding, and analyzing Slack participation data, student reflective journal entries, and interview data with participating students, the study generated a variety of categories that comprise its findings. One of those categories, distributed expertise, offers insight into the utility of social media pedagogies in composition classrooms and beyond to support learning environments in which expertise is distributed, situated, plural, positional, and valued.

In this article, I highlight a social media pedagogy design that supports distributed expertise in a First Year Composition classroom learning community before examining data that demonstrates how social media pedagogies can help nurture environments of distributed expertise. The article then closes by offering instructors in composition and beyond some “best practices” for supporting distributed expertise in their social media pedagogies. As a classroom practice, supporting distributed expertise has important potential related to diversifying classroom knowledge forms, enacting social justice, and supporting student social learning that instructors across the curriculum can benefit from.

Using Slack in Composition Pedagogy

To nurture digital education environments capable of enabling and encouraging distributed expertise and other important learning practices, I’ve developed a social media pedagogy for both in-person and online courses that draws on a rapidly expanding literature that connects social media technologies and learning in composition classrooms. Scholar-practitioners in composition and rhetoric studies have developed an array of approaches to productively using social media tools to augment their pedagogies (Daer and Potts; Walls and Vie; Witek and Grettano; Shepherd; Buck; Faris; Gallagher; Richter, Network-Emergent; Johnson and Salter). For instance, Stephanie Vie has written extensively on how social media pedagogies can help students to develop outcomes such as “critical digital literacies” and social media writing abilities, arguing that composition scholar-teachers must pay attention to changes brought about by social networks and participatory culture (9). Lilian Mina has connected social media pedagogical applications with development of critical literacies among students (272) and still others have suggested that reflecting on Facebook composing as part of a composition course can help to sustain attention to rhetorical choices, voice, and persona across multiple composing situations (Amicucci 36; see also Amicucci, Experimenting with Writing Identities on Facebook through Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity). As part of their special issue of Computers and Composition on Web 2.0 and Composition, Day et al. consider how social media can help compositionists to “collaborate, compose, and innovate on the Web and in the classroom,” but also call attention to the need to “move beyond conceptions” of social media use in classrooms that are “purely technological” (1-2). Finally, Savanna Conner and Patricia Webb call attention to how networked technologies like social media have “potential for expanding the boundaries of the traditional classroom” and “enable productive interactions between stakeholders…inside and beyond the writing classroom” (1).

Composition scholar-practitioners have helped to establish goals, classroom practices, and pedagogical values for social media use in classrooms that have helped students in both in-person and online courses to write for various audiences, engage new genres and composing situations, and expand their digital literacy practices with social media. In many ways, this article’s pedagogy and argument draw together some of the goals and orientations toward technology use provided by composition scholar-practitioners and aim them toward a Slack digital learning community that elevates distributing expertise as a core pillar of educational practice. Concerning learning environments that prioritize distributing expertise among a multitude of participants, Mimi Ito et al. point out that “creating a program or environment where authority is shared and expertise is distributed, allowing for a broad range of ways to participate, only matters if there are also visible ways… to share and exchange expertise and discover resources” (78). In this perspective, distributed expertise arises in social situations such as learning communities when effective and valued participation is defined in part by participants themselves and when they feel empowered to share, interact, collaborate, and create in forms that they personally find generative. Ito et al. argue that all involved stakeholders should have “opportunities to take leadership and contribute in diverse ways to the shared endeavor,” adding that “all participants should have a stake in and have influence over the project, regardless of age and expertise… norms and expectations are collectively maintained” (75). In other words, distributed expertise can arise when social interaction occurs on participants’ own terms, with their individual goals, choices, interests, and curiosities being valued parts of the social dynamic.

The approach that I developed for using Slack as a social media tool in my composition and professional writing pedagogies builds on and harmonizes some of these existing approaches. This pedagogy focuses less on social media technology than on the participatory, interactive, and social actions that students can engage in when composing for and with their peers in rhetorical environments shaped by the affordances of social media tools. In other words, pedagogy is where learning through social interaction and participation occurs, with social media tools serving as an avenue to assist students in enacting these participatory social learning practices. Drawing inspiration from Henry Jenkins’ idea of participatory culture as well as Sarah Arroyo’s repurposed development of participatory composition based partly on Jenkins’ ideas, this pedagogy asks students to design their own composition for the Slack community each week that engages course content and classroom goals entirely on students’ own terms and in their individually chosen participation form. As Tucker-Raymond et al. write, “participatory pedagogies encourage reliance on distributed expertise because responsibility for knowledge resides with all participants… since the locus of authority in the classroom shifts away from the teacher” (2). In this way, student participation in the digital learning space helps to build an environment in which expertise is distributed among many involved classroom stakeholders.

Each week, students participate by composing for the classroom learning community in the Slack channel, but how they participate is up to them. Students write eight sentences (or the equivalent in multimedia formats including the recording of short videos, creating memes, attaching images, and sharing internet links) engaging one of what I call “Modes of Participation” (see Appendix). The modes of participation, which include #Share, #Teach, #Crowdsource, #Expand, #Make, #Moderate, #Link, #Meme, and a variety of others, mimic practices and logics organic to social media environments with an orientation toward social learning and toward enacting course goals through participation. After composing their 8-sentence contribution engaging one of the “Modes of Participation” that aim social media logics toward social learning, students end their Slack post with a question for the learning community. Students are free to create their own “Modes of Participation” as well and are encouraged to reinterpret existing participation modes in their own way. After posting their participation contribution and question in the Slack channel, students then respond to two questions on other students’ posts and reply to two comments on their own post (assuming there are comments for them to respond to).

The “Modes of Participation” that students engaged each week allowed them to collaborative craft connections, generate insights, and share knowledge in the Slack classroom learning community. While a full list of the “Modes of Participation” appears in the Appendix, a partial list includes:

#Share: Share an experience of yours that relates in some way to the course content, readings, discussions, assignments, or activities for the week. How can your personal, individual experience inform the course concepts this week? How can your perspective, culture, or background influence how we as a class collectively understand ideas, rhetoric, writing, or society?

#Teach: Explain an important concept, idea, term, phenomenon, or perspective to your classmates. What is most important about this term, idea, or concept? What should students in Composition & Rhetoric know about it or focus on? What’s pertinent for our course? What might an average person now know or understand about it?

#Crowdsource: Have a question on an assignment? Crowdsource an answer from your peers. Unsure about a course concept or what a term means? Crowdsource an answer from your peers. Curious about what your peers think of some news story, phenomenon, event, or shared experience? You get the idea.

#TellAStory: Share a story from your personal experience that is relevant to something discussed in class, in a reading, in an assignment, or that is related to writing/rhetoric in some way.

#Meme: Use ImgFlip.com/MemeGenerator to create a meme that explains, explores, engages, or remediates some concept or phenomenon from the course. *Stay appropriate- no memes that reinforce problematic perspectives* Then, in four or five sentences, explain the meme’s premise, lesson, and main ideas to the class. What does it convey? What is it trying to say?

#Connect: What two or more ideas have you come into contact with, either in this course or in this conversation on Slack, that you can connect to something we haven’t discussed yet in this Slack space?

As an instructor, I encourage students to avoid selecting the same participation mode two weeks in a row, encouraging them to branch out and participate in new ways. A typical student’s week of Slack participation might begin by selecting a “Mode of Participation.” If the student chooses #Connect, they might consider connections between two or more course concepts (such as considering connections between pre-writing and revision or ethos and visual rhetoric), explain that connection and its importance to the learning community in an eight-sentence Slack post, then close out with a question for their classmates such as What magazine covers or television commercials come to mind for you when considering connections between ethos and visual rhetoric? The student would then comment on two other students’ posts, potentially responding to those students’ questions and monitoring their own posts for comments, responding to at least two of them. This process represents an ongoing social media pedagogy that is replicated each week for the duration of the semester.

I chose Slack as the pedagogy’s platform for a few key reasons. As Emily K. Johnson and Anastasia Salter note, in online or hybrid pedagogies, “design elements and platform affordances can offer significant potential impact on the classroom” (3). This is especially true of platforms and their interfaces, which Jennifer Sano-Franchini argues support “technologically mediated social interactions” that can “materially re-shape how users connect and relate with one another” (1). As a platform that is free for educational users, Slack allows students to write and connect with one another without necessitating either an expensive LMS system or the purchase of expensive software. Commonly marketed as a platform intended for both small and large businesses, Slack channels help users to form enclosed networks that are private, non-public, and free from unwelcome guests. With users ranging from Target, NASA, Uber, and The New York Times to small businesses and a variety of universities, the platform markets itself around values of teamwide collaboration, mobile adaptability, flexible workflows, and integration with other platforms (Slack, Made for People). Slack also is a platform that makes intentional institutional efforts to be as accessible as possible, striving to adapt to meet the needs of users with disabilities (see Accessibility in Slack). Stephanie Vie writes that “digital multimodal technologies such as social media have the potential to offer greater inclusion to people with disabilities… at the same time, though, technologies required for students’ use in online education must be accessible to all, including students with disabilities” (62). In Jennifer Sano-Franchini et al.’s parlance, Slack generally can support “pedagogical community building and accessibility” (1). Slack is screen reader compatible and as a platform, company, and technology sustains ongoing commitments to designing for accessibility. Slack also maintains mobile smartphone and tablet applications, which many students make extensive use of in addition to more conventional laptop-based use (several students reported connecting with classmates on Slack while on the bus or while walking back from class).

While I used Slack for this pedagogy, other platforms like Discord, Yellowdig, Facebook Groups, and Google Classroom also enable similar practices and social connections for social media pedagogies. Discord in particular has been a popular choice for instructors to use in their classrooms, especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, as many students are already familiar with its logics and supported practices. However, Discord’s cultural associations as a gaming platform carry baggage related to misogyny and digital aggression, complicating the platform’s use in the classroom (Johnson and Salter). Slack’s cultural associations as a platform frequently used for business purposes risk some similar concerns, though likely to a lesser degree. In terms of technological capacities and affordances, Slack and Discord have few major differences, as each allows for the sharing, interaction, direct participation, and social media-organic practices that can be leveraged for social learning. Thus, I made an informed choice to use Slack based on the platform’s general utility to support meaningful social interactions, its prioritization of mobility and accessibility, and its frequent use in professional workplaces that students can benefit from in internships and professional life.

Overall, Slack’s comment threading, channel organization, accessibility values, and lack of cost made it the best choice for the social media pedagogy examined here. In many ways, the pedagogy described here can work across platforms, as focusing on supporting meaningful social interactions and leveraging rhetorical practices organic to social media likely is more impactful on students’ learning experiences than choosing any one platform over another. In other words, learning how to #Teach, #Link, #Transfer, or #Collaborate across platforms is likely more beneficial for students compared to simply learning how to use any individual platform.

Methods

After designing, revising, and teaching this social media pedagogy over the course of multiple semesters of First Year Composition, I set out to determine what students were learning through the Slack pedagogy and how that learning was occurring. I designed an IRB-approved qualitative case study with grounded theory elements that collected data about Slack participation from student participants enrolled in two of my composition courses.

Working with a modified grounded theory qualitative approach (see Glaser and Strauss as well as Charmaz), the study investigated the primary research question, How do student composers invent within networked social media environments? The study included the secondary research question, What can this study tell us about potential ‘best practices’ for social media pedagogies?. The study collected, coded, and analyzed data from three sources: 146 pages of Slack participation data provided by student participants writing in the classroom Slack channel, 139 pages of student reflective journal entries reflecting on their experiences participating in Slack, and 111 pages collected from nine interviews that I conducted with participating students. All of the study’s 22 participants were enrolled in my in-person composition courses at an R1 research university in the American southeast during the 2021-2022 academic year. Throughout the duration of the study, I engaged in theoretical sampling, iterative and reflexive coding (open, focused, theoretical), and an extensive process of memoing in-line with grounded theory approaches. I began the study with four a priori conceptual categories, one of which was distributed expertise. These a priori conceptual categories were categories that I knew I wanted to investigate and learn more about from previous experience with the pedagogy. I identified these a priori conceptual categories at the beginning of the study and the data that supports them comprises some of the findings of the study (see Table 1). Though I began the study knowing I wanted to investigate the a priori categories, I remained continually open to their revision and evolution based on codes and data.

At the beginning of the semester, I introduced Slack social media pedagogy to students in two First-Year Composition courses. About two weeks into the course, I introduced this qualitative study to students and explained its goals, research questions, data collection and analysis processes, and their potential role as participants in the study. I also presented students with an IRB-approved informed consent document informed heavily by the Conference on College Composition and Communication’s CCCC Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Research in Composition Studies statement.

Data was collected in the study through the aforementioned Slack participation data as well as two rounds of Slack reflective journal entry submissions and nine interviews that I conducted with student participants. I collected and coded all the Slack participation data across 16 weeks of the course from consenting students, including original posts as well as comments that involved social interactions between two or more participating students. For each of the 16 weeks of the study, in roughly two-week increments, I reviewed and extracted participating students’ Slack posts and comments into text files that were then uploaded into Dedoose and coded.

I also collected and coded two iterations of student reflective journal entries for each participating student, with one entry being submitted roughly six weeks into the semester and the other being submitted roughly 15 weeks into the semester. These three- to four-page reflections on Slack participation were a normal part of the course that I only collected for coding from participating students. These reflective journal entries asked students to reflect on their social learning practices in Slack. Illustrative questions included: What sorts of emotions did you feel as you wrote and conversed with others in the networked discussion?; Did you learn anything through sharing stories, experiences, responses, or reactions in Slack with your peers? Similar questions asked students to reflect on building social relationships with classmates, on learning from and with others through listening, and on the social dynamics of the Slack learning community.

I then conducted nine interviews near the end of the semester with consenting students. Each interview was conducted on Zoom and lasted about 30 minutes. Interviews consisted of students answering questions concerning their participation on Slack, what their social interactions there looked like, and how they felt they learned or did not learn when interacting with others in the digital learning community. The interview questions that I asked students were largely similar to those that I asked them in their Slack reflective journals, but interviews additionally were a great opportunity to engage in theoretical sampling and to achieve saturation in codes and categories. In short, interviews served as an opportunity for me to ask students to expand on what they had written in previously collected data and to draw connections between different codes. The interviews with participating students served as a vital chance for theoretical sampling, helping me to connect codes together and explore their relationships as a category developed.

In total, I collected and coded over 396 pages of data that helped to inform the findings of the study. While the data was being collected, I engaged in extensive memoing and coding in the qualitative software platform Dedoose. The study ended up generating data supporting six categories, one of which was distributed expertise.

Distributed Expertise on Slack

My implementation of the social media pedagogy on Slack proved capable of cultivating distributed expertise among students. The findings of this qualitative case study exhibit distributed expertise that appears within the learning community characterized by attention to positional insight, discussion across difference, transferring prior knowledge, resource sharing, and social interaction, among other learning activities. From the beginning, codes relating to distributed expertise appeared in the student-produced data in this study, especially in the Slack participation and reflective journal entry forms of data collection. I define distributed expertise as characterizing an environment in which expertise is plural, positional, situated, non-hierarchical, and culturally empowering. As the findings of this case study illustrate, social media learning communities have the potential to encourage learning through distributed expertise in practices of sharing positional insight, having discussions across difference, transferring prior knowledge to new situations, resource sharing, and social interaction, among other practices (see Table 1).

Connecting Rhetoric to Personal Experience |

Citing Positional Expertise |

Agonism |

Connecting Course Content to Personal Experience |

Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence |

Connecting Rhetoric to Personal Experience |

Pop Culture References as Evidence |

Transferring Previous Knowledge into Writing/ Rhetoric Insight |

Statement of Identity |

Teaching Someone |

Understanding/ Summarizing Readings |

Reflecting on Social Learning or Learning From/With Others |

Reflecting on Listening To/Learning From Someone Else |

Commenting on Critical Reading of Others’ Ideas |

Commenting on Discussions Across Difference |

Critical Sharing of an Internet Link |

Discussing Building Relationships with Classmates |

Seeking Help/Assistance/Advice |

Providing Internet Link as Evidence |

Analyzing/Exploring a Disagreement |

Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence

One of the more prominent codes that emerged in the data that connects distributed expertise with the social media learning environment is the “Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence” code. The “Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence” code showcases the willingness of students participating in the Slack social media network to broaden their horizons of what evidence is and can be to include personal experience, reflections on past situations, and on positional expertise. Stories are always rhetorical and can help others build empathy and sympathy for a situation, cause, or organization. They can also be a good way to advocate for a belief or passion and can be used to explain and justify particular points of view, perspectives, or ways of understanding events. As such, the “Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence” code commonly appeared in situations where students were discussing some larger social, cultural, or political phenomenon and decided to contextualize it within their own experiences. It often appeared alongside similar codes such as “Connecting Course Content to Personal Experience” and “Connecting Rhetoric to Personal Experience,” demonstrating the ways the social media learning community helped to connect personal experiences with larger social, political, or cultural issues that were the topic of course discussion.

Considering this, storytelling and references to personal experience commonly functioned as evidence for some larger point and worked to help explain both why someone believes how they do about an issue and why they feel that way. Stories arising from experiences also helped students to form social bonds and learn from one another, as one student commented, “Without Slack, I never would have heard these people’s stories.” Stories from personal experience served to translate perspectives and points of view between students, and they helped to not only form social bonds and reciprocal learning relationships, but also helped others explore new ideas, encourage alternative modes of thinking, and broaden what others within the learning space knew, understood, or appreciate about a particular situation. Storytelling and personal experience being used as evidence to highlight or illustrate an argument showcases the plural, situated, and culturally empowering forms of expertise that contribute to environments where distributed expertise is enacted by students.

Teaching Someone

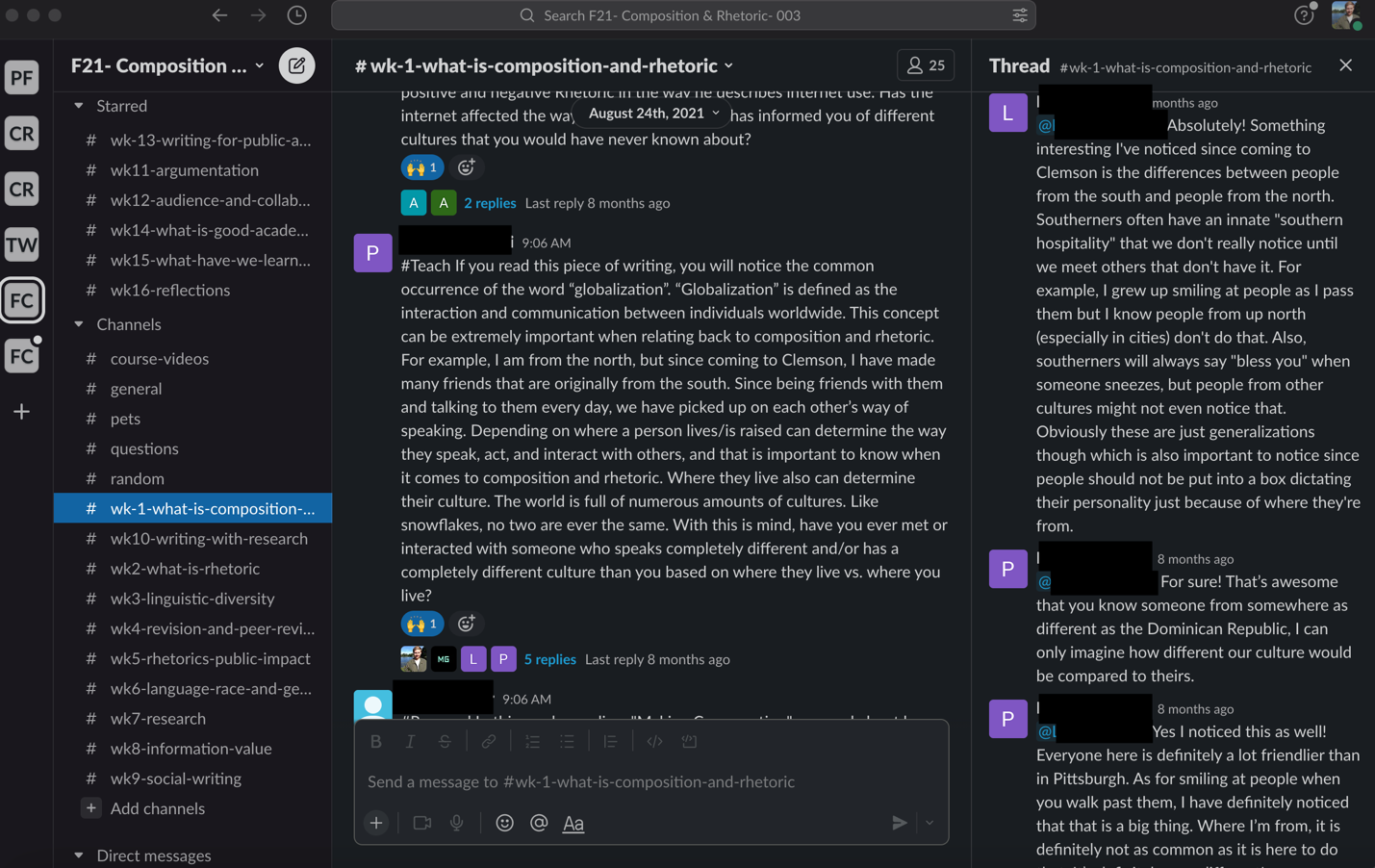

The “Teaching Someone” code also emerged frequently. Students commonly engaged in practices of teaching others, explaining ideas, unpacking concepts, filling in important details, addressing gaps in understanding, and providing important context, background, or frame of reference. In many cases, students used the #Teach mode of participation to proactively teach other members of the learning community about yet unexplored aspects of course content or about specialized knowledge they’re privy to, such as when one student informed others about the research they’d performed regarding dictionary definitions of key terms in a course reading (see Figure 1). When students used the #Teach mode of participation, they engaged in both learning ecology formation and distributed expertise, which frequently worked together synergistically in this learning space. In using #Teach, students recalled prior knowledge to communicate important knowledge, context, detail, or background to others who might benefit from that added communication. These actions of distributed expertise, where students mobilize their own expertise in the form of pre-existing or recently obtained knowledge, function as a core opportunity for students to learn socially by transmitting information, making connections, translating private perspectives into public statements, and addressing gaps or concerns in the course conversation that they’re uniquely equipped to consider.

Figure 1. A student uses the #Teach mode of participation to offer insights to others about globalism, cosmopolitanism, and the meaning of specialized vocabulary arising in a shared course reading.

In other cases, students used modes of participation beyond #Teach but engaged in some of the same teaching practices in slightly less formal ways. For instance, students commonly used #Share as an opportunity to share an experience or insight that they’ve had, but then also engaged in translation work to teach the learning community about what the experience or insight they’re sharing means for culture, society, politics, rhetoric, or writing. Other times, practices related to teaching actions occurred in comments when students would either comment on someone else’s post with a teaching insight or when they would be pressed on their ideas expressed in a post and need to explain, contextualize, qualify, and reanalyze elements of what they’d originally written. As a learning activity, teaching others forces a student to conceptualize their ideas in language, then explain those ideas in ways that others can appreciate and identify with, and then translate the idea’s relevancy, applicability, value, and contribution to the wider learning community. As such, teaching others is a valuable way that distributed expertise is enacted in social media pedagogy. Giving students an opportunity to be experts of their own experience and of their own perspectives (and actively valuing that expertise) offers avenues for learning community enrichment through the sharing of unique perspectives, solicitation of a plurality of voices, and broadening of the context details that can enhance a discussion. One student wrote that “Slack has also caused me to think about other perspectives and make me appreciate what I have in the world,” showcasing how the social learning activity encourages practices of self-reflection, metacognition, idea comparison, and synthesis of conflicting perspectives. Broadly speaking, students teaching others demonstrates distributed expertise that is non-hierarchical, positional, and even culturally empowering in some cases.

Positional Expertise

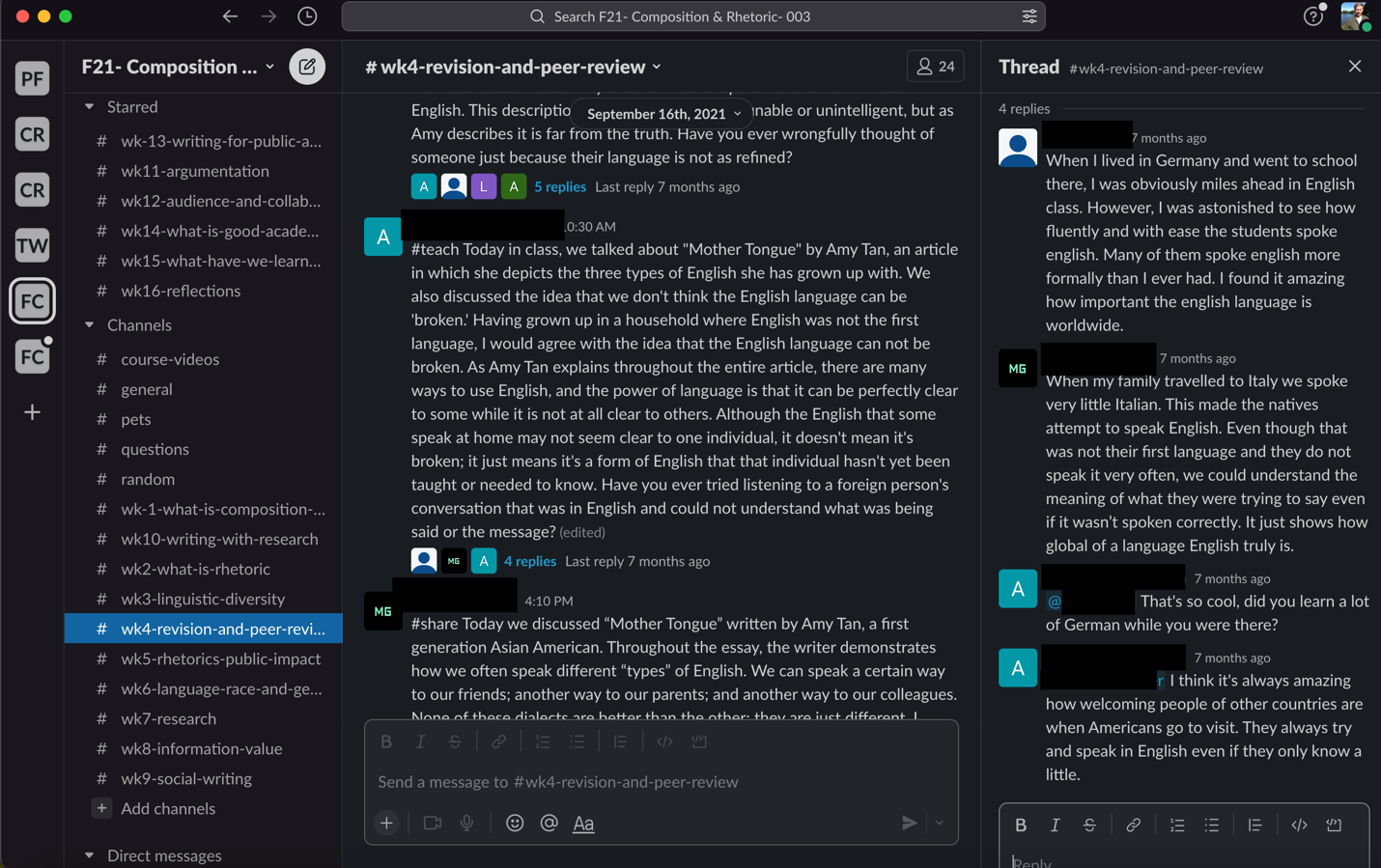

Other codes emerging in the data that inform how instructors can understand distributed expertise and its relationships to individual and group identity are “Citing Positional Expertise,” “Statement of Identity,” “Commenting on Discussions Across Difference,” and “Commenting on Critical Reading of Others’ Ideas.” One of the important codes that emerged in this study is “Citing Positional Expertise,” as this code gestures toward social justice opportunities that the social media pedagogy can offer to instructors and students alike. For instance, Figure 2 showcases an interaction in the Slack learning community involving a student leveraging their experiences as someone who grew up in a home where English was not the first language to discuss linguistic justice, cultural hybridity, and social justice. Research from Ann Amicucci has shown that social media writers engage in “nuanced rhetorical experiments” to enact but also develop their “writing identities,” which certainly occurred in our classroom Slack learning community (Experimenting with Writing Identities 1). When citing positional expertise, students complicated understandings of discussion topics by citing how their positional bearing within society, especially relating to race, gender, disability, sexuality, and class, helped them to form certain opinions, perspectives, understandings, and views on the world. By considering how positional experience impacts how a person feels, thinks, and believes about the world or about society, students were able to not only engage in moments of reflection about identities and ideas but also to consider the impact their ideas and beliefs can have on others.

Figure 2. Leveraging their status as someone who grew up in a household where English was not the first language, a student shares insight into linguistic diversity, cultural hybridity, and social justice, to which others add on with similar experiences.

Examining positional expertise also provided students an opportunity to share how their positionality provides them unique, privileged, personal access to some of the pertinent affective knowledge needed to truly understand sensitive issues. Many topics, like race-based police violence, anti-transgender hate, or sexual harassment on college campuses benefit when the voices of victims and survivors are foregrounded. Because these problems can disproportionately impact people already marginalized in society, citing positional expertise can be one way that experience can inform how we approach important topics (at an individual’s discretion and on their own terms). Citing positional expertise allows for a blending of the personal and the social to inform group discussion and allows space for marginalized viewpoints (especially related to race, gender, disability, sexuality, and class) to be not only prioritized and foregrounded, but also actively valued and critically considered by the learning community. In the classroom Slack learning community, the citing of positional expertise encouraged students to think beyond their individual perspectives and to critically reflect on how their privileges, marginalization (or lack thereof), advantages, and positional vantage points influence the ideologies they bring to the world. In other words, examining positional expertise helps students to consider what and why they believe what they do, who those ideas serve or neglect, and what these beliefs say about their relationships with others who are different from them. As such, citing positional expertise represents a viable opportunity to enact goals of both distributed expertise and social juice in a digital learning classroom, especially by encouraging actions that reflect positional, pluralistic, and culturally empowering elements of distributed expertise.

Discussions Across Difference

Students also participated in discussions across difference, engaging in disagreements about interpretations, course material, politics, and current events. As exemplified by the “Commenting on Discussions Across Difference” code, participants in some cases articulated beliefs, shared them with unresponsive audiences, and still found a way to discuss the common topic in ways that were healthy, mutually beneficial, and without aggression. In an interview, one student said that in the Slack conversation, “everybody gets an equal voice.” In many cases, discussions across difference related to differences in personal preferences, contrasts in individual choices, and divergent but not mutually incompatible interpretations of course readings or content. In other cases, outright political differences arose in conversation, with students either not continuing the conversation or doing so in a way that was mutually beneficial, polite, and full of listening, generally characterized by thoughtful articulation of ideas to a good-willed audience that, while unconvinced, was not disrespectful or dismissive, either. Social learning pedagogies generally do not (and should not) shy away from discussion of politics, culture, or society, and facilitating discussions across difference is one way to ensure these meaningful learning opportunities are respectful, healthy, and symbiotic (see Richter, Writing with Reddiquette). In these cases, generative difference can be approached in a way that can be beneficial for all involved parties (though this kind of generative disagreement is hardly always the case). Listening to the ideas, perspectives, and opinions of others was commonly reported as a learning opportunity by students, showcasing how a social media pedagogy offers avenues for learning through horizontal student-to-student bonds. One student reported in a reflective journal entry:

“The benefit to the scholarly feel of Slack is that it causes me to think about the deeper meaning of whatever I am writing about. It also gives me a greater appreciation for the insight of others and their thoughts on a subject. It helps me to think more critically about what my peers post and what my responses are. Often some of my more interesting ideas come from responding to someone else’s post. Responding to what someone else said requires me to think more in depth about what they said, and how it relates to the topic they are discussing. When I then respond, I then have a new perspective, not only on what their point is, but also on the original topic.”

In this case, social interactions involved listening to divergent perspectives, considering preconceived ideas and differences in opinion, then comparing and possibly synthesizing these differences together in a way that involves critical analysis, intertextual writing, and learning from another student. Leveraging discussions across difference for educational benefit reflects the situated and plural nature of distributed expertise in classroom learning environments.

Social Learning and Seeking Assistance

Distributed expertise also took different forms that were productive for learning. From a practical standpoint, distributed expertise appeared quite directly and literally when students helped one another to complete assignments, address writing challenges, and overcome course difficulties, all of which appeared as the “Seeking Help/Assistance/Advice” code. The “Reflecting on Social Learning or Learning From/With Others” code demonstrates how students not only engaged in practices of learning from what other people have said or written but also reflected on that process and on how it happened and what it meant to them. In this case, distributed expertise works both through communicating expertise to others as well as recognizing expertise others have that another student might not have, especially due to experiences related to race, gender, sexuality, disability, or class. Distributed expertise also was enacted in generative ways when students critically shared internet links as evidence or context to inform the discussions they partook in as well as when students understood or summarized readings, as their interpretations shared in the Slack channel were oftentimes plural, diverse, divergent, and different, opening pathways for generative comparison and contrast. Additionally, distributed expertise also was enacted productively when students discussed building relationships with classmates, when they engaged in a thoughtful disagreement, when they used pop culture references as evidence, and when they transferred previous knowledge into a writing or rhetoric insight. Considering this, social learning and seeking of assistance from other students showcase the situated, non-hierarchical, and pluralistic possibilities that social media pedagogies are capable of nurturing that result in expertise becoming distributed.

A few other quotations from students demonstrate larger activities related to distributed expertise that appeared in this study. First, students commented several times that they appreciated learning from the unique stories and insights of others. This includes one student who wrote:

“Through Slack, I learned about their perspective on discussions that were had in class that day and about the ways in which they understood the topics relevant to our class. I feel that learning this information about my classmates was beneficial to the learning process, as discussing how others processed the information we were given made me consider it through different perspectives. It required me to think critically about my own perspective, and change it based on new information which I was presented with. On top of this, I learned some interesting stories from my classmates through this channel.”

Other students reported that the social network helped to give them a voice in class that they may not have had otherwise:

“Slack has been a huge help in being able to communicate with my classmates. I generally am a pretty quiet person in class and have a hard time sharing my ideas, so being able to share online has helped me meet my other peers without the pressure of talking in front of everyone. I felt lots of emotions when I wrote to others in Slack. There were feelings of growth and positivity.”

Finally, students commented time and time again how interacting with others online helped them to grow as writers, communicators, and rhetors:

“After composing my Slack post, I typically enjoy reading all other outstanding posts created by other classmates. I enjoy seeing which classmates shared similar ideas and posts and which classmates may offer a different point of view. Over the past few weeks, reviewing these slack posts from other classmates has proven to be very helpful in the sense of learning how to do research, write a persuasive and argumentative essay, cite sources, and recognize the importance of different languages and interpretations. These new ideas and different points of view all made it easier to learn how to work on the out of class assignments… This learning environment that is shared between my classmates and I is perfect for us to help not only each other, but also ourselves.”

In summary, the findings of this study show how distributed expertise can be generative for learning in social media environments through the facilitation of sharing positional insights, discussion across difference, the transferring of prior knowledge, resource sharing, and symbiotic social interaction. One student reported that “as a writer, Slack has helped me become more confident inside and outside the classroom and has helped teach me that my perspective, voice, and opinion matter and can be beneficial to others.” Helping students to more fully realize the importance, value, and significance of their perspectives on the world benefits any classroom, and as we’ve seen, social media pedagogies can encourage students to gain confidence in their ideas, writing, and ability to impact others beneficially through distributed expertise.

“Best Practices” for Nurturing Distributed Expertise with Social Media

The utility of social media pedagogies to nurture distributed expertise in classroom learning environments can help students across the curriculum to learn through storytelling, teaching others, sharing positional knowledge, crowdsourcing requests for help, and through a variety of other expertise-sharing and expertise-building practices. How can instructors maximize the learning and connection arising from environments of distributed expertise, though? The findings of this study inspire three “best practices” for instructors to consider to most effectively nurture distributed expertise in their social media pedagogies. To maximize learning through encouraging distributed expertise, instructors should define and discuss positional expertise, crowdsource requests for help or assistance, and explore disagreements as they arise in their social media pedagogies.

Best Practice: Define & Discuss Positional Expertise

To start, instructors should provide students with definitions of what distributed expertise is. Additionally, instructors should examine specific examples and moments in which distributed expertise is demonstrated, pointing students toward concrete situations in which expertise on a topic strays from conventional norms and assumptions. By highlighting how expertise and insight into a phenomenon can be gained through personal experience, story sharing, and positional insight, in addition to expertise obtained in more conventional forms such as formal qualifications or research, instructors can broaden what sorts of insights, commentary, knowledge, and know-how are valued in their classrooms. Actions highlighting distributed expertise can also help to increase student confidence in the value of their ideas, in the relevance of their experiences to inform discussions of important issues, and in the forms of knowledge that are elevated by the pedagogy. Inspired by codes in the data like “Connecting Rhetoric to Personal Experience,” “Citing Positional Expertise,” “Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence,” and “Statement of Identity,” defining and discussing distributed expertise helps students to intentionally enact these helpful and equitable practices.

In this sense, discussing and prioritizing distributed expertise in a social media pedagogy offers an opportunity to enact social justice in the learning space, as valuing expertise based on positional insights and knowledge— especially related to race, gender, disability, sexuality, and class— can broaden what knowledge, stories, and insights are valued by the classroom learning structure, potentially subverting dominant systems of power in momentary but important ways. Encouraging the enactment of distributed expertise also allows students to bring their unique cultures, backgrounds, ethnicities, and interests into the classroom, as signaling to students that expertise and knowledge unique to a particular cultural group is valued helps to create environments that are more inclusive and hospitable for the sharing of cultural knowledge. Sharing of cultural knowledge, individual experiences, and community values with a digital learning community can result in moments of vulnerability for students. Actively encouraging distributed expertise is one way instructors can help to lessen this vulnerability and encourage productive attitudes toward these practices, helping to enact practices of social justice in the classroom.

Best Practice: Crowdsource Requests for Help or Assistance

Inspired by codes such as “Seeking Help/Assistance/Advice,” “Teaching Someone,” “Understanding/Summarizing Readings,” “Reflecting on Social Learning or Learning From/With Others,” “Reflecting on Listening To/Learning From Someone Else,” and “Commenting on Critical Reading of Others’ Ideas,” instructors should also crowdsource requests from students for help or assistance that arise in the social media environment. For instance, if a student in a writing course solicits feedback from classmates regarding the effectiveness of their introduction paragraph, instructors should bring introduction paragraphs up in class or revisit them in other course materials once again. Instructors should notice these moments as they occur in the social learning environment and then bring them up either verbally in an in-person course or in other course materials in an online class setup. If one student is facing a specific difficulty, problem, or challenge, there’s a fair chance that other students are encountering and navigating a similar challenge. Considering this, crowdsourcing and discussing requests for help, assistance, or advice can help to inspire learning moments for other students in the course who may be facing similar challenges, offering avenues in which one student’s expertise can be of help to others.

Crowdsourcing requests for help or assistance helps to enact distributed expertise because it helps students to form horizontal student-student bonds as well as helping students to value their own insights, perspectives, and knowledge as beneficial to the larger learning community. An important opportunity for instructors to nurture and encourage social learning is to discuss what it means to learn from classmates online and ask students to verbally share stories of their experiences learning from or alongside others in the digital learning environment. Pointing out fruitful moments of social learning can help students to note the benefits of these learning interactions and can additionally help students to enact these processes in future interactions. Highlighting successful social learning interactions as they occur in the social learning environment can help students reflect on those interactions, notice what approaches and attitudes made them fruitful, and replicate those methods in future interactions. It also has potential to help students be more successful in the course, contributing toward broader social justice possibilities.

Best Practice: Analyze & Explore Disagreements

As disagreements arise in the social learning environment, discussing disagreement as a common occurrence as well as in specific practice can be a valuable learning moment for students. Disagreement encourages students to put their thoughts into words, consider how best to communicate ideas to potentially disagreeable audiences, explain components or details of their ideas when responding to comments, and synthesize conflicting perspectives together based on social interactions with peers. As many participants in this study mentioned, disagreement can be a productive and generative moment if handled in a way that respects all members of the discussion and is grounded in mutual respect. Stemming from codes such as “Analyzing/Exploring a Disagreement,” “Commenting on Discussions Across Difference,” “Discussing Building Relationships with Classmates,” and “Agonism,” instructors should consider analyzing and exploring disagreements with their students. One student wrote “when composing posts and replying to others I also learned things from my classmates… I learned how to respectfully communicate with them over slack, even if I disagreed with them” [sic]. Another student wrote “[W]hile some people do not like when others disagree with them, I actually don’t mind it… I find it very interesting to see other people’s viewpoints, especially if they are different from mine… Slack is a great tool to use for this purpose; it has allowed us to connect with others through similar views, and even different views.” Considering these reflections, communication across disagreement is a valuable rhetorical aptitude for students to develop. Instructors can consider analyzing and exploring disagreement verbally and explicitly as an opportunity to nurture distributed expertise, discussing with students how differing viewpoints can be beneficial and generative if grounded in mutual respect and kindness.

An effective way to analyze and explore disagreements is to value how storytelling and personal experience can be approached as evidence to inform how the learning community conceptualizes and understands an idea or concept. Instructors can help the learning community to value storytelling and personal experience as evidence to encourage distributed expertise, and in doing so can help to make disagreements more generative for everyone involved. In making stories from experience and individual practice valued parts of the classroom, instructors not only signal to students that their cultures, backgrounds, perspectives, and values are respected in the course discussion but also that they are important sites of knowledge that can inform classroom discussion on any particular topic. Stories help to orient humans and their cultures and elevating personal experiences and storytelling helps to nurture distributed expertise in ways that can supplement more traditional forms of expertise, such as expertise obtained through research or prior college coursework. Elevating stories and personal experiences can also open up opportunities to enact social justice in the classroom by honoring and valuing a wide range of knowledge forms that eschew traditional “sage on the stage” teaching models that risk reinforcing or projecting dominant structures of power.

Conclusion: Distributed Expertise, Social Media, & Social Justice

Pursuing distributed expertise as a core classroom outcome to continually work toward and strive for can be an incredibly valuable endeavor for writing instructors and teachers across the curriculum. Understanding distributed expertise to characterize environments in which expertise is plural, positional, situated, non-hierarchical, and culturally empowering can transform classrooms and how they appreciate, value, and respect students while also allowing them a chance to bring extra-academic, traditionally neglected experiences and knowledge into the classroom on their own terms. The ability of social media pedagogies to support environments in which distributed expertise can flourish can help students and instructors alike to broaden how they understand expertise, to expand what forms of knowledge are considered legitimate and valued in the classroom, and to consider how generative interactions among invested classroom stakeholders can occur in digital channels. Environments in which expertise is distributed also extend important opportunities to enact practices of social justice in the classroom. In both in-person and online courses (including both synchronous and asynchronous course designs), many of the codes that appeared in this study—such as “Citing Positional Expertise,” “Storytelling/Personal Experience as Evidence,” “Connecting Rhetoric to Personal Experience,” and “Reflecting on Listening To/Learning From Someone Else”—can potentially support social interactions that contribute toward social justice.

For instance, in a structured but open-ended discussion environment, students are afforded an opportunity to bring their at-home, extra-academic cultures and literacies into the classroom as valued, respected parts of the academic environment. Modes of participation such as #Share, #Teach, #Expand, and #Connect provide students with an opportunity to connect course content and ideas to the cultures, hobbies, literacies, and knowledge important to them. In this way, knowledge that is traditionally neglected in academic discourse or that is not elevated as part of the course structure in the same way as the “real content” grows, over time and through repetition and culture building, into valued elements of the classroom. As Chris Anson notes, “self-sponsored, digitally mediated literate activities can provide forms of tacit learning… that mirror the learning encouraged and expected at school” (310; see also Shepherd, Digital Writing). Infusing the classroom with personal experiences, cultural knowledge, individual expertise, and collaborative insights generated through social interaction offers course stakeholders not only an opportunity to amplify marginalized knowledge but also to enact social justice in meaningful ways in the classroom. These actions are impactful in any pedagogy but especially are promising for asynchronous online classrooms where community interaction and social connection can be difficult to nurture, especially in the wake of the COVID-19 pandemic as asynchronous online courses become more and more common.

This possibility for sharing and social learning additionally offers students from marginalized or traditionally excluded backgrounds an opportunity to share their knowledge, values, and experiences with others on their own terms and with their own agency. Of course, any student can contribute to the learning community through beneficial but mostly innocuous participation forms such as reinterpreting a course reading or expanding on a particular term in course discussion. As such, no student is forced or pressured to share stories and experiences they are uncomfortable with and are encouraged to contribute to the classroom social learning community in the ways they consider most generative. However, offering avenues for enactment of distributed expertise represents a valuable and compelling opportunity for instructors to design social situations for their students characterized by broad notions of what expertise can be and how expertise can be appreciated and made actionable for a learning community.

Opportunities for enacting practices of social justice, both in terms of pedagogical design and in terms of student-to-student interactions, are not inherent to social media pedagogies. In social media pedagogies, the pedagogical culture and implementation matters to student learning and success as much as, if not more than, the technology that is used (and technologies are used in a tremendous variety of ways- see Robinson et al. and Moore et al.). Certainly, opportunities for small but meaningful social justice-related actions are possible when discussing positional expertise, when crowdsourcing requests for help, or when exploring disagreements as they arise in the social media discussion. The chance exists for instructors, however, to make efforts to nurture environments in which expertise can be distributed and in which plural, positional, situated, non-hierarchical, and culturally empowering participation can be normalized as modes of social learning. The ability of social media pedagogies to support and sustain the development of distributed expertise in writing classrooms and beyond represents a compelling opportunity for instructors to elevate traditionally neglected cultural insights, pluralize what forms of knowledge are valued in their course, and redefine what expertise is and can be in their classrooms.

Works Cited

Amicucci, Ann N. Rhetorical Choices in Facebook Discourse: Constructing Voice and Persona. Computers and Composition, vol. 44, June 2017, pp. 36–51. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2017.03.006.

Amicucci, Ann N. Experimenting with Writing Identities on Facebook through Intertextuality and Interdiscursivity. Computers and Composition, vol. 55, Mar. 2020. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2020.102545.

Anson, Chris M. Intellectual, Argumentative, and Informational Affordances of Public Forums:Potential Contributions to Academic Learning. Social Writing/Social Media: Publics, Presentations, and Pedagogies, edited by Douglas Walls and Stephanie Vie, The WAC Clearinghouse at the UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 309–30.

Arroyo, Sarah J. Participatory Composition: Video Culture, Writing, and Electracy. Southern Illinois UP, 2013.

Buck, Elisabeth H. Assessing the Efficacy of the Rhetorical Composing Situation with FYC Students as Advanced Social Media Practitioners. Kairos 19.3, May 2015, http://kairos.technorhetoric.net/19.3/praxis/buck/overview.html.

Cassidy, Michael, et al. Distributing Expertise to Integrate Computational Thinking Practices | NSTA. Science Scope, vol. 43, no. 7, 2020, https://www.nsta.org/science-scope/science-scope-march-2020/distributing-expertise-integrate-computational-thinking.

CCCC. CCCC Guidelines for the Ethical Conduct of Research in Composition Studies. Conference on College Composition and Communication, 6 June 2018. cccc.ncte.org, https://cccc.ncte.org/cccc/resources/positions/ethicalconduct.

Charmaz, Kathy. Constructing Grounded Theory. Second edition, SAGE Publications Ltd, 2014.

Conner, Savanna, and Patricia Webb. Using Networked Technologies to Connect Composition Studies’ Stakeholders. Computers and Composition, vol. 60, June 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2021.102650.

Daer, Alice R., and Liza Potts. Teaching and Learning with Social Media: Tools, Cultures, and Best Practices. Programmatic Perspectives, vol. 6, no. 2, 2014, pp. 21–40.

Day, Michael, et al. Letter from the Guest Editors. Computers and Composition, vol. 27, no. 1, Mar. 2010, pp. 1–3. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2010.01.001.

Faris, Michael J. Contextualizing Students’ Media Ideologies and Practices: An Empirical Study of Social Media Use in a Writing Class. Social Writing/Social Media: Publics, Presentations, and Pedagogies, edited by Douglas Walls and Stephanie Vie, The WAC Clearinghouse at the UP of Colorado, 2017, pp. 283–307.

Gallagher, John R. Update Culture and the Afterlife of Digital Writing. Utah State UP, 2019. https://trove.nla.gov.au/version/263941630.

Geisler, Cheryl. Academic Literacy and the Nature of Expertise: Reading, Writing, and Knowing in Academic Philosophy. Routledge, 2013. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203812174.

Glaser, Barney, and Anselm Strauss. The Discovery of Grounded Theory: Strategies for Qualitative Research. Routledge, 1999.

Glotfelter, Angela, et al. Something Invisible . . . Has Been Made Visible for Me: An Expertise-Based WAC Seminar Model Grounded in Theory and (Cross) Disciplinary Dialogue. Diverse Approaches to Teaching, Learning, and Writing Across the Curriculum: IWAC at 25, edited by Lesley Erin Bartlett et al., The WAC Clearinghouse at the UP of Colorado, 2020, pp. 167–92. https://doi.org/10.37514/PER-B.2020.0360.2.10.

Hartelius, E. Johanna. Rhetoric of Expertise. Lexington Books, 2010.

Ito, Mizuko, et al. Connected Learning: An Agenda for Research and Design. Digital Media and Learning Research Hub., 2013.

Jenkins, Henry. Convergence Culture: Where Old and New Media Collide. New York UP, 2008.

Johnson, Emily K., and Anastasia Salter. Embracing Discord? The Rhetorical Consequences of Gaming Platforms as Classrooms. Computers and Composition, vol. 65, Sept. 2022. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2022.102729.

Langer-Osuna, Jennifer, and Randi Engle. ‘I Study Features; Believe Me, I Should Know!’: The Mediational Role of Distributed Expertise in the Development of Student Authority. Learning in the Disciplines: Proceedings of the 9th International Conference of the Learning Sciences (ICLS 2010), edited by K Gomez et al., June 2010, pp. 612–19.

Moore, Jessie L., et al. Revisualizing Composition: How First-Year Writers Use Composing Technologies. Computers and Composition, vol. 39, Mar. 2016, pp. 1–13. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2015.11.001.

Reed, Meridith. Importing and Exporting across Boundaries of Expertise: Writing Pedagogy Education and Graduate Student Instructors’ Disciplinary Enculturation. Composition Forum, vol. 45, 2020, http://compositionforum.com/issue/45/pedagogy-education.php.

Richter, Jacob D. Writing With Reddiquette: Networked Agonism and Structured Deliberation in Networked Communities. Computers and Composition, vol. 59, no. 1, Mar. 2021. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2021.102627.

Richter, Jacob D. Network-Emergent Rhetorical Invention. Computers and Composition, vol. 67, no. 1, 2023. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2023.102758.

Robinson, Joy, et al. State of the Field: Teaching with Digital Tools in the Writing and Communication Classroom. Computers and Composition, vol. 54, Dec. 2019. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2019.102511.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer. Designing Outrage, Programming Discord: A Critical Interface Analysis of Facebook as a Campaign Technology. Technical Communication Online, vol. 65, no. 4, 2018. www.stc.org, https://www.stc.org/techcomm/2018/11/08/designing-outrage-programming-discord-a-critical-interface-analysis-of-facebook-as-a-campaign-technology/.

Sano-Franchini, Jennifer, et al. Slack, Social Justice, and Online Technical Communication Pedagogy. Technical Communication Quarterly, vol. 32, no. 2, June 2022, pp. 134–148. https://doi.org/10.1080/10572252.2022.2085809.

Shepherd, Ryan P. FB in FYC: Facebook Use Among First-Year Composition Students. Computers and Composition, vol. 35, Mar. 2015, pp. 86–107. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2014.12.001.

Shepherd, Ryan P. Digital Writing, Multimodality, and Learning Transfer: Crafting Connections between Composition and Online Composing. Computers and Composition, vol. 48, June 2018, pp. 103–14. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2018.03.001.

Slack. Accessibility in Slack. Slack, https://slack.com/accessibility. Accessed 27 Oct. 2021.

Slack. Made for People. Built for Productivity. Slack, https://slack.com. Accessed 9 May 2023.

Tucker-Raymond, Eli, et al. Science Teachers Can Teach Computational Thinking through Distributed Expertise. Computers & Education, vol. 173, Nov. 2021, p. 104284. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compedu.2021.104284.

Vie, Stephanie. Digital Divide 2.0: ‘Generation M’ and Online Social Networking Sites in the Composition Classroom. Computers and Composition, vol. 25, no. 1, Jan. 2008, pp. 9–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2007.09.004.

Vie, Stephanie. Effective Social Media Use in Online Writing Classes through Universal Design for Learning (UDL) Principles. Computers and Composition, vol. 49, June 2018. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.compcom.2018.05.005.

Wardle, Elizabeth, and J. Blake Scott. Defining and Developing Expertise in a Writing and Rhetoric Department. WPA: Writing Program Administration - Journal of the Council of Writing Program Administrators, vol. 39, no. 1, Fall 2015, pp. 72–93.

Walls, Douglas and Vie, Stephanie, editors. Social Writing/Social Media: Publics, Presentations, and Pedagogies. The WAC Clearinghouse at the UP of Colorado, 2017. https://wac.colostate.edu/docs/books/social/foreword.pdf.

Witek, Donna and Teresa Grettano. Revising For Metaliteracy: Flexible Course Design to Support Social Media Pedagogy. Metaliteracy In Practice, edited by Trudi E. Jacobson and Thomas P. Mackey, American Library Association, 2016, pp. 1–22.

Nurturing Distributed Expertise from Composition Forum 53 (Spring 2024)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/53/distributed-expertise.php

© Copyright 2024 Jacob D. Richter.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 53 table of contents.