Composition Forum 23, Spring 2011

http://compositionforum.com/issue/23/

Rekindling Longwood University’s Rhetoric and Professional Writing Concentration and Minor, 2007-2010

Abstract: The challenges of redesigning and reviving Longwood University’s Rhetoric and Professional Writing program involved skills in collaboration, negotiation, and advertisement. While unexpected obstacles arose, taking an honest look at the existing program design and working to maintain the focus on rhetoric helped to circumvent failure. Finally, student involvement, student feedback, and the use of online resources became key elements in bringing a weak program to life.

Introduction

The impetus to adopt Professional and Technical writing programs is growing significantly, but many people building these programs do not include courses specifically devoted to rhetoric in their design. Part of this exclusion has to do with where Professional and Technical writing programs are housed within the university, since, as Dragga points out, a program’s identity and priorities are heavily influenced by its location on campus (221). The July/September 2010 special issue of Technical Communication Quarterly examines the positioning and identity of technical communication programs when they move out of English Departments and either stand alone or attach themselves to Communication or Engineering Departments (Dragga 221). At stake in these migrations is the status of rhetoric as a subject of study and a mode of analysis. Within English departments, as Rentz, Debs, and Meloncon note, rhetoric is a legitimized, sanctioned subject (282). What this means is that rhetoric courses may be more easily accepted in professional and technical writing programs housed within English Departments than in stand-alone professional and technical writing programs. While rhetoric certainly provides a basis for professional and technical writing programs wherever they are located, courses devoted solely to rhetorical criticism, history, or analysis are not necessarily part of every technical writing program, which has implications for how students read and produce professional and technical documents. In the case of redesigning and revising the Rhetoric and Professional Writing Program at Longwood University, being a part of the English Department made it easier to argue for courses devoted to rhetoric alone.

Although my position in the English Department at Longwood University is a result of a long-held desire to provide a way for students to develop professional writing skills in order to make pursuing a degree in literature a bit more “practical” for the job search after graduation, I owe much to those colleagues who successfully argued to include rhetoric in the scope of this program. While it is well-known within my field that the coursework in professional writing programs is grounded in rhetorical theories, the inclusion of courses focusing solely on learning the theories of rhetoric and on using rhetoric as a lens for analysis was key to providing channels for a fuller engagement of theory through research and analysis apart from the practical application and creation of workplace documents. Without courses devoted solely to the study of rhetorical theories, professional and technical writing programs sacrifice a valuable complementary perspective. Rhetoric’s body of texts on theory and analysis—as they have recursively emerged over the centuries—adds a different, but essential, type of intellectual depth to the program. While professional and technical writing courses focus on the creation of documents, the rhetoric courses focus much more heavily on issues of language, power, and epistemology, with a concentration on writings by Foucault, Cixous, Booth, or any number of other influential rhetoricians, such as one might find in Bizzell and Herzberg’s Readings from the Classical Times to the Present anthology, which is widely used in many rhetoric courses.

In addition, in a course such as Longwood’s English 303: Visual Rhetoric and Document Design, the marriage of rhetoric and professional writing may be capitalized upon as well. In the first half of the course, students explore rhetorical theories about power, interpellation, interpretation, and the making of meaning through Sturken and Cartwright’s Practices of Looking. In the second half of the course, Kostelnick and Robert’s Designing Visual Language textbook is used to create a range of documents, from brochures to flyers. The students round out the semester by writing a short critique of a workplace document and a longer research paper analyzing a visual element of their choice by illuminating its rhetorical capacities in the context of the theories covered in the first half of the semester. This course is just one example of how students have the opportunity to graduate from the program with well-honed critical thinking skills and practices (both pragmatic and praxis) that will prepare them for the job market.

Longwood places a huge emphasis on getting students into the workplace upon graduation. According to its website, Longwood University is a small university, serving around 5,000 students, and about 85% of these students are undergraduates (“About Longwood”). Longwood boasts a 90% job placement rate and at least partially attributes this to the required internships embedded in the General Education Program. U.S. News and World Report’s article “Degrees are Great, but Internships Make a Difference” highlights the effects internships have on student success in the job market, pointing out Longwood’s commitment to them as well as the fact that 74% of the 2008 graduates got jobs in a tough economy (Burnsed). Clearly, preparing students for the workplace is a central focus, as a perusal of Longwood ads will quickly confirm. Thus, building a program within the English Department that would enable English majors to get better jobs was welcomed when first proposed about ten years ago and is a central reason that an internship is required in the concentration. Students also have to complete a client project (such as designing a small website, creating a flyer, making a brochure, etc.) in English 470/570: Professional Writing and Editing, a required course in both the concentration and minor.

By tying rhetoric to professional writing at our small university, we can still offer courses that have a practical aspect to them, such as Technical Writing, but retain the right to explore more theory in courses such as the History of Rhetoric or Rhetorical Criticism. Rhetoric courses give students the background needed to engage with the articles analyzed in Technical Writing at a much deeper level than is afforded to students who lack the rhetorical knowledge. For example, I assign articles in my Technical Writing class that include Stephen Katz’s “The Ethics of Expediency,” Lisa Tyler’s “Ecological Disaster and Rhetorical Response,” and Dorothy Winsor’s “The Construction of Knowledge in Organizations.” Without addressing rhetorical theories such as the nature of epistemic rhetorics in relationship to Winsor’s article, without becoming familiar with the ethical dimensions of the “good” orator rooted in classical theories in Katz as well as the controversies of technological determinism of today, and without the attention to the rhetorical situation of the Exxon response as discussed by Tyler, the vibrant interplay between rhetoric and technical writing gets lost. What Carolyn Miller accomplished in 1979 with “A Humanistic Rationale for Technical Writing” is to illustrate the “positivistic assumptions” behind science and thus behind technical writing (613). Her 1992 chapter “Kairos in the Rhetoric of Science” brings to light the effects of the rhetorical situation for rhetoricians who must deal with probability, not just the realm of objectivity and certainty (313-14). She credits Charles Bazerman with his definition of “science as an agonistic enterprise” and as an “epistemic struggle” with the “making of opportunities for belief” (324). It is kairos, she argues, that allows for advancements in the emerging field of science, and it is kairos that enables rhetors to capitalize on the temporal openings that allow for change. Clearly, Miller’s work emphasizes the fact that one field enhances the other, and productive insights are lost when the connection is broken. Thus, courses in rhetorical theories and the analysis of non-fiction texts and/or visual elements clarify the process of the social construction of workplace documents. Instead of creating boilerplate documents dislodged from the complexity of human relationships and social/legal/ethical consequences, workplace documents are revealed to be a site of negotiation; they are understood in the contexts of the possibilities for positive social change, which are embedded in the creation and the use of them to advance the ideologically-grounded vision that drives a workplace forward.

Background

The history of the Rhetoric and Professional Writing program at Longwood reveals some important changes over the past decade. The program began as a minor in Journalism and Professional Writing, and a perusal of the 2001 undergraduate catalog reveals that students were required to take a course in the Introduction to Journalism, Linguistics, and Professional Writing. An Internship was also required. The electives included Technical Writing, Grammar, some Creative Writing courses, and a Graphic Design course taught by the Art Department. Clearly, responsibility for teaching the courses was spread out between professors within the English department and the Art Department, which taught one course. Thus, the initial strategy for building the program was conservative in comparison to the 24-credit-hour concentration and 18-hour minor students choose from today.

The conservative approach to building the program remained in place for the next few years. The 2005 catalog shows a small change when Technical Writing changed from a 200-level course to a 300-level course, but no changes were made beyond that. However, in 2006, the catalog shows that a concentration in Rhetoric and Professional Writing became available for the first time and that the term “Journalism” was eliminated except in the title of electives for the minor. The structure of the program remained the same, except that two new courses were added: History of Rhetoric and Rhetorical Criticism.

While information on the rationale for adding these courses has been lost, my assumption is that former faculty members drew upon arguments similar to the one made in the introduction to this article to justify the additional courses. Even though the courses were needed, they did not do well. Except for one semester when History of Rhetoric was allowed to run with only five students and another semester when Rhetorical Criticism barely avoided being cut after just eight students enrolled, interest was very low. Nevertheless, I wanted to keep these courses, but the program would need to be advertised, and the support of my colleagues was going to have to be an integral part of the plan. When History of Rhetoric didn’t attract a single student in the fall of 2007 (my first semester at Longwood), it became my goal to update the existing program without losing its focus on rhetoric.

Courses to Eliminate

My first idea for redesigning the program was to eliminate the journalism course. I had several reasons for doing so. First of all, the campus newspaper had left the English Department for Communication Studies long ago, and the last professor who taught Journalism in the English Department was gone by the end of the 2007-2008 year. Thus, the department did not have an instructor for the one journalism course left in the Rhetoric and Professional Writing Minor, nor did it have a place for students to practice those skills within the department. Second of all, Communication Studies offered both a Basic and an Advanced Media Writing course. The Communication Studies department embeds these courses in a Mass Media Concentration that prepares students for careers in “print reporting, writing and production, broadcast writing, production, and editing, and creation of digital communication” (“Mass Media”). By directing the focus of the Rhetoric and Professional Writing program toward writing done in organizations (as opposed to media or journalism), such as in the sciences or in a corporation, the program would not duplicate efforts of preparing students for the workplace.

A second cut was to the Creative Writing courses offered as electives in the minor. While many professional writing programs include creative writing courses, I wanted to hone the focus of the Rhetoric and Professional Writing program on non-fiction writing. Eliminating the courses from the minor would not affect the Creative Writing Program. It was and still is a thriving program that attracts students from throughout the English major with four tracks of study: Poetry, Fiction, Creative Non-Fiction, and Dramatic Writing (“2007-2008 Catalog”). Thus, I chose to take out English 316: Writing Fiction, and English 317: Writing Poetry. I chose to keep English 318 and English 478, however, which are the regular and advanced creative non-fiction writing courses. These courses maintained the focus I desired and spread out the responsibility for teaching the courses to other faculty so I would not be carrying the full responsibility for teaching all of the courses in the concentration or minor on my own.

As I continued to take stock of the existing program, I made additional cuts. I discovered the Graphic Design course was unpopular because it had another art course as a prerequisite, so for students to take it, they had to take six hours instead of three. Since the minor added eighteen hours to the English major, adding three more hours did not appeal to most students, so they simply elected not to take the course. The other course I wanted to cut was Linguistics. Since the course had recently been changed to accommodate a new ESL program, it no longer seemed relevant for the Rhetoric and Professional Writing program in light of the goals that I had begun to sketch out for shaping the program.

The choice to eliminate a course from an existing program should primarily be driven by the mission of the program. As I wrote the goals for the Rhetoric and Professional Writing program, the two top goals were as follows:

Students will learn to analyze professional cultures, social contexts, and audiences to determine how they shape the various purposes and forms of writing, such as persuasion, organizational communication, and public discourse.

Students will learn to develop and understand various strategies for planning, researching, drafting, revising, and editing documents that respond effectively and ethically to professional situations and audiences (Welch, homepage, 2009).

The Creative Writing and Journalism courses did not further these goals, and the Graphic Design course did not focus on the creation of workplace documents, nor did it put the creation of those documents into the context of rhetorical theories that illuminate the social, ethical, or legal dimensions within the constructs of human relationships differentiated by status and power. As a result, these courses were eliminated.

Courses to Keep

To begin constructing a plan for updating the program and to help make a case for redesigning it, I took stock of the other courses already included. Two courses were doing well in 2007 and still are in 2010—English 470/570: Professional Writing and Editing and English 319: Technical Writing. The Professional Writing and Editing course has a small graduate section offered every time the undergraduate course is put on the schedule. It is an option for the MA degrees offered in the English Department, and many students choose to take it. Professional Writing and Editing is also an option in the Creative Writing Concentration, a “strongly recommended” elective for Political Science majors, and a requirement for the Communication Sciences and Disorders majors. While neither Business nor Communication Studies chooses to include the course in their programs, instead choosing to offer a similar course taught by faculty from their own departments, the course is still quite popular. The course entails instruction in writing memos, reports (formal and informal), proposals, a variety of genres of business letters (international, bad-news, cover letters, sales, etc.), emails, websites/online writing, resumes, and presentations that rely on PowerPoints, handouts, and other written materials. Students are required to complete a project with a client as well, a sort of mini-internship or service-learning project. Discussions include a focus on the contexts and kairos of workplace communication (social, hierarchical, legal, ethical), user-centered prose, grammar, document design, and establishing a professional ethos. While the sources drawn upon to fuel these discussions vary from semester to semester, the course is more than a “how-to” class. It drives toward an attention to praxis.

Technical Writing is an undergraduate course that is required for Computer Science majors as well as Rhetoric and Professional Writing concentrators and minors. The course provides instruction in precise, concise, accurate, user-centered writing. Students are required to create a user manual for an operation. Other assignments vary but might include work in translating a scholarly article into a website for a non-expert audience; reading and summarizing articles that deepen students’ understanding of technical writing and that emphasize a concise representation of key ideas in the longer text; and carrying out focused analyses of workplace documents drawn from textbook exercises and case studies.

As we continue to build the program, our hope is that the new nursing program, begun in fall of 2009, might eventually require the course and that students from other majors will take the course as well. In a recent workshop taught by WAC specialist, Dr. Terry Myers Zawacki of George Mason University, faculty from the Math and Science Departments recently came together with Humanities faculty in order to explore ways to use writing in the classroom.{1} In the workshop, they expressed a need for instruction in the types of precise, user-centered writing taught in Technical Writing. In my follow-up communications with them, I hope to emphasize the value of the course, as well as to create an informal WAC group to continue the momentum gained by the workshop.

New Courses to Add

After meeting with my colleagues and building some consensus with faculty in the department in 2007-2008, I began to overhaul the program in the fall of 2008. In light of the first two programmatic goals—to teach students to analyze contexts to reveal how they shape document creation, and to teach students to recognize and understand the rhetorical decisions involved in drafting a workplace document—the program needed to be grounded in its new vision, and the new courses needed to further that vision. In addition to the first two goals, I added several more:

Students will learn to understand and use various research methods (annotated bibliographies, library databases, interviews of professionals or other types of real-world research) to produce professional documents and/or analytical research papers.

Students will learn to develop strategies for using and adapting various communication technologies (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, web design programs, etc.) to manage projects and produce informative and usable professional documents.

Students will learn to argue with visual data, and to understand and implement various principles of format, layout, and design of professional documents that meet multiple user and reader needs.

Students will learn to use rhetoric as means of analyzing a document, situation, or other artifact.

Students will learn to use knowledge about rhetoric as a way to successfully and ethically practice persuasion. In other words, students will come to understand and connect the theories learned to the practical application of those theories in real-world contexts.

Students will learn to hone critical thinking skills through summary, analysis, response, critical inquiry, synthesis of research with their ideas, etc. (Welch, homepage, 2009).

Working with the thoughtful suggestions of the undergraduate curriculum committee chair, Dr. Shawn Smith, I designed two new courses that supported the goals set for the program:

English 303: Visual Rhetoric and Document Design, and

English 305: Advanced Topics in Rhetoric and Professional Writing.

The Visual Rhetoric and Document Design course was to be required in both the concentration and minor. Technically, it would take the place of the old Introduction to Journalism course, but in content and application, it would replace the Graphic Design course with material specifically designed for our concentrators and minors. The course was designed to draw upon the wealth of scholarship being done on theories of visual rhetoric and then apply this knowledge to the practice of designing workplace documents. The creation of this course would effectively provide a place to connect theory to practice in a focused way and to illustrate how much an exploration of rhetorical theories in visual rhetorics informs the way workplace documents are built and rhetorically analyzed. During the semester, students would be asked to construct multimodal compositions and workplace documents. Even though teaching and assessing multimodal writing are considerably more difficult tasks, the experience of creating multimodal workplace documents is increasingly being recognized as needed for competency in the workplace, as well as in the classroom (Potts; Vasudevan, Schultz, and Bateman). In “Convince Me!” Cynthia Selfe and Richard Selfe provide several reasons for an emphasis on multimodal writing, including a need for understanding and using “multiple channels of communication” and for meeting the changing demands of the workplace and its “literacy demands” (84-86). The new “literacy demands” include competency in visual, as well as textual, communication and document design. Since workplace writing combines expertise in both visual as well as textual concerns, these literacy demands easily translate into a need for more instruction in visual design and the theories that illuminate the significance of the rhetorical choices made in that design process. Thus, the new course would effectively update the program as well as attract students to its focus on a subject they would find both intriguing and practical.

I also wished to add English 305: Advanced Topics in Rhetoric and Professional Writing. The course would provide a place for advanced work in rhetoric and/or professional writing. For example, this fall I taught a women’s rhetorics course, but someone else might teach a course on grant writing using the same course designation. The course would be an answer to a very practical concern. As a Ph.D. in Rhetoric, Composition, and the Teaching of English, I was informed by the chair of the English Department that I would not be allowed to use English 495: Special Topics for teaching courses focused on research done in my field. One reason was that faculty allowed to teach a special topics course often had to wait three or more years to do so because of the high demand for teaching a course that focused on a faculty member’s specialized knowledge. Another reason was that the English 495 course would “count” for any English major and thus needed to cover some aspect of literature. As I was already anticipating the addition of a new faculty member from my field, I wanted a course that he or she could teach based upon his or her own specialized research interests, as well as a course I could teach based on mine. So, I designed the advanced topics course so it could vary in focus from digital rhetorics to women’s rhetorics (my area of interest) to grant writing to whatever I or a new faculty member might wish to teach.

When designing or redesigning a program, it is crucial to allow for growth, such as the English 305 course will allow for, without having to revisit the design of the program to accommodate future colleagues or emerging interests in the field. Admittedly, while others might find it easier to simply add new courses that reflect developing interests or new areas of expertise of newly hired faculty, since our university and program are small, being frugal is an important factor for us. At Longwood, instead of having a long list of courses that are offered periodically, more stability was required to make the program sustainable. That meant we had to limit the number of courses in the concentration in order to be sure they were offered often enough to accommodate the students in the program. Thus, we had to narrow the curricular requirement to one course (Advanced Topics) that would allow for much more flexibility than one set topic for a regular course would allow.

The Revised Concentration

In the end, the revised Concentration in Rhetoric and Professional Writing would require eight courses (24 hours). Two of the courses, Rhetorical Criticism and History of Rhetoric, would be entirely devoted to rhetoric; two would be devoted (with a rhetorical backdrop) to writing, namely Technical Writing and Professional Writing; one would be devoted to writing with little or no critical attention to rhetoric (Creative Writing Non-Fiction); one would be a blend between the two (Visual Rhetoric and Document Design); and the Advanced Topics course would allow for deeper explorations in any combination the instructor wished to construct. The curriculum for the new program is as follows:

English 301: Rhetorical Criticism (3 hours)

English 302: History of Rhetoric (3 hours)

English 303: Visual Rhetoric and Document Design (3 hours)

English 305: Advanced Topics in Rhetoric and Professional Writing (3 hours)

English 318: Creative Writing Non-Fiction (3 hours)

English 319: Technical Writing (3 hours)

English 470: Professional Writing and Editing (3 hours)

English 492: Internship (3 hours)

In the new design, the minor, which only requires 18 credit hours instead of 24, would include these required courses:

English 303: Visual Rhetoric and Document Design (3 hours)

English 319: Technical Writing (3 hours)

English 470: Professional Writing and Editing (3 hours)

The old program had formerly excluded the courses in rhetoric in choices for electives, but the new program would include them in order to encourage students minoring in the program to enroll. Students have to take three courses, or a total of 9 credit hours, from electives. The new list would look like this:

English 301: Rhetorical Criticism/3 credits

English 302: History of Rhetoric/3 credits

English 305: Advanced Topics in Rhetoric and Professional Writing/3 credits

English 318: Creative Writing Non-Fiction/3 credits

English 382: Traditional and Modern English Grammar/3 credits

English 478: Advanced Creative Writing Non-Fiction/3 credits

English 492: Internship in Professional Writing/3 credits

Thus, the new concentration fit the program’s goals much better than the old list of courses, and the minor offered the rhetoric courses a better chance to “make” as well as helped fulfill the goal for every student concentrating or minoring in Rhetoric and Professional Writing to build a background in rhetoric and writing. The internship allowed for students to put those rhetorical skills to use and increased the opportunity to land a first job. The retention of the grammar course was a compromise that was justified because students who have already taken a course or two that fits in the minor will sometimes pick it up because it enhances their marketability upon graduation. Fashioning the concentration and minor was a process that required me to view the program from my perspective, in light of the program’s newly defined goals, but also from the student’s perspective, in light of how he or she might find a place within it and why that place might be attractive.

Mediating Objections

As anyone who has revised a program knows, gaining approval at all levels for major changes is not an easy process. As expected, one of the objections to changing the program was a concern about staffing. At the time, I was the only full-time faculty member who was qualified to teach the courses in rhetoric. However, the two other full-time faculty with sub-specialties in rhetoric made it clear that they could arguably teach at least one course in the concentration. This seemed to nullify the objection, since if I left unexpectedly, the program would be able to continue. It also left the need for a new hire in place. Thus, the program changes were approved by the English Department, and I learned that it is a good use of time to visit your colleagues to both hear and put to rest these types of objections long before bringing them up for a vote at a department meeting.

At the next level, the Dean’s office objected to the new Advanced Topics course because of pressure from the administration to trim away unnecessary courses instead of adding new courses. I had to defend its necessity as a course, with Dr. Smith’s assistance. Part of our argument was that the course would be a place for faculty to teach courses based on the latest research in the field on a variety of topics; in addition, it could draw upon specialized research done for work on the dissertation, or it could be based on new knowledge and expertise gained by doing other projects on campus or for grants. Thus, I had to be prepared to make an argument for its inclusion based on the unique limitations and needs of our university.

At the next level up, one member from the Art Department on the college curriculum committee objected to the words “Document Design” in the Visual Rhetoric course. Since the Art Department teaches graphic design courses, this professor wanted to be clear that we were not duplicating this knowledge. As a result, I added a description that indicated students would be designing workplace documents, as opposed to more “artistic” types of design, in order to appease this objector.

Finally, the Educational Policy Committee wanted revisions to show my courses met the requirements for writing intensive courses. A review of the requirements revealed that I had to assign, grade, and return an essay early in the course in order to fulfill these requirements. I made this clear on the sample syllabi and schedules I had to submit, and the committee gave the final approval.

Getting the Word Out

Trying to attract students to new courses requires a great deal of advertisement and a great deal of explaining new terms such as “rhetoric” to them in ways that are engaging. However, I had several obstacles to getting the word out. New students could not locate the program on the department website, nor was it in the brochure for the department. Furthermore, it was not a part of the materials available for summer recruitment.

In response to my concerns about the program’s lack of visibility, my colleagues and chair were supportive. My chair asked me to write the text describing the program for the new department website and allowed me to sign up for the specialized training needed to update the website. She also asked me to write the text for a letter to go to first-year students who indicated interest in the program. I emphasized both the practical aspects of taking courses in the concentration or minor, such as how well the Professional and Technical Writing courses prepare students for jobs as well as the value of the internship, along with a description of how learning about persuasion empowers us. Finally, my chair encouraged me to send her text and pictures for some new slides in the orientation PowerPoint that is shown to all new students during orientation activities.

My colleagues responded to my pleas for help by encouraging their students to consider taking the courses in rhetoric. They let me put up posters (see Appendix 1) advertising the program and my courses on their doors and allowed me to describe the program to English majors during a required Literary Analysis course.{2} I was only given five minutes to share a description of the program, but in that time, I displayed the new Libguide for the concentration (a new Web 2.0 technology increasingly being used by libraries), named and briefly defined each course, and communicated the fact that I valued literary studies and found places of overlap between my field and literary studies. I emphasized the connection between rhetoric and literature, noting that students would be allowed to choose their own texts for analysis in the upcoming History of Rhetoric course. My hope was to build a bridge between the two disciplines. Thus, Jim Corder’s “Rhetoric and Literary Study: Some Lines of Inquiry” became required reading in my first rhetoric course.

Our efforts eventually paid off. We had come from humble beginnings. In the fall of 2007, the registrar’s office gave me a list of five students who were concentrating or minoring in the program. When I contacted them, I discovered three of the five had opted out of the program. However, in the spring of 2009, I had sixteen students enrolled in the same History of Rhetoric course that had run with only five students in the fall of 2006 and that failed to make in the fall of 2007. In the fall of 2009, the new Visual Rhetoric and Document Design course attracted twenty-one students, and in the spring of 2010, Rhetorical Criticism attracted sixteen students. Currently the program has twenty-two students either concentrating or minoring in the program. Four of those twenty-two graduated this spring, but the program is continuing to attract attention and has a healthy body of students committed to it.

Other Efforts to Increase Visibility

Reviving the program required more than posters and emails. Initially, with the permission of the chair, I designed a separate newsletter just for the program and sent it to the students. The newsletter explained the program, advertised the courses, defined rhetoric using multiple quotations from famous rhetoricians such as Aristotle, Burke, and Corder, and updated students on events.{3} Since the English Department’s website was waiting for revision and inclusion on the new Red Dot system (a new system for formatting websites that would standardize our “look”), I created a libguide for students to access from the library homepage.

Initially I enlisted the help of two interns who posted information on different major figures in rhetoric to the new libguide. However, I began to significantly revise the libguide as I conversed more with students. Over the following year, the libguide listed the new courses required in the concentration and minor, offered much more extended rationale for the program, and linked to master’s degree programs in Virginia. The rationale and a list of learning outcomes articulated on the site are listed in Appendix 2. The libguide also included information on current events associated with the program, offered specific job search advice and a list of career options, and gave advice to advisees that highlighted the fact that concentrating in Rhetoric and Professional Writing required only 120 hours for completing a Bachelor’s degree while competing programs required 124 and 136. The libguide saved me a great deal of time after it was built because students could quickly find answers to the questions so many of them had. It also gave the program visibility on the library’s homepage.

I also designed a personal website to be hosted on Longwood’s server. It made my interests and areas of expertise clear to the students. It also allowed new students to see me on a more individual and human level and increased the level of accessibility for them. Although I’m still not sure of the website’s impact, I still update it and make it available to the students.

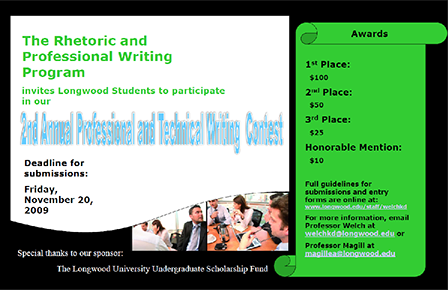

To increase the program’s visibility, two professional writing contests, funded by the Undergraduate Scholarship Fund, were run in the fall of 2008 and the fall of 2009. Participation was incredibly low, but the advertisement for the program through the flyer posted in 2008 and the poster in 2009 helped give even more visibility to the new program.{4} Additional opportunities for advertisement came through three Q&A events and a spring social. These gave students a chance to ask questions, look over textbooks, and get to know each other as well. In the spring of 2010, I held a social in my home to celebrate the four students graduating from the program and to allow the continuing students time to get to know each other. It was a success. This fall of 2010, I took advantage of a “Meet Your Major” night sponsored by Student Services and asked my new colleague to attend with handouts for the program (I had another campus event the same evening). Fifteen students came out to speak with her.

In addition to the online resources and campus activities, I took advantage of the opportunity to co-present with students at the Mountain Lake Leadership Retreat hosted by SEAL, a student leadership organization, which is held in Pembroke, Virginia over a weekend in November. Around 150 students come each year to spend the weekend together in the hotel where the movie “Dirty Dancing” was filmed. A keynote speaker kicks off the weekend on Friday night, and Saturday is spent in hands-on workshops led by students and faculty. The first year I went (fall 2008), several students signed up to work with me on the presentation, but only one student actually ended up going. However, some of the students who participated in the workshop enjoyed it so much they signed up for my classes after that. We presented on how to use professional writing to set up successful community service projects. The next year I went (fall 2009), I took several students with whom I had built relationships through the program, and we gave another workshop. Our presentation was called “How to Use Visual Rhetoric and Document Design to Establish Yourself as a Leader.” Both workshops reinforced solidarity with those already committed to the program and drew in new students.

Finally, as an ongoing activity, I request an updated list of students who have declared a concentration or minor in the program every semester and contact those students by email about upcoming courses and events. I invite them to ask me questions and make it clear that I am available. I regularly redesign the bulletin board in our building that is devoted to advertising the program. Although low-tech, I believe the two posters I created to advertise the Visual Rhetoric and Document Design course were a major factor in getting students interested in taking the course. One poster was an amalgamation of visuals and questions related to the study of visual rhetoric, i.e. “Who occupies a position of power?” The other poster was similar, but with a focus on the terms (emphasis, clarity, ethos, etc.) associated with document design. Both were multi-layered and incorporated a variety of materials, such as photos, copies of paintings, graphs, and so on. I set them up against a fabric backdrop for emphasis and contrast. The students seemed to enjoy looking at the posters, which were examples of the power of visual rhetoric, and several told me the questions I posted were provocative and got them interested in taking the course. I also make it clear that I am willing to help students find internships and to work with them myself if they choose to fulfill the requirement that way. And, perhaps most importantly, I regularly offer Professional Writing and Editing and Technical Writing fully online in the regular academic year and in the summer. The students appreciate the convenience of taking these courses online.

What I Would Change

If I could go back and do things differently, I would have done more to enlist the help and funding of the administration to request money for scholarships, participation in conferences, and related travel to conferences for myself and for students. Anyone hired to build a program should be provided with some funds for developing that program, and getting the attention of the administration early in the process might have resulted in more opportunities than I could imagine on my own. The added burdens of advertising and building the program on my own have been incredibly time-consuming. Because of budget constraints, none of the rewards have been financial, and I’ve even had to cover the cost of some of the posters and social events out of my personal funds because the department did not have much of a budget. If I were to do this over again, I would request at least a small amount for start up funds in building the program. However, the payoff is that the program has effectively been rekindled and will continue to grow.

I would also collaborate with another colleague in order to co-teach a course. While I have worked with my colleagues to develop the program, this fall, I am teaching the Advanced Topics Course and focusing on Women’s Rhetorics. I only have ten students, and I believe that I would have attracted more if I had teamed up with one of the two literature professors teaching women’s literature classes this summer. It would be interesting to co-teach a course that clearly draws upon the strengths of a literature course and its analytical point of view and a rhetoric course and its different concerns and tools of analyses.

Future Goals

The Rhetoric and Professional Writing Concentration and Minor will continue far into the future now that the program has begun to attract students. This fall, a new colleague joined me, Heather Lettner-Rust. The courses are now adequately staffed, and as we grow the program, we are already voicing a hope we can add a third faculty member to the department from our field.

This fall of 2010, the new Rhetoric and Professional Writing Club was approved by the Student Government Association. The club will give us access to money for speakers, and it will give us an opportunity to do a community service project every year. It will also take some of the burden of advertising the program off of me. Club members can produce a newsletter and create advertisements, as well as speak on behalf of the program to prospective new students.

Because of the success with the undergraduate program, my new colleague and I will be discussing plans for a new master’s program in Rhetoric and Professional Writing in the coming academic year. I’ve been given a course release for 2011-2012 in order to structure a program, and I am now researching other programs to see what I can use as a pattern for success in ours. I do hope to build on the clearly defined goals already set, as well as maintain a focus on rhetoric as well as professional and technical writing.

In order to continue to evaluate the program and set future goals, I sent out a survey this spring to get some feedback from the students who would be graduating. Here are two responses that reveal how the connections made in the coursework between rhetoric and professional writing have been appreciated by the students:

Response #1:

“I think the program incorporated a lot of interesting real world application type activities. This is helpful for me personally, because at least I know I can take my skills into the world and when I am asked to complete a proposal, draft a memo, or write a letter I have the experience needed to complete the task effectively. I think it would be interesting if more was taught about the opportunities that a professional writing degree/minor can offer in the professional world. I really liked the activity we did in visual rhetoric and document design when the woman from the LCVA came and discussed the path she took from teaching, to working at Monticello to working at the LCVA. It really showed the types of opportunities available, and I think more could be taught about how to enter this field and what to expect once there. Overall, I really believe I benefited from choosing this as my minor. I am now a step ahead of my peers in Communication Studies because not only am I an expert at verbal communication, but I can also make arguments and achieve purpose through writing.”

Response #2:

“Overall, I think Rhetoric was the best path for me to take. I enjoy writing and the Rhetoric concentration has molded my writing into something different, yet also better. I'm more confident in my writing because I understand what it truly means to use persuasive language…because after all, that's what rhetoric is.”

Ultimately, reinventing and reviving the program in Rhetoric and Professional Writing has required a great deal of work, but all of that effort has been worth it. Focusing on rhetoric has allowed students to explore effective, purposeful persuasion in conjunction with a focus on practical writing skills. Understanding the principles of rhetoric and exploring the contexts of documents are important for preparing students for thoughtful, conscious action in the working world. Finally, building a program based on a set of clearly outlined program goals that uses rhetoric as a means for enriching courses in writing has paid off in terms of student interest and my fulfillment as one who has the privilege of teaching these courses and working with these students.

Appendices

Appendix 1: Advertising Posters

Thumbnail versions of three posters used to advertise the program are below. Larger images, text descriptions, and other formats are also available.

Poster for Rhetorical Criticism Course

Poster for Professional & Technical Writing Contest

Poster for Rhetoric & Professional Writing Program

Appendix 2: Rationale and Outcomes from Libguide

From the Rhetoric and Professional Writing Libguide at http://libguides.longwood.edu/rhetoric:

Rationale:

Why choose Rhetoric and Professional Writing?

As leading technical writing textbook author Mike Markel quotes, “A study of more than 100 large American corporations, which together employ some 8 million people, suggests that writing is a more important skill for today’s professionals than it has ever been,” according to a 2004 study by the College Board (3). Writing is needed just to get hired. “86% of companies surveyed” would probably not hire an applicant whose materials are poorly written (3). 80% of companies in the “service, finance, insurance and real-estate industries assess applicants’ writing during the hiring process” and take these skills into account when making decisions about promotion (3). These claims are corroborated by a recent article by the National Commission on Writing.

"’Writing is both a 'marker' of high-skill, high-wage, professional work and a 'gatekeeper' with clear equity implications,’ said Bob Kerrey, president of New School University in New York and chair of the Commission. ‘People unable to express themselves clearly in writing limit their opportunities for professional, salaried employment,’ he said” (National Commission on Writing).

Additionally, Markel points out that 40% of the cost of “managing business and government transactions is due to poor communication” (3). “Eight major companies…put communication skills at the top of the list of traits they look for in employees” and 90% of “more than 800 business school graduates say that their writing skills have helped them advance more quickly” (3). The National Commission on Writing claims that their report on writing in the workplace reveals: “More than 40% of responding firms offer or require training for salaried employees with writing deficiencies. ‘We're likely to send out 200—300 people annually for skills upgrade courses like 'business writing' or 'technical writing,' said one respondent.”

Markel writes that 50% of companies in the report on workplace writing regularly require employees to write reports, memos, and letters, about 100% use email, and over 80% use powerpoint regularly (3).

Works Cited: Markel, Mike. Technical Communication. 9th ed. Bedford St. Martin’s: New York, 2010.

“National Commission on Writing, Writing Skills Necessary for Employment, Says Big Business: Writing Can be a Ticket to Professional Jobs, Says Blue-Ribbon Group.” Writing Commission. (Sept. 14). Web. http://www.writingcommission.org/pr/writing_for_employ.html

Some learning objectives for the Rhetoric and Professional Writing Program, to be covered in one or more courses, include:

Students will learn to analyze professional cultures, social contexts, and audiences to determine how they shape the various purposes and forms of writing, such as persuasion, organizational communication, and public discourse.

Students will learn to develop and understand various strategies for planning, researching, drafting, revising, and editing documents that respond effectively and ethically to professional situations and audiences.

Students will learn to understand and use various research methods (annotated bibliographies, use of library databases, interviews of professionals or other types of real-world research) to produce professional documents and/or analytical research papers.

Students will learn to develop strategies for using and adapting various communication technologies (Word, Excel, PowerPoint, web design, etc.) to manage projects and produce informative and usable professional documents.

Students will learn to argue with visual data, and to understand and implement various principles of format, layout, and design of professional documents that meet multiple user and reader needs.

Students will learn to use rhetoric as means of analyzing a document, situation, or other artifact.

Students will learn to use knowledge about rhetoric as a way to successfully and ethically practice persuasion. In other words, students will come to understand and connect the theories learned to the practical application of those theories in real-world contexts.

Students will learn to hone critical thinking skills through summary, analysis, response, critical inquiry, synthesis of research with their ideas, etc.

Notes

- In conjunction with the CAFÉ workshop committee, I organized a full day workshop on WAC at Longwood University on October 2, 2010. Only a small number of faculty attended, but the response was positive, and all attendees expressed the opinion that the information was much needed and useful. (Return to text.)

- In order to encourage students to enroll in History of Rhetoric, I sent out two emails to the department, and I sent a description to Dr. Smith for inclusion in the English Department newsletter that explained that History of Rhetoric was not the kind of history course with dates to memorize, but the kind of history course that explored the recursive development of rhetorical theories and frameworks for analysis as they emerged over the centuries. I explained to students that the rhetorical analysis required for the major paper could be done on any text—poetry, fiction, non-fiction—of their choice. By showing that I valued literature, students who were not a part of the concentration or minor felt comfortable trying out the course. (Return to text.)

- After trying unsuccessfully to persuade the students to take over the newsletter, I finally abandoned it due to my heavy workload. In the Spring of 2011, a student has requested the opportunity to revive it, so we’ll bring it back in digital form. (Return to text.)

- The contest poster is included in Appendix 1. I no longer have the flyer for the first contest, but it was simple to create using a Word 2007 template. (Return to text.)

Works Cited

“2007-2008 Catalog.” Longwood University Website. 2010. Web. http://www.longwood.edu/academicaffairs/21836.htm.

Bizzell, Patricia and Bruce Herzberg. The Rhetorical Tradition: Readings from Classical Times to the Present. 2nd ed. Boston: Bedford Books of St. Martin's Press, 2001. Print.

Burnsed, Brian. “Degrees are Great, but Internships Make a Difference.” U.S. News and World Report. April 15, 2010. Web. http://www.usnews.com/education/best-graduate-schools/articles/2010/04/15/when-a-degree-isnt-enough.html.

Corder, Jim. “Rhetoric and Literary Study: Some Lines of Inquiry.” College Composition and Communication 32.1 (1981): 13-20. Print.

Dragga, Sam. “Positioning Programs in Professional and Technical Communication: Guest Editor’s Introduction.” Technical Communication Quarterly. 19.3 (Jul-Sep 2010): 221-224. Print.

Katz, Steven B. "The Ethics of Expediency: Classical Rhetoric, Technology, and the Holocaust." College English 54.3 (March 1992): 255–75. Print.

“About Longwood.” Longwood University Website. 2010. Web. http://www.longwood.edu/about.htm.

“Mass Media.” Longwood University Website. 2010. Web. http://www.longwood.edu/commstudiestheatre/17306.htm.

Miller, Carolyn. “Kairos in the Rhetoric of Science.” A Rhetoric of Doing: Essays on Written Discourse in Honor of James L. Kinneavy. Ed. Stephen P. Witte, Neil Nakadate, and Roger D. Cherry. Carbondale: Southern Illinois UP, 1992. 310–327. Print.

———. “A Humanistic Rationale for Technical Writing.” College English 40 (Feb. 1979): 610–617. Print.

Potts, Liza. "Using Actor Network Theory to Trace and Improve Multimodal Communication Design." Technical Communication Quarterly. 18.3. (July-Sept. 2009): 281-301. Print.

Rentz, Kathryn, Mary Beth Debs, and Lisa Meloncon. “Getting an Invitation to the English Table and Whether or Not to Accept It.” Technical Communication Quarterly. 19.3 (Jul-Sep 2010): 281-299. Print.

Selfe, Richard J., and Cynthia L. Selfe. "Convince Me!" Valuing Multimodal Literacies and Composing Public Service Announcements.” Theory Into Practice. 47.2 (April 2008): 83-92. Print.

Tyler, Lisa. "Ecological Disaster and Rhetorical Response: Exxon's Communications in the Wake of the Valdez Spill." Journal of Business and Technical Communication 6 (April 1992): 149–71. Print.

Vasudevan, Lalitha, Katherine Schultz, and Jennifer Bateman. “Rethinking Composing in a Digital Age: Authoring Literate Identities Through Multimodal Storytelling.” Written Communication. 27.4 (October 2010): 442-468. Print.

Winsor, D. "The Construction of Knowledge in Organizations: Asking the Right Questions about the Challenger." Journal of Business and Technical Communication 4 (1990): 7–20. Print.

“Rekindling Longwood University’s Writing Minor” from Composition Forum 23 (Spring 2011)

Online at: http://compositionforum.com/issue/23/longwood.php

© Copyright 2011 Kristen Dayle Welch.

Licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-Share Alike License.

Return to Composition Forum 23 table of contents.