Composition Forum 17, Fall 2007

http://compositionforum.com/issue/17/

How Making Matters: Reconfiguring Composition Intersubjective Spaces

Man always creates something in the space that separates him from the Other or from the fulfillment of his desires.

—Joyce McDougal, Plea for a Measure of Abnormality

Salena’s digital composition “Dear Uncle Buddy” (Figure 1) - was created as an early assignment for a multimedia basic writing class in September 2005. Salena composed her multimodal work, a text and image “postcard” addressed to her uncle in New Orleans shortly after Hurricane Katrina hit, by downloading media images from the internet and recombining/resignifying them to create a new entity. Her statement is a call for people to come together and lend a helping hand, coupled with a critical assessment of what she sees as the country’s priorities – how America privileges oil/the economy over human need. Responding to her text as a visual argument, I can see that the images are organized around the central image of the American flag – “her thesis.” She also uses visual metaphor and principles of antithesis to guide her juxtaposition of elements as opposed to simply illustrating its meaning – the oil barrel and the images of cars at gas stations contrast with images of the flood victims’ suffering. As a teacher sympathetic to the aims of critical pedagogy, but wary of tendencies to reinscribe top-down teaching and learning dynamics, I’m also impressed by her “parasitical” rearticulation of the news-media images. I suggest that in her own way and from her own location, she begins to work the terrain of contemporary activist artists who “ride the dominant culture physically while challenging it politically” (Lippard 288). However, what is most intriguing to me here is the narrative surrounding its reception, what this student work (the student who created it is African American) does to the intersubjective space between students (I teach in a multicultural university setting), and between students and teachers (I am white). Judging from the comments and discussion that resulted, Salena’s creation clearly made an impact on the class that day, coming as it did in the initial weeks after the event, as news images began to make clear that this was not just an ‘act of God’ but an unfolding tragedy about race in twenty first-century America. I want in this essay to begin to explore just what it is this impact consists of and why it is a particular kind of impact connected to multimodal semiosis and reception. But for now, I offer the example as the first of several in this essay of what Krista Ratcliffe has called “cross-cultural dialogues” across “discursive intersections of “gender and race/ethnicity” (Ratcliffe 196).

Although her topic is viewers’ reception of recognized artworks within a museum context, Marguerite Helmers makes a similar point; specifically, how the transactional experience associated with viewing images enables individuals to revise narratives of self and build community. “Not only does the viewer bring to the work a body of assumptions,” Helmers writes, “the viewer is also changed by the act of viewing and returns to the community bearing that knowledge” (71). Speaking at the 2004 CCCC meeting, Anne Wysocki also alluded to the “generosity” involved in the act of a student sharing a text and image composition with classmates in which she told the complex story of a family member’s disability– a generosity extended to the conference audience, I would add, through her own sharing of the student multimodal text.

Although Wysocki did not specifically refer to questions of difference in her talk, I would argue that the above examples suggest important implications for thinking through intersections between multimodal semiosis and communicating across the gap between self and other. Yet while there have been many important arguments for expanding the study of visual rhetoric beyond text analysis paradigms to include multimodal production (e.g., “visual argument”: Faigley; George; “multiwriting” Davis and Shadle; Shipka), and while a strong thread of composition research has explored issues of race and difference in digital media and online spaces (e.g. “race”: Knadler; McKee; “gender”: Brady Aschauer; Hocks), researchers have paid scant attention to the here- and- now interpersonal connecting involved in sharing and responding to multimodal compositions. As Wysocki summarizes this research recently in Writing New Media: “There is little or nothing,” she writes, “about how with new media we make visible positions that engage others, that are structured so that they can give the socially-tied satisfaction and encouragement of producing ‘complex representations that invite argumentation’ (Brodkey 201)” (Wysocki 6).

In this essay, I explore what such a ‘socially-tied practice of making positions visible’ (my emphasis) might look like within a pedagogy of difference. To that end, I argue that working through processes of composing and responding across multiple modalities can create new conditions of possibility for previously marginalized students not only to gain a voice, but also to be heard and seen in new ways by classroom beholders. My particular interest lies in exploring how processes of making and responding to multimodal texts reconfigures what object relations theory understands as intersubjective space, the space between self and other. In order to construct my argument, I bring together insights from a recognizable group of composition theorists with psychoanalytic theorizations of creative process and intersubjectivity. My argument begins by examining two interconnected student works in order to show how bringing multimodal semiosis to composition facilitates another’s creative process, thus reconfiguring intersubjective space, and, in turn what I want to suggest as “social space” and the institutional “field of power” (Bourdieu 1998). I then explore a third student’s work and discuss how her text facilitates classroom beholders’ processes of revising narratives of self as part of revising relations with others. Before I do this, however, I find it necessary to first set a preliminary context with reference to fundamental object relations principles on creative process.

I am committed to the position articulated by D.W. Winnicott that “art” – and I want here to broaden this already broad definition of “art” to include what compositionists understand as multimodal semiosis - is “the adult equivalent of the transitional phenomena of infancy and early childhood.” (Winnicott 1965, 184). While the concept of the transitional object is well known to the point that the idea of the special significance of the child’s blanket has become a cultural cliché, what is frequently overlooked is that Winnicott is always speaking about a transitional relation, a triangulation between the mother, the baby, and the transitional object. In the primordial transitional relation, the transitional object, often a found object such as the famous blanket or toy, becomes the infant’s “first creation” – ask the child whether s/he “made this and it says “yes,” - and lays the template for the affect associated with later adult creative activity as well as playing a crucial role developmentally for later adult mutuality. Thus not only is this “potential space” the primary space of mutual relation, it is the source for the affect we tap into whenever we are creative, and this affect is at base, an affect of relationality.

Speaking (and Hearing) Difference

In discussing design, “the process of shaping emergent meaning,” The New London Group has argued that not only do meaning makers transform materials, in the process of their co-engagement in designing meaning, “people transform their relations with each other, and so transform themselves” (76). Extending her idea of the generosity of the multimodal text to envision a classroom open to the generosity of others, Wysocki similarly expresses the hope that “we would teach a generosity toward the positions that others produce … [for] the crafting of new media texts,” she argues, “is how we are able to produce and see our own positions within the broad and materially different communication channels where we all now move and work with others (23). Art Education researcher Terrence Heath also makes a similar point in an address to the NAEA on the role of art in our increasingly instrumentally-driven general education curriculum. He argues for the importance of “warm” art, an art that is “warmth, healing, and nourishment” by virtue of its being “active, innovative and shared” (33). While Heath’s subject is art education, I suggest many in composition who teach with new media would also recognize the life-giving or “biophilic” (Heath 26) power of the shared creation.

What follows are several student “multimodal rhetorical events”{1} across different media that I experienced in my composition classroom recently. Over the last few years, I have been introducing students in my classroom to a variety of contemporary multimedia artist as models for multimodal composing. Like many current multimodal composition pedagogies, this practice gives students an opportunity to inhabit the subject-position of “designer” and to expand the repertoire for making meaning beyond linguistic-only modes. But more than most, this pedagogy seek to refine the designer position by providing opportunities for students to appropriate and transform selected contemporary multimedia artists’ tactics. There are strong affinities between the pedagogical approach I outline and Geoffrey Sirc’s calls in Writing New Media for students to “take an art stance to the everyday, suffusing the materiality of daily life with the aesthetic” (117). However, whereas Sirc’s main focus in the above chapter is on seeking enabling models for new kinds of composing practices from the Modernist avant-garde – for example, offering the “box logic” of the composer as collector and re-arranger a la Joseph Cornell as an antidote to the “linear norm of essayist prose” (114) – I am looking more in this essay to artist-models who practice what are by now “classic” postmodernist moves of rearticulating avant-garde strategies of appropriation, juxtaposition, recombination, etc. within a more contemporary context as a way of effecting cultural critique.

Figure Two, Part One: “Mom and Grandma at Disneyland, 1975” by Javier Cervantes (detail; full image)

To that end, the student works in the first two interlinked examples were inspired by the photographer Carrie Mae Weems and the appropriation artist Nancy Chunn, respectively. The third student work, a video “walk” which I go on to later discuss in the last section of this essay was inspired by Canadian sound-artist Janet Cardiff. I chose these particular artists’ tactics as models because they enable specific kinds of agency. Both Weems and Chunn deploy text and image to create resisting representations. Weems’ Family Pictures and Stories (1978-84) began, she says, as a response to “official” documentary photography of the Black experience. By treating her own experience and that of her family as culture/folklore rather than as social condition, Weems responds to the pathologizing of the black family by the “imaging of black people as ‘other’ in the photodocumentary tradition” (Linker 80). I have found that her artwork dovetails well with composition emphases on “politicizing the personal” (Barnett 2006) and can enable students to see how “their personal histories are also their cultural histories” (Brodkey 209). Also working with text and image media, Nancy Chunn, on the other hand, deploys the kinds of parasitical tactics familiar to compositionists as “remix.” In her 366-piece installation, “Front Pages 1996,” Chunn transformed successive front pages from The New York Times over the course of the year 1996 by reproducing individual pages, then, through what critic Dan Younger calls “an extended daily act of mark-making using primarily pastels and stamps [she] gives herself the permission to ‘talk back’ to news events and their representation.{2}” As a “parasitic” (Lippard 288) method for resignifying existing “chunks” of dominant media culture in order to create new, oppositional meanings, Chunn’s method is a particularly good fit with critical composition pedagogies that seek to change students’ relationship with visual culture from one of consumption to production.

Figure Two, Part Two: “Mom and Grandma at Disneyland, 1975” by Javier Cervantes (detail; full image)

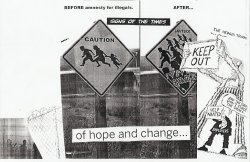

Javier, juxtaposed a photo of his mother and grandmother taken at Disneyland in 1975 when they first arrived in the United States from Sinaloa, Mexico with several lines of text in which he describes how she sought a better life for herself and her family (Figure 2, Part 1) and with a newspaper article from 1975 critical of immigration (Figure 2, Part 2). Linda, a young Latina woman, became very interested in Javier’s work when he shared it with the class. She proceeded to tell us that visiting Disneyland was something that a lot of Mexican families do when they arrive in the U.S., almost a rite of passage. Even as she laughed about it from her perspective as a second generation immigrant, she described how powerful she found Javier’s work and how she didn’t expect to encounter something like this at “school.” She then decided to create her own multimodal text, inspired, she told me by Javier’s. Also dealing with the topic of immigration, she parasitically appropriated and resignified a highway caution sign placed near San Onofre California on the road north from San Diego towards Los Angeles. While ostensibly placed on the highway for safety reasons, for many, the sign has become a metaphor for the invisibility and dehumanizing of illegal immigrants. Linda juxtaposed the original sign with a newspaper cartoon satirizing right wing proposals for building a wall across the border, an existing pro-immigrant internet media appropriation, and her own text copy (Figure 3). In her accompanying reflection paper, she writes how she wanted to show how, while feeling empathy for illegal immigrants - some of her own family members had come across the border this way – she still wanted to show the complexities of the situation by showing multiple sides, across the political spectrum.

In “Visual Rhetoric in a Culture of Fear: Impediments to Multimedia Production,” Steve Westbrook uses an example of an ad parody assignment to argue for how multimodal semiosis better enables students to challenge what he describes as a societal discourse that positions students within a “consumer-based paradigm” for engaging visual culture (465). Linda similarly challenges the docile student position through her own use of parasitical tactics. However, while this type of textual analysis is helpful for discussing the products of a multimodal semiosis pedagogy, I am still left with questions about what it is that actually took place on the intersubjective level. How, specifically, did Javier’s creation facilitate Linda developing her own speaking positions?

One vocabulary that I find useful for exploring these questions is object relations theorizations on creative process. In “The Expressive Gaze,” art critic Donald Kuspit argues that the transitional potential inherent in all types of creative activity can, under the right conditions, give rise to a powerful, if momentary, intersubjective experience catalyzed by the made-artifact. He writes:

A good creation affords not simply a superficial, conscious sense of social connection with the other, through the medium of the creation, but an unconscious sense of profound personal merger with the other. The other becomes a significant other, not simply another, that is, seems primary and supportive by virtue of the shared experience of the creation, which also seems primary and supportive. However short-lived this complex transitional illusion, it is absolutely necessary for the adult’s emotional well-being and sense of safety. (303)

This is a communication that while it may involve words is ultimately prior to/beyond language. In what I would argue is a statement that resonates with current calls for affective pedagogies (Edbauer 2002, Grossberg 1992) that bridge emotion and intellect, Kuspit calls the “transitional experience the antidote to the dissociation of sensibility” associated with what Winnicott calls “compliance,” or the “social self,” “with its sense of contradiction between, indeed the incommensurateness of cognition, and feeling” (301). What I want to suggest here is that Javier’s creation produced the effects it did because it was “good enough,” that is, it facilitated Linda’s existence for a brief but significant moment by supporting her creativity. If the “social self” is necessary for functioning in society and for psychic health, we are nonetheless always ready to revisit the primary (biophilic) affect associated with the transitional relation, Kuspit says, “reversing separation and experiencing merger, thus replenishing one’s sense of self”. Hence, the “hold” of transitionality and our life-long need for what Margaret Mahler calls “emotional refueling” (Kuspit 303). Along similar lines, in an insight that challenges the (masculinist) cliché of the figure of the lone artist, Heinz Kohut argues that it is this “mirroring” that produces what he terms “a transference of creativity,” a form of “uplifting,” (the mother first lifts up) essential for ensuring the plenitude of self necessary to function creatively (201). When viewed in this way, Javier’s creation functions not only as a transitional object within classroom intersubjective space, but becomes for Linda the kind of “facilitating internal object” required for what Winnicott calls “creative living” (Kuspit 345).

Javier’s multimodal text attests to how multimodal semiosis can open up new spaces for “previously marginalized students to speak with powerful voices against the mainstream” (Bizzell 7-9). However, as Bruce Horner and John Trimbur observe in “English Only and U.S. College Composition,” the act of speaking alone does not guarantee a hearing. They argue that in order for a voice to be recognized, it is not only a question of articulation but whether the speaker has what Pierre Bourdieu calls sufficient “linguistic capital” to be accorded the “legitimacy” to be “listened to, likely to be recognized as acceptable in all situations in which there is occasion to speak” (612). I am reminded of Susan Romano’s observations in her study in, “The Egalitarianism Narrative: Whose Story? Which Yardstick?” of an on-line classroom discussion situation on texts focusing on Latino culture in which Latinos were reluctant to speak as Latinos due to negative comments about their culture by Anglo students. In effect, the same social structures marginalizing their voices are reproduced in the online medium. The situation is comparable to Linda’s sense of her initial marginalized subject positions within what Bourdieu calls [classroom] “social space” and [institutional] “field of power.” Therefore, I want to suggest that Javier succeeded in imposing a hearing in the class that day through his multimodal text; the “fact” of its existence in classroom social space enabled Linda to build the linguistic capital and sense of self necessary to speak – as a Latina - and be heard in classroom social space and, in her own way, the institutional field (to the extent that our classroom represented an extension of “college composition”). I pose this sense of composition as possible transitional space, then, against its more typical, “gatekeeping/curatorial” (Sirc 2004) narrative.

Another sphere of cross-cultural dialogue in the multicultural classroom is involved in what feminist object relations theorist Jessica Benjamin calls “recognizing” an other and/or difference. In the remainder of this essay, I want to further develop my discussion of the multimodal composition classroom as possible transitional space, specifically, the role played by the multimodal text in facilitating what I go on to elaborate as moving from a posture of object relating to Object use.

Recognizing an Other and/or Difference

To look and be looked at is never a neutral process. As Kaplan reminds us,

The body and looking are the most primitive aspects of humans: like the body, which is territorialized by the mother early on, looking is constituted as the child learns the culture it finds itself in. It learns what to look at; what to avoid looking at; what is to be visible; what invisible; who controls the look, who is object of the look” (Kaplan 1997, xvi).

One such manifestation of a ‘circle of looks’ within the context of racialized looking relations in the multicultural composition classroom is explored by Kelvin Monroe in the 2004 special issue of College English, “Rhetorics from/of Color.” Monroe brings together Fanon’s concept of the colonial subject’s internalized “dual narcissism” and Du Bois’s concept of “Double Consciousness,” how “I have been internally colonized to look at myself with white others’ eyes” (105), to explore his experiences as a black teacher of composition at a multicultural college. He writes of how, from the moment he walks into the classroom and the university, he experiences what he calls the “interconnectedness of gazes” (116); how he finds himself “suffering from introjecting” what he thinks is his students’ image of him, i.e., how white students are looking at him as a black teacher - “Angry” at perceived racial injustices; how non-whites look at him - Is he “sellin out”?; and how colleagues are introjecting his expectations of how they should act, etc. (116-117). On their part, white subjects, Monroe suggests, must work through versions of what Fanon calls a collective “phobia” associated with the inability “to introject the Other’s image,” i.e., they are unable to “[identify] blackness without considering the body image-blackness” (116).

In what follows, I would like to lay the above framework alongside a third multimodal rhetorical event. Inspired by Ball and Lardner’s calls to tap into vernacular literacies by positioning students as “informed interpreters of the specifics of their experience,” (164) I asked students to compose a “walk” as an intervention in place and space. I also provided several sources of inspiration to extend the idea of walk, among these, sound artist Janet Cardiff. I had recently experienced Cardiff’s, Her Long Black Hair (2005), an interactive audio “walk” set in New York’s Central Park that weaves together Cardiff’s own voice with bits of fictional and historical narrative, ambient sounds, and choreographed images of existing park scenes. For Cardiff, the walk is a multimodal rhetorical event in the pure sense of the word; no longer the art object as discreet painting or sculpture bound within its particular hierarchical space, instead, the viewer’s experience of the environment or space itself and interactions with others constitute the artwork. I saw in Cardiff’s “walks” another opportunity for students to expand on remix rhetoric and the kinds of autoethnography projects Brodkey and Ball and Lardner discuss. I was intrigued by the possibilities for composing when site, sound, and landscape become composing media, and what happens when what we normally take as the most ordinary of actions, becomes a way to remake the familiar anew.

One such student “walk” stood out. Diana, a young African-American woman created a video with voice-over in which she invited the viewer to accompany her on a walk through her home. She composed a powerful aural and visual autoethnography revolving around the meaning of place in which she shared her good feelings for her current home and described how proud she is now that her daughter will have a chance to grow up in this nurturing space. Diana describes her walk as a response to comments by a white woman student, Lisa, who had earlier made some most likely well-meaning yet unexamined remarks about what she called “the stress and difficulty of being black.” Earlier, while conferencing the paper with me, Diana had mentioned that, “To her, I look like some ghetto black girl.” While Diana’s characterizations of her classmate’s perceptions may or may not have been accurate, it seems reasonable to assume that up to that point, both were operating under a version of the “interconnectedness of gazes” Monroe discusses.

In “The Shadow of the Other (Subject)” (1994), Jessica Benjamin explains the “problem” the Other poses for the subject in this way:

An intersubjective theory of the self is one that poses the question of how and whether the self can actually achieve a relationship to an outside other without, through identification, assimilating or being assimilated by it. This question—how is it possible to recognize an other?—may be taken as a different form of the problem addressed by much feminist writing, that of respecting difference, or rather multiple differences. (Jessica Benjamin 231)

One project for enacting cross-cultural dialogues is what Krista Ratcliffe calls “rhetorical listening.” Such a stance seeks to “hear discursive intersections of gender and race/ethnicity” in order to “first [identify] the various discourses embodied in each of us and then [listen] to hear and imagine how they might affect not only ourselves but others” (196-206, quoted in Ballif, et al. 588). Summarizing critical listening postures recently, Jill Swienciki writes that such a practice requires “adopt[ing] the posture of a listener… accepting that I have a lot to learn… it means resisting mastery and moving, as all genuine inquiry does, from one question that depends on and expands into others, enriching contexts and experiences along the way” (354). But if as many researchers have claimed, new media not only changes “writing” itself, but also what Wysocki takes as the “materiality” of the writing classroom (included among Bruce Horner’s list of such materialities are social relations between classroom agents), what new possibilities for classroom intersubjective relations open up as a result? In turn, how might we expand listening theories to accommodate such a reconfigured classroom space?

I take from Fanon’s (and Monroe’s) work that it is not enough to focus solely on the “rational” level of social interaction when investigating questions of recognizing an other and/or difference. As Benjamin states, “To articulate the conditions for recognizing an other, we must understand the deepest obstacles within the self…” (232); specifically, we need to account for the role of negativity in the encounter between self and other, its inevitability and its productive function. “The mere existence of others as separate beings,” she writes, “reflect our dependency and lack of control” thus presenting a threat to the self’s sense of infantile omnipotence (240). Second, there is also the negativity associated with the process of “making abject” associated with racism and sexism, the compensatory projecting onto the other of the hated, repudiated part of the self in order to secure one’s identity as that which one is not. (note: Kristeva, etc,) Yet it is this negativity, if worked through, Benjamin argues, which creates the conditions of possibility for recognizing an other as other with an independent existence, one able to impact on and affect one’s own existence. This is what Winnicott calls developing the capacity to “use” an object as opposed to more immature forms of “relating.” It requires that the object be “destroyed” in fantasy, be placed, in other words, “outside the area of objects set up by the subject’s projective mental mechanisms” and “survive” this destruction without withdrawing, reacting punitively or submitting. The “reward” for this destruction is that the object is now someone that can be loved rather than introjected as the self’s object. As Winnicott puts it, “a world of shared reality is created which the subject can use and which can feed back other-than-me substance into the subject” (94).

It is important to note that for Winnicott, there is no “anger” accompanying this process of “attack” and “destruction,” as the primary transitional relation takes place before the subject’s “encounter with the reality principle” (93). Whereas for Benjamin, her concept of working through the negativity of difference also encompasses later emotions such as the anxieties and hatred associated with racism and sexism. So for that matter Helga Geyer-Ryan, who while writing on the psychic roots of xenophobia and racism similarly stresses the importance of accessing primary processes of symbolization “where anxieties can be externalized and new identities internalized” (123). She goes on to argue following Kristeva’s insights on healing the split subject foundational to patriarchal culture, that “only the lifelong, cathartic experience and reliving of that division [the primary splitting of conscious and unconscious processes] through art or other imaginative practices can prevent or mitigate the petrefaction of the imaginary self” (123). For me, a process that combines these insights might be best of all. Hence, what I am arguing for as the importance of 1) conceiving the multimodal semiosis classroom as a potential transitional space, and 2) developing a good-enough facilitating environment for the process to play itself out, i.e., providing the tools, safety, challenge, etc.

Like Linda’s re-signage, Diana’s work similarly counters the docile student subject position. Her walk enacts what hooks calls a tactics of “talking back.” She resignifies the gaze, not through confrontation but by extending an invitation to classroom beholders to share her company. Countering the “angry-self” projections Monroe talks about, her voice is warm, not angry, even though as she writes in her accompanying reflection paper, she was made upset by Lisa’s comment. After viewing the video, Lisa, spoke up again and commented favorably on her experience as a viewer. In her own reflection paper, she talked about ‘how moved she was by the video; how she knew Diana from her classes but never like this, as a mother and a daughter.’

Diana’s Walk showed the potential generosity that the multimodal creation can bring to the composition classroom. While I would not presume to capture what happened in the classroom that day within a schematic or a theory and while I recognize that my position as an observer is always partial and informed by my own needs for narcissistic cathexes, I would like to suggest that Diana’s Walk also acts transitionally. In this instance, it facilitated Lisa’s moving from approaching the other through a posture of relating to one of object use by enabling Lisa to work through processes of destroying in fantasy her initial assimilative projection of the other. On her part, Diana survived “the attack” by responding not with anger or by withdrawing but through a creation that was good-enough to momentarily facilitate Lisa’s existence. Based on her comments in class and on what she later wrote, then, it would seem that Diana’s Walk had a transitional impact on Lisa. As Benjamin explains, it is “an act that breaks into the other’s absolute identity with her-or himself in such a way that the other is no longer exactly what he or she was a moment before… This process of negation, acting on the other and being recognized – Winnicott’s destruction with survival – is initially the opposite of the turning in on the self. (Benjamin 1995, 210; quoted in Kaplan 1997, 302).

What, then, of these possible new awarenesses? We do not know if they will last, or if they will be carried outside the classroom. After witnessing several other moments of tension between Lisa and Diana as the semester wound down, I wonder about the permanence of this intersubjective moment. Still, if the image/multimodality is properly associated with the unconscious realm of the Imaginary, changes in the beholder can occur on a level not immediately apparent. As art historian James Elkins writes of the effects he expects pictures to have on him in The Object Stares Back: “That new mood might become a part of you, recurring months or years later in very different circumstances” (41). I also learn from these experiences that I need to remind myself that within the transitional relation, it is the responsibility of the Other to survive the subject’s attack, to become “one who entertains the double identification,” Benjamin says, “recognizing the position of the subject without wholly abandoning her position, who is thus relieved of persecutory aspects” (249). I feel that on that score, I had not been entirely successful. I realize now that I had overly identified with Diana’s success and had inadvertently been guilty of a version of consuming the other, what Benjamin cautions as the assimilative introjection associated with making “identification with the outside Other into an unquestioned position of the ‘good’” (234). Would I have modelled better pedagogy had I tried to facilitate Diana in listening more empathically to Lisa? This too is the challenge of opening one’s classroom to the generosity of multimodal semiosis.

Notes

- I am borrowing Jody Shipka’s term here. I find it helpful for framing the student multimodal text within a process of making and reception that necessarily takes place between two ore more people and occurs across space and time. (Return to text.)

- See http://www2.kenyon.edu/ArtGallery/exhibitions/9900/chunn/chunn.htm. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

Ballif, Michelle, D. Diane Davis, and Roxanne Mountford.“Toward an Ethics of Listening." JAC: A Journal of Composition Theory 20.4 (2000): 931-942.

Ball, Arnetha F. and Ted Lardner. African American Literacies Unleashed: Vernacular English and the Composition Classroom. Carbondale: Southern Illinois University Press, 2005.

Barnett, Timothy. “Politicizing the Personal: Frederick Douglass, Richard Wright, and Some Thoughts on the Limits of Critical Literacy”. College English 68.4 (2006): 356-381.

Benjamin, Jessica. “The Shadow of the Other (Subject): Intersubjectivity and Feminist Theory.” Constellations 1.2 (1994): 231-51.

Bizzell, Patricia. “Hybrid Academic Discourses: What, Why, How.” Composition Studies. 27.2 (1999): 7-21.

Bourdieu, Pierre. Language and Symbolic Power. Ed. John B. Thompson. Trans. Gino Raymond and Matthew Adamson. Cambridge MA: Harvard University Press, 1991.

———. Practical Reason: On the Theory of Action. Stanford CA: Stanford UP, 1998.

Brodkey, Linda. Writing Permitted in Designated Areas Only. Minneapolis: University of Minneapolis Press, 1996.

Brady Aschauer, Ann. “Tinkering with Technological Skill: An Examination of the Gendered Uses of Technologies” Computers and Composition 16.1 (1999): 7-23.

Davis, Robert and Mark Shadle. “Building a Mystery: Alternative Research Writing and the Academic Act of Seeking.” CCC 51.3 (2000): 417-446.

Edbauer, Jenny. “Big Time Sensuality: Affective Literacies and Texts That Matter.” Composition Forum 13.1 and 13.2. (2002): 23-37.

Elkins, James. The Object Stares Back: On the Nature of Seeing. San Diego: Harcourt, 1997.

Faigley, Lester. “Material Literacy and Visual Design.” Rhetorical Bodies. Eds. Jack Selzer and Sharon Crowley. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press, 1999. 171-201.

Faigley, Lester, Diana George, Anna Palchik, Cynthia Selfe. Picturing Texts. New York: Norton, 2004.

George, Diana. “From Analysis to Design: Visual Communication in the Teaching of Writing.” CCC 54.1 (2002): 11-39.

Geyer-Ryan, Helga. “Imaginary Identity: Space, Gender, Nation.” Vision in Context: Historical and Contemporary Perspectives on Sight. Eds. Teresa Brennan and Martin Jay. New York: Routledge, 1996. 117-125.

Grossberg, Lawrence. We Gotta Get Out Of This Place. New York: Routledge, 1992.

Heath, Terrence. "Warm Art." Keynote address given at the Convention of the National Art Education Association, Phoenix AZ, 1-5 May, 1992.

Helmers, Marguerite. “Painting as Rhetorical Performance: Joseph Wright's An Experiment on a Bird in the Air Pump.” Journal of Advanced Composition 21.1 (2001): 71-95.

Hocks, Mary E. “Feminist Interventions in Electronic Environments.” Computers and Composition 16.1 (1999): 107-19.

hooks, bell. “In Our Glory: Photography and Black Life” Art on My Mind: Visual Politics. New York: The New Press, 1995. (54-64).

Horner, Bruce and John Trimbur. “English Only and U. S. College Composition.” CCC 53.4 (2002): 594-630.

Kaplan, E. Ann. Looking for the Other: Feminism, Film, and the Imperial Gaze. New York: Routledge, 1997.

Knadler, Stephen. “E-Racing Difference in E-Space: Black female Subjectivity and the Web-Based Portfolio.” Computers and Composition 18.3 (2001): 235-55.

Kohut, Heinz. How Does Analysis Cure? Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1984.

Kuspit, Donald. “The Expressive Gaze.” Idiosyncratic Identities: Artists at the End of the Avant-Garde. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1996. 300-313.

Linker, Kate. “Went Looking for Africa: Carrie Mae Weems.” Artforum. February (1993) : 79.

Lippard, Lucy. The Lure of the Local: Senses of Place in a Multicentered Society. New York: Norton, 1997.

McDougal, Joyce. Plea for a Measure of Abnormality. New York: Brunner/Mazel, 1992.

McKee, Heidi. “YOUR VIEWS SHOWED TRUE IGNORANCE!!!”: (Mis)Communication in an Online Interracial Discussion Forum.” Computers and Composition 19.4 (2002): 411-34.

Monroe, Kelvin. , “Writin da Funk Dealer: Songs of Reflecttions and Reflex/shuns.” College English 67 (2004): 102-20.

New London Group. “A Pedagogy of Multiliteracies: Designing Social Futures.” Harvard Education Review 66.1 (1996): 60-92.

Ratcliffe, Krista. “Rhetorical Listening: A Trope for Interpretive Invention and a Code of Cross-Cultural Conduct.” CCC 51.2 (1999): 195-224.

Romano, Susan. “The Egalitarianism Narrative: Whose Story? Which Yardstick?” Computers and Composition 10.3: 5-28

Shipka, Jody. “A Multimodal Task-Based Framework for Composing.” CCC 57.2 (2005): 277-306.

Sirc, Geoffrey. “Box Logic.” in Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for Expanding the Teaching of Composition. (11-14).

Westbrook, Steve. “Visual Rhetoric in a Culture of Fear: Impediments to Multimedia Production.” College English 68 (2006), 457-480.

Winnicott, D.W. “Communicating and Not Communicating Leading to a Study of Certain Opposites,” The Maturational Process and the Facilitating Environment. New York NY: International Universities Press, 1965.

———. Playing and Reality. New York: Routledge, 1991.

Wysocki, Anne Frances. “Opening New Media to Writing: Openings and Justifications.” Writing New Media: Theory and Applications for Expanding the Teaching of Composition. Eds. Anne Frances Wysocki, Johndan Johnson-Eilola, Cynthia L. Selfe, andGeoffrey Sirc. Logan UT: Utah State University Press, 2004. 1-41.

———. “Some Things That Matter about Digital New Media for Composition.” Conference on College Composition and Communication. San Antonio, TX, 27 March 2004.

“How Making Matters” from Composition Forum 17 (Fall 2007)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/17/how-making-matters.php

© Copyright 2007 David P. Sherman.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 17 table of contents.